Aublr 6N3 Text Low.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

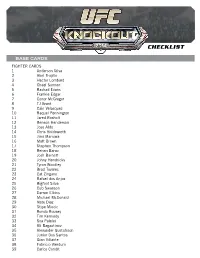

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

Introducing Participatory Geographic Information and Multimedia Systems in Two Indonesian Communities

Empowering Technologies? Introducing Participatory Geographic Information and Multimedia Systems in two Indonesian Communities by Jon Corbett B.A., University of Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1989 M.Sc., University of Oxford, 1995 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Geography We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Dr. C. P. Ki ervisor (Bèoartment Geography) Dr. P. Dearden, DepartWteij^l Member (^p artm en t of Geography) Dr. C. Wood,y^(IarttTientel Member (Department of Geography) ____________________ Dr. M I Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. T Examiner (Department of Geology and Geography, West Virginia University) © Jon Corbett, 2003 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. 11 Supervisor: Dr. C. P. Keller ABSTRACT Inclusion of local knowledge in decision-making is recognized as important for land-use planning. However, this is prevented by communication constraints. Increasingly local communities throughout the world are using community mapping and simple Geographic Information Technologies (GIT) to communicate information about traditional lands to decision makers. This corresponds to the trend, primarily in North America, for practitioners to apply Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technologies in public participation settings. Claims have been made that use of Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGIS) by disadvantaged groups can be empowering. However, others claim that PPGIS is disempowering due to the cost and complexity of the technologies, inaccessibility of data, restrictive representation of local geographic information, and the low level of community participation. -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos Vs

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos vs. Alvarez Live Main Card Highlights UFC 200 Fight Week Coverage on Fight Network Toronto – Fight Network, the world’s premier 24/7 multi- platform channel dedicated to complete coverage of combat sports, today announced extensive live coverage for UFC International Fight Week™ in Las Vegas, the biggest week in UFC history, highlighted by a live broadcast of the main card for UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ from the MGM Grand Garden Arena on Thursday, July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, plus the live prelims for THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE®: Team Joanna vs. Team Claudia on Friday, July 8 at 8 p.m. ET. Fight Network will air the live UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ main card across Canada on July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, preceded by a live Pre-Show at 9 p.m. ET. In the main event, dominant UFC lightweight champion Rafael dos Anjos (24-7) puts his championship on the line in a five- round barnburner against top contender Eddie Alvarez (27-4). In other featured bouts, Roy “Big Country” Nelson (22-12) throws down with Derrick “The Black Beast” Lewis (15-4, 1NC) in an explosive heavyweight collision, Alan Jouban (13-4) takes on undefeated Belal Muhammad (9-0) in a welterweight affair, plus “Irish” Joe Duffy (14-2) welcomes Canada’s Mitch “Danger Zone” Clarke (11-3) back to action in a lightweight matchup. Live fight week coverage begins on Wednesday, July 6 at 2 p.m. ET with a live presentation of the final UFC 200 pre-fight press conference, featuring UFC president Dana White and main card superstars Jon Jones, Daniel Cormier, Brock Lesnar, Mark Hunt, Miesha Tate, Amanda Nunes, Jose Aldo and Frankie Edgar. -

Are Ufc Fighters Employees Or Independent Contractors?

Conklin Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/27/20 8:42 PM TWO CLASSIFICATIONS ENTER, ONE CLASSIFICATION LEAVES: ARE UFC FIGHTERS EMPLOYEES OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS? MICHAEL CONKLIN* I. INTRODUCTION The fighters who compete in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“UFC”) are currently classified as independent contractors. However, this classification appears to contradict the level of control that the UFC exerts over its fighters. This independent contractor classification severely limits the fighters’ benefits, workplace protections, and ability to unionize. Furthermore, the friendship between UFC’s brash president Dana White and President Donald Trump—who is responsible for making appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”)—has added a new twist to this issue.1 An attorney representing a former UFC fighter claimed this friendship resulted in a biased NLRB determination in their case.2 This article provides a detailed examination of the relationship between the UFC and its fighters, the relevance of worker classifications, and the case law involving workers in related fields. Finally, it performs an analysis of the proper classification of UFC fighters using the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) Twenty-Factor Test. II. UFC BACKGROUND The UFC is the world’s leading mixed martial arts (“MMA”) promotion. MMA is a one-on-one combat sport that combines elements of different martial arts such as boxing, judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, and karate. UFC bouts always take place in the trademarked Octagon, which is an eight-sided cage.3 The first UFC event was held in 1993 and had limited rules and limited fighter protections as compared to the modern-day events.4 UFC 15 was promoted as “deadly” and an event “where anything can happen and probably will.”6 The brutality of the early UFC events led to Senator John * Powell Endowed Professor of Business Law, Angelo State University. -

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta Sportovních Studií

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra podpory zdraví Definice rizik a návrh jejich odstranění v silové přípravě zápasníků v ultimátních sportech Bakalářská práce Brno 2017 Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Ing. Iva Hrnčiříková, Ph.D. Vypracoval: Martin Šmíd SEBS Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci zpracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v seznamu literatury. V Brně dne 2. května 2017 --------------------------------------- Poděkování Rád bych poděkoval především vedoucímu mé bakalářské práce za udělené konzultace a rady při zpracování mé práce, trenérům a zápasníkům smíšených bojových umění za poskytnuté cenné rady a zkušenosti. Obsah 1. Smíšená bojová umění (MMA)....................................................................................... 9 1.1. Charakteristika smíšených bojových umění (MMA)............................................... 9 1.2. Historie smíšených bojových umění (MMA) .......................................................... 9 1.3. Světové Organizace smíšených bojových umění (MMA) ..................................... 11 1.3.1. Ultimate Fight Championship (UFC) ............................................................. 11 1.3.4. Rizin Fighting Federation (RIZIN FF) ........................................................... 11 1.3.5. M1-Global ...................................................................................................... 11 1.4. České Organizace smíšených bojových umění (MMA) ........................................ 12 1.4.1. Gladiator Championship -

Any Spares? I'll Buy Or Sell: an Ethnographic Study of Black Market Ticket Sales

Any spares? I’ll buy or sell: An ethnographic study of black market ticket sales ALESSANDRO MORETTI A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2017 DECLARATION “I certify that the work contained in this thesis, or any part of it, has not been accepted in substance for any previous degree awarded to me, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise identified by references and that the contents are not the outcome of any form of research misconduct.” Signed: Date: Alessandro Moretti 31.03.2017 ___________________________ _______________________ Alessandro Moretti Darrick Jolliffe 31.03.2017 ___________________________ _______________________ Professor Darrick Jolliffe ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my family, and in particular my mother Giuliana, who has been immeasurably supportive, patient, and strong in all these years. Thank you to my friends, at home and abroad, who have always believed in me. I am grateful for the valuable inputs of my supervisor, Professor Darrick Jolliffe, and his ability to keep me motivated. One research participant deserves a special mention: thank you to “The Chameleon”, who is now a friend more than he is a tout. Finally, a special thank you to Lorna, without whom I would never have completed this work. iii ABSTRACT This thesis contributes to the limited knowledge on ticket touting and ticket touts. -

Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want to Share: an Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports

Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 5 8-1-2018 Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports Daniel L. Maschi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel L. Maschi, Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports, 25 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 409 (2018). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol25/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\25-2\VLS206.txt unknown Seq: 1 26-JUN-18 12:26 Maschi: Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitr MILLION DOLLAR BABIES DO NOT WANT TO SHARE: AN ANALYSIS OF ANTITRUST ISSUES SURROUNDING BOXING AND MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND WAYS TO IMPROVE COMBAT SPORTS I. INTRODUCTION Coined by some as the “biggest fight in combat sports history” and “the money fight,” on August 26, 2017, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) mixed martial arts (MMA) superstar, Conor McGregor, crossed over to boxing to take on the biggest -

Estta929927 10/22/2018 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA929927 Filing date: 10/22/2018 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91244214 Party Plaintiff Zuffa, LLC Correspondence M. Feder, J. Krieger, R. Kouchoukos Address Dickinson Wright PLLC 8363 West Sunset Road, Ste. 200 Las Vegas, NV 89113 UNITED STATES [email protected] 7025504400 Submission Other Motions/Papers Filer's Name Robert B. Kouchoukos Filer's email [email protected] Signature /Robert B. Kouchoukos/ Date 10/22/2018 Attachments Errata to notice of opposition to submit exhibits.pdf(4071891 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Zuffa, LLC, a Nevada limited liability company, Mark: Opposer, v. Patrick A. Whitney, an individual domiciled in Maryland. Applicant. Opposition No.: 91244214 Ser. No.: 87197128 Published: June 26, 2018 Class: 41 ERRATA TO NOTICE OF OPPOSITION Opposer by and through their attorneys hereby amend its Notice of Opposition timely filed on October 18, 2018, to submit referenced Exhibit 1, which was inadvertently omitted from the electronic filing. Dated: October 22, 2018. Respectfully submitted, DICKINSON WRIGHT PLLC /Robert B. Kouchoukos/ Michael N. Feder, Esq. [email protected] John L. Krieger, Esq. [email protected] Robert B. Kouchoukos, Esq. [email protected] 8363 West Sunset Road, Suite 200 Las Vegas, Nevada 89113 (702) 550-4400 (phone) (844) 670-6009 (fax) ERRATA TO NOTICE OF OPPOSITION I hereby certify that, on October 22, 2018, a true and complete copy of the foregoing ERRATA TO NOTICE OF OPPOSITION has been served by electronic mail on the Applicant to: Patrick A. -

Woodstock, CT 06281 (860) 928-1818 Ext

Vol. X, No. 7 Complimentary Friday, November 14, 2014 (860) 928-1818/e-mail: [email protected] THIS WEEK’S QUOTE Boy Scouts collect food “The truth is the kindest thing we can give folks in for Daily Bread the end.” MORE THAN Harriet Beecher Stowe 1,000 POUNDS DONATED TO LOCAL INSIDE FOOD BANK A8 — OPINION BY JASON BLEAU NEWS STAFF WRITER B1-4 — SPORTS PUTNAM — The hol- B6 — LEGALS idays are upon us, and B7 — REAL ESTATE while many may be com- fortable with their situ- B5-6— OBITS ation in life, others are B9-11 — CLASSIFIEDS barely getting by and may find it hard to provide a fitting meal this holiday Jason Bleau photos season. Boy Scouts from Troop 21 in Putnam display some of the food It’s this fact that helps LOCAL collected during their Nov. 8 food drive to benefit Daily Bread. inspire during the sea- son of giving and in At right: Northeastern Connecticut Chris Dundon, Junior Assistant Charlie Lentz photo things got off to a quick Scout Master of Troop 21, start with the Boy Scout and Carlo Lombardo, Assistant Troop 21 and Cargill Scout Master of Troop 21 TURKEY TROT Council 64 Food Drive on and Recorder for Knights of Nov. 8. Columbus Council 64, show THOMPSON — John Minervino and his For the bulk of the morn- some of the donations collected daughter, Brianna, from Haddam were two of ing, scouts from Troop 21 outside of Putnam Supermarket the more than 300 runners and walkers that stationed themselves at during the food drive on Nov. -

Impoliteness Strategies in Ufc Press Conference

IMPOLITENESS STRATEGIES IN UFC PRESS CONFERENCE THESIS BY: SOFIYAN HADI REG. NUMBER: A73216132 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES UIN SUNAN AMPEL SURABAYA 2020 ABSTRACT Hadi, Sofiyan. (2020). Impoliteness Strategies in UFC Press Conference. English Department, Faculty of Arts and Humanities. UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya. Advisor: Dr. A. Dzo'ul Milal, M.Pd. Keywords; Impoliteness, Politeness, Press Conference, Entertainment. __________________________________________________________________ This thesis aimed at examining the use of impoliteness in the UFC Press Conference. The phenomena of impoliteness can be found in any human interaction. It also can be found in any situation. One of them is entertainment. One of the entertainments show is UFC. This thesis examines the impoliteness strategies in UFC Press Conference. This study aims to analyze the use of impoliteness done by Conor McGregor and its responses done by Khabib Nurmagomedov. Furthermore, this thesis also analyzes entertainment factors that trigger the use of impoliteness done by McGregor. The press conference of UFC 229 between Conor McGregor and Khabib Nurmagomedov is selected as the data of this study. In this research, the researcher applies Culpeper's (2005) framework about impoliteness and its responses. Moreover, Culpeper’s theory about generic factors is applied. The researcher in this study applies a qualitative approach. In order to collect the data, the researcher transcribes press conference video into transcription text. The researcher underlines and gives codes to all sentences, words, and phrases that contain impoliteness and their responses. Since this study is in the entertainment area, the researcher interprets the data in order to examine the entertainment factors that trigger the use of McGregor's impoliteness.