Cougar’ Stereotype

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skunk Ape: Stories and Poems

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 Skunk Ape: Stories and Poems Aaron Fallon College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Fallon, Aaron, "Skunk Ape: Stories and Poems" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 745. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/745 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Skunk Ape: Stories and Poems A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English from The College of William and Mary by Aaron Fallon Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Emily Pease, Director ________________________________________ Nancy Schoenberger ________________________________________ Henry Hart ________________________________________ Arthur Knight Williamsburg, VA April 16, 2010 1 Skunk Ape Aaron Fallon 2 For all she’s given me in support of this project I am deeply grateful to Emily Pease— her patience is truly boundless. 3 Mythologies…are great poems, and, when recognized as such, point infallibly through things and events to the ubiquity of a “presence” or “eternity” that is whole and entire in each. In this function, all mythologies, all great poetries, and all mystic traditions are in accord. Joseph Campbell What a man believes upon grossly insufficient evidence is an index into his desires -- desires of which he himself is often unconscious. -

2021-2022 MQPCS Handbook

MARY, QUEEN OF PEACE CATHOLIC SCHOOL PARENT/STUDENT HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT MQPCS 4 The School Crest 4 Message to Parents and Students 5 Mission Statement 5 School Beliefs 5 Profile of a Mary, Queen of Peace Student 5 Profile of a Mary, Queen of Peace Parent 6 General Information 6 ADMISSIONS 6 Grading 7 Report Cards/Interims 7 Honor Roll 7 Homework 7 Incomplete Grades 8 Textbooks 8 PROMOTION/RETENTION POLICIES 8 Promotion 8 Retention 8 Multiple Failures 8 Criteria for 7th Grade Graduation 8 Summer School 8 CHRISTIAN SERVICE PROGRAM 8 CURRICULUM 9 PARENT-TEACHER COMMUNICATION AND CONFERENCES 10 Parent - Teacher Communication 10 Procedures for Problem Solving 10 Parent-Teacher Conferences 10 HEALTH AND MEDICAL POLICIES 10 Medication At School 10 Student Sickness/Injury 11 Food Allergies 11 COVID 19 PROCEDURES 11 ATTENDANCE POLICIES 12 Attendance 12 Absences 13 Tardiness 13 ARRIVAL/DISMISSAL POLICIES 13 Page - 1 - Arrival Policies 13 Dismissal Policies 14 Car Line Policies 14 Bus Riders 14 Student Checkout 14 Severe Weather Dismissal Policy 15 Dismissal Procedures for Sports Teams and Cheerleaders 15 CAFETERIA 15 AFTER SCHOOL CARE SERVICES 16 STUDENT DRESS/ SCHOOL UNIFORM 17 MQPCS Uniform 18 Winter Uniform 18 PE Uniform 18 Uniforms for Field Trips 18 Out of Uniform/Spirit Attire 18 Athletic Uniforms 18 Scout Uniforms 18 Hair and Cosmetics 18 Jewelry 19 COUGAR PRIDE: POSITIVE PROGRAMS AND REWARDS 19 Cougar Paws 19 Cougar Prints 19 Peace Pride 19 Spirit Rallies 19 Honor Roll Awards 19 Christian Living Awards 19 STUDENT CONDUCT 20 -

Cougar Town S02 Vostfr

Cougar town s02 vostfr click here to download Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Cougar Town S06E09 VOSTFR HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Chicago Fire S03E02 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 5, 0. Castle S07E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 1, 1. Chicago Fire Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 13, 8. Chicago Fire Saison Cougar Town S05E13 FINAL FRENCH HDTV, Mo, 2, 0. Charmed Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 10, 5 Chicago PD Saison 1 VOSTFR HDTV, Go, 2, 2 Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 4, 2. 24 Heures Chrono - Saison 2 Beverly Hills Nouvelle Génération - Saison 2 A Young Doctor's Notebook - Saison 2 .. Cougar Town - Saison 2. www.doorway.ru season 2 p — omcougar-town-seasonepisode-2 Hosts: Filenuke Movreel Sharerepo www.doorway.ruS04Ep. cougar town s05e09 p-mifydu's blog. www.doorway.rulm. www.doorway.ruilm. www.doorway.rup. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.ru, MB. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.rulm. Routine Her Amazed, Thing in dallas vostfr s02 Little Mansion was my first Sue s02 Dallas vostfr s02 href="www.doorway.ru Season 1, Season 2, Season 3, Season 4. Release Year: In Season 1, Detective Gordon tangles with unsavory crooks and supervillains in Gotham City . Cougar Town Saison 1 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 66, Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 51, 6. Cougar Town S03E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Saison 2 · Liste des épisodes · modifier · Consultez la documentation du modèle. -

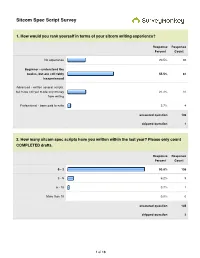

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

The Frontier, November 1932

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 University of Montana Publications 11-1932 The Frontier, November 1932 Harold G. Merriam Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Merriam, Harold G., "The Frontier, November 1932" (1932). The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939. 41. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier/41 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V'«l o P i THE1$III! NOVEMBER, 1932 FRONTIER A MAGAZINt Of THf NORTHWfST THE WEST—A LOST CHAPTER c a r e y McW il l ia m s THE SIXES RUNS TO THE SEA Story by HOWARD McKINLEY CORNING SCOUTING WITH THE U. S. ARMY, 1876-77 J. W. REDINGTON THE RESERVATION JOHN M. KLINE Poems by Jason Bolles, Mary B. Clapp, A . E. Clements, Ethel R. Fuller, G. Frank Goodpasture, Raymond Kresensky, Queene B. Lister, Lydia Littell, Catherine Macleod, Charles Olsen, Lawrence Pratt, Lucy Robinson, Claite A . Thom son, Harold Vinal, Elizabeth Waters, W . A. Ward, Gale Wilhelm, Anne Zuker. O T H E R STO R IE S by Brassil Fitzgerald and Harry Huse. -

HERO SANDWICH Angela Knight Meg Jennings Stepped out Onto The

Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html HERO SANDWICH Angela Knight Meg Jennings stepped out onto the roof of her apartment building, her boots scraping on the concrete. Below, horns honked and an eighteen-wheeler growled in acceleration as a fire truck wailed its way down the street. Restless, she strode to the roof’s edge. All around her, the lights of Manhattan glittered in the darkness as if the stars had showered down to earth. Meg stared downward, brooding. She’d had no choice except to break it off with Richard tonight. Much as she loved him, she couldn’t keep tolerating his secrecy, his habit of disappearing,his evasiveness. She couldn’t even remember the last time they’d actually ended a date without him being called off by some mysterious phone call. Any explanation he’d bothered to give afterward always had the ring of a lie. Meg had lived a double life long enough to recognize the signs in somebody else. She knew what she was doing in hers. She wasn’t at all sure she wanted to know what Richard was doing with his. Maybe he was a hero, risking his life in the pursuit of justice. But there was something about Richard, something just a little bit dark, a little bit ruthless. That sounded more like villain than hero to Meg -- and she wasn’t willing to go down that particular road again. She didn’t like where it led. Even so, the expression on his handsome face when she’d told him it was over had stabbed into her soul. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

Alicia González-Camino Calleja English, French, Italian and German Translator

Alicia González-Camino Calleja English, French, Italian and German translator Born in Madrid, Spain, 1983 Calle General Arrando 32 – 28010 – Madrid +34 649 37 73 75 / +39 3738330526 [email protected] Profile Profile 2001 - 2005 Bachelor’s Degree in Translation and Interpreting Universidad Pontificia Comillas (Madrid) Specialization: conference interpreting 2002 - 2003 Langues Appliquées Étrangères Université Marc Bloch (Strasbourg) Erasmus Grant EDUCATION 2005 Sworn English translator Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation [Exp. nº 3899/lic] 2009 - 2010 Master’s Degree in Dubbing, Translation and Subtitling Universidad Europea de Madrid. Translation and subtitling of cinema and TV scripts, quality control, production and marketing in the dubbing business, videogames and website localization 2011 Quality control trainee: script translations and end product at Disney Character Voices (Madrid) 2010 Quality control internship: script translations and end product in the Disney Dept. at Soundub (Madrid) 2006 Translation internship of legal/technical texts at Romera Translations (Heidelberg, Germany) TRAINING TRAINING Goya-Leonardo Grant EXPERIENCE 2005 Interpreter trainee at the Court of Justice in Madrid 2004 Translation and proofreading internship at McLehm Traductores (Madrid) SPANISH Mother tongue (Castilian) ENGLISH Excellent knowledge ≈CPE Proficiency, Cambridge University 1995-2004 Plymouth (England), Normandy (France) and California (USA) FRENCH Excellent knowledge ≈ Diplôme DALF C2, Alliance Française 2002-2003 -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

Download Ebook ~ the Courteney Cox Handbook

AK3NQU6LZRTJ » Kindle // The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney... Th e Courteney Cox Handbook - Everyth ing you need to know about Courteney Cox Filesize: 6.82 MB Reviews A really awesome ebook with perfect and lucid reasons. Indeed, it is engage in, still an amazing and interesting literature. I am just very easily could possibly get a satisfaction of reading a composed publication. (Petra Kuphal) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 7SLYKHJ8JPUL \\ Doc # The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney... THE COURTENEY COX HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT COURTENEY COX To download The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney Cox PDF, you should refer to the hyperlink under and download the ebook or get access to additional information that are in conjuction with THE COURTENEY COX HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT COURTENEY COX book. tebbo. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 192 pages. Dimensions: 11.6in. x 8.3in. x 0.4in.Courteney Bass Cox (born June 15, 1964) is an American actress best known for her roles as Monica Geller on the NBC sitcom Friends, Gale Weathers in the horror series Scream, and as Jules Cobb in the ABC sitcom Cougar Town, for which she earned her first Golden Globe nomination. Cox has also starred in Dirt produced by Coquette Productions, a production company created by herself and husband David Arquette. This book is your ultimate resource for Courteney Cox. Here you will find the most up-to-date information, photos, and much more. In easy to read chapters, with extensive references and links to get you to know all there is to know about her Early life, Career and Personal life right away. -

La Posmodernidad Analiza La Sitcom: Community

La Posmodernidad Analiza la Sitcom: Community Autor /a: Jaime Costas Nicolás Profesor/a: Iván Pintor Encrucijadas contemporáneas entre cine, televisión y cómic, primer trimestre, 2013-2014 Facultat de Comunicación Universitat Pompeu Fabra Resum / Resumen: Mucho se ha escrito sobre la relación entre posmodernismo y la sitcom Community. En el presente ensayo, a través del análisis de dos de sus episodios, no sólo se constata esta relación sino que se postula que en el centro argumental de la serie y en los engranajes que la hacen funcionar se encuentra la propia idea de posmodernismo y las diversas técnicas que han identificado este movimiento cultural. Paraules clau / Palabras clave: · Posmodernismo Community intertextualidad metaficción Abstract: Much has been written about the relationship between the situational comedy Community and postmodernism. In this essay, through the analysis of two of its episodes, we not only reassure this connection but we also argue that the narrative center of the show and the engines that make it move forward are the idea of postmodernism itself and the different techniques that have defined this cultural movement. Keywords: Postmodernism Community intertextuality metafiction La posmodernidad analiza la sitcom: Community En esta última década, la ficción televisiva está viviendo uno de sus mejores momentos en cuanto a calidad y variedad, gracias a una mayor complejidad narrativa o el uso de nuevas formas y géneros. Ya en los años noventa nos encontramos con los primeros indicios de esta explosión cualitativa, de ahí el nombre Quality TV, que vendría más adelante, con ficciones como la lynchiana Twin Peaks (1990 - 1991) o el archiconocido caso de la comedia que no trataba sobre nada, Seinfeld (1989 - 1998). -

89 Geo. Wash. L. Rev

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\89-4\GWN402.txt unknown Seq: 1 8-JUL-21 10:48 Title IX, Esports, and #EToo Jane K. Stoever* ABSTRACT As colleges and universities increasingly award video gaming scholar- ships, field competitive esports teams, construct esports arenas in the centers of campuses, and promote student interaction through gaming, schools should anticipate the sexual cyberviolence, harassment, and technology-enabled abuse that commonly occur through gaming. This Article is the first to examine Title IX and First Amendment implica- tions of schools promoting and sponsoring gaming. To date, the rare Title IX discussion concerning esports has focused on increasing female representation in this male-dominated realm. As campuses invest heavily in esports, they also should foresee that funding and promoting esports—without attending to gen- der-based harassment and sexual violence in games and gaming—could lead to concerns that college campuses and organizational climates signal tolerance of sexual harassment and create “chilly” climates conducive to underreporting and retaliation. Colleges instead could lead in creating safe and inclusive gam- ing experiences. Esports is one of the fastest growing competitive markets in the world, and the gaming industry is repeating past mistakes of professional sports leagues like the National Football League, as demonstrated through the sum- mer 2020 outpouring of allegations of gender-based harassment, discrimina- tion, and sexual assault from competitive gamers and streamers. Rather than waiting for a global #EToo movement to create demand for a comprehensive gender-based violence policy, colleges should affirmatively act to create re- sponsible gaming initiatives with goals of violence prevention, player protec- tion, and harm minimization.