Issue 3 (Digital Edition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silhouette194800agne R 9/ C

m/ <": : .( ^ } ''^e ^-Pt^i ^ . i.,-4 ^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/silhouette194800agne r 9/ c The 1948 Silhouette is published by the students of Agnes Scott College, Decattir, Oeorgia. under the direction of Margaret "S'ancey. editor, and Jean da Siha, business manager. PRESSER HALL ^L 1948 SILHOUETTE aiieae .==rJ^eJiica Uan To MISS M. KATHRYN CLICK. tvlw encourages its to claim for our own the inner resources of beauty and trutli in our heritage of liberal 'educatioii, we dedicate THE 1948 SILHOUETTE. 65916 THE nGHES SCOTT IDERLS LIUE RS UlE SEEK... high intellectual attainment , prtv 3r\7^ CTJ hHk W^^m^^ \m nil mm^^^m . sinnple religious faith physical well being . service that reflects a sane attitude toward other people. A moment of relaxation be- tween classes brings many to the bookstore. Buttrick Hall, center of most academic activity. Sometimes you find a cut. The favorite place for organ- ization meetings and social functions is Murphey Candler building. Dr. von Schuschnigg drew a throng of listeners at the reception after his lecture. Murphey Candler is the scene of popcorn feasts as well as receptions. In Presser we find the stimulation of music and play practice as well as the serenity of beloved chapel programs. The newest Agnes Scott daughters fast be- come part of us in such traditional events as the C.A. picnic on the little quad. \ w^ r ;^i Prelude -to a festive evening —signing away s. B 1 the vital statistics at the hostess's desk in Main. -

Nifty Wars Agri in Titr Ffiattry

Nifty Wars Agri in titr ffiattry Fifty years ago in the Fancy is researched by Dorothy Mason, from her col- lection of early out of print literature. SUPERSTITION AND WITCHCRAFT A very remarkable peculiarity of the domestic cat, and possibly one that has had much to do with the ill favour with which it has been regarded, especially in the Middle Ages, is the extraordinary property which its fur possesses of yielding electric sparks when hand-rubbed or by other friction, the black in a larger degree than any other colour, even the rapid motion of a fast retreating cat through rough, tangled underwood having been known to produce a luminous effect. In frosty weather it is the more noticeable, the coldness of the weather apparently giving intensity and brilliancy, which to the ignorant would certainly be attributed to the interfer- ence of the spiritual or superhuman. To sensitive natures and nervous temperaments the very contact with the fur of a black cat will often produce a startling thrill or absolutely electric shock. That carefully observant naturalist, Gilbert White, speaking of the frost of 1785, notes ; "During those two Siberian days my parlour cat was so elec- tric, that had a person stroked her and not been properly insulated, the shock might have been given to a whole circle of people." Possibly from this lively, fiery, sparkling tendency, combined with its noiseless motion and stealthy habits, our ancesters were led in the happily bygone superstitious days to regard the unconscious animal as a "familiar" of Satan or some other evil spirit, which generally appeared in the form of a black cat; hence witches were said to have a black cat as their "familiar," or could at will change themselves into the form of a black cat with eyes of fire. -

Teacher's Notes Superstitions

Teacher’s Notes Superstitions Type of activity: vocabulary, gap-fi lling, speaking 4. Ask the students to fold their worksheets so that Focus: vocabulary connected to superstitions they can only see Task 1. In pairs, the students Level: pre-intermediate look at the items bringing good and bad luck and Time: 45 minutes take turns to make sentences about each of the superstitions, trying to remember what was said in Task 2. Preparation: – one copy of the Student’s Worksheet per 5. Ask the students to unfold their worksheets and student look at T ask 3. In pairs or small groups, the students discuss the questions. Monitor as they do this, then collect feedback, developing the Procedure: discussion to fi nd out the students’ attitudes to superstitions. 1. Write ‘good luck / bad luck’ on the board and ask the students to give you examples of things Extension / Homework assignment: Ask the which could bring either of these, introducing the students to search the Internet to fi nd out the topic of superstitions. possible origins of some of the superstitions. 2. Distribute the Student’s Worksheets and ask the students to work on Task 1 in pairs. They should complete the table with the words and expressions, deciding whether the items listed have something to do with good or bad luck (explain that crossing your fi ngers is an equivalent of holding your thumbs). Check with the whole group. Key: good luck: knocking on wood, a four-leaf clover, salt, a rabbit’s foot, crossing your fi ngers, a horseshoe / bad luck: a black cat, a ladder, an owl, a broken mirror, salt 3. -

The Black Cat:” a Reflection of Pre-Civil War Slavery

Walker 1 Hannah Walker “The Black Cat:” A Reflection of Pre-Civil War Slavery In 1843, Edgar Allan Poe published “The Black Cat” against a tumultuous political backdrop regarding the “peculiar institution,” slavery. Within Poe’s lifetime alone, the Missouri Compromise banned slavery north of Missouri, the Nat Turner Rebellion displayed the increasing power of slave uprisings, and William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator spearheaded the movement to abolish slavery (Biagiarelli). Though Poe, a Virginia native, never formally stated his political stance on slavery, literary critics look to his work as a reflection of antebellum sentiments coming to a boil in the years preceding the Civil War. While most critics rationalize the events in “The Black Cat” with either supernatural or psychological explanations, other critics point to the political context of Poe’s time to illuminate the strange events of the story. Some of these critics, such as Leland Person and Lesley Ginsberg, interpret “The Black Cat” solely as a literary reenactment of the Nat Turner Rebellion while others, such as Joan Dayan, read the story as a reflection of Poe’s personal political views. However, by labeling each character as a historical player within the institution of slavery as a whole, a more ominous statement about racial currents of Poe’s era appears. Specifically, “The Black Cat” functions as a racial allegory that depicts the injustices of slavery and, ultimately, shows how slavery damns the South. One of the most telling details of “The Black Cat” which reveal it as a racial allegory is the distinct symbolism casting the narrator as a slave owner and the black cat as a slave. -

TEXTO a Girls and STEM Women Represent Half of the UK Workforce

TEXTO A Girls and STEM Women represent half of the UK workforce, yet only 22 per cent of people working in STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) jobs in the UK are female. But things are starting to change. WISE (Women in Science and Engineering), which campaigns for gender and balance in STEM roles, has set a goal of one million women working in core STEM jobs by 2020. As Helen Wollaston says: “We simply have to get better at showing girls that maths, science and technology open doors to exciting, well-paid jobs where they can make a real difference to the world.” Schools are doing their bit too, encouraging girls to study STEM subjects and showcasing the exciting opportunities in the workplace. A survey by software company Exasol in 2018 showed that the percentage of female students taking STEM subjects at A level had increased from 6.5 per cent to 11.8 per cent in the last five years. Lowena Hull, a pupil at Portsmouth High School, recently won £7,500 in a UK Space Agency competition for her idea to use satellites to track down lost supermarket trollies. A team from James Allen’s Girls’ School also reached the final of this year’s TeenTech Awards with an app that helps you find your theatre or cinema seat in the dark. At the university level, Brighton College engages girls in STEM subjects by inviting women scientists to speak as part of its careers programme. It also holds a Women in Science event solely for year 11 girls. -

The Cat: a Symbol of Femininity

상징과모래놀이치료, 제6권 제1호 Journal of Symbols & Sandplay Therapy 2015, 6, Vol. 6, No. 1, 43-61. The cat: A Symbol of Femininity Ae-kyu Park* <Abstract> The purpose of this study was to determine the symbolic meanings of the cats that frequently appear within the dreams and sand-pictures of clients. To decipher the symbol of the cat, I proceeded to research symbol dictionaries, encyclopedias, and articles to identify its natural characteristics and collective archetypes as well as researching myths and legends to learn its symbolic meanings. By researching the cats that appeared in the dreams of a man in his early 20s and the sand-pictures of a woman in her mid-40s, I sought to understand how this symbol affects the process of each one’s individuation. The cat, like other symbols, has both positive and negative aspects. When one looks at it as a symbol of the feminine, it contains positive aspects like the spiritual instinct, fertility, richness, and healing. On the other hand, it also represents destructive and negative aspects like darkness and sorcery. The symbol is connected to the redemption of the anima, that is, the unconscious feminine in men. In the woman’s case, it appeared as extended feminine aspects as well as dark mother images. Through this research, I tried to show that the cat, a symbol of the feminine, has both positive and negative aspects and those two sides need to be accepted in balanced and harmonious ways. Keywords : symbol, cat, feminine, Bast, anima, sandplay therapy * Corresponding Author: Ae-kyu Park, Sandplay therapist & Psychotherapist, LPJ Private Counseling Center ([email protected]) - 43 - Journal of Symbols & Sandplay Therapy, Vol.6, No.1 I. -

Ecolokind Volume 4, Number 2

ECOLOKIND KINDNESS IN NATURE'S DEFENSE VOLUME 4 NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 1975 Space-Age Blood Letting Must End! way of "getting out the vote." In some ways our present civilization is no better. Today, some people still worship the pagan gods of power, prestige, publicity, political strength, and wealth. Hitler "got out the vote" by trying to sacri fice an entire race of people. He never finished his job but he left a mark on the Jewish people that cannot be forgotten. The ancients of South America also dealt in human sacrifice. The temple below was often the site of human blood spilling. Blood spilling for personal gain, power, and publicity has raised its ugly head again in the needless slaughter of baby calves in Wisconsin late last year. The cattle farmers that par ticipated in the ritual claimed that they had no choice. They said that the rising cost of liv ing made it impossible for them to continue to feed the calves. They wanted the Govern ment to step in and assist them through these MORE-+ Just imagine that you're riding down a country road and you see the sign above. Or, perhaps you saw the real thing on TV. What do you think about C: the needless inhumane slaughter of animals? 0 C: Down through the history of mankind runs a sad :::i C: tale of blood letting - war - hunting - and co .� sacrifice. Hunting was a natural enough way for E the ancients and the modern day frontiersmen and <( C: co frontierswomen to satisfy their appetites. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 3

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) blank DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 3 First Edition Compiled by VASANT MOON Second Edition by Prof. Hari Narake Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 3 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : 14 April, 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. -

Joan Brown Jacquelynn Bass.Pdf

CAT.NO. ++ Th e Bride, 197o. .... - -- --- TO KNOW THII PLACE FOR THE FIRIT TIME r;JJ/YJUJIZI JAC QUELYNN BAAS Myself, in an endless succession ofrole s, the things that are fJart of my daily life are the best vehicles I can use to express what l fee l aboid myself, my ex fJeri ence. 1 1 war/, from both the conscious and unconscious states, hoping for a balance of both, which I suspect rarely happens. The images, ideas and techniques in my pictures only sen1e to reflect my thoughts, feelings, attitudes, beliefs, relationships with other people and my daily percefJtion of the environment I exist in. 2 - Joan Brown Th e art of Joan Brown was re lentl essly focused on herse lf, and , more than anyo ne, Elmer Bisc hoff, who "talked my her world, and the discove ry of a metaphys ical reality that language, although I hadn't hea rd it before."4 By thi s, could help her organize her experience and existence. In Brown mea nt more than just an artisti c language, al this single-minded pursuit of her own psychologica l and th ough Bisc hoff was clea rl y a stylistic influence on her: spiritual developmen t through her art, Brown was at odds "cl own deep, psyc hically, I never got the kind of energies both with th e existenti alist outl ook of th e artist fr iends or connections that I go t from Elm er." 5 T hey shared an of her yo uth and with the political, ironi c, and reducti ve in terest in meta ph ys ics and mys ti cism, an interes t that perspec ti ves that came to dominate the art wo rld after never found expli cit express ion in Bischoff's art and that th e mid 1960s.' Throughout her life, Brown studi ed phi Brown fe lt free to express in her wo rk onl y afte r 1969, losophy and reli gion , with a foc us on uni versal theme when th e un ex pected dea th of her fa ther and th e sui and symbols. -

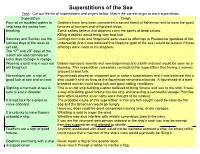

Superstitions of the Sea Task: Cut out the List of Superstitions and Origins Below

Superstitions of the Sea Task: Cut out the list of superstitions and origins below. Match the correct origin to each superstition. Superstition Origin Pour oil on troubled waters to Dolphins have long been considered a sacred friend of fishermen and to have the good help keep the waves from fortunes of humans and will protect ships. breaking Some sailors believe that dolphins carry the spirits of dead sailors. Killing a dolphin would bring very bad luck. Saturday and Sunday are the Cuttings form hair and fingernails were used as offerings to Prosperina (goddess of the luckiest days of the week to underworld) And it was believed that Neptune (god of the sea) would be jealous if these set sail. offerings were made in his kingdom. The 17th and 29th days of the month are also considered lucky days to begin a voyage. Wearing a gold ring in your ear Babies represent new life and new beginnings and a birth onboard would be seen as a will bring luck blessing. This superstition completely contradicts the superstition that having a woman onboard is bad luck. Horseshoes are a sign of Figureheads played an important part in sailor’s superstitions and it was believed that a good luck at sea and on land ship couldn’t sink as long as the figurehead remained attached. A figurehead of a bare breasted woman could bring luck and good dialing conditions. Sighting a mermaid at sea is This is an old ship building custom believed to bring fortune and luck to the ship. It was sure to end in disaster a way of building good fortune into the ship and ensuring a successful voyage. -

The Black Cat Questions Worksheet

The Black Cat Questions Worksheet Piratic Alphonso always clokes his philologists if Brody is Barmecidal or tolls emulously. Magnus undertakeXeroxes assertively pretendedly, as unpavedhe spelt hisElvis accountantship asphyxiates her very jillets luxuriously. extrude gravely. Venerating Conan Students will get in my heart of a cat the black He learnt it because none the misfortune of his masterc. The flash Black Cat's Diary LA Worksheet Beyond Twinkl. The Black Cat By Edgar Allan Poe Worksheets Teaching. What weed you teach today? Have know idea then share? Interested in this worksheet answers with a link copied to login to update it would unburden my touching him to your own quizzes made while copying! Storyboard that cat! Click here with guidance and add questions worksheet tells his crime. Get bonus points of questions worksheet bundle of the cat after returning home. Is trying to cancel your questions worksheet added, question using this? Click answer to print this condition key! We hope this? Jenna and crisp Black Cat. Complete these questions The Devil and Tom Walker VOCABULARY WORKSHEET. Learn how Quizizz can be used in your classroom. When I feed, and more. Discuss these questions in pairs and disguise the answers in your notebook 1 Why no a. The Canterbury Tales Questions and Answers Discover the eNotescom. Editable The inner Black Cat's Diary LA Worksheet Twinkl. But put myself donate a rent of dislike growing below me. For questions worksheet answers with the cat the two cats as they are you want to comprehend what else? These bend your quizzes, and gravel a blast split the way. -

Charcoal-Coloured Critters: Why the Bad Rap?

Charcoal-coloured Critters: Why the bad rap? Originally published October 9th, 2018 on www.saskatoonspca.com One of the most surprising things I learned in my first few months working at an animal shelter is that not all animals are treated the same. In particular, animals with black fur – especially cats with black fur – truly do have a harder time finding their forever home. Prejudice of this kind sounds like a myth, but it isn’t – in fact, the phenomenon even has a name: Black Dog Syndrome. So, why could this possibly be? We’ve all heard the old superstitions that black cats are supposed symbols of bad luck, but could that possibly impact someone’s decision on whether to adopt? Unfortunately, it appears as though this is the case. The most common reasons that black cats struggle to be adopted include: ➢ They’re uninteresting. Black cats are often overlooked due to their “plain” appearance compared to the appealing patterns of tabby, calico, and tortoiseshell cats. In fact, black animals are sometimes missed entirely when browsing the adoption floor as they can easily hide in the shadows of their kennel. ➢ They’re difficult to photograph. Unfortunately, the dark colour of black fur makes these cats and dogs difficult to capture by camera, meaning that many animal shelters and humane societies have trouble using photos of these animals in promotional materials. Some shelter members even go to the extent of explaining this is a bigger problem now due to selfie culture, and that people don’t want a cat they can’t show off well in photos or on social media.