Myanmar's 2020 Elections and Conflict Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

Hakha Chin Land and Resource Tenure Resource and Land Chin Hakha in Change and Persistence

PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCETENURE PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of and Lives Land series Myanmar research Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series DISCLAIMER Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land This document is supported with financial assistance from Australia, Denmark, dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. the European Union, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Published by GRET, 2018 the Mitsubishi Corporation. The views expressed herein are not to be taken to reflect the official opinion of any of the LIFT donors. Suggestion for citation: Boutry, M., Allaverdian, C. Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone. (2018). Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. Of lives of land Myanmar research series. GRET: Yangon. Written by: Maxime Boutry and Celine Allaverdian With the contributions of: Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone and Sung Chin Par Reviewed by: Paul Dewit, Olivier Evrard, Philip Hirsch and Mark Vicol Layout by: studio Turenne Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series The Of Lives and Land series emanates from in-depth socio-anthropological research on land and livelihood dynamics. -

New Government's Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar

CHAPTER 2 New Government’s Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar Aung Min and Toshihiro KUDO This chapter should be cited as: Aung Min and Kudo, K., 2012. “New Government’s Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar.” In Economic Reforms in Myanmar: Pathways and Prospects, edited by Hank Lim and Yasuhiro Yamada, BRC Research Report No.10, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. Chapter 2 New Government’s Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar Aung Min and Toshihiro KUDO Abstract Since 1988, when the State Law and Order Restoration Council (military government) assumed state responsibility, the market has been partially opened to the outside world. Myanmar's industrialization has shown little progress as the previous government’s1 policies and poor international relations hampered FDI inflows. As the new “elected” government took office in 2011, significant changes in policies have taken place and this paper intends to highlight the efforts of the new government in its attempt to enhance industrial development. The paper assesses the performance of related union-level ministries and regional governments towards industrial development through establishing industrial zones in all states and regions, except the Chin and Kayah states. The establishment of seven new industrial zones and extension of 18 existing industrial zones is seen to have a positive effect on industrial development, although improvements in infrastructural facilities need to be realized. Introducing the SME Service Centre in Yangon and SME financing schemes enables the firms to obtain loans from the newly named Small and Medium Industrial Development Bank (SMIDB)2, thus contributing to SME development to some extent. -

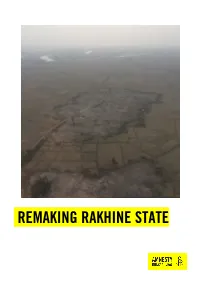

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

Burma - Conduct of Elections and the Release of Opposition Leader Aung San Suu Kyi

C 99 E/120 EN Official Journal of the European Union 3.4.2012 Thursday 25 November 2010 Burma - conduct of elections and the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi P7_TA(2010)0450 European Parliament resolution of 25 November 2010 on Burma – conduct of elections and the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi (2012/C 99 E/23) The European Parliament, — having regard to its previous resolutions on Burma, the most recent adopted on 20 May 2010 ( 1 ), — having regard to Articles 18- 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948, — having regard to Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966, — having regard to the EU Presidency Statement of 23 February 2010 calling for all-inclusive dialogue between the authorities and the democratic forces in Burma, — having regard to the statement of the President of the European Parliament Jerzy Buzek of 11 March 2010 on Burma’s new election laws, — having regard to the Chairman’s Statement at the 16th ASEAN Summit held in Hanoi on 9 April 2010, — having regard to the Council Conclusions on Burma adopted at the 3009th Foreign Affairs Council meeting in Luxembourg on 26 April 2010, — having regard to the European Council Conclusions, Declaration on Burma, of 19 June 2010, — having regard to the UN Secretary-General’s report on the situation of human rights in Burma of 28 August 2009, — having regard to the statement made by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in Bangkok on 26 October 2010, — having regard to the Chair’s statement at the -

Law Relating Amyotha Hluttaw

The Union of Myanmar Chapter I The State Peace and Development Council Title, Enforcement and Definition The Law Relating to the Amyotha Hluttaw 1. (a) This Law shall be called the Law relating to the Amyotha ( The State Peace and Development Council Law No. 13 /2010 ) Hluttaw, The 13th Waxing Day of Thadinkyut , 1372 M.E. (b) This Law shall come into force throughout the country ( 21st October, 2010 ) commencing from the day of its promulgation. Preamble 2. The following expressions contained in this Law shall have the meanings Since it is provided in Section 443 of the Constitution of the Republic given hereunder: of the Union of Myanmar that the State Peace and Development Council shall (a) Constitution means the Constitution of the Republic of the carry out the necessary preparatory works to implement the Constitution, it has Union of Myanmar; become necessary to enact the relevant laws to enable performance of the legislative, administrative and judicial functions of the Union smoothly, to enable (b) Hluttaw means the Amyotha Hluttaw formed under the performance of works that are to be carried out when the various Hluttaws come Constitution for the purpose of this Law; into existence and to enable performance of the preparatory works in accord (c) Chairperson means the Hluttaw representative elected to with law. supervise the Hluttaw session until the Hluttaw Speaker and As such, the State Peace and Development Council hereby enacts this the Deputy Speaker are elected when the first session of a Law in accord with section 443 of the Constitution of the Republic of the Union term of Hluttaw commences; of Myanmar, in order to implement the works relating to Hluttaw smoothly in (d) Speaker means the Hluttaw representative elected as the convening the sessions of the Amyotha Hluttaw in accord with the Constitution Speaker of the Hluttaw for a term of the Hluttaw; of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. -

Political Monitor No.31

Euro-Burma Office 14 – 20 September 2013 Political Monitor 2013 POLITICAL MONITOR NO.31 OFFICIAL MEDIA PRESIDENT THEIN SEIN MEETS 88 GENERATION PEACE AND OPEN SOCIETY GROUP President Thein Sein held talks with the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society Group led by Min Ko Naing on 14 September. They held cordial discussions covered a wide range of issues including reconciliation, mapping of a new form of political culture, flourishing of democratic practices and promoting socio-economic status of the people and to work together in dealing with transitional challenges. Others issues included resolving land disputes, political prisoners and all inclusiveness of national races groups, political parties and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in the on-going peace process.1 CSOs, MEDIA PLAY CRUCIAL ROLE FOR FREE, FAIR ELECTIONS A media conference (2013) between the Union Election Commission and political parties, jointly organized by Myanmar Multiparty Democracy Programme and International Media Support (IMS), was held in Yangon on 14 September. In his speech, the Union Election Commission (UEC) Chairman Tin Aye said that a strategic plan is being drawn in cooperation to the holding of free and fair elections in 2015. Laws and bylaws which are being drafted and cooperation of all political parties is of prime importance for successful holding the elections. Tin Aye highlighted the crucial role of CSOs and media in ensuring a free and fair election and also called for the collaboration of all political parties, CSOs and media in the holding of elections.2 LAWMAKERS MEET TO PROTECT RIGHTS OF ETHNIC NATIONALITIES Hluttaw Speakers and officials met with Myanmar Parliamentarian Committee and Union Attorney- General and region/state advocates-general on 13 September to discuss the bill on protection of the rights of ethnic nationalities to cooperate in equalizing the different laws of Regions and States in legislative matters of the Union. -

Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer

www.ssoar.info Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. https:// doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: The Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Rainer Einzenberger ► Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier capitalism and politics of dispossession in Myanmar: The case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) nickel mine in Chin State. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. Since 2010, Myanmar has experienced unprecedented political and economic changes described in the literature as democratic transition or metamorphosis. The aim of this paper is to analyze the strategy of accumulation by dispossession in the frontier areas as a precondition and persistent element of Myanmar’s transition. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

FIGHTING VOTER SUPPRESSION PRESENTED by ELLEN PRICE -MALOY APRIL 26, 2021 VIDEOS to WATCH Stacey Abrams on 3 Ways Votes Are Suppressed – Youtube

FIGHTING VOTER SUPPRESSION PRESENTED BY ELLEN PRICE -MALOY APRIL 26, 2021 VIDEOS TO WATCH Stacey Abrams on 3 ways votes are suppressed – YouTube Stacey Abrams discussed with Jelani Cobb the three ways that voter suppression occurs in America: registration access restrictions, ballot access restriction... The History of U.S. Voting Rights | Things Explained Who can vote today looked a lot different from those who could vote when the United States was first founded. This video covers the history of voting rights, including women's suffrage, Black disenfranchisement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the various methods American voters can cast their ballots today. For more episodes, specials, and ... 2020 election: What is voter suppression? Tactics used against communities of color throughout history, in Trump-Biden race - ABC7 San Francisco NEW YORK -- As Election Day draws close, some American citizens have experienced barriers to voting, particularly in communities of color. While stories about voter suppression across the nation ... SUPPORT DEMOCRACY H.R.1/S.1 The legislation contains several provisions to fight voter suppression, including national automatic voter registration, prohibitions on voter roll purging and federal partisan gerrymandering, and improved election security measures. It also strengthens ethics providing a strong enforcement of Congress’ Ethics Code – leading to prosecution of those who break the Ethics code and standards and for all three branches of government, e.g. by requiring presidential candidates to disclose 10 years of tax returns and prohibiting members of Congress from using taxpayer dollars to settle sexual harassment cases. The bill aims to curb corporate influence in politics by forcing Super PACs to disclose their donors, requiring government contractors to disclose political spending, and prohibiting coordination between candidates and Super PACs, among other reforms. -

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar October 2020 About Us This report was written based on the information and data collection, monitoring, analytical insights and experiences with hate speech by civil society organizations working to reduce and/or directly af- fected by hate speech. The research for the report was coordinated by Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) and Progressive Voice and written with the assistance of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School while it is co-authored by a total 19 organizations. Jointly published by: 1. Action Committee for Democracy Development 2. Athan (Freedom of Expression Activist Organization) 3. Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) 4. Generation Wave 5. International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School 6. Kachin Women’s Association Thailand 7. Karen Human Rights Group 8. Mandalay Community Center 9. Myanmar Cultural Research Society 10. Myanmar People Alliance (Shan State) 11. Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica 12. Olive Organization 13. Pace on Peaceful Pluralism 14. Pon Yate 15. Progressive Voice 16. Reliable Organization 17. Synergy - Social Harmony Organization 18. Ta’ang Women’s Organization 19. Thint Myat Lo Thu Myar (Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement) Contact Information Progressive Voice [email protected] www.progressivevoicemyanmar.org Burma Monitor [email protected] International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School [email protected] https://hrp.law.harvard.edu Acknowledgments Firstly and most importantly, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to the activists, human rights defenders, civil society organizations, and commu- nity-based organizations that provided their valuable time, information, data, in- sights, and analysis for this report.