Imagining Modernity in the Uganda Prisons Service, 1945-1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part of a Former Cattle Ranching Area, Land There Was Gazetted by the Ugandan Government for Use by Refugees in 1990

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 32 UNHCR’s withdrawal from Kiryandongo: anatomy of a handover Tania Kaiser Consultant UNHCR CP 2500 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] October 2000 These working papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online at <http://www.unhcr.org/epau>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction The Kiryandongo settlement for Sudanese refugees is located in the north-eastern corner of Uganda’s Masindi district. Part of a former cattle ranching area, land there was gazetted by the Ugandan government for use by refugees in 1990. The first transfers of refugees took place shortly afterwards, and the settlement is now well established, with land divided into plots on which people have built houses and have cultivated crops on a small scale. Anthropological field research (towards a D.Phil. in anthropology, Oxford University) was conducted in the settlement from October 1996 to March 1997 and between June and November 1997. During the course of the fieldwork UNHCR was involved in a definitive process whereby it sought to “hand over” responsibility for the settlement at Kiryandongo to the Ugandan government, arguing that the refugees were approaching self-sufficiency and that it was time for them to be absorbed completely into local government structures. The Ugandan government was reluctant to accept this new role, and the refugees expressed their disbelief and feelings of betrayal at the move. -

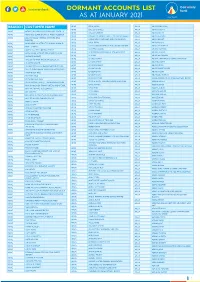

1612517024List of Dormant Accounts.Pdf

DORMANT ACCOUNTS LIST AS AT JANUARY 2021 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME APAC OKAE JASPER ARUA ABIRIGA ABUNASA APAC OKELLO CHARLES ARUA ABIRIGA AGATA APAC ACHOLI INN BMU CO.OPERATIVE SOCIETY APAC OKELLO ERIAKIM ARUA ABIRIGA JOHN APAC ADONGO EUNICE KAY ITF ACEN REBECCA . APAC OKELLO PATRICK IN TRUST FOR OGORO ISAIAH . ARUA ABIRU BEATRICE APAC ADUKU ROAD VEHICLE OWNERS AND OKIBA NELSON GEORGE AND OMODI JAMES . ABIRU KNIGHT DRIVERS APAC ARUA OKOL DENIS ABIYO BOSCO APAC AKAKI BENSON INTRUST FOR AKAKI RONALD . APAC ARUA OKONO DAUDI INTRUST FOR OKONO LAKANA . ABRAHAM WAFULA APAC AKELLO ANNA APAC ARUA OKWERA LAKANA ABUDALLA MUSA APAC AKETO YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT APAC ARUA OLELPEK PRIMARY SCHOOL PTA ACCOUNT ABUKO ONGUA APAC AKOL SARAH IN TRUST FOR AYANG PIUS JOB . APAC ARUA OLIK RAY ABUKUAM IBRAHIM APAC AKONGO HARRIET APAC ARUA OLOBO TONNY ABUMA STEPHEN ITO ASIBAZU PATIENCE . APAC AKULLU KEVIN IN TRUST OF OLAL SILAS . APAC ARUA OMARA CHRIST ABUME JOSEPH APAC ALABA ROZOLINE APAC ARUA OMARA RONALD ABURA ISMAIL APAC ALFRED OMARA I.T.F GERALD EBONG OMARA . APAC ARUA OMING LAMEX ABURE CHRISTOPHER APAC ALUPO CHRISTINE IN TRUST FOR ELOYU JOVIN . APAC ARUA ONGOM JIMMY ABURE YASSIN APAC AMONG BEATRICE APAC ARUA ONGOM SILVIA ABUTALIBU AYIMANI APAC ANAM PATRICK APAC ARUA ONONO SIMON ACABE WANDI POULTRY DEVELPMENT GROUP APAC ANYANGO BEATRASE APAC ARUA ONOTE IRWOT VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ACEMA ASSAFU APAC ANYANZO MICHEAL ITF TIZA BRENDA EVELYN . APAC ARUA OPIO JASPHER ACEMA DAVID APAC APAC BODABODA TRANSPORTERS AND SPECIAL APAC ARUA OPIO MARY ACEMA ZUBEIR APAC APALIKA FARMERS ASSOCIATION APAC ARUA OPIO RIGAN ACHEMA ALAHAI APAC APILI JUDITH APAC ARUA OPIO SAM ACHIDRI RASULU APAC APIO BENA IN TRUST OF ODUR JONAN AKOC . -

Oral Arguments

ORAL ARGUMENTS MINUTES OF THE PUBLIC SI'ITINGS held or the Peace Palace, The Hague, from 4 ro 26 Jurre 1973 FlRST PUBLIC SITTING (4 VI 73, 3 p.m.) Present: Presidenr LACHS;Vice-Presideitf AMMOUN;J~~dges FORSTER, GROS, BENGZON,PETRÉN, ONYEAMA, IGNACIO-PINTO, DE CASTRO,MOROZOV, JIMÉNEZ DE ARÉCHAGA,SIR Humphrey WALDOCK,NAGEKORA SINGE, RUDA; Ji~dge ad hoc Sir Muhammad ZAFRULLAKHAN; Regisrrar AOUARONE. Also preseitt: Far tlre Covernnlenr of Pokisran: H.E. Mr. J. G. Kharas, Ambassadorof Pakistan to IheNetherlands, as Agent; Mr. S. T. Joshua, Secretary of Embassy, as Deputy-Agent; Mr. Yahya Bakhtiar, Attorney-General of Pakistan. as Clrief Counsel; Mr. Zahid Said, Deputy Legal Adviser, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Govern- ment of Pakistan, as Cowtsel. PAKISTANI PRISONERS OF WAR OPENING OF THE ORAL PROCEEDLNGS The PRESIDENT: The Court meets today to consider the request for the indication of interim measures of protection, under Article 41 of the Statute of the Court and Article 66 of the 1972 Rules of Court, filed by the Government of Pakistan on II May 1973, in the case concerning the Trial of Pakistani Prisoners of War, brought by Pakistan against India. The proceedings in this case were begun by an Application by the Govern- ment of Pakistan, filed in the Registry of the Court on 11 May 1973'. The Application founds the jurisdiction of the Court on Article IX of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948, generally known as "the~ ~ Genocide~ Convention". -

Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:511 Jinja District for FY 2018/19. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Jinja District Date: 30/10/2018 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 5,039,582 2,983,815 59% Discretionary Government Transfers 4,063,070 1,063,611 26% Conditional Government Transfers 35,757,925 9,198,562 26% Other Government Transfers 2,554,377 432,806 17% Donor Funding 564,000 0 0% Total Revenues shares 47,978,954 13,678,794 29% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 183,102 22,472 21,722 12% 12% 97% Internal Audit 132,830 32,942 27,502 25% 21% 83% Administration 6,994,221 1,589,106 1,385,807 23% 20% 87% Finance 1,399,200 320,632 310,572 23% 22% 97% Statutory Bodies 995,388 234,790 160,795 24% 16% 68% Production and Marketing 1,435,191 -

“The Life and Contribution of the Late Benedicto K. M. Kiwanuka to the Political History of Uganda”

“The Life and Contribution of the Late Benedicto K. M. Kiwanuka to the Political History of Uganda” By Paul K. Ssemogerere, Former Deputy Prime Minister & Retired President of the Democratic Party A Lecture in Memory of Benedicto Kiwanuka Organized by the Foundation for African Development and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung on 13th October 2015, Hotel Africana 1. Introduction I believe I am speaking for all present, when I express sincere appreciation to the leadership of the Foundation for African Development (FAD), who, in collaboration with the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) of Germany, instituted this series of Annual Memorial Lectures/Dialogues in happy memory of someone who lived and worked under great difficulties but, guided by noble principles, and propelled by sustained personal endeavor to lead in order to serve, rose to great heights, and eventually leaving his star shining brightly for all of us long after his awful extra- judicial execution – an execution orchestrated by fellow-men held captive by envy and personal insecurity. I welcome today’s main presentation for the Dialogue on “What needs to be done to avert the risk of election violence before, during and after the 2016 General Elections in Uganda”, for three main reasons: • First, because anxiety about the likelihood of violence breaking out with disastrous consequences is well founded; there are simply too many things wrong about the forthcoming election while, at the same time, there is, so far, an apparent lack of genuine interest to address them seriously and objectively -

Bujagali Final Report

INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL COMPLIANCE REVIEW REPORT ON THE BUJAGALI HYDROPOWER AND INTERCONNECTION PROJECTS June 20, 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The IRM Compliance Review Panel could not have undertaken and completed this report without the generous assistance of many people in Uganda and at the African Development Bank. It wishes to express its appreciation to all of them for their cooperation and support during the compliance review of the Bujagali Hydropower and Interconnection projects. The Panel thanks the Requesters and the many individuals from civil society and the communities that it met in the Project areas and in Kampala for their assistance. It also appreciates the willingness of the representatives of the Government of Uganda and the projects’ sponsors to meet with the Panel and provide it with information during its visit to Uganda. The Panel acknowledges all the help provided by the Resident Representative of the African Development Bank in Uganda and his staff and the willing cooperation it has received from the Bank’s Management and staff in Tunis. The Panel appreciates the generous cooperation of the World Bank Inspection Panel which conducted its own review of the “UGANDA: Private Power Generation Project”. The Compliance Review Panel and the World Bank Inspection Panel coordinated their field investigations of the Bujagali projects and shared consultants and technical information during this investigation in order to enhance the efficiency and cost effectiveness of each of their investigations. While this collaboration between the Panel and the World Bank Inspection Panel worked to the mutual benefit of both parties, each Panel focused its compliance review on its own Bank’s policies and procedures and each Panel has made its own independent judgments about the compliance of its Management and staff with its Bank’s policies and procedures. -

Assessment Form

Local Government Performance Assessment Jinja District (Vote Code: 511) Assessment Scores Accountability Requirements % Crosscutting Performance Measures 81% Educational Performance Measures 82% Health Performance Measures 79% Water & Environment Performance Measures 89% 511 Accountability Requirements 2019 Jinja District No. Summary of requirements Definition of compliance Compliance justification Compliant? Annual performance contract 1 Yes LG has submitted an annual performance contract of the • From MoFPED’s The Annual Performance forthcoming year by June 30 on the basis of the PFMAA inventory/schedule of LG Contract of the forth coming year and LG Budget guidelines for the coming financial year. submissions of performance was submitted on 8th July 2019 contracts, check dates of within the adjusted submission submission and issuance of date of 31st August, 2019 receipts and: o If LG submitted before or by due date, then state ‘compliant’ o If LG had not submitted or submitted later than the due date, state ‘non- compliant’ • From the Uganda budget website: www.budget.go.ug, check and compare recorded date therein with date of LG submission to confirm. Supporting Documents for the Budget required as per the PFMA are submitted and available 2 Yes LG has submitted a Budget that includes a Procurement • From MoFPED’s inventory of The LG submitted the approved Plan for the forthcoming FY by 30th June (LG PPDA LG budget submissions, check Budget Estimates that included a Regulations, 2006). whether: Procurement Plan for the FY 2019/20 on 8 thJuly, 2019 thus o The LG budget is accompanied being within the adjusted time by a Procurement Plan or not. -

Profiling Problem Projects Uganda's Bujagali

Profiling Problem Projects Uganda’s Bujagali Dam: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare By Lori Pottinger, September 2000 International Rivers Network Introduction Uganda is one of the world's poorest IFC sponsorship of the dam project is countries, and its poverty is a key reason expected to demonstrate the viability of why less than 5% of the population has hydropower on the Nile in Uganda, which access to electricity. A World Bank study could open up the river for sale to the states, “No more than 7% of the total highest bidder in a plan to build as many as population [in Uganda] can afford 6 dams and export the power. Project unsubsidized electricity… It is unrealistic to documents claim this dam will be relatively think that more than a fraction of the rural benign, but there is inadequate information population could be reached by a about cumulative impacts (Bujagali Dam conventional, extend-the-grid approach. A would be the third dam on one short stretch more promising course is to rely instead on of the river; the two previous dams did not 'alternative,' 'non-conventional' approaches have environmental impact assessments). to electrification."1 And yet, the IFC is now evaluating a 250 megawatt hydropower Finally, this case highlights a potential project,2 the Bujagali Dam on Uganda’s conflict of interest between the Bank's White Nile, whose electricity would be out public and private lending operations. The of reach to the vast majority of Uganda’s World Bank’s public sector arm is citizens. The project will almost double pressuring the Ugandan government to Uganda’s grid-based electricity supply, at a restructure its energy sector to ensure the time when energy experts are questioning smooth functioning of the private sector. -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

Water Safety Plans for Utilities in Developing Countries - a Case Study from Kampala, Uganda

Water Safety Plans for Utilities in Developing Countries - A case study from Kampala, Uganda Sam Godfrey, Charles Niwagaba, Guy Howard, Sarah Tibatemwa 1 Acknowledgements The editor would like to thank the following for their valuable contribution to this publication: Frank Kizito, Geographical Information Section (GIS), ONDEO Services, Kampala, Uganda Christopher Kanyesigye, Quality Control Manager National Water and Sewerage (NWSC), Kampala, Uganda Alex Gisagara, Planning and Capital Development Manager, National Water and Sewerage (NWSC), Kampala, Uganda Godfrey Arwata, Analyst Microbiology National Water and Sewerage (NWSC), Kampala, Uganda Maimuna Nalubega, Public Health and Environmental Engineering Laboratory, Department of Civil Engineering, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Rukia Haruna, Public Health and Environmental Engineering Laboratory, Department of Civil Engineering, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Steve Pedley, Robens Centre for Public and Environmental Health, University of Surrey, UK Kali Johal, Robens Centre for Public and Environmental Health, University of Surrey, UK Roger Few, Faculty of the Built Environment, South Bank University, London, UK The photograph on the front cover shows a water supply main crossing a low lying hazardous area in Kampala, Uganda (Source: Sam Godfrey) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS: WATER SAFETY PLANS FOR UTILITIES IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES.1 - A CASE STUDY FROM KAMPALA, UGANDA..................................................1 Acknowledgements.................................................................................................2 -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

The History of Syphilis in Uganda

Bull. Org. mond. Santeh 1956, 15, 1041-1055 Bull. Wld Hith Org. THE HISTORY OF SYPHILIS IN UGANDA J. N. P. DAVIES, M.D., Ch.B., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. Professor of Pathology, Makerere College Medical School, Kampala, Uganda SYNOPSIS The circumstances of an alleged first outbreak of syphilis in Uganda in 1897 are examined and attention is drawn to certain features which render possible alternative explanations of the history of syphilis in that country. It is suggested that an endemic form of syphilis was an old disease of southern Uganda and that protective infantile inoculation was practised. The country came under the observation of European clinicians at a time when endemic syphilis was being replaced by true venereal syphilis. This process has now been completed, endemic syphilis has disappeared, and venereal syphilis is now widespread and a more serious problem than ever. This theory explains the observations of other writers and reconciles the apparent discrepancies between various reports. Until comparatively recent times the country now known as Uganda was cut off from the rest of the world. The Nile swamps to the north, the impenetrable Congo forest to the west, the mountains and the upland plateaux with the warrior Masai to the east, and the other immense difficul- ties of African travel, had protected the country from intrusion. In the southern lacustrine areas there had developed the remarkable indigenous kingdoms of Bunyoro and Buganda. These became conscious of the larger outside world about 1850, when a Baluch soldier from Zanzibar reached the court of the King of Buganda, the Kabaka Suna.