National Report on the State of the Environment of Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Genetic Characteristic of Dinucleotide Microsatellite Loci in Parthenogenetic Lizards Darevskia Unisexualis A

ISSN 1022-7954, Russian Journal of Genetics, 2009, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 203–210. © Pleiades Publishing, Inc., 2009 Original Russian Text © A.V. Omelchenko, V.I. Korchagin, G.A. Sevast’yanova, A.P. Ryskov, O.N. Tokarskaya, 2009, published in Genetika, 2009, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 230–238. ANIMAL GENETICS Molecular Genetic Characteristic of Dinucleotide Microsatellite Loci in Parthenogenetic Lizards Darevskia unisexualis A. V. Omelchenkoa,b, V. I. Korchagina, G. A. Sevast’yanovab, A. P. Ryskova, and O. N. Tokarskayaa aInstitute of Gene Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119334 Russia; e-mail: [email protected] bMoscow Pedagogical State Univrsity, Moscow, 119882 Russia; e-mail: [email protected] Received April 14, 2008; in final form, July 30, 2008 Abstract—In the present study, the first molecular genetic investigation of dinucleotide (GT)n microsatellite loci in parthenogenetic lizards Darevskia unisexualis was performed. New polymorphic locus, Du214, (GenBank Ac. No. EU252542) was identified and characterized in detail. It was demonstrated that allele of this locus differed in the size and structure of microsatellite locus, as well as in point mutations, the combinations of which enabled the isola- tion of stabile fixed double nucleotide substitutions A–A (alleles 2 and 4) and G–T (alleles 1, 3, 5, and 6). Double nucleotide substitutions described were also identified in the orthlogous loci of the parental species genomes, D. rad- dei (G–T) and D. valentine (A–A). Based on the analysis of allele distribution pattern at this locus in all populations of parthenospecies D. unisexualis, mathematic model was elaborated and realized. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

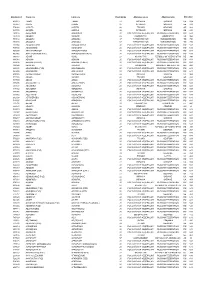

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

Darevskia Raddei and Darevskia Portschinskii) May Not Lead to Hybridization Between Them

Zoologischer Anzeiger 288 (2020) 43e52 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Zoologischer Anzeiger journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jcz Research paper Syntopy of two species of rock lizards (Darevskia raddei and Darevskia portschinskii) may not lead to hybridization between them * Eduard Galoyan a, b, , Viktoria Moskalenko b, Mariam Gabelaia c, David Tarkhnishvili c, Victor Spangenberg d, Anna Chamkina b, Marine Arakelyan e a Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, 33 Leninskij Prosp. 119071, Moscow, Russia b Zoological Museum, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia c Center of Biodiversity Studies, Institute of Ecology, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia d Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia e Department of Zoology, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, Armenia article info abstract Article history: The two species of rock lizards, Darevsia raddei and Darevskia portschinskii, belong to two different Received 19 February 2020 phylogenetic clades of the same genus. They are supposed ancestors for the hybrid parthenogenetic, Received in revised form Darevskia rostombekowi. The present study aims to identify morphological features of these two species 22 June 2020 and the potential gene introgression between them in the area of sympatry. External morphological Accepted 30 June 2020 features provided the evidence of specific morphology in D. raddei and D. portschinskii: the species Available online 14 July 2020 differed in scalation and ventral coloration pattern, however, they had some proportional similarities Corresponding Editor: Alexander Kupfer within both sexes of the two species. Males of both species had relatively larger heads and shorter bodies than females. Males of D. raddei were slightly larger than males of D. -

Institutionalization of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in The

Institutionalization of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in the Georgian Regions (ICCAMGR) Analysis of the Capacities of the Local Authorities: Environmental and Climate Change Management April 22, 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. ANALYSIS OF THE CAPACITIES OF LOCAL AUTHORITIES 2 This Analysis of the Capacities of the Local Authorities: Environmental and Climate Change Management was developed by the Institutionalization of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in Georgian Regions (ICCAMGR) program implemented by the National Association of the Local Authorities of Georgia (NALAG). It falls under Agreement Number AID-114-A-12-00001. This report was made possible through the support of the American people through USAID/Caucasus. Its contents are the sole responsibility of National Association of the Local Authorities of Georgia (NALAG) and ACT and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Prepared for: USAID/Caucasus American Embassy 11 George Balanchine Street Tbilisi 0131 Georgia Tel: + 995 (32) 254 4147 www.usaid.gov ANALYSIS OF THE CAPACITIES OF LOCAL AUTHORITIES 3 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the United States Agency for International Development’s Georgia Mission (USAID/Caucasus) for this project. In addition, the authors would like to thank the ICCAMGR’s partners and governmental counterparts, the Ministry of Energy and the Ministry of Environment and Resource Protection, -

River Systems and Their Water and Sediment Fluxes Towards the Marine Regions of the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea Earth System: an Overview

Review Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.19514 River systems and their water and sediment fluxes towards the marine regions of the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea earth system: An overview Serafeim E. POULOS Laboratory of Physical Geography, Section of Geography & Climatology, Department of Geology & Geoenvironment, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis-Zografou, 10584, Attiki Corresponding author: [email protected] Handling Editor: Argyro ZENETOS Received: 22 January 2019; Accepted: 6 July 2019; Published on line: 5 September 2019 Abstract A quantitative assessment of the riverine freshwater, suspended and dissolved sediment loads is provided for the watersheds of the four primary (Western Mediterranean-WMED, Central Mediterranean-CMED, Eastern Mediterranean-EMED and Black Sea- BLS) and eleven secondary marine regions of the Mediterranean and Black Sea Earth System (MBES). On the basis of measured values that cover spatially >65% and >84% of MED and BLS watersheds, respectively, water discharge of the MBES reaches annually almost the 1 million km3, with Mediterranean Sea (including the Marmara Sea) providing 576 km3 and the Black Sea (included the Azov Sea) 418 km3. Among the watersheds of MED primary marine regions, the total water load is distributed as follows: WMED= 180 km3; CMED= 209 km3; and EMED= 187 km3. The MBES could potentially provide annually some 894 106 t of suspended sediment load (SSL), prior to river damming, most of which (i.e., 708 106 t is attributed to MED). -

Ethnobiology of Georgia

SHOTA TUSTAVELI ZAAL KIKVIDZE NATIONAL SCIENCE FUNDATION ILIA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS ETHNOBIOLOGY OF GEORGIA ISBN 978-9941-18-350-8 Tbilisi 2020 Ethnobiology of Georgia 2020 Zaal Kikvidze Preface My full-time dedication to ethnobiology started in 2012, since when it has never failed to fascinate me. Ethnobiology is a relatively young science with many blank areas still in its landscape, which is, perhaps, good motivation to write a synthetic text aimed at bridging the existing gaps. At this stage, however, an exhaustive representation of materials relevant to the ethnobiology of Georgia would be an insurmountable task for one author. My goal, rather, is to provide students and researchers with an introduction to my country’s ethnobiology. This book, therefore, is about the key traditions that have developed over a long history of interactions between humans and nature in Georgia, as documented by modern ethnobiologists. Acknowledgements: I am grateful to my colleagues – Rainer Bussmann, Narel Paniagua Zambrana, David Kikodze and Shalva Sikharulidze for the exciting and fruitful discussions about ethnobiology, and their encouragement for pushing forth this project. Rainer Bussmann read the early draft of this text and I am grateful for his valuable comments. Special thanks are due to Jana Ekhvaia, for her crucial contribution as project coordinator and I greatly appreciate the constant support from the staff and administration of Ilia State University. Finally, I am indebted to my fairy wordmother, Kate Hughes whose help was indispensable at the later stages of preparation of this manuscript. 2 Table of contents Preface.......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. A brief introduction to ethnobiology...................................................................................... -

Abhazya/Gürcistan: Tarih – Siyaset – Kültür

TÜR L Ü K – CEMAL GAMAKHARİA LİA AKHALADZE T ASE Y Sİ – H ARİ T : AN T S Cİ R A/GÜ Y ABHAZ ZE D İA AKHALA İA L İA İA R ABHAZYA/GÜRCİSTAN: ,6%1 978-9941-461-51-4 L GAMAKHA L TARİH – SİYASET – KÜLTÜR CEMA 9 7 8 9 9 4 1 4 6 1 5 1 4 CEMAL GAMAKHARİ A Lİ A AKHALADZE ABHAZYA/GÜRCİ STAN: TARİ H – Sİ YASET – KÜLTÜR Tiflis - İ stanbul 2016 UDC (uak) 94+32+008)(479.224) G-16 Yayın Kurulu: Teimuraz Mjavia (Editör), Prof. Dr. Roin Kavrelişvili, Prof. Dr. Erdoğan Altınkaynak, Prof. Dr. Rozeta Gujejiani, Giorgi Iremadze. Gürcüce’den Türkçe’ye Prof. Dr. Roin Kavrelişvili tarafından tercüme edil- miştir. Bu kitapta Gürcistan’ın Özerk Cumhuriyeti Abhazya’nın etno-politik tarihi üzerine dikkat çekilmiş ve bu bölgede bulunan kadim Hıristiyan kül- türüne ait ana esaslar ile ilgili genel görüşler ortaya konulmuştur. Etnik, siyasi ve kültürel açıdan bakıldığında, Abhazya’nın günümüzde sahip olduğu toprakların, tarihin eski dönemlerinden bu yana Gürcü bölgesi olduğu ve bölgede gerçekleşen demografik değişiklilerin ancak Orta Çağın son dönemlerinde gerçekleştiği anlaşılmaktadır. Bu kitabın yazarları 1992 – 1993 yılları arasında Rusya tarafından Gürcistan’a karşı girişilen hibrid savaşlardan ve 2008’de gerçekleştirilen açık saldırganlıktan bahsetmektedirler. Burada, savaştan sonra meydana gelen insani felaketler betimlenmiş, Abhazya’nın işgali ile Avrupa- Atlantik sahasına karşı yapılan hukuksuz jeopolitik gelişmeler anlatılmış ve uluslararası kuruluşların katılımıyla Abhazya’da sürekli ortaya çıkan çatışmaların barışçıl bir yol ile çözülmesinin gerekliliği üzerinde durulmuştur. Düzenleme Levan Titmeria ISBN 978-9941-461-51-4 İçindekiler Giriş (Prof. Dr. Cemal Gamakharia) ..................................... 5 1. -

European Red List of Birds

European Red List of Birds Compiled by BirdLife International Published by the European Commission. opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission or BirdLife International concerning the legal status of any country, Citation: Publications of the European Communities. Design and layout by: Imre Sebestyén jr. / UNITgraphics.com Printed by: Pannónia Nyomda Picture credits on cover page: Fratercula arctica to continue into the future. © Ondrej Pelánek All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). Photographs should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without written permission from the copyright holder. Available from: to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed Published by the European Commission. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. ISBN: 978-92-79-47450-7 DOI: 10.2779/975810 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Printed in Hungary. European Red List of Birds Consortium iii Table of contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................1 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................5 1. -

Abkhazia: Deepening Dependence

ABKHAZIA: DEEPENING DEPENDENCE Europe Report N°202 – 26 February 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. RECOGNITION’S TANGIBLE EFFECTS ................................................................... 2 A. RUSSIA’S POST-2008 WAR MILITARY BUILD-UP IN ABKHAZIA ...................................................3 B. ECONOMIC ASPECTS ....................................................................................................................5 1. Dependence on Russian financial aid and investment .................................................................5 2. Tourism potential.........................................................................................................................6 3. The 2014 Sochi Olympics............................................................................................................7 III. LIFE IN ABKHAZIA........................................................................................................ 8 A. POPULATION AND CITIZENS .........................................................................................................8 B. THE 2009 PRESIDENTIAL POLL ..................................................................................................10 C. EXTERNAL RELATIONS ..............................................................................................................11 -

Glaciers Change Over the Last Century, Caucasus Mountains, Georgia

1 Glaciers change over the last century, Caucasus Mountains, 2 Georgia, observed by the old topographical maps, Landsat 3 and ASTER satellite imagery 4 5 L. G. Tielidze 6 7 Department of Geomorphology, Vakhushti Bagrationi Institute of Geography, Ivane 8 Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, 6 Tamarashvili st. Tbilisi 0177, Georgia 9 10 Correspondence to: L. G. Tielidze ([email protected]) 11 12 13 Abstract 14 15 The study of glaciers in the Caucasus began in the first quarter of the 18th century. The 16 first data on glaciers can be found in the works of great Georgian scientist Vakhushti 17 Bagrationi. After almost hundred years the foreign scientists began to describe the 18 glaciers of Georgia. Information about the glaciers of Georgia can be found in the 19 works of W. Abich, D. Freshfield, G. Radde, N. Dinik, I. Rashevskiy, A. Reinhardt etc. The 20 first statistical information about the glaciers of Georgia are found in the catalog of the 21 Caucasus glaciers compiled by K. Podozerskiy in 1911. Then, in 1960s the large-scale 22 (1 : 25 000, 1 : 50 000) topographic maps were published, which were compiled in 23 1955–1960 on the basis of the airphotos. On the basis of the mentioned maps R. 24 Gobejishvili gave quite detailed statistical information about the glaciers of Georgia. Then 25 in 1975 the results of glaciers inventory of the former USSR was published, where the 26 statistical information about the glaciers of Georgia was obtained on the basis of the 27 almost same time (1955-1957) aerial images. -

DG Consulting

REF. NO.: IDA/TGSP/CS/CQS/02-2016 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION OF LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR CONSTRUCTION OF 500 KV JVARI-TSKALTUBO OVERHEAD TRANSMISSION LINE AND ASSOCIATED SUBSTATION ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT INTERIM REPORT TECHNICAL PART, BASELINE AND VISUAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT CLIENT: JSC GEORGIAN STATE ELECTROSYSTEM PROJECT : TRANSMISSION GRID STRENGTHENING PROJECT (TGSP) – P147348 41380_INTERIM_ V11, TBILISI, AUGUST 2017 DG Consulting Ltd Address: 10, Mirza Gelovani Street, 0160, Tbilisi, Georgia; Registered in Georgia, No 205 280 998; Tel: +995 322 380 313; +995 599 500 778; [email protected] 41380_r01_v02_GSE_ESIA_JvariTskaltubo Page 2 of 196 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 8 ESIA Report Preparation Process and Structure ..................................................................... 9 2. Legal and Regulatory Framework .................................................................................................. 12 Georgian laws applicable for the environmental impact assessment .................................. 12 The technical standards and guidelines ........................................................................ 19 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment in Georgia .................................................... 20 Current EIA legislation ..................................................................................................