Alexandria Hub of the Hellenistic World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legionary Philip Matyszak

LEGIONARY PHILIP MATYSZAK LEGIONARY The Roman Soldier’s (Unofficial) Manual With 92 illustrations To John Radford, Gunther Maser and the others from 5 Group, Mrewa. Contents Philip Matyszak has a doctorate in Roman history from St John’s College, I Joining the Roman Army 6 Oxford, and is the author of Chronicle of the Roman Republic, The Enemies of Rome, The Sons of Caesar, Ancient Rome on Five Denarii a Day and Ancient Athens on Five Drachmas a Day. He teaches an e-learning course in Ancient II The Prospective Recruit’s History for the Institute of Continuing Education at Cambridge University. Good Legion Guide 16 III Alternative Military Careers 33 HALF-TITLE Legionary’s dagger and sheath. Daggers are used for repairing tent cords, sorting out boot hobnails and general legionary maintenance, and consequently see much more use than a sword. IV Legionary Kit and Equipment 52 TITLE PAGE Trajan addresses troops after battle. A Roman general tries to be near the front lines in a fight so that he can personally comment afterwards on feats of heroism (or shirking). V Training, Discipline and Ranks 78 VI People Who Will Want to Kill You 94 First published in the United Kingdom in 2009 by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London wc1v 7qx VII Life in Camp 115 First paperback edition published in 2018 Legionary © 2009 and 2018 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London VIII On Campaign 128 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording IX How to Storm a City 149 or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

The History of Egypt Under the Ptolemies

UC-NRLF $C lb EbE THE HISTORY OF EGYPT THE PTOLEMIES. BY SAMUEL SHARPE. LONDON: EDWARD MOXON, DOVER STREET. 1838. 65 Printed by Arthur Taylor, Coleman Street. TO THE READER. The Author has given neither the arguments nor the whole of the authorities on which the sketch of the earlier history in the Introduction rests, as it would have had too much of the dryness of an antiquarian enquiry, and as he has already published them in his Early History of Egypt. In the rest of the book he has in every case pointed out in the margin the sources from which he has drawn his information. » Canonbury, 12th November, 1838. Works published by the same Author. The EARLY HISTORY of EGYPT, from the Old Testament, Herodotus, Manetho, and the Hieroglyphieal Inscriptions. EGYPTIAN INSCRIPTIONS, from the British Museum and other sources. Sixty Plates in folio. Rudiments of a VOCABULARY of EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS. M451 42 ERRATA. Page 103, line 23, for Syria read Macedonia. Page 104, line 4, for Syrians read Macedonians. CONTENTS. Introduction. Abraham : shepherd kings : Joseph : kings of Thebes : era ofMenophres, exodus of the Jews, Rameses the Great, buildings, conquests, popu- lation, mines: Shishank, B.C. 970: Solomon: kings of Tanis : Bocchoris of Sais : kings of Ethiopia, B. c. 730 .- kings ofSais : Africa is sailed round, Greek mercenaries and settlers, Solon and Pythagoras : Persian conquest, B.C. 525 .- Inarus rebels : Herodotus and Hellanicus : Amyrtaus, Nectanebo : Eudoxus, Chrysippus, and Plato : Alexander the Great : oasis of Ammon, native judges, -

The Story of Osiris Osiris Was the King of Egypt

Story The Story of Osiris Osiris was the King of Egypt. During his reign, Osiris’ people were happy and well-fed. However, Osiris’ brother Seth became very jealous of the king’s success. While Osiris was travelling and bringing his blessings to other nations, Seth came up with a devious plan. Secretly, Seth found out Osiris’ exact body measurements and asked for a beautiful chest to be made that he knew would only fit Osiris. Upon Osiris’ return from his travels, Seth invited his brother to a great feast. During the celebrations, Seth revealed the exquisite chest and declared that he would give it to anyone who fitted into it exactly. Many tried and failed to fit into the chest, and eventually, Osiris asked to try. He was delighted that the chest fitted him perfectly, but at that very moment, Seth’s evil plan revealed itself; he slammed the lid, nailed it shut and sealed every crack with molten lead. Osiris died within the chest and his soul (or ‘ka’) moved on into the spirit world. Seth ruthlessly cast the chest that contained Osiris’ body into the River Nile. Isis, who was Osiris’ sister and wife, was devastated and feared for the safety of Horus, their child. She secretly fled into the marshes to look after Horus but was afraid that Seth would find the baby and murder him. So when Isis found shelter on a small, isolated island, which was home to the goddess Buto, she asked Buto to guard Horus. For extra protection, Isis transformed the island into a floating island, so it never stayed in one place permanently. -

Aaaaannual Review

AAAAAnnual Review Front Cover: The Staffordshire Hoard (see page 27) Reproduced by permission of Birmingham Museum and Art Galleries See www.staffordshirehoard.org.uk Back Cover: Cluster of Quartz Crystals (see page 23) Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society Annual Report and Review 2010 th The 190 Annual Report of the Council at the close of the session 2009-10 Presented to the Annual Meeting held on 8th December 2010 and review of events and grants awarded THE LEEDS PHILOSOPHICAL AND LITERARY SOCIETY, founded in 1819, has played an important part in the cultural life of Leeds and the region. In the nineteenth century it was in the forefront of the intellectual life of the city, and established an important museum in its own premises in Park Row. The museum collection became the foundation of today’s City Museum when in 1921 the Society transferred the building and its contents to the Corporation of Leeds, at the same time reconstituting itself as a charitable limited company, a status it still enjoys today. Following bomb damage to the Park Row building in the Second World War, both Museum and Society moved to the City Museum building on The Headrow, where the Society continued to have its offices until the museum closed in 1998. The new Leeds City Museum, which opened in 2008, is now once again the home of the Society’s office. In 1936 the Society donated its library to the Brotherton Library of the University of Leeds, where it is available for consultation. Its archives are also housed there. The official charitable purpose of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society is (as newly defined in 1997) “To promote the advancement of science, literature and the arts in the City of Leeds and elsewhere, and to hold, give or provide for meetings, lectures, classes, and entertainments of a scientific, literary or artistic nature”. -

Perceptions of the Ancient Jews As a Nation in the Greek and Roman Worlds

Perceptions of the Ancient Jews as a Nation in the Greek and Roman Worlds By Keaton Arksey A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Classics University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2016 by Keaton Arksey Abstract The question of what made one Jewish in the ancient world remains a fraught topic for scholars. The current communis opinio is that Jewish communities had more in common with the Greeks and Romans than previously thought. Throughout the Diaspora, Jewish communities struggled with how to live amongst their Greco-Roman majority while continuing to practise their faith and thereby remain identifiably ‘Jewish’. To describe a unified Jewish identity in the Mediterranean in the period between 200 BCE and 200 CE is incorrect, since each Jewish community approached its identity in unique ways. These varied on the basis of time, place, and how the non-Jewish population reacted to the Jews and interpreted Judaism. This thesis examines the three major centres of Jewish life in the ancient world - Rome, Alexandria in Egypt, and Judaea - demonstrate that Jewish identity was remarkably and surprisingly fluid. By examining the available Jewish, Roman, and Greek literary and archaeological sources, one can learn how Jewish identity evolved in the Greco-Roman world. The Jews interacted with non-Jews daily, and adapted their neighbours’ practices while retaining what they considered a distinctive Jewish identity. Each chapter of this thesis examines a Jewish community in a different region of the ancient Mediterranean. -

Naukratis, Heracleion-Thonis and Alexandria

Originalveröffentlichung in: Damian Robinson, Andrew Wilson (Hg.), Alexandria and the North-Western Delta. Joint conference proceedings of Alexandria: City and Harbour (Oxford 2004) and The Trade and Topography of Egypt's North-West Delta, 8th century BC to 8th century AD (Berlin 2006), Oxford 2010, S. 15-24 2: Naukratis, Heracleion-Thonis and Alexandria - Remarks on the Presence and Trade Activities of Greeks in the North-West Delta from the Seventh Century BC to the End of the Fourth Century BC Stefan Pfeiffer The present article examines how Greek trade in Egypt 2. Greeks and SaTtic Egypt developed and the consequences that the Greek If we disregard the Minoan and Mycenaean contacts economic presence had on political and economic condi with Egypt, we can establish Greco-Egyptian relations as tions in Egypt. I will focus especially on the Delta region far back as the seventh century BC.2 A Greek presence and, as far as possible, on the city of Heracleion-Thonis on in the Delta can be established directly or indirectly for the Egyptian coast, discovered by Franck Goddio during the following places: Naukratis, Korn Firin, Sais, Athribis, underwater excavations at the end of the twentieth Bubastis, Mendes, Tell el-Mashkuta, Daphnai and century. The period discussed here was an exceedingly Magdolos. 3 In most of the reports, 4 Rhakotis, the settle exciting one for Egypt, as the country, forced by changes ment preceding Alexandria, is mentioned as the location in foreign policy, reversed its isolation from the rest of the of the Greeks, an assumption based on a misinterpreted ancient world. -

Comments to the Lithic Industry of the Buto-Maadi Culture in Lower Egypt

ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE AND HUMAN CULTURE IN THE NILE BASIN AND NORTHERN AFRICA UNTIL THE SECOND MILLENNIUM B.C. Poznari 1993 PL ISSN 0866-9244 ISBN 83-900434-1-6 Klaus Schmidt Comments to the lithic industry of the Buto-Maadi culture in Lower Egypt New investigation of the Predynastic cultures of Lower Egypt - for a long time only known from short preliminary reports of old excavations - now allow a better understanding of the period in this region. The excavations at Merimde- Benisalame (Eiwanger 1984; 1988) and Tell el-Fara'in (von der Way 1986; 1987; 1988; 1989), the historical Buto, as well as re-examination of old excavation finds from el-Omari (Debono and Mortensen 1990), Heliopolis (Debono and Morten- sen 1988) and Maadi (Rizkana and Seeher 1984; 1985; 1987; 1988) have changed the situation. Today the prehistory of Lower Egypt is better known than that of Upper Egypt. In addition to pottery, normally used in “classicaT' comparative studies, now in Lower Egypt exists the possibility for comparisons in lithics. The investigations of Upper Egyptian lithic samples, especially the reassessment of old material are restricted by the absence of good stratigraphic sequences (McHugh 1982: 85; Holmes 1988)). The continuing excavation at Tell el-Fara'in (Buto) present, after Merimde, a chronologically extended stratigraphic sequence of different cultural layers: starting with the period of Maadi (layer I) the stratigraphy at Buto continues into the Early Dynastic Period (layer V) without any visible hiatus (von der Way 1989). Now we are able to recognize that the Maadi culture is not a local phenomenon, but distributed over the whole Delta with some additional smaller sites south of Cairo (Habachi and Kaiser 1985; Kaiser 1985; Mortensen 1985; Junker 1912: 2). -

The Jewish Context of Early Church History ROMAN CHURCH *KEY AD EMPEROR YEAR EVENT 26 TIBERIUS 27

The Jewish Context Of Early Church History ROMAN CHURCH *KEY AD EMPEROR YEAR EVENT 26 TIBERIUS -7 {Sabbatical} th 27 (14 ) -6 [Year 1 of Daniel’s 70 th Sabbatical Cycle Begins In Fall ] th 28 (15 ) -5 [Year 2 of Daniel’s 70th Sabbatical Cycle Begins In Fall ] *John began immersing in the Spring. th 29 (16 ) -4 [Year 3 of Daniel’s 70 th Sabbatical Cycle Begins In Fall ] *Jesus was immersed in the Fall. th 30 (17 ) -3 [Year 4 of Daniel’s 70 th Sabbatical Cycle Begins In Fall ] *Jesus began preaching in the Spring. th 31 (18 ) -2 [Year 5 of Daniel’s 70 th Sabbatical Cycle Begins In Fall ] th 32 (19 ) -1 [Year 6 of Daniel’s 70 th Sabbatical Cycle Begins In Fall ] th 33 (20 ) 1 {Sabbatical} [Year 7 of Daniel’s 70 th Sabbatical Cycle Begins In Fall ] *THE ATONEMENT 34 (21 st ) 2 *Saul of Tarsus took the lead in persecuting “The Way.” 35 (22 nd ) 3 *Saul of Tarsus was converted at Damascus, easing the persecution. 36 (23 rd ) 4 *The book of James was written around this time.1 37 GAIUS 5 38 (2 nd ) 6 *Peter preaches to Gentiles for the 1 st Time around this time. 39 (3 rd ) 7 th 2 40 (4 ) 8 {Sabbatical} *Gaius tried to have his image set up in the Jewish Temple. 41 CLAUDIUS 9 42 (2 nd ) 10 *Barnabas sent to oversee the predominately Gentile Church at Antioch. 43 (3 rd ) 11 *Saul of Tarsus works with Barnabas at Antioch. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Sidirountios3

ZEALOT EARLY CHRISTIANITY AND THE EMERGENCE OF ANTI‑ HELLENISM GEORGE SIDIROUNTIOS A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London (Royal Holloway and Bedford New College) March 2016 1 Candidate’s declaration: I confirm that this PhD thesis is entirely my own work. All sources and quotations have been acknowledged. The main works consulted are listed in the bibliography. Candidate’s signature: 2 To the little Serene, Amaltheia and Attalos 3 CONTENTS Absract p. 5 Acknowledgements p. 6 List of Abbreviations p. 7 Conventions and Limitations p. 25 INTRODUCTION p. 26 1. THE MAIN SOURCES 1.1: Lost sources p. 70 1.2: A Selection of Christian Sources p. 70 1.3: Who wrote which work and when? p. 71 1.4: The Septuagint that contains the Maccabees p. 75 1.5: I and II Maccabees p. 79 1.6: III and IV Maccabees p. 84 1.7: Josephus p. 86 1.8: The first three Gospels (Holy Synopsis) p. 98 1.9: John p. 115 1.10: Acts p. 120 1.11: ʺPaulineʺ Epistles p. 123 1.12: Remarks on Paulʹs historical identity p. 126 2. ISRAELITE NAZOREAN OR ESSENE CHRISTIANS? 2.1: Israelites ‑ Moses p. 136 2.2: Israelite Nazoreans or Christians? p. 140 2.3: Essenes or Christians? p. 148 2.4: Holy Warriors? p. 168 3. ʺBCE CHRISTIANITYʺ AND THE EMERGENCE OF ANTI‑HELLENISM p. 173 3.1: A first approach of the Septuagint and ʺJosephusʺ to the Greeks p. 175 3.2: Anti‑Hellenism in the Septuagint p. 183 3.3: The Maccabees and ʺJosephusʺ from Mattathias to Simon p. -

ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 5-2011 ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Emerson T. Brooking University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Military History Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Brooking, Emerson T., "ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72" 01 May 2011. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145 For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Abstract This study evaluates the military history and practice of the Roman Empire in the context of contemporary counterinsurgency theory. It purports that the majority of Rome’s security challenges fulfill the criteria of insurgency, and that Rome’s responses demonstrate counterinsurgency proficiency. These assertions are proven by means of an extensive investigation of the grand strategic, military, and cultural aspects of the Roman state. Fourteen instances of likely insurgency are identified and examined, permitting the application of broad theoretical precepts -

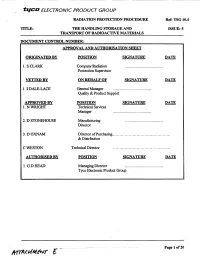

The Handling Storage and Transport

tiicA ELECTRONIC PRODUCT GROUP RADIATION PROTECTION PROCEDURE Ref: TSG 10.4 TITLE: THE HANDLING STORAGE AND ISSUE: 5 TRANSPORT OF RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS DOCUMENT CONTROL NUMBER: APPROVAL AND AUTHORISATION SHEET ORIGINATED BY POSITION SIGNATURE DA.TE 1. S CLARK Company Radiation Protection Supervisor VETTED BY ON BEHALF OF SIGNATURE DA ,TE 1. 1 DALE-LACE General Manager Quality & Product Support APPROVED BY POSITION SIGNATURE DAITE 1. N WRIGHT Technical Services Manager 2. D STONEHOUSE Manufacturing Director 3. D OXNAM Director of Purchasing ............................................ & Distribution C WESTON Technical Director AUTHORISED BY POSION SIGNATURE DA,TE 1. GD HEAD M anaging D irector ........................................ Tyco Electronic Product Group Page 1 of 20 -."+ c. .A .r. tZIca ELECTRONIC PRODUCT GROUP RADIATION PROTECTI(4• PROCEDURE Ref: TSG 10.4 TITLE: THE HANDLING STORAGE AND ISSUE: 5 TRANSPORT OF RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS CONTENTS LIST 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Scope 3.0 Responsibilities 4.0 Definitions 5.0 Procedure 5.1 Equipment & Materials 5.2 Health & Safety 5.2.1 Incident Reporting Procedure 5.3 Procedure 5.3.1 Despatch & Return of Finished Goods & Service Detectors to UK Destinations 5.3.2 Despatch of sample MF/Raft Detectors to UK destinations 5.3.3 Despatch of Finished Goods to International destinations 5.3.4 Packaging & Despatch of Waste (Scrap) or Detectors within UK 5.3.4.1 Removal from Customers Premises (all types) 5.3.4.2 Damaged Detectors (all types) 5.3.4.3 Packaging - Excepted 5.3.4.4 Packaging - I White,