Climate Change, the Ruined Island, and British Metamodernism By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panels Seeking Participants

Panels Seeking Participants • All paper proposals must be submitted via the Submittable (if you do not have an account, you will need to create one before submitting) website by December 15, 2018 at 11:59pm EST. Please DO NOT submit a paper directly to the panel organizer; however, prospective panelists are welcome to correspond with the organizer(s) about the panel and their abstract. • Only one paper proposal submission is allowed per person; participants can present only once during the conference (pre-conference workshops and chairing/organizing a panel are not counted as presenting). • All panel descriptions and direct links to their submission forms are listed below, and posted in Submittable. Links to each of the panels seeking panelists are also listed on the Panel Call for Papers page at https://www.asle.org/conference/biennial-conference/panel-calls-for-papers/ • There are separate forms in Submittable for each panel seeking participants, listed in alphabetical order, as well as an open individual paper submission form. • In cases in which the online submission requirement poses a significant difficulty, please contact us at [email protected]. • Proposals for a Traditional Panel (4 presenters) should be papers of approximately 15 minutes-max each, with an approximately 300 word abstract, unless a different length is requested in the specific panel call, in the form of an uploadable .pdf, .docx, or .doc file. Please include your name and contact information in this file. • Proposals for a Roundtable (5-6 presenters) should be papers of approximately 10 minute-max each, with an approximately 300 word abstract, unless a different length is requested in the specific panel call, in the form of an uploadable .pdf, .docx, or .doc file. -

Climate Fiction

CLIMATE FICTION Instructor: Christopher A. Walker Course Number: EN/ES 337 Lecture: MW 2:30-3:45 in Miller 319 Office Hours: Mondays 4:00-6:00 (and by appointment) in Miller 216 Mailbox: Miller 216 Email: [email protected] Course Description Contemporary fiction is now investigating the possibilities and limits of story-telling in the era of global climate change. These works, referred to as “climate fiction” or “cli-fi,” explore humanity’s connection to- and impact upon Earth by asking questions such as: what will human and nonhuman communities look like after sea-level rise, desertification, and biodiversity loss remap our planet?; how might species evolve in response to ecological collapse?; what affects— melancholy, despair, hope—will eulogize a lost home-world? Reading cli-fi novels, short stories, poetry, and film, this course will situate our texts within the Environmental Humanities, an interdisciplinary field that combines scientific and cultural discourses about the environment with humanistic concerns for social justice. Working through the narrative conventions of the utopian, dystopian, and apocalyptic genres, we will ask how cli- fi not only narrates impending disaster on a global scale but also strives to imagine a more just future, one that combines environmentalism and social equality. These texts will be paired with excerpts from philosophical and ecocritical writings which will aid our development of the humanistic methodologies needed to analyze and appreciate this new genre. Course Materials Items with an asterisk (*) on reserve in Miller Library. Books to purchase: (Available at The Colby Bookstore) Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake (ISBN 978-0-385-72167-7) (2003) * J. -

The Butterfly Phenomena: a Study of Climate Change on Barbara Kingsolver’S Flight Behaviour

© 2018 JETIR October 2018, Volume 5, Issue 10 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) The Butterfly phenomena: A Study of Climate Change on Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour. Rejani G.S Research Scholar (Ph.D) (Reg.No.18113154012020) S.T Hindu College ,Nagercoil Affiliated to Manonmanium Sundaranar University, Abhishekapatti.Tirunelveli. Abstract Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour is a clarion call for the forestalled eco-apocalypse, climate change or global warming .Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Maggie Gees The Ice People, Jeanette Winterson’s The Stone Gods and many other novels in the same vein are futuristic. Even though there is always imagination in fiction, Flight Behaviour does not focus on the aftermath of any global disaster. Rather it reflects the actuality of climate change and Monarch butterfly migration. It also focuses on the story of a young woman trying to change her life, and a deeply humane account of working people responding to the local effects of the global climate crisis. Kingsolver has carved a career from examining social issues in her novels, from economic inequality to environmentalism. Flight Behaviour portrays the inducement and consequences of climate change that forms the butterfly effect. The paper throws light on the enormous consequence of climate change and the ignorance of reality. Keywords - Climate change, Butterfly phenomenon , Futuristic, Global Warming and Environmentalism. Climate change is the defining challenge of our age. The science is clear, climate change is happening, the impact is real. The time to act is now. -Ban Ki-Moon Climate novel is an emerging literary genre that has caught much attention and popularity in recent years. -

Alexis Wright's Carpentaria and the Swan Book

Exchanges: The Interdisciplinary Research Journal Climate Fiction and the Crisis of Imagination: Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria and The Swan Book Chiara Xausa Department of Interpreting and Translation, University of Bologna, Italy Correspondence: [email protected] Peer review: This article has been subject to a Abstract double-blind peer review process This article analyses the representation of environmental crisis and climate crisis in Carpentaria (2006) and The Swan Book (2013) by Indigenous Australian writer Alexis Wright. Building upon the groundbreaking work of environmental humanities scholars such as Heise (2008), Clark (2015), Copyright notice: This Trexler (2015) and Ghosh (2016), who have emphasised the main article is issued under the challenges faced by authors of climate fiction, it considers the novels as an terms of the Creative Commons Attribution entry point to address the climate-related crisis of culture – while License, which permits acknowledging the problematic aspects of reading Indigenous texts as use and redistribution of antidotes to the 'great derangement’ – and the danger of a singular the work provided that the original author and Anthropocene narrative that silences the ‘unevenly universal’ (Nixon, 2011) source are credited. responsibilities and vulnerabilities to environmental harm. Exploring You must give themes such as environmental racism, ecological imperialism, and the slow appropriate credit violence of climate change, it suggests that Alexis Wright’s novels are of (author attribution), utmost importance for global conversations about the Anthropocene and provide a link to the license, and indicate if its literary representations, as they bring the unevenness of environmental changes were made. You and climate crisis to visibility. -

"Archived Documents: Issue 2017 2018 Second Edition"

2017-2018 CURRICULUM CATALOG SECOND EDITION Haywood Community College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) to award associate degrees, diplomas, and certificates. The Board of Trustees of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) is responsible for making the final determination on reaffirmation of accreditation based on the findings contained in this committee report, the institution’s response to issues contained in the report, other assessments relevant to the review, and application of the Commission’s policies and procedures. Final interpretation of the Principles of Accreditation and final action on the accreditation status of the institution rest with SACSCOC Board of Trustees. Haywood Community College issues this catalog to furnish prospective students and other interested persons with information about the school and its programs. Announcements contained herein are subject to change without notice and may not be regarded as binding obligations to the College or to the State of North Carolina. Curriculum offerings are subject to sufficient enrollment, with not all courses listed in this catalog being offered each term. Course listings may be altered to meet the needs of the individual program of study or Instruction Division. Upon enrolling at Haywood Community College, students are required to abide by the rules, regulations, and student code of conduct as stated in the most current version of the catalog/handbook, either hardcopy or online. For academic purposes, students must meet program requirements of the catalog of the first semester of attendance, given continued enrollment (fall and spring). If a student drops out a semester (fall or spring), the student follows the catalog requirements for the program of study in the catalog for the year of re-enrollment. -

Issue 04 2019

CRACCUM ISSUE 04, 2019 They Are Us 360 International Fair Wednesday 3 April 2019 10am to 2pm OGGB Business School, Level 0 Come along to our 360 International Fair and learn about the overseas opportunities the University has to offer. Learn about: • Semester and year-long exchange Take • Winter and summer schools • Global internship programmes yourself • Partners and providers • Scholarships/funding options global. Michaella, Tainui Semester in the UK auckland.ac.nz/360 [email protected] 04 EDITORIAL 06 NEWS SUMMARY contents 08 NEWS LONGFORM 10 CHRISTCHURCH 16 THINGS DO WHEN FACEBOOK AND INSTAGRAM ARE DOWN 20 ROBINSON 24 REVIEWS 26 SPOTLIGHT 32 LIFESTYLE 32 TINDER HORROR STORIES 34 FOOD REVIEW 36 QUIZ WANT TO CONTRIBUTE? 37 HOROSCOPES Send your ideas to: 38 THE PEOPLE TO BLAME. News [email protected] Features [email protected] Arts [email protected] Community and Lifestyle [email protected] Illustration [email protected] Need feedback on what you’re working on? [email protected] Hot tips on stories [email protected] Your 1 0 0 % s t u d e n t o w n e d u b i q . c o . n z bookstore on campus! 03 editorial. Jokes Aside, Be Kind to One Another BY BAILLEY VERRY Each week Craccum’s esteemed Editor-in-Chief writes their editorial 10 minutes before deadline and this is the product of that. When putting together Craccum, we are one week be- solidarity that the country has already shown is heart- hind the news cycle between the time we go to print and warming. -

Anthropocene Monsters in Jeff Vandermeer's the Southern Reach

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies March 2017: 71-96 DOI: 10.6240/concentric.lit.2017.43.1.05 Brave New Weird: Anthropocene Monsters in Jeff VanderMeer’s The Southern Reach Gry Ulstein Faculty of Humanities Utrecht University, The Netherlands Abstract This paper investigates and compares language and imagery used by contemporary ecocritics in order to argue that the Anthropocene discourse contains significant parallels to cosmic horror discourse and (new) weird literature. While monsters from the traditional, Lovecraftian weird lend themselves well to Anthropocene allegory due to the coinciding fear affect in both discourses, the new weird genre experiments with ways to move beyond cosmic fear, thereby reimagining the human position in the context of the Anthropocene. Jeff VanderMeer’s trilogy The Southern Reach (2014) presents an alien system of assimilation and ecological mutation into which the characters are launched. It does this in a manner that brings into question human hierarchical coexistence with nonhumans while also exposing the ineffectiveness of current existential norms. This paper argues that new weird stories such as VanderMeer’s are able to rework and dispel the fearful paralysis of cosmic horror found in Lovecraft’s literature and of Anthropocene monsters in ecocritical debate. The Southern Reach and the new weird welcome the monstrous as kin rather than enemy. Keywords Anthropocene, climate change, ecology, climate fiction, horror, weird, Jeff VanderMeer 72 Concentric 43.1 March 2017 The Thing cannot be described—there is no language for such abysms of shrieking and immemorial lunacy, such eldritch contradictions of all matter, force, and cosmic order. The Thing of the idols, the green, sticky spawn of the stars, had awaked to claim his own. -

Climates of Mutation: Posthuman Orientations in Twenty-First Century

Climates of Mutation: Posthuman Orientations in Twenty-First Century Ecological Science Fiction Clare Elisabeth Wall A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in English York University Toronto, Ontario January 2021 © Clare Elisabeth Wall, 2021 ii Abstract Climates of Mutation contributes to the growing body of works focused on climate fiction by exploring the entangled aspects of biopolitics, posthumanism, and eco-assemblage in twenty- first-century science fiction. By tracing out each of those themes, I examine how my contemporary focal texts present a posthuman politics that offers to orient the reader away from a position of anthropocentric privilege and nature-culture divisions towards an ecologically situated understanding of the environment as an assemblage. The thematic chapters of my thesis perform an analysis of Peter Watts’s Rifters Trilogy, Larissa Lai’s Salt Fish Girl, Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl, and Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam Trilogy. Doing so, it investigates how the assemblage relations between people, genetic technologies, and the environment are intersecting in these posthuman works and what new ways of being in the world they challenge readers to imagine. This approach also seeks to highlight how these works reflect a genre response to the increasing anxieties around biogenetics and climate change through a critical posthuman approach that alienates readers from traditional anthropocentric narrative meanings, thus creating a space for an embedded form of ecological and technoscientific awareness. My project makes a case for the benefits of approaching climate fiction through a posthuman perspective to facilitate an environmentally situated understanding. -

Climate Change in Literature and Culture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank CLIMATE CHANGE IN LITERATURE AND CULTURE: CONVERSION, SPECULATION, EDUCATION by STEPHEN SIPERSTEIN A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Stephen Siperstein Title: Climate Change in Literature and Culture: Conversion, Speculation, Education This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Professor Stephanie LeMenager Chairperson Professor David Vazquez Core Member Professor William Rossi Core Member Professor Kari Norgaard Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2016 ii © 2016 Stephen Siperstein iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Stephen Siperstein Doctor of Philosophy Department of English June 2016 Title: Climate Change in Literature and Culture: Conversion, Speculation, Education This dissertation examines an emergent archive of contemporary literary and cultural texts that engage with the wicked problem of anthropogenic climate change. Following cultural geographer Michael Hulme, this project works from the assumption that climate change is as much a constellation of ideas as it is a set of material realities. I draw from a diverse media landscape so as to better understand how writers, artists, and activists in the global north are exploring these ideas and particularly what it means to be human in a time of climate change. -

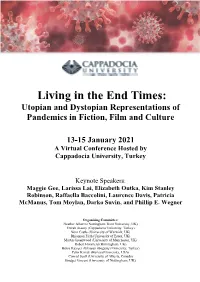

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

Variations of Human Transformation in Science Fiction

Beyond Human Boundaries: Variations of Human Transformation in Science Fiction Sayyed Ali Mirenayat Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Ida Baizura Bahar Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Rosli Talif Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Manimangai Mani Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Abstract—Science Fiction is a literary genre of technological changes in human and his life; and is full of imaginative and futuristic concepts and ideas. One of the most significant aspects of Science Fiction is human transformation. This paper will present, firstly, an overview on the history of Science Fiction and some of the most significant sci-fi stories, and will also explore the elements of human transformation in them. Later, it will explain the term of transhumanism as a movement which follows several transformation goals to reach immortality and superiority of human through advanced technology. Next, the views by a number of prominent transhumanists will be outlined and discussed. Finally, three main steps of transhumanism, namely transhuman, posthuman, and cyborg, will be described in details through notable scholars’ views in which transhuman will be defined as a transcended version of human, posthuman as a less or non-biological being, and cyborg as a machine human. In total, this is a conceptual paper on an emerging trend in literary theory development which aims to engage critically in an overview of the transformative process of human by technology in Science Fiction beyond its current status. Index Terms—science fiction, transformation, transhumanism, transhuman, posthuman, cyborg I. -

A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University The aT ylor Magazine Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections Spring 1996 Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996)" (1996). The Taylor Magazine. 91. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines/91 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aT ylor Magazine by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keeping up with technology on the World Wide Web • The continuing influence ofSamuel Morris • Honor Roll ofDonors - 1995 A MAGAZINE FOR TAYLOR UNIVERSITY ALUMNI AND FRIENDS 1846*1996 SPRING 1996 PRECIS his issue of tlie Taylor Magazine is devoted to the first 50 years of Taylor's existence. Interestingly, I have just finished T reading The Year of Decision - 1846 by Bernard DeVoto. The coincidence is in some ways intentional because a Taylor schoolmate of mine from the 1950's, Dale Murphy, half jokingly recommended that I read the book as I was going to be making so many speeches during our sesquicentennial celebration. As a kind of hobby, I have over the years taken special notice of events concurrent with the college's founding in 1846. The opera Carman was first performed that year and in Germany a man named Bayer discovered the value of the world's most universal drug, aspirin.