Louisiana's Constitution of 1845 and the Clash of the Common Law And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water

Florida State University Law Review Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 1 Fall 1975 The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water Glenn J. MacGrady Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Glenn J. MacGrady, The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water, 3 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 511 (1975) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol3/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 3 FALL 1975 NUMBER 4 THE NAVIGABILITY CONCEPT IN THE CIVIL AND COMMON LAW: HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT, CURRENT IMPORTANCE, AND SOME DOCTRINES THAT DON'T HOLD WATER GLENN J. MACGRADY TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ---------------------------- . ...... ..... ......... 513 II. ROMAN LAW AND THE CIVIL LAW . ........... 515 A. Pre-Roman Legal Conceptions 515 B. Roman Law . .... .. ... 517 1. Rivers ------------------- 519 a. "Public" v. "Private" Rivers --- 519 b. Ownership of a River and Its Submerged Bed..--- 522 c. N avigable R ivers ..........................................- 528 2. Ownership of the Foreshore 530 C. Civil Law Countries: Spain and France--------- ------------- 534 1. Spanish Law----------- 536 2. French Law ----------------------------------------------------------------542 III. ENGLISH COMMON LAw ANTECEDENTS OF AMERICAN DOCTRINE -- --------------- 545 A. -

The Influence of Technological and Scientific Innovation on Personal Insurance

THE INFLUENCE OF TECHNOLOGICAL AND SCIENTIFIC INNOVATION ON PERSONAL INSURANCE Speakers: Dr. Eduardo Mangialardi Dr. Norberto Jorge Pantanali Dr. Enrique José Quintana I – GENERAL INTRODUCTION It is a great honour for the Argentine Association of Insurance Law, to have been entrusted by the Presidency Council of the International Association of Insurance Law (AIDA, for its Spanish acronym) the responsibility to prepare the questionnaire sent to all the National Sections and the elaboration and account of the general report referred to the subject “The Influence of Technological and Scientific Innovation on Personal Insurance”, in this XII World Conference of Insurance Law.- We think that the history and experience of the qualified jurists of the Argentine Section that preceded us had a great influence on the choice of our country as seat for such great academic event and to confer on us the distinction of this presentation. We cannot help remembering here and now that Drs. Juan Carlos Félix Morandi and Eduardo Steinfeld attended the First World Conference of Insurance Law held in Rome from April 4 to 7, 1962. We cannot help remembering that two former Presidents of our Association had the privilege of being the speakers of the general reports at the World Conferences of Insurance Law. Dr. Isaac Halperin developed the subject “The Insurance and the Acts of Violence Against the Community Affecting People or Assets” in the IV World Conference held in Laussane, Switzerland in April 1974, and Dr. Juan Carlos Félix Morandi, who at the VII World Conference held in Budapest, Hungary in May 1986, dealt with “Aggravation and Other Risk Modifications”. -

Spine for Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law

Spine for Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law Top to Bottom Vol. 32 Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law 2015 THE STEPHAN KUTTNER INSTITUTE OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW MÜNCHEN 2015 BULLETIN OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW NEW SERIES VOLUME 32 AN ANNUAL REVIEW PUBLISHED BY THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS FOR THE STEPHAN KUTTNER INSTITUTE OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW BULLETIN OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW THE STEPHAN KUTTNER INSTITUTE OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW MÜNCHEN 2015 BULLETIN OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW NEW SERIES VOLUME 32 AN ANNUAL REVIEW PUBLISHED BY THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS FOR THE STEPHAN KUTTNER INSTITUTE OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW Published annually at the Stephan Kuttner Institute of Medieval Canon Law Editorial correspondence should be addressed to: STEPHAN-KUTTNER INSTITUTE OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW Professor-Huber-Platz 2 D-80539 München PETER LANDAU, Editor Universität München [email protected] or KENNETH PENNINGTON, Editor The School of Canon Law The Catholic University of America Washington, D.C. 20064 [email protected] Advisory Board PÉTER CARDINAL ERDP PETER LINEHAN Archbishop of Esztergom St. John’s College Budapest Cambridge University JOSÉ MIGUEL VIÉJO-XIMÉNEZ ORAZIO CONDORELLI Universidad de Las Palmas de Università degli Studi Gran Canaria Catania FRANCK ROUMY KNUT WOLFGANG NÖRR Université Panthéon-Assas Universität Tübingen Paris II Inquiries concerning subscriptions or notifications of change of address should be sent to the Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law Subscriptions, PO Box 19966, Baltimore, MD 21211-0966. Notifications can also be sent by email to [email protected] Telephone (410) 516-6987 or 1-800-548-1784 or fax 410-516-3866. -

Browsing Through Bias: the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies

Browsing through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies Sara A. Howard and Steven A. Knowlton Abstract The knowledge organization system prepared by the Library of Con- gress (LC) and widely used in academic libraries has some disadvan- tages for researchers in the fields of African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. The interdisciplinary nature of those fields means that browsing in stacks or shelflists organized by LC Classification requires looking in numerous locations. As well, persistent bias in the language used for subject headings, as well as the hierarchy of clas- sification for books in these fields, continues to “other” the peoples and topics that populate these titles. This paper offers tools to help researchers have a holistic view of applicable titles across library shelves and hopes to become part of a larger conversation regarding social responsibility and diversity in the library community.1 Introduction The neat division of knowledge into tidy silos of scholarly disciplines, each with its own section of a knowledge organization system (KOS), has long characterized the efforts of libraries to arrange their collections of books. The KOS most commonly used in American academic libraries is the Li- brary of Congress Classification (LCC). LCC, developed between 1899 and 1903 by James C. M. Hanson and Charles Martel, is based on the work of Charles Ammi Cutter. Cutter devised his “Expansive Classification” to em- body the universe of human knowledge within twenty-seven classes, while Hanson and Martel eventually settled on twenty (Chan 1999, 6–12). Those classes tend to mirror the names of academic departments then prevail- ing in colleges and universities (e.g., Philosophy, History, Medicine, and Agriculture). -

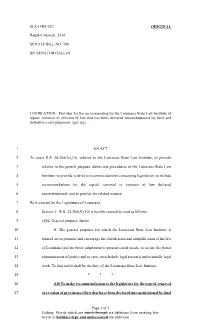

C:\TEMP\Copy of SB180 Original (Rev 0).Wpd

SLS 14RS-257 ORIGINAL Regular Session, 2014 SENATE BILL NO. 180 BY SENATOR GALLOT LEGISLATION. Provides for the recommending by the Louisiana State Law Institute of repeal, removal or revision of law that has been declared unconstitutional by final and definitive court judgment. (gov sig) 1 AN ACT 2 To enact R.S. 24:204(A)(10), relative to the Louisiana State Law Institute; to provide 3 relative to the general purpose, duties and procedures of the Louisiana State Law 4 Institute; to provide relative to recommendations concerning legislation; to include 5 recommendations for the repeal, removal or revision of law declared 6 unconstitutional; and to provide for related matters. 7 Be it enacted by the Legislature of Louisiana: 8 Section 1. R.S. 24:204(A)(10) is hereby enacted to read as follows: 9 §204. General purpose; duties 10 A. The general purposes for which the Louisiana State Law Institute is 11 formed are to promote and encourage the clarification and simplification of the law 12 of Louisiana and its better adaptation to present social needs; to secure the better 13 administration of justice and to carry on scholarly legal research and scientific legal 14 work. To that end it shall be the duty of the Louisiana State Law Institute: 15 * * * 16 (10) To make recommendations to the legislature for the repeal, removal 17 or revision of provisions of law that have been declared unconstitutional by final Page 1 of 3 Coding: Words which are struck through are deletions from existing law; words in boldface type and underscored are additions. -

Recent Cases

Missouri Law Review Volume 37 Issue 4 Fall 1972 Article 8 Fall 1972 Recent Cases Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Recent Cases, 37 MO. L. REV. (1972) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol37/iss4/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Recent Cases Recent Cases CIVIL RIGHTS-TITLE VII OF CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964- DISMISSAL FROM EMPLOYMENT OF MINORITY-GROUP EMPLOYEE FOR EXCESSIVE WAGE GARNISHMENT Johnson v. Pike Corp. of America' Defendant corporation employed plaintiff, a black man, as a ware- houseman. Several times during his employment, plaintiff's wages were garnished to satisfy judgments. Defendant had a company rule stating, "Conduct your personal finances in such a way that garnishments will not be made on your wages," 2 and a policy of discharging employees whose wages were garnished in contravention of this rule. Pursuant to that policy, defendant dismissed plaintiff for violating the company rule. Plaintiff filed an action alleging that the practice causing his dismissal constituted discrimination against him because of race and, hence, violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Section 703 of Title VII provides: a. It shall be unlawful employment practice for an employer- 1. -

FALL 2009 Vented the Idea of Democracy

TULANEUNIVERSITYLAWSCHOOL TULANE VOL. 27–NO. 2 LAWYER F A L L 2 0 0 9 TAKING THE LAW THISISSUE IN THEI RHANDS ALETTERFROMINTERIM DEANSTEPHENGRIFFIN TULANELAWSTUDENTS I CLASSICALATHENIAN ANCESTRYOFAMERICAN ACTINTHEPUBLICINTEREST FREEDOMOFSPEECH I HONORROLLOFDONORS STEPHENGRIFFIN INTERIMDEAN LAURENVERGONA EDITORANDEXECUTIVEASSISTANTTOTHEINTERIMDEAN ELLENJ.BRIERRE DIRECTOROFALUMNIAFFAIRS TA NA C O M A N ARTDIRECTIONANDDESIGN SHARONFREEMAN DESIGNANDPRODUCTION CONTRIBUTORS LINDSAY ELLIS KATHRYN HOBGOOD NICKMARINELLO M A RY M O U TO N TULANELAWSCHOOLHONORROLLOFDONORS N E W WAV E S TA F F Donor lists originate from the Tulane University Office of Development. HOLMESRACKLEFF Lists are cataloged in compliance with the Tulane University Style Guide, using a standard format which reflects name preferences defined in the RYA N R I V E T university-wide donor database, unless a particular donation requires FRANSIMON specific donors’ preferences. TULANEDEVELOPMENT TULANE LAW CLINIC CONTRIBUTORS LIZBETHTURNER NICOLEDEPIETRO BRADVOGEL MICHAELHARRINGTON KEITHWERHAN ANDREWROMERO TULANELAWYER is published by the PHOTOGRAPHY Tulane Law School and is sent to the school’s JIM BLANCHARD, illustration, pages 3, 49, 63; CLAUDIA L. BULLARD, page alumni, faculty, staff and friends. 39; PAULA BURCH-CELENTANO/Tulane University Publications, inside cover, pages 2, 8, 12, 32, 48, 50, 53, 62; FEDERAL LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CENTER COMMITTEE, page 42; GLOBAL ENERGY GROUP LTD., page 10; JACKSON HILL, Tulane University is an Affirmative Action/Equal pages 24–25; BÍCH LIÊN, page 40 bottom;THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR Employment Opportunity institution. RESEARCH ON WOMEN, page 38; TRACIEMORRISSCHAEFER/Tulane University Publications, pages 44–45, 57; ANDREWSEIDEL, page 11; SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LTD., page 40 top; TULANE PUBLIC RELATIONS, page 47, outer back cover;EUGENIAUHL, pages 1, 26–28, 31, 33;TOM VARISCO, page 51; LAUREN VERGONA, pages 6, 7, 45–46; WALEWSKA M. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1823, TO MARCH 3, 1825 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1823, to May 27, 1824 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1824, to March 3, 1825 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 2 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 3 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland; JOHN O. DUNN, 4 of District of Columbia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN BIRCH, of Maryland ALABAMA GEORGIA Waller Taylor, Vincennes SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William R. King, Cahaba John Elliott, Sunbury Jonathan Jennings, Charlestown William Kelly, Huntsville Nicholas Ware, 8 Richmond John Test, Brookville REPRESENTATIVES Thomas W. Cobb, 9 Greensboro William Prince, 14 Princeton John McKee, Tuscaloosa REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Gabriel Moore, Huntsville Jacob Call, 15 Princeton George W. Owen, Claiborne Joel Abbot, Washington George Cary, Appling CONNECTICUT Thomas W. Cobb, 10 Greensboro KENTUCKY 11 SENATORS Richard H. Wilde, Augusta SENATORS James Lanman, Norwich Alfred Cuthbert, Eatonton Elijah Boardman, 5 Litchfield John Forsyth, Augusta Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Henry W. Edwards, 6 New Haven Edward F. Tattnall, Savannah Isham Talbot, Frankfort REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Wiley Thompson, Elberton REPRESENTATIVES Noyes Barber, Groton Samuel A. Foote, Cheshire ILLINOIS Richard A. Buckner, Greensburg Ansel Sterling, Sharon SENATORS Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Stoddard, Woodstock Jesse B. Thomas, Edwardsville Robert P. Henry, Hopkinsville Gideon Tomlinson, Fairfield Ninian Edwards, 12 Edwardsville Francis Johnson, Bowling Green Lemuel Whitman, Farmington John McLean, 13 Shawneetown John T. -

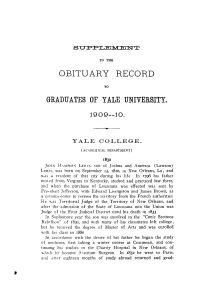

Obituary Record

S U TO THE OBITUARY RECORD TO GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVEESITY. 1909—10. YALE COLLEGE. (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1832 JOHN H \MPDFN LEWIS, son of Joshua and America (Lawson) Lewis, was born on September 14, 1810, m New Orleans, La, and was a resident of that city during his life In 1796 his father moved from Virginia to Kentucky, studied and practiced law there, and when the purchase of Louisiana was effected was sent by President Jefferson, with Edward Livingston and James Brown, as a commisMoner to receive the territory from the French authorities He was Territorial Judge of the Territory of New Orleans, and after the admission of the State of Louisiana into the Union was Judge of the First Judicial District until his death in 1833 In Sophomore year the son was involved in the "Conic Sections Rebellion" of 1830, and with many of his classmates left college, but he received the degree of Master of Arts and was enrolled with his class in 1880 In accordance with the desire of his father he began the study of medicine, first taking a winter course at Cincinnati, and con- tinuing his studies in the Charity Hospital in New Orleans, of which he became Assistant Surgeon In 1832 he went to Pans, and after eighteen months of study abroad returned and grad- YALE COLLEGE 1339 uated in 1836 with the first class from the Louisiana Medical College After having charge of a private infirmary for a time he again went abroad for further study In order to obtain the nec- essary diploma in arts and sciences he first studied in the Sorbonne after which he entered -

18-5924 Respondent BOM.Wpd

No. 18-5924 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________________ EVANGELISTO RAMOS, Petitioner, v. LOUISIANA, Respondent. __________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Louisiana, Fourth Circuit __________________ BRIEF OF RESPONDENT __________________ JEFF LANDRY LEON A. CANNIZZARO. JR. Attorney General District Attorney, ELIZABETH B. MURRILL Parish of Orleans Solicitor General Donna Andrieu Counsel of Record Chief of Appeals MICHELLE GHETTI 619 S. White Street Deputy Solicitor General New Orleans, LA 70119 COLIN CLARK (504) 822-2414 Assistant Attorney General LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE WILLIAM S. CONSOVOY 1885 North Third Street JEFFREY M. HARRIS Baton Rouge, LA 70804 Consovoy McCarthy PLLC (225) 326-6766 1600 Wilson Blvd., Suite 700 [email protected] Arlington, VA 22209 Counsel for Respondent August 16, 2019 Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether this Court should overrule Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972), and hold that the Sixth Amendment, as incorporated through the Fourteenth Amendment, guarantees State criminal defendants the right to a unanimous jury verdict. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED.................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................... iv STATEMENT............................... 1 A.Factual Background..................1 B.Procedural History...................2 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................. 4 ARGUMENT.............................. 11 I. THE SIXTH AMENDMENT’S JURY TRIAL CLAUSE DOES NOT REQUIRE UNANIMITY .......... 11 A. A “Trial By Jury” Under the Sixth Amendment Does Not Require Every Feature of the Common Law Jury......11 B. A Unanimous Verdict Is Not an Indispensable Component of a “Trial By Jury.”............................ 20 1. There is inadequate historical support for unanimity being indispensable to a jury trial...................... -

Louisiana Property Law—The Civil Code, Cases and Commentary

Journal of Civil Law Studies Volume 8 Number 2 Article 9 12-31-2015 Louisiana Property Law—The Civil Code, Cases and Commentary Yaëll Emerich Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls Part of the Civil Law Commons Repository Citation Yaëll Emerich, Louisiana Property Law—The Civil Code, Cases and Commentary, 8 J. Civ. L. Stud. (2015) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls/vol8/iss2/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Law Studies by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS JOHN A. LOVETT, MARKUS G. PUDER & EVELYN L. WILSON, LOUISIANA PROPERTY LAW—THE CIVIL CODE, CASES AND COMMENTARY (Carolina Academic Press, Durham, North Carolina 2014) Reviewed by Yaëll Emerich* Although this interesting work, by John A. Lovett, Markus G. Puder and Evelyn L. Wilson, styles itself as “a casebook about Louisiana property law,”1 it nevertheless has some stimulating comparative insights. The book presents property scholarship from the United States and beyond, taking into account property texts from other civilian and mixed jurisdictions such as Québec, South Africa and Scotland. As underlined by the authors, Louisiana’s system of property law is a part of the civilian legal heritage inherited from the French and Spanish colonisation and codified in its Civil Code: “property law . is one of the principal areas . where Louisiana´s civilian legal heritage has been most carefully preserved and where important substantive differences between Louisiana civil law and the common law of its sister states still prevail.”2 While the casebook mainly scrutinizes Louisiana jurisprudence and its Civil Code in local doctrinal context, it also situates Louisiana property law against a broader historical, social and economic background. -

The French Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: a Requiem, 57 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 57 | Number 4 Summer 1997 The rF ench Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: A Requiem Roger K. Ward Repository Citation Roger K. Ward, The French Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: A Requiem, 57 La. L. Rev. (1997) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol57/iss4/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT The French Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: A Requiem* I. INTRODUCTION Anyone familiar with the celebrated works of the sixteenth century French satirist Frangois Rabelais is sure to remember the protagonist Pantagruel's encounter with the Limousin scholar outside the gates of Orldans.1 During his peregrinations, the errant Pantagruel happens upon the Limousin student who, in response to a simple inquiry, employs a gallicized form of Latin in order to show off how much he has learned at the university.? The melange of French and Latin is virtually incomprehensible to Pantagruel, prompting him to exclaim, "What the devil kind of language is this?"' 3 Determined to understand the student, Pantagruel launches into a series of straightforward and easily answerable questions. The Limousin scholar, however, responds to each question using the same unintelligi- ble, bastardized form of Latin." The pretentious use of pseudo-Latin in lieu of the French vernacular infuriates Pantagruel and causes him to physically assault the student.