Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

DIALOGUE PO Box 1094 Farmington, UT 84025 electronic service requested DIALOGUE 52.3 fall 2019 52.3 DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought EDITORS DIALOGUE EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT a journal of mormon thought ASSOCIATE EDITOR David W. Scott, Lehi, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT FICTION Jennifer Quist, Edmonton, Canada POETRY Elizabeth C. Garcia, Atlanta, GA IN THE NEXT ISSUE REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan Papers from the 2019 Mormon Scholars in the INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS Humanities conference: “Ecologies” HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT A sermon by Roger Terry FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT Karen Moloney’s “Singing in Harmony, Stitching in Time” ART Andi Pitcher Davis, Orem, UT BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF Join our DIALOGUE! BUSINESS MANAGER Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT PUBLISHER Jenny Webb, Woodinville, WA Find us on Facebook at Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought COPY EDITORS Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI Follow us on Twitter @DialogueJournal Jared Gillins, Washington DC PRINT SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS EDITORIAL BOARD ONE-TIME DONATION: 1 year (4 issues) $60 | 3 years (12 issues) $180 Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT Becky Reid Linford, Leesburg, VA Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA RECURRING DONATION: Verlyne Christensen, Calgary, AB Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA $10/month Subscriber: Receive four print issues annually and our Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Taylor Petrey, Kalamazoo, MI Subscriber-only digital newsletter Ignacio M. -

LDS (Mormon) Temples World Map

LDS (Mormon) Temples World Map 155 operating temples · 14 temples under construction · 8 announced temples TEMPLES GOOGLE EARTH (KML) TEMPLES GOOGLE MAP TEMPLES HANDOUT (PDF) HIGH-RES TEMPLES MAP (GIF) Africa: 7 temples United States: 81 temples Alabama: 1 temple Aba Nigeria Temple Birmingham Alabama Temple † Abidjan Ivory Coast Temple Alaska: 1 temple Accra Ghana Temple Anchorage Alaska Temple † Durban South Africa Temple Arizona: 6 temples † Harare Zimbabwe Temple Gila Valley Arizona Temple, The Johannesburg South Africa Temple Gilbert Arizona Temple Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Mesa Arizona Temple † Temple Phoenix Arizona Temple Snowflake Arizona Temple Asia: 10 temples Tucson Arizona Temple† Bangkok Thailand Temple† California: 7 temples Cebu City Philippines Temple Fresno California Temple Fukuoka Japan Temple Los Angeles California Temple Hong Kong China Temple Newport Beach California Temple Manila Philippines Temple Oakland California Temple Sapporo Japan Temple Redlands California Temple Seoul Korea Temple Sacramento California Temple Taipei Taiwan Temple San Diego California Temple Tokyo Japan Temple Colorado: 2 temples http://www.ldschurchtemples.com/maps/ LDS (Mormon) Temples World Map Urdaneta Philippines Temple† Denver Colorado Temple Fort Collins Colorado Temple Europe: 14 temples Connecticut: 1 temple Hartford Connecticut Temple Bern Switzerland Temple Florida: 2 temples Copenhagen Denmark Temple Fort Lauderdale Florida Temple ‡ Frankfurt Germany Temple Orlando Florida Temple Freiberg Germany Temple Georgia: -

DIALOGUE DIALOGUE PO Box 381209 Cambridge, MA 02238 Electronic Service Requested

DIALOGUE DIALOGUE PO Box 381209 Cambridge, MA 02238 electronic service requested DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought 49.4 winter 2016 49.4 EDITORS EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT ASSOCIATE EDITOR David W. Scott, Lehi, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT DIALOGUE FICTION Julie Nichols, Orem, UT POETRY Darlene Young, South Jordan, UT a journal of mormon thought REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand Carter Charles, Bordeaux, France POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT ART Andrea Davis, Orem, UT IN THE NEXT ISSUE Brad Kramer, Murray, UT Brad Cook, “Pre-Mortality in Mystical Islam” BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF BUSINESS MANAGER Mariya Manzhos, Cambridge, MA PRODUCTION MANAGER Jenny Webb, Huntsville, AL Allen Hansen & Walker Wright, “Worship through COPY EDITORS Sarah Moore, Madison, AL Corporeality in Hasidism and Mormonism” Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI INTERNS Stocktcon Carter, Provo, UT Nathan Tucker, Provo, UT Fiction from William Morris Geoff Griffin, Provo, UT Christian D. Van Dyke, Provo, UT Fiction from R. A. Christmas Ellen Draper, Provo, UT EDITORIAL BOARD Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Thomas F. Rogers, Bountiful, UT Ignacio M. Garcia, Provo, UT Mathew Schmalz, Worcester, MA Join our DIALOGUE! Brian M. Hauglid, Spanish Fork, UT David W. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Missionary Training Centers Sister Bingham at New Missionary Training Missionaries

Missionary Training Centers Sister Bingham at new missionary training missionaries. It includes two new United Nations center in Accra, Ghana, and an buildings on a five-building campus, A expanded missionary training located adjacent to the Philippines Area peaking during a faith-based center in Provo, Utah, USA, demon- offices and across the street from the Spanel discussion about refugee strate the continuing importance of Manila Philippines Temple. Since the integration at the United Nations in missionary service. Philippines MTC opened in 1983, it has New York City on April 13, 2017, The recently finished Ghana MTC, served missionaries from, or going to, Relief Society General President next to the Accra Ghana Temple, 60 nations. Jean B. Bingham expressed hope accommodates 320 missionaries and The expansion at the Provo MTC that faith-based organizations “will has room to grow. The larger facility includes two new six-story buildings all work together through small and accommodates missionaries leaving with 200 new classrooms, more than simple means to accomplish extraor- from west and southeast Africa, as well 100 practice teaching rooms, and 13 dinary things.” as missionaries from around the world computer labs where missionaries During the annual “Focus on who have been called to serve in Africa. receive training before they are sent to Faith” briefing, Sister Bingham The new buildings make it easier for their assigned areas around the world. discussed the Church’s humanitarian missionaries to learn in their native The Provo MTC has the capacity to efforts with refugees and expressed language—English or French—and train as many as 3,700 young men, sincere appreciation to all who are learn the language and culture of the young women, and senior missionaries engaged in the “challenging but area where they have been assigned at a time. -

APPLICATION for GRANTS UNDER the National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180115 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12659873 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180115 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (GEPA_Section_427_IMCLAS1024915422) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e17 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e18 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e19 Attachment - 1 (IMCLAS_Abstract20181024915421) e20 9. Project Narrative Form e21 Attachment - 1 (IMCLAS_Narrative_20181024915424) e22 10. Other Narrative Form e82 Attachment - 1 (FY_2018_Profile_Form_IMCLAS1024915425) e83 Attachment - 2 (IMCLAS_Table_Of_Contents_LAS1024915426) e84 Attachment - 3 (IMCLAS_Acronyms_List_20181024915427) e85 Attachment - 4 (IMCLAS_Diverse_Perspectives_and_National_Need_Descriptions1024915428) e87 Attachment - 5 (Appendix_1_IMCLAS_Course_List1024915429) e91 Attachment - 6 (Appendix_2_IMCLAS_Faculty_CVs1024915430) e118 Attachment - 7 e225 (Appendix_3_IMCLAS_Position_Description_for_Positions_to_be_Filled_and_Paid_from_the_Grant1024915431) Attachment - 8 (Appendix_4_IMCLAS_Letters_of_Support1024915436) e226 Attachment - 9 (Appendix_5_IMCLAS_PMF_20181024915437) e232 11. Budget Narrative -

Luna Lindsey Sample Chapters

Recovering Agency: Lifting the Veil of Mormon Mind Control by LUNA LINDSEY Recovering Agency: Lifting the Veil of Mormon Mind Control Copyright ©2013-2014 by Luna Flesher Lindsey Internal Graphics ©2014 by Luna Flesher Lindsey Cover Art ©2014 by Ana Cruz All rights reserved. This publication is protected under the US Copyright Act of 1976 and all other applicable international, federal, state and local laws. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, professional works, or reviews. www.lunalindsey.com ISBN-10: 1489595937 ISBN-13: 978-1489595935 First digital & print publication: July 2014 iv RECOVERING AGENCY Table of Contents FOREWORD' VIII' PART%1:%IN%THE%BEGINNING% ' IT'STARTED'IN'A'GARDEN…' 2' Free$Will$vs.$Determinism$ 3' Exit$Story$ 5' The$Illusion$of$Choice$ 9' WHAT'IS'MIND'CONTROL?' 13' What$is$a$Cult?$ 16' Myths$of$Cults$&$MinD$Control$ 17' ALL'IS'NOT'WELL'IN'ZION' 21' Is$Mormonism$A$DanGer$To$Society?$ 22' Why$ShoulD$We$Mourn$Or$Think$Our$Lot$Is$HarD?$ 26' Self<esteem' ' Square'Peg,'Round'Hole'Syndrome' ' Guilt'&'Shame' ' Depression,'Eating'Disorders,'&'Suicide' ' Codependency'&'Passive<Aggressive'Culture' ' Material'Loss' ' DON’T'JUST'GET'OVER'IT—RECOVER!' 36' Though$harD$to$you$this$journey$may$appear…$ 40' Born$UnDer$the$Covenant$ 41' We$Then$Are$Free$From$Toil$anD$Sorrow,$Too…$ 43' SLIPPERY'SOURCES' 45' Truth$Is$Eternal$$(And$Verifiable)$ 45' Truth$Is$Eternal$$(Depends$on$Who$You$Ask)$ 46' -

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

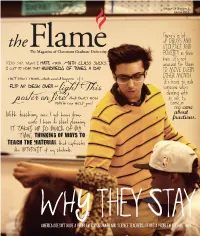

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

The Holy Priesthood, the Holy Ghost, and the Holy Community

THE HOLY PRIESTHOOD, THE HOLY GHOST, AND THE HOLY COMMUNITY Benjamin Keogh In response to the question “How can a spirit be a member of the godhead?” Joseph Fielding Smith wrote, “we should have no time to enter into speculation in relation to the Holy Ghost,” suggesting that we “leave a matter which in no way concerns us alone.”1 Perhaps because of this, the Holy Ghost has become one of the “most taboo and hence least studied”2 subjects in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Nevertheless, here I will explore the Holy Ghost’s purview, in its particular relation to priesthood. It may prove most useful to begin A version of this essay was given at the 2015 Summer Seminar on Mormon Culture. I would like to express thanks to Terryl and Fiona Givens and my fellow seminarians for their input and assistance. 1. Joseph Fielding Smith, “How Can a Spirit be a Member of the Godhead?,” in Answers to Gospel Questions, vol. 2 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1958), 145. Read in context, this suggestion to “leave the matter alone” may have more to do with speculation as to the Holy Ghost’s origin and destiny. 2. Vern G. Swanson, “The Development of the Concept of a Holy Ghost in Mormon Thought,” in Line Upon Line: Essays on Mormon Doctrine, edited by Gary James Bergera (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989), 89–101. Indeed, it appears that the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University holds only six LDS books on the subject: Oscar W. -

A Proposal for a Section of an LDS Church History Textbook for High School Students Containing the History of the Church from 1898 to 1951

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1966 A Proposal for a Section of an LDS Church History Textbook for High School Students Containing the History of the Church from 1898 to 1951 Arthur R. Bassett Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bassett, Arthur R., "A Proposal for a Section of an LDS Church History Textbook for High School Students Containing the History of the Church from 1898 to 1951" (1966). Theses and Dissertations. 4509. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4509 This Selected Project is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A PROPOSAL FOR A SECTION OF AN L.D. S. CHURCH HISTORY TEXTBOOK FOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS CONTAINING THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH FROM 1898 TO 1951 A Field Project Presented To The Department of Graduate Studies in Religious Instruction Brigham Young University Provo, Utah In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Religious Education by Arthur R. Bassett August 1966 PREFACE This field project had its beginning in an assignment given to the author in 1964. During the spring of that year he was commissioned by the seminary department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints1 to formulate a lesson plan for use in teaching a seminary course of study entitled "Church History and Doctrine." As will be shown later, the need for textual material dealing with the history of Mormonism2 from 1877 to the present arose during the writing of that lesson outline. -

A Revelation That Has Blessed the Whole World, P. 12 Noble Fatherhood: a Glimpse of the Divine, P

THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JUNE 2018 A Revelation That Has Blessed the Whole World, p. 12 Noble Fatherhood: A Glimpse of the Divine, p. 22 Selfless Service to the Suffering, p. 26 “I Have Got the Plates,” Joseph Cried, p. 32 “NOBLE FATHERHOOD GIVES US A GLIMPSE OF THE DIVINE ATTRIBUTES OF OUR FATHER IN HEAVEN.” PRESIDENT JAMES E. FAUST From “A Righteous Father’s Influence,” page 22. Liahona, June 2018 FEATURE ARTICLES 22 A Righteous Father’s Influence By Megan Warren The father figures in my life taught me about the importance of righ- teous fatherhood. 26 Bearing One Another’s Burdens By Elder Jeffrey R. Holland By showing Christlike empathy to all of God’s children, we can par- ticipate in the work of the Master. 32 Saints: The Story of the COMMEMORATING THE 1978 REVELATION Church—Chapter 4: Be Watchful After years of waiting, Joseph Smith 12 Extending the Blessings of 16 Revelation for Our Time finally receives the plates—with the the Priesthood Four Apostles recall how they admonition to be watchful. How the 1978 revelation regard- felt on June 1, 1978, when the ing the priesthood has blessed revelation on the priesthood was individuals, families, and the received. DEPARTMENTS Church. 18 Blessed in Every Way 4 Portraits of Faith: Delva Netane Possible By Elder Edward Dube 6 Ministering Principles: Five As a full-time missionary, I Things Good Listeners Do first heard about the priesthood 10 Serving in the Church: Where restriction for blacks. We Were Needed The Priesthood Held in High By Wilfried and Laura Eyi 20 Esteem 40 Latter-day Saint Voices By Charlotte Acquah I was baptized just three months 80 Until We Meet Again: Our after the first missionaries Sabbath Sanctuary arrived in Ghana. -

Religion As a Role: Decoding Performances of Mormonism in the Contemporary United States

RELIGION AS A ROLE: DECODING PERFORMANCES OF MORMONISM IN THE CONTEMPORARY UNITED STATES Lauren Zawistowski McCool A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Dr. Jonathan Chambers Dr. Lesa Lockford © 2012 Lauren Zawistowski McCool All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Although Mormons have been featured as characters in American media since the nineteenth century, the study of the performance of the Mormon religion has received limited attention. As Mormonism (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) continues to appear as an ever-growing topic of interest in American media, there is a gap in discourse that addresses the implications of performances of Mormon beliefs and lifestyles as performed by both members of the Church and non-believers. In this thesis, I closely examine HBO’s Big Love television series, the LDS Church’s “I Am a Mormon” media campaign, Mormon “Mommy Blogs” and the personal performance of Mormons in everyday life. By analyzing these performances through the lenses of Stuart Hall’s theories of encoding/decoding, Benedict Anderson’s writings on imagined communities, and H. L. Goodall’s methodology for the new ethnography the aim of this thesis is to fill in some small way this discursive and scholarly gap. The analysis of performances of the Mormon belief system through these lenses provides an insight into how the media teaches and shapes its audience’s ideologies through performance. iv For Caity and Emily.