London in Space and Time: Peter Ackroyd and Will Self ANDREW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20120906-Ob-Umbrella.Pdf

U m b r e l l a By the same author F ICTION The Quantity Theory of Insanity Cock and Bull My Idea of Fun Grey Area Great Apes The Sweet Smell of Psychosis Tough, Tough Toys for Tough, Tough Boys How the Dead Live Dorian Dr Mukti and Other Tales of Woe The Book of Dave The Butt Liver Walking to Hollywood N on- F ICTION Junk Mail Sore Sites Perfidious Man Feeding Frenzy Psychogeography (with Ralph Steadman) Psycho Too (with Ralph Steadman) U m b r e l l a W i l l S e l f First published in Great Britain 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Will Self The moral right of the author has been asserted No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without written permission from the Publishers except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews ‘Apeman’ by Ray Davies © Copyright 1970 Davray Music Ltd. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing. All rights reserved. Used by permission ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’ (Cassia/Stott) © 1971 Warner Chappell Music Italiana Srl (SIAE). All rights administered by Warner Chappell Overseas Holdings Ltd. All rights reserved ‘Don’t Let It Die’ (Smith) – RAK Publishing Ltd. Licensed courtesy of RAK Publishing Ltd. ‘Sugar Me’ by Barry Green and Lynsey De Paul © Copyright Sony/ATV Music Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. Used by permission ‘Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty’ Words and Music by Fred Godfrey, A. J. Mills & Bennett Scott © 1916. Reproduced by permission of EMI Music Publishing Ltd, London W8 5SW Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright -

Books I've Read Since 2002

Tracy Chevalier – Books I’ve read since 2002 2019 January The Mars Room Rachel Kushner My Sister, the Serial Killer Oyinkan Braithwaite Ma'am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret Craig Brown Liar Ayelet Gundar-Goshen Less Andrew Sean Greer War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (continued) February How to Own the Room Viv Groskop The Doll Factory Elizabeth Macneal The Cut Out Girl Bart van Es The Gifted, the Talented and Me Will Sutcliffe War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (continued) March Late in the Day Tessa Hadley The Cleaner of Chartres Salley Vickers War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (finished!) April Sweet Sorrow David Nicholls The Familiars Stacey Halls Pillars of the Earth Ken Follett May The Mercies Kiran Millwood Hargraves (published Jan 2020) Ghost Wall Sarah Moss Two Girls Down Louisa Luna The Carer Deborah Moggach Holy Disorders Edmund Crispin June Ordinary People Diana Evans The Dutch House Ann Patchett The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Anne Bronte (reread) Miss Garnet's Angel Salley Vickers (reread) Glass Town Isabel Greenberg July American Dirt Jeanine Cummins How to Change Your Mind Michael Pollan A Month in the Country J.L. Carr Venice Jan Morris The White Road Edmund de Waal August Fleishman Is in Trouble Taffy Brodesser-Akner Kindred Octavia Butler Another Fine Mess Tim Moore Three Women Lisa Taddeo Flaubert's Parrot Julian Barnes September The Nickel Boys Colson Whitehead The Testaments Margaret Atwood Mothership Francesca Segal The Secret Commonwealth Philip Pullman October Notes to Self Emilie Pine The Water Cure Sophie Mackintosh Hamnet Maggie O'Farrell The Country Girls Edna O'Brien November Midnight's Children Salman Rushdie (reread) The Wych Elm Tana French On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous Ocean Vuong December Olive, Again Elizabeth Strout* Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead Olga Tokarczuk And Then There Were None Agatha Christie Girl Edna O'Brien My Dark Vanessa Kate Elizabeth Russell *my book of the year. -

Self Destruction Déjà Vu by Ian Hocking 'Very Cool

Will Self : Great Apes : An interview with spike magazine http://www.spikemagazine.com/0597self.php Author Ads: Self Destruction Déjà Vu by Ian Hocking 'Very cool. A new voice in Search now! British SF.' Chris Mitchell finds out why Will Self doesn't give a monkeys Zoe Strachan: Spin Cycle Search now! "A gripping novel, full of twisted Will Self is the man who brought a whole new meaning pyschology and to the phrase "mile high club". Unless you were in a dark, covert obsessions; both murky and dazzling" - Uncut: apathy-induced coma during the run-up to the general Click here election, (or living in another country), you can't have failed to have seen Self's face plastered over the front 666STITCHES by page of every newspaper thanks to the fact that he RGSneddon A recrudescence of snorted heroin on John Major's election jet. Self was combined fables. Occult promptly sacked from his position at The Observer, was Horror. refused to be allowed anywhere near Tony Blair and became the subject of frothing tabloid editorials for days Great Apes Authors: Advertise your afterwards. (For those of you who want to know more, Will Self book here for $30 a month check out LM's report). Buy new or used at - reach 60,000 readers What's New On Spike: This episode ties in neatly with Self's already well-honed media persona - a Suicide: No former heroin addict, enfant terrible of See all books by Compromise - the London literary scene, the English Will Self at David Nobakht successor to American Gonzo journalist "...does a sterling job of chronicling Hunter S. -

Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's Novels

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's Novels Diploma Thesis Brno 2014 Written by: Bc. Jana Neterdová Supervisor: Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Bibliografický záznam Neterdová, Jana. Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's novels. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, Fakulta pedagogická, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2014. 56l. Vedoucí diplomové práce Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Anotace Cílem diplomové práce Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's novels je analyzovat roli historicity v románech daného autora a zhodnotit jakým způsobem a za jakým účelem autor zachází s historickými daty. Práce je rozdělena na dva oddíly, část teoretickou a část analytickou. V teoretické části se práce věnuje definování postmodernismu a postmoderní literatury, protože Peter Ackroyd jako současný autor je považován za představitelé postmodernismu v literatuře. Dále je zde definován pojem historiografická metafikce jako označení pro historický román období postmodernismu. Další část práce je věnována Peteru Ackroydovi a podává základní informace o jeho životě a bližší pohled na jeho dílo, především romány. V analytické části jsou rozebírány čtyři romány: The Lambs of London, The Fall of Troy, The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde a Chatterton. Analýza zahrnuje identifikování prvků, které jsou relevantní pro historicitu románů a vychází z teorie historiografické metafikce. Zabývá se především intertextualitou a způsobem jakým Ackroyd "přepisuje" historii. Poznatky analýzy jsou shrnuty v poslední části práce, ve které jsou vyvozeny závěry, které odpovídají na otázku jak Peter Ackroyd ve svých románech zachází s historií. Abstract Diploma thesis Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's novels aims to analyse the role of historicity in the author's novels and to evaluate how and for what purpose the author deals with history. -

Introduction: Questions of Class in the Contemporary British Novel

Notes Introduction: Questions of Class in the Contemporary British Novel 1. Martin Amis, London Fields (New York: Harmony Books, 1989), 24. 2. The full text of Tony Blair’s 1999 speech can be found at http://news.bbc. co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/460009.stm (accessed on December 9, 2008). 3. Terry Eagleton, After Theory (New York: Perseus Books, 2003), 16. 4. Ibid. 5. Peter Hitchcock, “ ‘They Must Be Represented’: Problems in Theories of Working-Class Representation,” PMLA Special Topic: Rereading Class 115 no. 1 January (2000): 20. Savage, Bagnall, and Longhurst have also pointed out that “Over the past twenty-five years, this sense that the working class ‘matters’ has ebbed. It is now difficult to detect sustained research interest in the nature of working class culture” (97). 6. Gary Day, Class (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), 202. This point is also echoed by Ebert and Zavarzadeh: “By advancing singularity, hetero- geneity, anti-totality, and supplementarity, for instance, deconstruction has, among other things, demolished ‘history’ itself as an articulation of class relations. In doing so, it has constructed a cognitive environment in which the economic interests of capital are seen as natural and not the effect of a particular historical situation. Deconstruction continues to produce some of the most effective discourses to normalize capitalism and contribute to the construction of a capitalist-friendly cultural common sense . .” (8). 7. Slavoj Žižek, In Defence of Lost Causes (London and New York: Verso, 2008), 404–405 (Hereafter, Lost Causes). 8. Andrew Milner, Class (London: Sage, 1999), 9. 9. Gavin Keulks, ed., Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 73. -

Title the First Female British Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy

Title The first female British poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy : a biographical sketch and interpretation of her poem 'The Thames, London 2012' Sub Title 英国初の女性桂冠詩人, キャロル・アン・ダフィーの経歴と作品, 「テムズ川, ロンドン2012年」の考察 Author 富田, 裕子(Tomida, Hiroko) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication year 2016 Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 言語・文化・コミュニケーション (Language, culture and communication). No.47 (2016. ) ,p.39- 59 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL http://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=AN1003 2394-20160331-0039 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) The First Female British Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy —a Biographical Sketch and Interpretation of her Poem ‘The Thames, London 2012’ Hiroko Tomida Introduction Although the name of Carol Ann Duffy has been known to the British public since she was appointed Britain’s Poet Laureate in May 2009, she remains an obscure figure outside Britain, especially in Japan.1 Her radio and television interviews are accessible, and the collections of her poems are easily obtainable. However, there are only a few books, exploring her poetry from a wide range of literary and theoretical perspectives.2 The rest of the publications are short articles, which appeared mostly in literary magazines and newspapers.3 Indeed her biographical sketches and analyses of her poems, especially the recent ones, are very limited in number. Therefore the main objectives of this article are to introduce her biography and to analyse one of her recent poems relating to British history. This article will be divided into two sections. In the first part, Duffy’s upbringing, and family and educational backgrounds, and her careers as a poet, playwright, literary critic and an academic will be examined. -

The Image of London in Peter Ackroyd's Thames: Sacred

T. C. SELÇUK UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF LETTERS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE THE IMAGE OF LONDON IN PETER ACKROYD’S THAMES: SACRED RIVER AND THE LAMBS OF LONDON Hava VURAL MASTER’S THESIS SUPERVISOR Assist. Prof. Ayşe Gülbün ONUR Konya – 2014 T. C. SELÇUK UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF LETTERS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE THE IMAGE OF LONDON IN PETER ACKROYD’S THAMES: SACRED RIVER AND THE LAMBS OF LONDON Hava VURAL MASTER’S THESIS SUPERVISOR Assist. Prof. Ayşe Gülbün ONUR Konya – 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Bilimsel Etik Sayfası 1……….………………………….……………………………i Bilimsel Etik Sayfası 2………...……………………………………………………..ii Tez Kabul Formu…………………………….………………………………………iii Teşekkür /Acknowledgements…..……………………………………………….......iv Özet ………………………..….………………………………………………….…..v Abstract …………….…….…………...……………………………………………..vi INTRODUCTION………………….……………………………………………….1 CHAPTER I: PETER ACKROYD 1.1. Biographical Details of Peter Ackroyd………………………………..….…4 1.2. Social and Literary Background to His Literary Career……………...……12 CHAPTER II: THE IMAGE OF LONDON IN THAMES: SACRED RIVER 2. 1. Introduction to Thames: Sacred River………...…………………………...15 2. 2. The Thames As A Character………..………..…..………………………...16 2. 2. 1. The Thames As A Historical Character……………………………..18 2. 2. 2. The Thames As A Cultural Character……………………………….23 2. 2. 3. The Thames As A Poetic Character.……………………………...…33 2. 2. 4. The Thames As A Fictional Character……………………………....39 2. 2. 5. The Thames As A Holy Character………………..…….......……….45 CHAPTER III: THEORETICAL BACKGROUND TO THE LAMBS OF LONDON……………………………………………………………………………49 3.1. Rewriting, Parody, and Pastiche…………………………………………….52 3. 2. The City: London…………………………………………………………...55 CHAPTER IV: THE LAMBS OF LONDON 4.1. Introduction to The Lambs of London: A Brief Summary………………..…61 4.2. -

Martin Amis: for My Money, the BBC Got It Right

Mobile site Sign in Register Text larger · smaller About Us Today's paper Zeitgeist Search Television & radio Search News Sport Comment Culture Business Money Life & style Travel Environment TV Video Community Blogs Jobs Culture Television & radio TV and radio blog Series: Shortcuts Previous | Next | Index Martin Amis: for my Money, the BBC got it (26) right Tweet this (72) Comments (55) Martin Amis on why the BBC dramatisation of his novel Money is great television Martin Amis guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 25 May 2010 20.00 BST Article history larger | smaller Television & radio Television Books Martin Amis Series Shortcuts More features On TV & radio Most viewed Zeitgeist Latest Last 24 hours 'Remarkable': Nick Frost as John Self in the BBC dramatisation of Martin Amis's 1. Friends reunited: novel Money. Photograph: Laurence Cendrowicz/BBC which actors should share a TV screen Watching an adaptation of your novel can be a violent experience: again? seeing your old jokes suddenly thrust at you can be alarming. But I started to enjoy Money very quickly, and then I relaxed. 2. What we'll miss about The Bill It's a voice novel, and they're the hardest to film – you've got to use 3. BBC4 pitches to Mad Men fans with new some voiceover to get the voice. But I think the BBC adaptation was drama Rubicon really pretty close to my voice – just the feel of it, the slightly hysterical 4. TV review: Mistresses and E Numbers: An feel of it, which I like. It's a pity one line wasn't used. -

Postgraduate English: Issue 30

Gleghorn Postgraduate English: Issue 30 Postgraduate English www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english ISSN 1756-9761 Issue 30 March 2015 Editors: Sarah Lohmann and Sreemoyee Roy Chowdhury The Paradox of the Memoir in Will Self’s Walking to Hollywood and W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn Martin Gleghorn Durham University 1 Gleghorn Postgraduate English: Issue 30 The paradox of the Memoir in Will Self’s Walking to Hollywood and W. G . Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn Martin Gleghorn Durham University Postgraduate English, Issue 30, March 2015 ‘Will what I have written survive beyond the grave? Will there be anyone to comprehend it in a world the very foundations of which are changed?’1 These are the questions posed by the Vicomte de Chateaubriand (1768-1848), whose Mémoires d'Outre- Tombe (or, Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb) are the subject of one of the most telling digressions within W. G. Sebald’s 1995 work The Rings of Saturn. It is a digression that is so telling because it exposes the reader to the innate fallibility and unreliability of the writer, with Sebald’s narrator surmising that: The chronicler, who was present at these events and is once more recalling what he witnessed, inscribes his experiences, in an act of self-mutilation onto his own body. In the writing, he becomes the martyred paradigm of the fate Providence has in store for us, and, though still alive, is already in the tomb that his memoirs represent.’2 Will Self’s pseudo-autobiographical 2010 triptych Walking to Hollywood is a work heavily influenced by Sebald, from the black-and-white photographs that litter the text, to the thematic links between its final tale, ‘Spurn Head’, and The Rings of Saturn. -

Finch Åbo Akademi University [email protected]

Book Reviews 223 Sebastian Groes (2011)The Making of London: London in Contemporary Literature, with photographs by Sarah Baxter. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 309pp., ISBN: 9780230348363. Sebastian Groes argues that the writers he considers in this book have started a counter-cultural project in the current era of British history, which he defines as that of ‘Long Thatcherism’ (Groes, 2011, p.43). This project aims, using literary techniques, to ‘resist and reverse the increasing fragmentation of the metropolis’ (p.251). Before 1975, the year in which Margaret Thatcher became leader of the UK Conservative Party, Groes sees British imperial decline reflected in the physical decay of London; since then, economic resurgence under Thatcher and Tony Blair, in a period addicted to political spin and rhetoric, has reinvented London as a simulacrum capital of fun and leisure (p. 23). The arts, including fiction, Groes claims, ‘particularly allow us to see behind the surface of material things and events because they transfigure the life of the city and its inhabitants’ (p. 4). As such, his book makes a bold case for the importance of fiction in developing understandings of contemporary urban and post-urban environments worldwide. The book’s theoretical framework includes names familiar to students of contemporary cultural theory and radical geographies – Mikhail Bakhtin, Jean Baudrillard, Michel de Certeau, Mike Davis, Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, David Harvey, Henri Lefebvre, Edward Soja – alongside creative writers and thinkers who could be considered Romantic, realist, modernist and postmodernist masters: William Wordsworth, Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad, Sigmund Freud, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Milan Kundera, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. -

A Social Identity Model of Riot Diffusion: from Injustice to Empowerment in the 2011 London Riots

A social identity model of riot diffusion: from injustice to empowerment in the 2011 London riots Article (Supplemental Material) Drury, John, Stott, Clifford, Ball, Roger, Reicher, Stephen, Neville, Fergus, Bell, Linda, Biddlestone, Mikey, Choudhury, Sanjeedah, Lovell, Max and Ryan, Caoimhe (2020) A social identity model of riot diffusion: from injustice to empowerment in the 2011 London riots. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50 (3). pp. 646-661. ISSN 0046-2772 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/89133/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

2D3bc7b445de88d93e24c0bab4

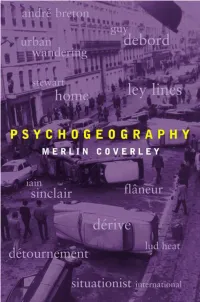

PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 2 Other titles in this series by the same author: London Writing PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 3 Psychogeography MERLIN COVERLEY POCKET ESSENTIALS PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 4 First published in 2006 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts,AL5 1XJ www.pocketessentials.com © Merlin Coverley 2006 The right of Merlin Coverley to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publishers. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 904048 61 7 EAN 978 1 904048 61 9 24681097531 Typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPD Ltd, Ebbw Vale,Wales PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 5 To C at h e r i n e PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 6 PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 7 Contents Introduction 9 1: London and the Visionary Tradition 31 Daniel Defoe and the Re-Imagining of London; William Blake and the Visionary Tradition; Thomas De Quincey and the Origins of the Urban Wanderer; Robert Louis Stevenson and the Urban Gothic; Arthur Machen and the Art of Wandering;