Transport, Technology and Ideology in the Work of Will Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20120906-Ob-Umbrella.Pdf

U m b r e l l a By the same author F ICTION The Quantity Theory of Insanity Cock and Bull My Idea of Fun Grey Area Great Apes The Sweet Smell of Psychosis Tough, Tough Toys for Tough, Tough Boys How the Dead Live Dorian Dr Mukti and Other Tales of Woe The Book of Dave The Butt Liver Walking to Hollywood N on- F ICTION Junk Mail Sore Sites Perfidious Man Feeding Frenzy Psychogeography (with Ralph Steadman) Psycho Too (with Ralph Steadman) U m b r e l l a W i l l S e l f First published in Great Britain 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Will Self The moral right of the author has been asserted No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without written permission from the Publishers except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews ‘Apeman’ by Ray Davies © Copyright 1970 Davray Music Ltd. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing. All rights reserved. Used by permission ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’ (Cassia/Stott) © 1971 Warner Chappell Music Italiana Srl (SIAE). All rights administered by Warner Chappell Overseas Holdings Ltd. All rights reserved ‘Don’t Let It Die’ (Smith) – RAK Publishing Ltd. Licensed courtesy of RAK Publishing Ltd. ‘Sugar Me’ by Barry Green and Lynsey De Paul © Copyright Sony/ATV Music Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. Used by permission ‘Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty’ Words and Music by Fred Godfrey, A. J. Mills & Bennett Scott © 1916. Reproduced by permission of EMI Music Publishing Ltd, London W8 5SW Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright -

"Archived Documents: Issue 2017 2018 Second Edition"

2017-2018 CURRICULUM CATALOG SECOND EDITION Haywood Community College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) to award associate degrees, diplomas, and certificates. The Board of Trustees of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) is responsible for making the final determination on reaffirmation of accreditation based on the findings contained in this committee report, the institution’s response to issues contained in the report, other assessments relevant to the review, and application of the Commission’s policies and procedures. Final interpretation of the Principles of Accreditation and final action on the accreditation status of the institution rest with SACSCOC Board of Trustees. Haywood Community College issues this catalog to furnish prospective students and other interested persons with information about the school and its programs. Announcements contained herein are subject to change without notice and may not be regarded as binding obligations to the College or to the State of North Carolina. Curriculum offerings are subject to sufficient enrollment, with not all courses listed in this catalog being offered each term. Course listings may be altered to meet the needs of the individual program of study or Instruction Division. Upon enrolling at Haywood Community College, students are required to abide by the rules, regulations, and student code of conduct as stated in the most current version of the catalog/handbook, either hardcopy or online. For academic purposes, students must meet program requirements of the catalog of the first semester of attendance, given continued enrollment (fall and spring). If a student drops out a semester (fall or spring), the student follows the catalog requirements for the program of study in the catalog for the year of re-enrollment. -

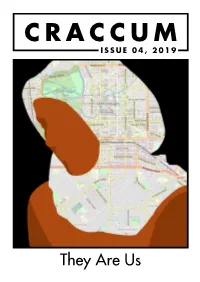

Issue 04 2019

CRACCUM ISSUE 04, 2019 They Are Us 360 International Fair Wednesday 3 April 2019 10am to 2pm OGGB Business School, Level 0 Come along to our 360 International Fair and learn about the overseas opportunities the University has to offer. Learn about: • Semester and year-long exchange Take • Winter and summer schools • Global internship programmes yourself • Partners and providers • Scholarships/funding options global. Michaella, Tainui Semester in the UK auckland.ac.nz/360 [email protected] 04 EDITORIAL 06 NEWS SUMMARY contents 08 NEWS LONGFORM 10 CHRISTCHURCH 16 THINGS DO WHEN FACEBOOK AND INSTAGRAM ARE DOWN 20 ROBINSON 24 REVIEWS 26 SPOTLIGHT 32 LIFESTYLE 32 TINDER HORROR STORIES 34 FOOD REVIEW 36 QUIZ WANT TO CONTRIBUTE? 37 HOROSCOPES Send your ideas to: 38 THE PEOPLE TO BLAME. News [email protected] Features [email protected] Arts [email protected] Community and Lifestyle [email protected] Illustration [email protected] Need feedback on what you’re working on? [email protected] Hot tips on stories [email protected] Your 1 0 0 % s t u d e n t o w n e d u b i q . c o . n z bookstore on campus! 03 editorial. Jokes Aside, Be Kind to One Another BY BAILLEY VERRY Each week Craccum’s esteemed Editor-in-Chief writes their editorial 10 minutes before deadline and this is the product of that. When putting together Craccum, we are one week be- solidarity that the country has already shown is heart- hind the news cycle between the time we go to print and warming. -

Self Destruction Déjà Vu by Ian Hocking 'Very Cool

Will Self : Great Apes : An interview with spike magazine http://www.spikemagazine.com/0597self.php Author Ads: Self Destruction Déjà Vu by Ian Hocking 'Very cool. A new voice in Search now! British SF.' Chris Mitchell finds out why Will Self doesn't give a monkeys Zoe Strachan: Spin Cycle Search now! "A gripping novel, full of twisted Will Self is the man who brought a whole new meaning pyschology and to the phrase "mile high club". Unless you were in a dark, covert obsessions; both murky and dazzling" - Uncut: apathy-induced coma during the run-up to the general Click here election, (or living in another country), you can't have failed to have seen Self's face plastered over the front 666STITCHES by page of every newspaper thanks to the fact that he RGSneddon A recrudescence of snorted heroin on John Major's election jet. Self was combined fables. Occult promptly sacked from his position at The Observer, was Horror. refused to be allowed anywhere near Tony Blair and became the subject of frothing tabloid editorials for days Great Apes Authors: Advertise your afterwards. (For those of you who want to know more, Will Self book here for $30 a month check out LM's report). Buy new or used at - reach 60,000 readers What's New On Spike: This episode ties in neatly with Self's already well-honed media persona - a Suicide: No former heroin addict, enfant terrible of See all books by Compromise - the London literary scene, the English Will Self at David Nobakht successor to American Gonzo journalist "...does a sterling job of chronicling Hunter S. -

PDF Download the Quantity Theory of Insanity

THE QUANTITY THEORY OF INSANITY: REISSUED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Will Self | 288 pages | 29 Sep 2011 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408827451 | English | London, United Kingdom The Quantity Theory of Insanity: Reissued PDF Book Well worth a read, but not Self's best work. Interesting, enjoyable and the type of short story that you think about days after reading. What The Quantity Theory of Insanity is a fun sextet of loosely interconnected stories that tackle several of the themes - madness, medical misbehavior, time, boredom sadly, this freshman feel at fiction doesn't include Self's flair for violence and sexual depravity - which will go on to be the bread and butter of his later works. Check nearby libraries Library. I didn't hate it, but I didn't exactly like it either. There's a story about running into his deceased mother, who is happily alive after death in the London suburbs. Free delivery worldwide. Showing Loading Related Books. He did the music for the South Bank Show documentary on my work in Written in English — pages. Self is known for his satirical, grotesque and fantastic novels and short stories set in seemingly parallel universes. Home Contact us Help Free delivery worldwide. In addition to his fiction, Self has written on a variety subjects from King's Cross crack dens to Aboriginal land rights, for a variety of publications. They should reissue The Penguin John Glashan rather than my doodles. Ward 9 Following this comes a bizarre Kafkaesque tale of an art therapists journey into the world of mental hospital where it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish between doctor and patient. -

A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University The aT ylor Magazine Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections Spring 1996 Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996)" (1996). The Taylor Magazine. 91. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines/91 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aT ylor Magazine by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keeping up with technology on the World Wide Web • The continuing influence ofSamuel Morris • Honor Roll ofDonors - 1995 A MAGAZINE FOR TAYLOR UNIVERSITY ALUMNI AND FRIENDS 1846*1996 SPRING 1996 PRECIS his issue of tlie Taylor Magazine is devoted to the first 50 years of Taylor's existence. Interestingly, I have just finished T reading The Year of Decision - 1846 by Bernard DeVoto. The coincidence is in some ways intentional because a Taylor schoolmate of mine from the 1950's, Dale Murphy, half jokingly recommended that I read the book as I was going to be making so many speeches during our sesquicentennial celebration. As a kind of hobby, I have over the years taken special notice of events concurrent with the college's founding in 1846. The opera Carman was first performed that year and in Germany a man named Bayer discovered the value of the world's most universal drug, aspirin. -

Beth Michael-Fox Thesis for Online

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Present and Accounted For: Making Sense of Death and the Dead in Late Postmodern Culture Bethan Phyllis Michael-Fox ORCID: 0000-0002-9617-2565 Doctor of Philosophy September 2019 This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT STATEMENT No portion of the work referred to in the Thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. I confirm that this Thesis is entirely my own work. I confirm that no work previously submitted for credit has been reused verbatim. Any previously submitted work has been revised, developed and recontextualised relevant to the thesis. I confirm that no material of this thesis has been published in advance of its submission. I confirm that no third party proof-reading or editing has been used in this thesis. 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Alec Charles for his steadfast support and consistent interest in and enthusiasm for my research. I would also like to thank him for being so supportive of my taking maternity leave and for letting me follow him to different institutions. I would like to thank Professor Marcus Leaning for his guidance and the time he has dedicated to me since I have been registered at the University of Winchester. I would also like to thank the University of Winchester’s postgraduate research team and in particular Helen Jones for supporting my transfer process, registration and studies. -

Martin Amis: for My Money, the BBC Got It Right

Mobile site Sign in Register Text larger · smaller About Us Today's paper Zeitgeist Search Television & radio Search News Sport Comment Culture Business Money Life & style Travel Environment TV Video Community Blogs Jobs Culture Television & radio TV and radio blog Series: Shortcuts Previous | Next | Index Martin Amis: for my Money, the BBC got it (26) right Tweet this (72) Comments (55) Martin Amis on why the BBC dramatisation of his novel Money is great television Martin Amis guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 25 May 2010 20.00 BST Article history larger | smaller Television & radio Television Books Martin Amis Series Shortcuts More features On TV & radio Most viewed Zeitgeist Latest Last 24 hours 'Remarkable': Nick Frost as John Self in the BBC dramatisation of Martin Amis's 1. Friends reunited: novel Money. Photograph: Laurence Cendrowicz/BBC which actors should share a TV screen Watching an adaptation of your novel can be a violent experience: again? seeing your old jokes suddenly thrust at you can be alarming. But I started to enjoy Money very quickly, and then I relaxed. 2. What we'll miss about The Bill It's a voice novel, and they're the hardest to film – you've got to use 3. BBC4 pitches to Mad Men fans with new some voiceover to get the voice. But I think the BBC adaptation was drama Rubicon really pretty close to my voice – just the feel of it, the slightly hysterical 4. TV review: Mistresses and E Numbers: An feel of it, which I like. It's a pity one line wasn't used. -

Postgraduate English: Issue 30

Gleghorn Postgraduate English: Issue 30 Postgraduate English www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english ISSN 1756-9761 Issue 30 March 2015 Editors: Sarah Lohmann and Sreemoyee Roy Chowdhury The Paradox of the Memoir in Will Self’s Walking to Hollywood and W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn Martin Gleghorn Durham University 1 Gleghorn Postgraduate English: Issue 30 The paradox of the Memoir in Will Self’s Walking to Hollywood and W. G . Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn Martin Gleghorn Durham University Postgraduate English, Issue 30, March 2015 ‘Will what I have written survive beyond the grave? Will there be anyone to comprehend it in a world the very foundations of which are changed?’1 These are the questions posed by the Vicomte de Chateaubriand (1768-1848), whose Mémoires d'Outre- Tombe (or, Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb) are the subject of one of the most telling digressions within W. G. Sebald’s 1995 work The Rings of Saturn. It is a digression that is so telling because it exposes the reader to the innate fallibility and unreliability of the writer, with Sebald’s narrator surmising that: The chronicler, who was present at these events and is once more recalling what he witnessed, inscribes his experiences, in an act of self-mutilation onto his own body. In the writing, he becomes the martyred paradigm of the fate Providence has in store for us, and, though still alive, is already in the tomb that his memoirs represent.’2 Will Self’s pseudo-autobiographical 2010 triptych Walking to Hollywood is a work heavily influenced by Sebald, from the black-and-white photographs that litter the text, to the thematic links between its final tale, ‘Spurn Head’, and The Rings of Saturn. -

Contemporary British Literature and Urban Space After Thatcher

STATION TO STATION: CONTEMPORARY BRITISH LITERATURE AND URBAN SPACE AFTER THATCHER by KIMBERLY DUFF BA (Hons.), Simon Fraser University, 2001 MA, Simon Fraser University, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2012 © Kimberly Duff, 2012 ABSTRACT “Station to Station: Contemporary British Literature and Urban Space After Thatcher,” examines specific literary representations of public and private urban spaces in late 20th and early 21st-century Great Britain in the context of the shifting tensions that arose from the Thatcherite shift away from state-supported industry toward private ownership, from the welfare state to an American-style free market economy. This project examines literary representations of public and private urban spaces through the following research question: how did the textual mapping of geographical and cultural spaces under Margaret Thatcher uncover the transforming connections of specific British subjects to public/private urban space, national identity, and emergent forms of historical identities and citizenship? And how were the effects of such radical changes represented in post-Thatcher British literary texts that looked back to the British city under Thatcherism? Through an analysis of Thatcher’s progression towards policies of privatization and social reform, this dissertation addresses the Thatcherite “cityspace” (Soja) and what Stuart Hall -

{TEXTBOOK} a Long Days Evening Pdf Free Download

A LONG DAYS EVENING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bilge Karasu | 168 pages | 29 Nov 2012 | City Lights Books | 9780872865914 | English | Monroe, OR, United States A Long Days Evening PDF Book Otherwise, you could end up with evidence of your crying session all over your face, long after the last tear has dried. The holiday was first recognized in the United States as the result of an executive order signed by President Lyndon B. Inevitably, however, the day comes when we all get brave enough to venture toward that mysterious appliance that promises to turn frozen foods into edible treats. For some people, hearing "I love you" will do it. As we all know, however, they must be handled with care in order to avoid certain pitfalls. Here is a prime example of why women tend to live longer than men. Start by enjoying these hilarious photos featuring people who are definitely having a worse day than you are. For others, it was a failed attempt at mimicry. This is funny because Novak had actually been on that show. It sucks to realize that someone has stolen your jewelry, electronics and other valuables, but the sense of violation that comes with being burgled is even worse. Going to bed at the same time is a reliable way to ensure you have time for each other. Because of this, they had to hire actors who could think on their feet. This can cement you as a strong couple and show everyone that you're each other's priority. Unfortunately, the song the cast really wanted got snapped up by another show. -

Read Book \ How the Dead Live

TCWJYUGEFE5W # eBook / How the Dead Live How th e Dead Live Filesize: 2.59 MB Reviews The book is simple in read through better to fully grasp. It is rally exciting throgh looking at period of time. I discovered this publication from my i and dad encouraged this book to find out. (Dr. Dillon Monahan) DISCLAIMER | DMCA ZCBC2JO9K9XC > Doc « How the Dead Live HOW THE DEAD LIVE Paperback. Book Condition: New. Not Signed; How the Dead Live - Booker nominee Will Self's hilarious novel about the aerlife. Scathingly entertaining . ( The Times ). Lily is a colossal heroine, a nighttown Molly Bloom.What begins as a satiric novel of ideas ends as a surprisingly moving elegy . ( Guardian ). Scabrous, vicious and unpleasant in life, Lily Bloom has not been improved by death. She has changed addresses, of course, and now inhabits a basement flat in Dulston - London's borough for those no longer troubled by breathing - but if anything her temperament has worsened. Finding it hard to deal with the (enforced) company of a calcified, pop-obsessed foetus, her dead, foul-mouthed son and three gruesome creatures made of her own unwanted fat, she must find something to do with her time. So how do the dead live? And what happens when they stop being dead? The work of a novelist writing at the height of his powers. It is a horror story, a love-me-do story, a full-frontal assault on the seven deadly sins - and a celebration of them. Lily may be an old cow but she's good company .