Assays from the History of Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff This study appears as part III of Toumanoff's Studies in Christian Caucasian History (Georgetown, 1963), pp. 277-354. An earlier version appeared in the journal Le Muséon 72(1959), pp. 1-36 and 73(1960), pp. 73-106. The Orontids of Armenia Bibliography, pp. 501-523 Maps appear as an attachment to the present document. This material is presented solely for non-commercial educational/research purposes. I 1. The genesis of the Armenian nation has been examined in an earlier Study.1 Its nucleus, succeeding to the role of the Yannic nucleus ot Urartu, was the 'proto-Armenian,T Hayasa-Phrygian, people-state,2 which at first oc- cupied only a small section of the former Urartian, or subsequent Armenian, territory. And it was, precisely, of the expansion of this people-state over that territory, and of its blending with the remaining Urartians and other proto- Caucasians that the Armenian nation was born. That expansion proceeded from the earliest proto-Armenian settlement in the basin of the Arsanias (East- ern Euphrates) up the Euphrates, to the valley of the upper Tigris, and espe- cially to that of the Araxes, which is the central Armenian plain.3 This expand- ing proto-Armenian nucleus formed a separate satrapy in the Iranian empire, while the rest of the inhabitants of the Armenian Plateau, both the remaining Urartians and other proto-Caucasians, were included in several other satrapies.* Between Herodotus's day and the year 401, when the Ten Thousand passed through it, the land of the proto-Armenians had become so enlarged as to form, in addition to the Satrapy of Armenia, also the trans-Euphratensian vice-Sa- trapy of West Armenia.5 This division subsisted in the Hellenistic phase, as that between Greater Armenia and Lesser Armenia. -

Defusing Conflict in Tsalka District of Georgia: Migration, International Intervention and the Role of the State

Defusing Conflict in Tsalka District of Georgia: Migration, International Intervention and the Role of the State Jonathan Wheatley ECMI Working Paper #36 October 2006 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES (ECMI) Schiffbruecke 12 (Kompagnietor) D-24939 Flensburg Germany +49-(0)461-14 14 9-0 fax +49-(0)461-14 14 9-19 internet: http://www.ecmi.de ECMI Working Paper #36 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Director: Dr. Marc Weller Copyright 2006 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Published in October 2006 by the European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) ISSN: 1435-9812 2 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................................... 4 II. TSALKA DISTRICT: AN OVERVIEW................................................................................................................... 5 ECONOMY AND INFRASTRUCTURE .................................................................................................................................. 5 DEMOGRAPHY AND MIGRATION ..................................................................................................................................... 8 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS AND THE ROLE OF THE STATE........................................................................................... 11 III. MAIN ARENAS OF CONFLICT IN TSALKA DISTRICT................................................................................ 14 INTER-COMMUNAL CONFLICT AT LOCAL LEVEL -

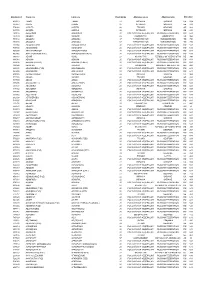

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

Georgian Polyphony in a Century of Research: Foreword from the Editors

In: Echoes from Georgia: Seventeen Arguments on Georgian Polyphony. Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Joseph Jordania (Eds.). New York: Nova Science, 2010: xvii-xxii GEORGIAN POLYPHONY IN A CENTURY OF RESEARCH: FOREWORD FROM THE EDITORS Joseph Jordania and Rusudan Tsurtsumia This collection represents some of the most important authors and their writings about Georgian traditional polyphony for the last century. The collection is designed to give the reader the most possibly complete picture of the research on Georgian polyphony. Articles are given in a chronological order, and the original year of the publication (or completing the work) is given at every entry. As the article of Simha Arom and Polo Vallejo gives the comprehensive review of the whole collection, we are going instead to give a reader more general picture of research directions in the studies of Georgian traditional polyphony. We can roughly divide the whole research activities about Georgian traditional polyphony into six periods: (1) before the 1860s, (2) from the 1860s to 1900, (3) from the 1900s to 1930, (4) from the 1930s to 1950, (5) from the 1950s to 1990, and (6) from the 1990s till today. The first period (which lasted longest, which is usual for many time-based classifications), covers the period before the 1860s. Two important names from Georgian cultural history stand out from this period: Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani (17th-18th centuries), and Ioane Bagrationi (beginning of the 18th-19th centuries). Both of them were highly educated people by the standards of their time. Ioane Bagrationi (1768-1830), known also as Batonishvili (lit. “Prince”) was the heir of Bagrationi dynasty of Georgian kings. -

River Systems and Their Water and Sediment Fluxes Towards the Marine Regions of the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea Earth System: an Overview

Review Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.19514 River systems and their water and sediment fluxes towards the marine regions of the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea earth system: An overview Serafeim E. POULOS Laboratory of Physical Geography, Section of Geography & Climatology, Department of Geology & Geoenvironment, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis-Zografou, 10584, Attiki Corresponding author: [email protected] Handling Editor: Argyro ZENETOS Received: 22 January 2019; Accepted: 6 July 2019; Published on line: 5 September 2019 Abstract A quantitative assessment of the riverine freshwater, suspended and dissolved sediment loads is provided for the watersheds of the four primary (Western Mediterranean-WMED, Central Mediterranean-CMED, Eastern Mediterranean-EMED and Black Sea- BLS) and eleven secondary marine regions of the Mediterranean and Black Sea Earth System (MBES). On the basis of measured values that cover spatially >65% and >84% of MED and BLS watersheds, respectively, water discharge of the MBES reaches annually almost the 1 million km3, with Mediterranean Sea (including the Marmara Sea) providing 576 km3 and the Black Sea (included the Azov Sea) 418 km3. Among the watersheds of MED primary marine regions, the total water load is distributed as follows: WMED= 180 km3; CMED= 209 km3; and EMED= 187 km3. The MBES could potentially provide annually some 894 106 t of suspended sediment load (SSL), prior to river damming, most of which (i.e., 708 106 t is attributed to MED). -

Annexation of Georgia in Russian Empire

1 George Anchabadze HISTORY OF GEORGIA SHORT SKETCH Caucasian House TBILISI 2005 2 George Anchabadze. History of Georgia. Short sketch Above-mentioned work is a research-popular sketch. There are key moments of the history of country since ancient times until the present moment. While working on the sketch the author based on the historical sources of Georgia and the research works of Georgian scientists (including himself). The work is focused on a wide circle of the readers. გიორგი ანჩაბაძე. საქართველოს ისტორია. მოკლე ნარკვევი წინამდებარე ნაშრომი წარმოადგენს საქართველოს ისტორიის სამეცნიერ-პოპულარულ ნარკვევს. მასში მოკლედაა გადმოცემული ქვეყნის ისტორიის ძირითადი მომენტები უძველესი ხანიდან ჩვენს დრომდე. ნარკვევზე მუშაობისას ავტორი ეყრდნობოდა საქართველოს ისტორიის წყაროებსა და ქართველ მეცნიერთა (მათ შორის საკუთარ) გამოკვლევებს. ნაშრომი განკუთვნილია მკითხველთა ფართო წრისათვის. ISBN99928-71-59-8 © George Anchabadze, 2005 © გიორგი ანჩაბაძე, 2005 3 Early Ancient Georgia (till the end of the IV cen. B.C.) Existence of ancient human being on Georgian territory is confirmed from the early stages of anthropogenesis. Nearby Dmanisi valley (80 km south-west of Tbilisi) the remnants of homo erectus are found, age of them is about 1,8 million years old. At present it is the oldest trace in Euro-Asia. Later on the Stone Age a man took the whole territory of Georgia. Former settlements of Ashel period (400–100 thousand years ago) are discovered as on the coast of the Black Sea as in the regions within highland Georgia. Approximately 6–7 thousands years ago people on the territory of Georgia began to use as the instruments not only the stone but the metals as well. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Report, on Municipal Solid Waste Management in Georgia, 2012

R E P O R T On Municipal Solid Waste Management in Georgia 2012 1 1 . INTRODUCTION 1.1. FOREWORD Wastes are one of the greatest environmental chal- The Report reviews the situation existing in the lenges in Georgia. This applies both to hazardous and do- field of municipal solid waste management in Georgia. mestic wastes. Wastes are disposed in the open air, which It reflects problems and weak points related to munic- creates hazard to human’s health and environment. ipal solid waste management as related to regions in Waste represents a residue of raw materials, semi- the field of collection, transportation, disposal, and re- manufactured articles, other goods or products generat- cycling. The Report also reviews payments/taxes re- ed as a result of the process of economic and domestic lated to the waste in the country and, finally, presents activities as well as consumption of different products. certain recommendations for the improvement of the As for waste management, it generally means distribu- noted field. tion of waste in time and identification of final point of destination. It’s main purpose is reduction of negative impact of waste on environment, human health, or es- 1.2. Modern Approaches to Waste thetic condition. In other words, sustainable waste man- Management agement is a certain practice of resource recovery and reuse, which aims to the reduction of use of natural re- The different waste management practices are ap- sources. The concept of “waste management” includes plied to different geographical or geo-political locations. the whole cycle from the generation of waste to its final It is directly proportional to the level of economic de- disposal. -

Abhazya/Gürcistan: Tarih – Siyaset – Kültür

TÜR L Ü K – CEMAL GAMAKHARİA LİA AKHALADZE T ASE Y Sİ – H ARİ T : AN T S Cİ R A/GÜ Y ABHAZ ZE D İA AKHALA İA L İA İA R ABHAZYA/GÜRCİSTAN: ,6%1 978-9941-461-51-4 L GAMAKHA L TARİH – SİYASET – KÜLTÜR CEMA 9 7 8 9 9 4 1 4 6 1 5 1 4 CEMAL GAMAKHARİ A Lİ A AKHALADZE ABHAZYA/GÜRCİ STAN: TARİ H – Sİ YASET – KÜLTÜR Tiflis - İ stanbul 2016 UDC (uak) 94+32+008)(479.224) G-16 Yayın Kurulu: Teimuraz Mjavia (Editör), Prof. Dr. Roin Kavrelişvili, Prof. Dr. Erdoğan Altınkaynak, Prof. Dr. Rozeta Gujejiani, Giorgi Iremadze. Gürcüce’den Türkçe’ye Prof. Dr. Roin Kavrelişvili tarafından tercüme edil- miştir. Bu kitapta Gürcistan’ın Özerk Cumhuriyeti Abhazya’nın etno-politik tarihi üzerine dikkat çekilmiş ve bu bölgede bulunan kadim Hıristiyan kül- türüne ait ana esaslar ile ilgili genel görüşler ortaya konulmuştur. Etnik, siyasi ve kültürel açıdan bakıldığında, Abhazya’nın günümüzde sahip olduğu toprakların, tarihin eski dönemlerinden bu yana Gürcü bölgesi olduğu ve bölgede gerçekleşen demografik değişiklilerin ancak Orta Çağın son dönemlerinde gerçekleştiği anlaşılmaktadır. Bu kitabın yazarları 1992 – 1993 yılları arasında Rusya tarafından Gürcistan’a karşı girişilen hibrid savaşlardan ve 2008’de gerçekleştirilen açık saldırganlıktan bahsetmektedirler. Burada, savaştan sonra meydana gelen insani felaketler betimlenmiş, Abhazya’nın işgali ile Avrupa- Atlantik sahasına karşı yapılan hukuksuz jeopolitik gelişmeler anlatılmış ve uluslararası kuruluşların katılımıyla Abhazya’da sürekli ortaya çıkan çatışmaların barışçıl bir yol ile çözülmesinin gerekliliği üzerinde durulmuştur. Düzenleme Levan Titmeria ISBN 978-9941-461-51-4 İçindekiler Giriş (Prof. Dr. Cemal Gamakharia) ..................................... 5 1. -

Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) by Dr

UDC 9 (479.22) 34 Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) by Dr. Levan Z. Urushadze (Tbilisi, Georgia) ISBN 99940-0-539-1 The Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG. “Sakartvelos Demokratiuli Respublika” in Georgian) was the first modern establishment of a Republic of Georgia in 1918 - 1921. The DRG was established after the collapse of the Russian Tsarist Empire that began with the Russian Revolution of 1917. Its established borders were with Russia in the north, and the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in the south. It had a total land area of roughly 107,600 km2 (by comparison, the total area of today's Georgia is 69,700 km2), and a population of 2.5 million. As today, its capital was Tbilisi and its state language - Georgian. THE NATIONAL FLAG AND COAT OF ARMS OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA A Trans-Caucasian house of representatives convened on February 10, 1918, establishing the Trans-Caucasian Democratic Federative Republic, which existed from February, 1918 until May, 1918. The Trans-Caucasian Democratic Federative Republic was managed by the Trans-Caucasian Commissariat chaired by representatives of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia. On May 26, 1918 this Federation was abolished and Georgia declared its independence. Politics In February 1917, in Tbilisi the first meeting was organised concerning the future of Georgia. The main organizer of this event was an outstanding Georgian scientist and public benefactor, Professor Mikheil (Mikhako) Tsereteli (one of the leaders of the Committee -

CJSS Second Issue:CJSS Second Issue.Qxd

Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences The University of Georgia 2009 Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences UDC(uak)(479)(06) k-144 3 Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences EDITOR IN CHIEF Julieta Andghuladze EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Raupp Batumi International University Giuli Alasania The University of Georgia Janette Davies Oxford University Ken Goff The University of Georgia Kornely Kakachia Associate Professor Michael Vickers The University of Oxford Manana Sanadze The University of Georgia Mariam Gvelesiani The University of Georgia Marina Meparishvili The University of Georgia Mark Carper The University of Alaska Anchorage Natia Kaladze The University of Georgia Oliver Reisner The Humboldt University Sergo Tsiramua The University of Georgia Tamar Lobjanidze The University of Georgia Tamaz Beradze The University of Georgia Timothy Blauvelt American Councils Tinatin Ghudushauri The University of Georgia Ulrica Söderlind Stockholm University Vakhtang Licheli The University of Georgia 4 Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences Printed at The University of Georgia Copyright © 2009 by the University of Georgia. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or any means, electornic, photocopinying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of The University of Georgia Press. No responsibility for the views expressed by authors in the Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences is assumed by the editors or the publisher. Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences is published annually by The University -

Public Defender of Georgia

2018 The Public Defender of Georgia www.ombudsman.ge 1 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GEORGIA, 2018 This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. 2 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GEORGIA THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS IN GEORGIA 2018 2018 www.ombudsman.ge www.ombudsman.ge 3 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GEORGIA, 2018 OFFICE OF PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GEORGIA 6, Ramishvili str, 0179, Tbilisi, Georgia Tel: +995 32 2913814; +995 32 2913815 Fax: +995 32 2913841 E-mail: [email protected] 4 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................................13 1. FULFILMENT OF THE RECOMMENDATIONS MADE BY THE PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GEORGIA IN THE 2017 PARLIAMENTARY REPORT ......................................................................19 2. RIGHT TO LIFE .....................................................................................................................................28 2.1. CASE OF TEMIRLAN MACHALIKASHVILI .............................................................................21 2.2. MURDER OF JUVENILES ON KHORAVA STREET ...............................................................29 2.3. OUTCOMES OF THE STUDY OF THE CASE-FILES OF THE INVESTIGATION CONDUCTED ON THE ALLEGED MURDER OF ZVIAD GAMSAKHURDIA, THE FIRST