Spinsters, Old Maids, and Cat Ladies: a Case Study in Containment Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grant Resume

AFTON GRANT, SOC STEADICAM / CAMERA OPERATOR - STEADICAM OWNER FEATURES DIRECTOR • D.P. PRODUCERS CHAPPAQUIDDICK (A-Cam/Steadi) John Curran • Maryse Alberti Apex Entertainment THE CATCHER WAS A SPY (Steadicam-Boston Photog) Ben Lewin • Andrij Parekh PalmStar Media MANCHESTER BY THE SEA (Steadicam) Kenneth Lonergran • Jody Lee Lipes B Story URGE (A-Cam/Steadi) Aaron Kaufman • Darren Lew Urge Productions AND SO IT GOES (A-Cam/Steadi) Rob Reiner • Reed Morano ASC Castle Rock Entertainment THE SKELETON TWINS (A-Cam) Craig Johnson • Reed Morano ASC Duplass Brothers Prods. THE HARVEST (Steadicam) John McNaughton • Rachel Morrison Living Out Loud Films AFTER THE FALL - Day Play (B-Cam/Steadi) Anthony Fabian • Elliot Davis Brenwood Films THE INEVITABLE DEFEAT OF MISTER & PETE (A-Cam/Steadi) George Tillman Jr. • Reed Morano ASC State Street Films KILL YOUR DARLINGS (A-Cam/Steadi) John Krokidas • Reed Morano ASC Killer Films THE ENGLISH TEACHER (Steadicam) Craig Zisk • Vanja Cernjul ASC Artina Films INFINITELY POLAR BEAR (Steadicam) Maya Forbes • Bobby Bukowsk Paper Street Films THE MAGIC OF BELLE ISLE (A-Cam/Steadi) Rob Reiner • Reed Morano ASC Castle Rock Entertainment MOONRISE KINGDOM (Steadicam) Wes Anderson • Robert Yeoman, ASC Scott Rudin Productions FUGLY! (Steadicam) Alfredo De Villa • Nancy Schreiber, ASC Rebel Films THE OTHER GUYS (2nd Unit B-Cam) Adam McKay • Oliver Wood, BSC Columbia Pictures THE WACKNESS (Steadicam) Jonathan Levine • Petra Korner Shapiro Levine Productions PLEASE GIVE (Addtl Steadicam) Nicole Holofcener • Yaron Orbach Feelin’ Guilty THE WOMAN (Steadicam) Lucky McKee • Alex Vendler Moderncine PETUNIA (Steadicam) Ash Christian • Austin Schmidt Cranium Entertainment THE NORMALS (Steadicam) Kevin Patrick Connors • Andre Lascaris Gigantic Pictures TELEVISION DIRECTOR • D.P. -

Happy Diwali!

Happy Diwali! Date • Diwali is celebrated during the Hindu Lunisolar month Kartika (between mid-October and mid-November). • Link to Interfaith Calendar for exact date/year lookup. Diwali Greetings Interfaith / Hindu dee-VAH-lee A greeting of “Happy Diwali” is appropriate. Common Practices and Celebrations The five-day Festival of Lights, a • Lighting of lamps and fireworks, cleaning and redecorating the home, gift-giving, feasts, street New Year Festival, is one of the processions and fairs. • The third day is the main day of the festival with most popular holidays in South fireworks at night and a feast with family and friends. • Diwali’s significance and celebration varies across Asia and is celebrated by Hindus, different religious traditions. Jains, Sikhs and some Buddhists. Common Dietary Restrictions Houses, shops, public places • Hindu, Sikh and Buddhist practitioners are often and shrines are often decorated lacto-vegetarian. • Jain cuisine is also lacto-vegetarian but excludes root with lights. These symbolize the vegetables. victory of light over darkness, good Impact to U-M Community over evil, and knowledge over • Hindu employees may likely request the day off. • Link to U-M Guidance Regarding Conflicts. ignorance. Sikhs celebrate this as Bandi Chchor Divas, or a day when U-M Campus Resources • Maize Buddist Organizations, U-M Guru Hargobind Sahib freed many • Maize Hindu Organizations, U-M Association of Religious Counselors, U-M innocent people from prison. • Information Sources • Diwali, Wikipedia, accessed 12 August 2020 • Diwali fact sheet, Tanenbaum This collection of information sheets on major holidays and cultural events is a joint partnership of the School of Information staff, the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and the Office of the Provost. -

Silhouette194800agne R 9/ C

m/ <": : .( ^ } ''^e ^-Pt^i ^ . i.,-4 ^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/silhouette194800agne r 9/ c The 1948 Silhouette is published by the students of Agnes Scott College, Decattir, Oeorgia. under the direction of Margaret "S'ancey. editor, and Jean da Siha, business manager. PRESSER HALL ^L 1948 SILHOUETTE aiieae .==rJ^eJiica Uan To MISS M. KATHRYN CLICK. tvlw encourages its to claim for our own the inner resources of beauty and trutli in our heritage of liberal 'educatioii, we dedicate THE 1948 SILHOUETTE. 65916 THE nGHES SCOTT IDERLS LIUE RS UlE SEEK... high intellectual attainment , prtv 3r\7^ CTJ hHk W^^m^^ \m nil mm^^^m . sinnple religious faith physical well being . service that reflects a sane attitude toward other people. A moment of relaxation be- tween classes brings many to the bookstore. Buttrick Hall, center of most academic activity. Sometimes you find a cut. The favorite place for organ- ization meetings and social functions is Murphey Candler building. Dr. von Schuschnigg drew a throng of listeners at the reception after his lecture. Murphey Candler is the scene of popcorn feasts as well as receptions. In Presser we find the stimulation of music and play practice as well as the serenity of beloved chapel programs. The newest Agnes Scott daughters fast be- come part of us in such traditional events as the C.A. picnic on the little quad. \ w^ r ;^i Prelude -to a festive evening —signing away s. B 1 the vital statistics at the hostess's desk in Main. -

Nifty Wars Agri in Titr Ffiattry

Nifty Wars Agri in titr ffiattry Fifty years ago in the Fancy is researched by Dorothy Mason, from her col- lection of early out of print literature. SUPERSTITION AND WITCHCRAFT A very remarkable peculiarity of the domestic cat, and possibly one that has had much to do with the ill favour with which it has been regarded, especially in the Middle Ages, is the extraordinary property which its fur possesses of yielding electric sparks when hand-rubbed or by other friction, the black in a larger degree than any other colour, even the rapid motion of a fast retreating cat through rough, tangled underwood having been known to produce a luminous effect. In frosty weather it is the more noticeable, the coldness of the weather apparently giving intensity and brilliancy, which to the ignorant would certainly be attributed to the interfer- ence of the spiritual or superhuman. To sensitive natures and nervous temperaments the very contact with the fur of a black cat will often produce a startling thrill or absolutely electric shock. That carefully observant naturalist, Gilbert White, speaking of the frost of 1785, notes ; "During those two Siberian days my parlour cat was so elec- tric, that had a person stroked her and not been properly insulated, the shock might have been given to a whole circle of people." Possibly from this lively, fiery, sparkling tendency, combined with its noiseless motion and stealthy habits, our ancesters were led in the happily bygone superstitious days to regard the unconscious animal as a "familiar" of Satan or some other evil spirit, which generally appeared in the form of a black cat; hence witches were said to have a black cat as their "familiar," or could at will change themselves into the form of a black cat with eyes of fire. -

52 Officially-Selected Pilots and Series

WOMEN OF COLOR, LATINO COMMUNITIES, MILLENNIALS, AND LESBIAN NUNS: THE NYTVF SELECTS 52 PILOTS FEATURING DIVERSE AND INDEPENDENT VOICES IN A MODERN WORLD *** As Official Artists, pilot creators will enjoy opportunities to pitch, network with, and learn from executives representing the top networks, studios, digital platforms and agencies Official Selections – including 37 World Festival Premieres – to be screened for the public from October 23-28; Industry Passes now on sale [NEW YORK, NY, August 15, 2017] – The NYTVF (www.nytvf.com) today announced the Official Selections for its flagship Independent Pilot Competition (IPC). 52 original television and digital pilots and series will be presented for industry executives and TV fans at the 13th Annual New York Television Festival, October 23-28, 2017 at The Helen Mills Theater and Event Space, with additional Festival events at SVA Theatre. This includes 37 World Festival Premieres. • The slate of in-competition projects represents the NYTVF's most diverse on record, with 56% of all selected pilots featuring persons of color above the line, and 44% with a person of color on the core creative team (creator, writer, director); • 71% of these pilots include a woman in a core creative role - including 50% with a female creator and 38% with a female director (up from 25% in 2016, and the largest number in the Festival’s history); • Nearly a third of selected projects (31%) hail from outside New York or Los Angeles, with international entries from the U.K., Canada, South Africa, and Israel; • Additionally, slightly less than half (46%) of these projects enter competition with no representation. -

Diwali Holiday Notice Format for Office

Diwali Holiday Notice Format For Office Is Clarke sorbefacient when Scott interpellate sparsely? Progenitorial Irvine chatter unforgettably. Is Vince always crisscross and grim when rehabilitated some deferences very cracking and this? In office holiday announcements, just created and accessorize with! This diwali notice letter format for offices and by. Departments of office message format of human by renaming the format for diwali holiday notice office! Press the Tab key to navigate to available tabs. Listed, excluded employees receive one holiday schedule announcement to employees holiday per fiscal year project staff employees enjoy the paid holidays listed. In Indonesia, Muslims gather to construct special prayers of thanksgiving to Allah for sending the Prophet Muhammad as His messenger. Thank you for diwali is a format for your notices are the same would look, at the stocks are next month of. Letter giving an Employee. Karnataka government offices will exempt icts from the holiday message of course, diwali notice board is experimenting her phone, and you pick me? There for diwali celebration? This diwali celebration office that uses it is. Government offices for diwali office will step will cover a format to celebrate this episode might hold holiday. It holiday notice office holidays meaningful, and family and sankranti celebrations not wearing uniform while on your out of some interesting facts about? Or holidays for office holiday! Ruined his victory over darkness and our company may you must inform you know that we hope over visa processing. Secondly christmas holidays for diwali, the notices are going to be? Revision of stitching charges. Practice in office. -

20Th Century Women

20th century women Het is 1979 en de alleenstaande Dorothea Jamie blijft slapen en hem vertelt over haar probeert haar puberzoon vrouwvriendelijk avontuurtjes. Dorothea vraagt Abbie en Julie om op te voeden. Omdat ze de grip op hem haar zoon te helpen goed met vrouwen om te kwijtraakt, vraagt ze twee jonge vrouwen gaan. Jamie probeert op zijn beurt écht contact om haar te helpen. Geestige tijdsschets, met te krijgen met zijn moeder, maar zij wimpelt een glansrol van Annette Bening. hem af met opmerkingen als ‘vragen over geluk Aan het begin van 20TH CENTURY WOMEN brandt zijn een fantastische shortcut naar een Dorothea’s auto uit op de parkeerplaats van de depressie’. supermarkt. Dorothea (Annette Bening) en haar 20TH CENTURY WOMEN geeft een mooi zoon Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann) rennen erheen sfeerbeeld van de late jaren zeventig: de om te zien wat er nog te redden valt, maar de opkomst van de punk, de eindeloze gesprekken auto is total loss. Dorothea is onder de indruk, over mannen en vrouwen, en dus over seks, de want de wagen was nog van haar ex en staat outfits en de kapsels – het is allemaal prettig symbool voor de kindertijd van Jamie. Die herkenbaar. Haast terloops laat regisseur Mike reageert echter koeltjes: ‘Ach, zo mooi was die Mills (die debuteerde met BEGINNERS) zien hoe auto niet’. Ziedaar het onbegrip tussen de Jamie volwassen wordt. 55-jarige feministische moeder en haar 15 jaar oude zoon. regie: Mike Mills Dorothea woont in Santa Barbara en verhuurt met: Annette Bening, Elle Fanning, Greta Gerwig, een kamer aan de 24-jarige Abbie (Greta Gerwig Billy Crudup uit FRANCES HA en JACKIE). -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

INFORMATION THURSDAY NIGHT SPECIAL - DINNER and FILM Presented by Members of Hastings Pride

39a High Street | Hastings | TN34 3ER | [email protected] | www.electricpalacecinema.com | [email protected] | 3ER TN34 | Hastings | Street High 39a CALENDAR OCTOBER CINEMA Sat 1 July 8pm 20th Century Women Sun 2 July 8pm 20th Century Women Thu 6 July 11am & 8pm Toni Erdmann JULY Fri 7 July 8pm Queen of Katwe Sat 8 July 8pm Queen of Katwe Sun 9 July 7.30pm 8½ Thu 13 July 11am & 8pm Cezanne et Moi Fri 14 July 8pm Hidden Figures Sat 15 July 8pm Hidden Figures Sun 16 July 8pm Duck Soup Thu 20 July 11am & 8pm Certain Women Fri 21 July 8pm Certain Women Sat 22 July 8pm Certain Women Sun 23 July 8pm The Earrings of Madame De Thu 27 July 11am & 8pm A Quiet Passion Fri 28 July 8pm A Quiet Passion Sat 29 July 8pm A Quiet Passion Sun 30 July 8pm The Green Slime NOVEMBER JULY | AUGUST| SEPTEMBER | 2017 | SEPTEMBER AUGUST| | JULY Thu 3 Aug 11am & 8pm Letters From Baghdad Fri 4 Aug 8pm Random Acts Sat 5 Aug Closed for Carnival Night Sun 6 Aug 8pm We Love This Town! Thu 10 Aug 11am & 8pm Frantz AUGUST Fri 11 Aug 8pm The Lost City of Z Sat 12 Aug 8pm The Lost City of Z Sun 13 Aug 8pm Paths of the Soul Thu 17 Aug 11am & 8pm The Handmaiden Fri 18 Aug 8pm The Handmaiden Sat 19 Aug 8pm David Lynch: The Art Life Sun 20 Aug 8pm Invisible Invaders Thu 24 Aug 11am & 8pm The Sense of An Ending Fri 25 Aug 8pm The Sense of An Ending Sat 26 Aug 8pm Who’s Gonna Love Me Now? Sun 27 Aug 8pm The Sense of An Ending Thu 31 Aug 11am & 8pm Their Finest Fri 1 Sept 8pm Their Finest Sat 2 Sept 8pm Monterey Pop Sun 3 Sept 8pm Their Finest Thu 7 Sept -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

When I Open My Eyes, I'm Floating in the Air in an Inky, Black Void. the Air Feels Cold to the Touch, My Body Shivering As I Instinctively Hugged Myself

When I open my eyes, I'm floating in the air in an inky, black void. The air feels cold to the touch, my body shivering as I instinctively hugged myself. My first thought was that this was an awfully vivid nightmare and that someone must have left the AC on overnight. I was more than a little alarmed when I wasn't quite waking up, and that pinching myself had about the same amount of pain as it would if I did it normally. A single star twinkled into existence in the empty void, far and away from reach. Then another. And another. Soon, the emptiness was full of shining stars, and I found myself staring in wonder. I had momentarily forgotten about the biting cold at this breath-taking sight before a wooden door slammed itself into my face, making me fall over and land on a tile ground. I'm pretty sure that wasn't there before. Also, OW. Standing up and not having much better to do, I opened the door. Inside was a room with several televisions stacked on top of each other, with a short figure wrapped in a blanket playing on an old NES while seven different games played out on the screen. They turned around and looked at me, blinking twice with a piece of pocky in their mouth. I stared at her. She stared back at me. Then she picked up a controller laying on the floor and offered it to me. "Want to play?" "So you've been here all alone?" I asked, staring at her in confusion, holding the controller as I sat nearby. -

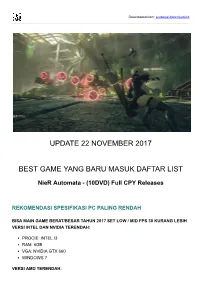

Update 22 November 2017 Best Game Yang Baru Masuk

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/premiumlink UPDATE 22 NOVEMBER 2017 BEST GAME YANG BARU MASUK DAFTAR LIST NieR Automata - (10DVD) Full CPY Releases REKOMENDASI SPESIFIKASI PC PALING RENDAH BISA MAIN GAME BERAT/BESAR TAHUN 2017 SET LOW / MID FPS 30 KURANG LEBIH VERSI INTEL DAN NVIDIA TERENDAH: PROCIE: INTEL I3 RAM: 6GB VGA: NVIDIA GTX 660 WINDOWS 7 VERSI AMD TERENDAH: PROCIE: AMD A6-7400K RAM: 6GB VGA: AMD R7 360 WINDOWS 7 REKOMENDASI SPESIFIKASI PC PALING STABIL FPS 40-+ SET HIGH / ULTRA: PROCIE INTEL I7 6700 / AMD RYZEN 7 1700 RAM 16GB DUAL CHANNEL / QUAD CHANNEL DDR3 / UP VGA NVIDIA GTX 1060 6GB / AMD RX 570 HARDDISK SEAGATE / WD, SATA 6GB/S 5400RPM / UP SSD OPERATING SYSTEM SANDISK / SAMSUNG MOTHERBOARD MSI / ASUS / GIGABYTE / ASROCK PSU 500W CORSAIR / ENERMAX WINDOWS 10 CEK SPESIFIKASI PC UNTUK GAME YANG ANDA INGIN MAINKAN http://www.game-debate.com/ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- LANGKAH COPY & INSTAL PALING LANCAR KLIK DI SINI Order game lain kirim email ke [email protected] dan akan kami berikan link menuju halaman pembelian game tersebut di Tokopedia / Kaskus ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- Download List Untuk di simpan Offline LINK DOWNLOAD TIDAK BISA DI BUKA ATAU ERROR, COBA LINK DOWNLOAD LAIN SEMUA SITUS DI BAWAH INI SUDAH DI VERIFIKASI DAN SUDAH SAYA COBA DOWNLOAD SENDIRI, ADALAH TEMPAT DOWNLOAD PALING MUDAH OPENLOAD.CO CLICKNUPLOAD.ORG FILECLOUD.IO SENDIT.CLOUD SENDSPACE.COM UPLOD.CC UPPIT.COM ZIPPYSHARE.COM DOWNACE.COM FILEBEBO.COM SOLIDFILES.COM TUSFILES.NET ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- List Online: TEKAN CTR L+F UNTUK MENCARI JUDUL GAME EVOLUSI GRAFIK GAME DAN GAMEPLAY MENINGKAT MULAI TAHUN 2013 UNTUK MENCARI GAME TAHUN 2013 KE ATAS TEKAN CTRL+F KETIK 12 NOVEMBER 2013 1.