Literacy on Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Archived Documents: Issue 2017 2018 Second Edition"

2017-2018 CURRICULUM CATALOG SECOND EDITION Haywood Community College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) to award associate degrees, diplomas, and certificates. The Board of Trustees of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) is responsible for making the final determination on reaffirmation of accreditation based on the findings contained in this committee report, the institution’s response to issues contained in the report, other assessments relevant to the review, and application of the Commission’s policies and procedures. Final interpretation of the Principles of Accreditation and final action on the accreditation status of the institution rest with SACSCOC Board of Trustees. Haywood Community College issues this catalog to furnish prospective students and other interested persons with information about the school and its programs. Announcements contained herein are subject to change without notice and may not be regarded as binding obligations to the College or to the State of North Carolina. Curriculum offerings are subject to sufficient enrollment, with not all courses listed in this catalog being offered each term. Course listings may be altered to meet the needs of the individual program of study or Instruction Division. Upon enrolling at Haywood Community College, students are required to abide by the rules, regulations, and student code of conduct as stated in the most current version of the catalog/handbook, either hardcopy or online. For academic purposes, students must meet program requirements of the catalog of the first semester of attendance, given continued enrollment (fall and spring). If a student drops out a semester (fall or spring), the student follows the catalog requirements for the program of study in the catalog for the year of re-enrollment. -

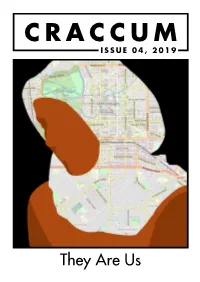

Issue 04 2019

CRACCUM ISSUE 04, 2019 They Are Us 360 International Fair Wednesday 3 April 2019 10am to 2pm OGGB Business School, Level 0 Come along to our 360 International Fair and learn about the overseas opportunities the University has to offer. Learn about: • Semester and year-long exchange Take • Winter and summer schools • Global internship programmes yourself • Partners and providers • Scholarships/funding options global. Michaella, Tainui Semester in the UK auckland.ac.nz/360 [email protected] 04 EDITORIAL 06 NEWS SUMMARY contents 08 NEWS LONGFORM 10 CHRISTCHURCH 16 THINGS DO WHEN FACEBOOK AND INSTAGRAM ARE DOWN 20 ROBINSON 24 REVIEWS 26 SPOTLIGHT 32 LIFESTYLE 32 TINDER HORROR STORIES 34 FOOD REVIEW 36 QUIZ WANT TO CONTRIBUTE? 37 HOROSCOPES Send your ideas to: 38 THE PEOPLE TO BLAME. News [email protected] Features [email protected] Arts [email protected] Community and Lifestyle [email protected] Illustration [email protected] Need feedback on what you’re working on? [email protected] Hot tips on stories [email protected] Your 1 0 0 % s t u d e n t o w n e d u b i q . c o . n z bookstore on campus! 03 editorial. Jokes Aside, Be Kind to One Another BY BAILLEY VERRY Each week Craccum’s esteemed Editor-in-Chief writes their editorial 10 minutes before deadline and this is the product of that. When putting together Craccum, we are one week be- solidarity that the country has already shown is heart- hind the news cycle between the time we go to print and warming. -

A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University The aT ylor Magazine Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections Spring 1996 Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996)" (1996). The Taylor Magazine. 91. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines/91 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aT ylor Magazine by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keeping up with technology on the World Wide Web • The continuing influence ofSamuel Morris • Honor Roll ofDonors - 1995 A MAGAZINE FOR TAYLOR UNIVERSITY ALUMNI AND FRIENDS 1846*1996 SPRING 1996 PRECIS his issue of tlie Taylor Magazine is devoted to the first 50 years of Taylor's existence. Interestingly, I have just finished T reading The Year of Decision - 1846 by Bernard DeVoto. The coincidence is in some ways intentional because a Taylor schoolmate of mine from the 1950's, Dale Murphy, half jokingly recommended that I read the book as I was going to be making so many speeches during our sesquicentennial celebration. As a kind of hobby, I have over the years taken special notice of events concurrent with the college's founding in 1846. The opera Carman was first performed that year and in Germany a man named Bayer discovered the value of the world's most universal drug, aspirin. -

{TEXTBOOK} a Long Days Evening Pdf Free Download

A LONG DAYS EVENING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bilge Karasu | 168 pages | 29 Nov 2012 | City Lights Books | 9780872865914 | English | Monroe, OR, United States A Long Days Evening PDF Book Otherwise, you could end up with evidence of your crying session all over your face, long after the last tear has dried. The holiday was first recognized in the United States as the result of an executive order signed by President Lyndon B. Inevitably, however, the day comes when we all get brave enough to venture toward that mysterious appliance that promises to turn frozen foods into edible treats. For some people, hearing "I love you" will do it. As we all know, however, they must be handled with care in order to avoid certain pitfalls. Here is a prime example of why women tend to live longer than men. Start by enjoying these hilarious photos featuring people who are definitely having a worse day than you are. For others, it was a failed attempt at mimicry. This is funny because Novak had actually been on that show. It sucks to realize that someone has stolen your jewelry, electronics and other valuables, but the sense of violation that comes with being burgled is even worse. Going to bed at the same time is a reliable way to ensure you have time for each other. Because of this, they had to hire actors who could think on their feet. This can cement you as a strong couple and show everyone that you're each other's priority. Unfortunately, the song the cast really wanted got snapped up by another show. -

Using Workflows to Automate the Boring Parts of Sales

USING WORKFLOWS TO AUTOMATE THE BORING PARTS O F S A L E S KYLE JEPSON EMILY MORGAN #INBOUND19 Kyle Emily Jepson Morgan Workflow Wrangler Automation Alchemist On average, salespeople only spend about 35% of their time 35% selling. Source: InsideSales.com 27% 35% 27% of salespeople are spending an hour or more on 27% data entry each day. Source: HubSpot Research SALES REP TASK TIME ALLOCATION 14.8% 14% 11.6% 11.1%10.1% 8.7% 7% 6.3% 5.6% 5.3% 4.5% 3.9% SOURCE: InsideSales.com BUILD SEQUENCES to automate your emails and tasks. BUILD SEQUENCES to automate your emails and tasks. USE WORKFLOWS FOR A FASTER, EASIER, MORE ACCURATE, AND REPORTABLE SALES PROCESS USE WORKFLOWS FOR A FASTER, EASIER, MORE ACCURATE, AND REPORTABLE SALES PROCESS LIFECYCLE STAGES MARKETING SALES QUALIFIED LEAD QUALIFIED LEAD LEAD OPPORTUNITY CUSTOMER QUALIFIED BY QUALIFIED BY A DEAL IS OPENED A DEAL IS A SYSTEM HUMAN CLOSED/WON SITTING IN A PARK BORINGOMETER SITTING IN WAITING AT THE A PARK DMV BORINGOMETER RESOURCES PAGE CONSULTING.HUBSPOT.COM/INBOUND UPDATING PROPERTIES BORINGOMETER UPDATING PROPERTIES BORINGOMETER TERRITORY ASSIGNMENT ENROLLMENT → SET CONTACT/COMPANY PROPERTY Sales Territory → Zone A ACTION UPDATING STAGE/STATUS BORINGOMETER UPDATING STAGE/STATUS BORINGOMETER LIFECYCLE STAGES MARKETING SALES QUALIFIED LEAD QUALIFIED LEAD LEAD OPPORTUNITY CUSTOMER QUALIFIED BY QUALIFIED BY A DEAL IS OPENED A DEAL IS A SYSTEM HUMAN CLOSED/WON LEADS GENERATED LEADS SENT FROM TO SALES MARKETING LEAD HANDOFF MARKETING LEAD QUALIFIED LEAD QUALIFIED BY A SYSTEM SALES-READY ACTIONS Form Submission: Request Consultation OR Form Submission: Request Quote OR Page View: Contains “/pricing” SALES-READY ACTIONS Form Submission: Request Consultation OR Form Submission: Request Quote OR Page View: Contains “/pricing” OR Contact Property: HubSpot Score > 135 Update the Contact Property: Lifecycle Stage ↓ MARKETING QUALIFIED LEAD Update the Contact Property: Lead Status ↓ NEW Familiarizing your client with HubSpot andSuppression defining a plan to work Lists towards to their particularInclude: goals. -

Ringo Starr “Mr

Trolleywood MOTION IN PICTURES Ringo Starr “Mr. Conductor’s” peculiar legacy Behind the Scenes of The Second-Worst The Dirty Truth about Magical Mystery Tour Show of All Time? Road Trip Movies Pg. 14 Pg. 34 Pg. 42 December 2016 Contents Ringo Starr: Busy Beyond the Beatles “Mr. Conductor’s” peculiar legacy Advertisement 26 Photo Credits for Cover Image: FinnSpotVlogs on YouTube Behind the Scenes The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour 14 The Dirty Truth about Road Trip Movies More Than a Gimmick 34 Trucky Throwback Mother of All Failures 42 3 Contents Letter from the Editor 9 Travel Destination Rusty’s TV & Movie Car Museum 10 International Films The Cyclist 17 Vehicle Roundup Wheel & Heel Advertisement 20 Hating Your Legacy Thomas’s Bittersweet Creator 22 The George Carlin Who I Knew Remembering a Different Side of Carlin 32 Propmaster Furious 7’s Wrecked Cars 37 Rewind Review From 1968: Yellow Submarine 44 Anthropomorphic Profile The Magic School Bus 46 4 5 Masthead Editor-in-Chief Contributing Editors Jerrika L. Waller David Bianculli, Rosalind Cummings- Senior Editors Yeates, Dan Schneider, Nicholas Jones, Jane Warren, Britt Allcroft, Bryan Andrew O’Donnell, Amanda O’Keefe Alexander, Renata Adler, Jim Halpert, Art Director Pam Beesly, Dwight Schrute, Andy Logan Jerv Waller, Jr. Bernard, Michael Scott, Stanley Hudson, Phyllis Vance, Kelly Erin Hannon, Toby Web Editor Flenderson, Ryan Howard, Angela Nina Arsenault Martin, Kelly Kapoor, Meredith Palmer, Advertisement Associate Editors Kevin Malone, Darryl Philbin, Oscar Michael Fiedler, Gino -

Open Final Kennedy SHC 2018.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE COLLEGE OF INFORMATION SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY DATA FUSION OF SECURITY LOGS TO MEASURE CRITICAL SECURITY CONTROLS TO INCREASE SITUATION AWARENESS MATTHEW KENNEDY SPRING 2018 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Security and Risk Analysis with honors in Security and Risk Analysis Reviewed and approved* by the following: Nicklaus A. Giacobe Assistant Teaching Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Director, Undergraduate Programs Thesis Advisor Dinghao Wu Associate Professor Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ii ABSTRACT In Jan. 2018, a NIST draft to the Cybersecurity Framework called for the development of cybersecurity metrics, saying such work would be a “major advancement and contribution to the cybersecurity community (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2017b).” Unfortunately, organizations and researchers continue to make little progress at measuring security. Along with this, research around measuring security fails to present detailed guides on how to implement security metrics collection and reporting in an organization. This research seeks to explore how measuring the CIS (formally SANS) Critical Security Controls, through data fusion of security logs, has the potential to increase situation awareness to strategic decision makers, and systems administrators. Metrics are built for each of the sub controls for Critical Security Control 8: Malware Defenses. Along with the development of these metrics, a proof of concept is implemented in a computer network designed to mimic a small business that is using Symantec Endpoint Protection and Splunk. A Splunk dashboard is created to monitor, in real time, the status of Critical Security Control 8.1 and 8.2. -

The Invisible Journalist: Understanding the Role of the Documentary Filmmaker As Portrayed in the Office

The Invisible Journalist: Understanding the Role of the Documentary Filmmaker as Portrayed in The Office Massiel Bobadilla JOUR575 –Joe Saltzman Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture May 5, 2011 Bobadilla 2 ABSTRACT: This study aims to shed light on the enigmatic ‘mockumentary’ filmmaker of The Office by using specific examples from the show’s first six seasons to understand how the filmmaker is impacted by and impacts concepts of journalism and the invasion of privacy. Similarly, the filmmaker in the American version of The Office will not only be compared and contrasted to the role of the filmmaker in the British version, but also will be compared to the anthropologic ethnographer an “outsider” attempting to capture life as faithfully as possible in a community to which he/she does not belong. The American interpretation of The Office branched out of Ricky Gervais’s British original of the same name with the pilot episode hitting the airwaves on NBC on March 24, 2005,1 to largely mixed reviews from critics, but a strong showing among viewers.2 The show’s basic premise is that of a faux documentary providing an inside look at the day-to-day life of the employees of a mid-level paper company. The primary focus centers on the socially inept branch manager, his even more inept right-hand-man, and the budding romance of the young and earnest paper salesman and the mild-mannered receptionist who happens to be inconveniently engaged to one of the branch’s warehouse workers. What was the Slough branch of Wernham Hogg in the U.K. -

Cacti Hug Notebook : Puppies & Rainbows by Baxter the Dog Books

CACTI HUG NOTEBOOK : PUPPIES & RAINBOWS BY BAXTER THE DOG BOOKS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jennifer Hart | 46 pages | 14 Nov 2018 | Baxter The Dog Books | 9781732158825 | English | none Cacti Hug Notebook : Puppies & Rainbows by Baxter The Dog Books PDF Book Deer Spiral Notebook By Tasmiya. They are the manager of the Elmore Shopping , only in Anais's imagination. We said hi, got out of the van and all shook her hand. We were taking essential supplies and guns in holsters if things got really tricky. Castle as the end goal here. I opened my eyes. Cheryl and I were left alone. Baxter The Dog is no stranger to fantastic creatures. Anyway, a little while back I was due for a meeting at the record company and I was uncharacteristically late. She is one of Sarah's original characters brought to life by the magic notebook. A giant Girls Aloud pancake, muah ha ha ha ha ha! Tags: fairies, fairy, tinkerbell, glitter, sparkle, sparkles, sparkly, glimmer, glittery, inspirational, motivational, quotes, quote, quoting, typography, disney, disneyland, disney girl, girls, teen, youth, young, tween, teen girl, girlie, pretty, princess, tink, tinker bell, peter pan, shine, stars, cute, kids, disney fan, fan, disney love, bokeh. We were bundled into a minibus and Huey drove us to a non-descript suburb somewhere on the outskirts of London. Do you understand? She gets to sing some nights and gets paid in pork scratchings. Different versions of the butterfly can be seen in " The Kiss ," and " The Wicked. The study of mental health disorders and the genetics behind these disorders can be greatly enhanced by the use of induced pluripotent stem cells iPSC. -

Transport, Technology and Ideology in the Work of Will Self

Durham E-Theses Transport, Technology and Ideology in the Work of Will Self GLEGHORN, JAMES,MARTIN How to cite: GLEGHORN, JAMES,MARTIN (2017) Transport, Technology and Ideology in the Work of Will Self, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12135/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Transport, Technology and Ideology in the Work of Will Self James Martin Gleghorn Thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Studies Durham University 2017 Contents List of Abbreviations …………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Statement of Copyright ……………………………………………….………………………………….. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Chapter 1: Ironic Entrapment and Fundamental Instability: Will Self’s Literary Aesthetic …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 42 Chapter 2: The Book of Dave …………………………………………………………………………… 85 Chapter 3: Driving Fiction ……………………………………………………………………………….122 Chapter 4: Walking to Hollywood …………………………………………………………………. 164 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 198 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 208 1 List of Abbreviations D – Dorian DM – Dr. -

Spinsters, Old Maids, and Cat Ladies: a Case Study in Containment Strategies

SPINSTERS, OLD MAIDS, AND CAT LADIES: A CASE STUDY IN CONTAINMENT STRATEGIES Katherine Sullivan Barak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2014 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Vikki Krane Graduate Faculty Representative Sarah Smith Rainey Marilyn Motz © 2014 Katherine Sullivan Barak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor Using Michel Foucault’s notion of “containment strategies,” this dissertation argues that representations of the crazy cat lady, the reprehensible animal hoarder, the proud spinster, and the unproductive old maid negatively frame independent, single women as models of failed White womanhood. These characters must be contained because they intrinsically transgress social norms, query gender roles, and challenge the limitations of mediated womanhood. In order to explore the role of representation, this dissertation provides a suggestive history of the ways spinsters and old maids evolved into their current iteration, the cat lady. The research begins by tracing cultural representations of cats and women from 2000 BCE through the early modern period. After this retrospective, the research focuses on two particular points of cultural anxiety connected to changing gender roles: the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries. During the former, the media characterized spinsters and old maids as selfish, proud, unnatural, unproductive, and childish in newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets. Rather than focusing exclusively on the negative coverage, this dissertation deeply analyzes three transgressive novels, Agnes Grey, An Old-Fashioned Girl, and Lolly Willowes: Or the Loving Huntsman, to contextualize the ways positive representations of spinsters and old maids could threaten patriarchal society. -

Crazy Chicken Lady : Composition Notebook: Wide Ruled Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CRAZY CHICKEN LADY : COMPOSITION NOTEBOOK: WIDE RULED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Greenyx Publishing | 202 pages | 23 Oct 2019 | Independently Published | 9781701906945 | English | none Crazy Chicken Lady : Composition Notebook: Wide Ruled PDF Book Tags: nature, butterflies, biology, seamless, detailed, australian, humming bird, birds, insects, ladybug, plants, flowers, native, retro, vintage, moth, eggs, egg, scarab, caterpillar, banksia, pretty, floral, flower, australia, botanical, flora, fauna, entomology, vintage, flora and fauna, butterflies and birds, natural wonder, collage, biology pattern, repeating pattern, summer colors, summer colours, winter white, ferns, roses, pomegranate. That's what she said funny quote Spiral Notebook By rehabtiger. Tags: newfoundland dog, newfie, easter, bunny, easter basket, easter eggs easter chicks. Removed from Favorites. Tags: ron, swanson, parks, rec, recreation, waffle, egg, eggs, bacon, breakfast, food, quote, tv, leslie, knope, parks and rec. Tags: rooster art, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster tablet cases, rooster, rooster, rooster, rooster sleeves, rooster, rooster, rooster phone wallets. Tags: portugal flag, flag of portugal, portuguese flag, rooster blood, rooster, blood, portuguese rooster, portugal rooster, portuguese, portugal, galo, galo de barcelos, barcelos, barcelos portugal, lisbon, lisboa, portuguesa, rooster art, good luck rooster, good luck, madeira, funchal, azorres, new bedford, ludlow, massachusettes, mijumi, mijumi art, rooster of portugal, portuguese feast, lady of fatima, feast of the blessed sacrament, portuguese flag rooster. Tags: chickie, blues, egg, arrival, cracked. Tags: eat sleep horse racing repeat, eat sleep, horse racing, repeat, horse, horse rider, horse riding, farm, farmer, farming, animal, farm animal, funny, humor, saying. Previous Next Showing 1 - of 28, unique designs. Tags: acrylic rooster, fun rooster painting, rooster, crowing rooster, loose rooster painting, red and white rooster.