Peter Ackroyd, Blake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Books I've Read Since 2002

Tracy Chevalier – Books I’ve read since 2002 2019 January The Mars Room Rachel Kushner My Sister, the Serial Killer Oyinkan Braithwaite Ma'am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret Craig Brown Liar Ayelet Gundar-Goshen Less Andrew Sean Greer War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (continued) February How to Own the Room Viv Groskop The Doll Factory Elizabeth Macneal The Cut Out Girl Bart van Es The Gifted, the Talented and Me Will Sutcliffe War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (continued) March Late in the Day Tessa Hadley The Cleaner of Chartres Salley Vickers War and Peace Leo Tolstoy (finished!) April Sweet Sorrow David Nicholls The Familiars Stacey Halls Pillars of the Earth Ken Follett May The Mercies Kiran Millwood Hargraves (published Jan 2020) Ghost Wall Sarah Moss Two Girls Down Louisa Luna The Carer Deborah Moggach Holy Disorders Edmund Crispin June Ordinary People Diana Evans The Dutch House Ann Patchett The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Anne Bronte (reread) Miss Garnet's Angel Salley Vickers (reread) Glass Town Isabel Greenberg July American Dirt Jeanine Cummins How to Change Your Mind Michael Pollan A Month in the Country J.L. Carr Venice Jan Morris The White Road Edmund de Waal August Fleishman Is in Trouble Taffy Brodesser-Akner Kindred Octavia Butler Another Fine Mess Tim Moore Three Women Lisa Taddeo Flaubert's Parrot Julian Barnes September The Nickel Boys Colson Whitehead The Testaments Margaret Atwood Mothership Francesca Segal The Secret Commonwealth Philip Pullman October Notes to Self Emilie Pine The Water Cure Sophie Mackintosh Hamnet Maggie O'Farrell The Country Girls Edna O'Brien November Midnight's Children Salman Rushdie (reread) The Wych Elm Tana French On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous Ocean Vuong December Olive, Again Elizabeth Strout* Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead Olga Tokarczuk And Then There Were None Agatha Christie Girl Edna O'Brien My Dark Vanessa Kate Elizabeth Russell *my book of the year. -

Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's Novels

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's Novels Diploma Thesis Brno 2014 Written by: Bc. Jana Neterdová Supervisor: Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Bibliografický záznam Neterdová, Jana. Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's novels. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, Fakulta pedagogická, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2014. 56l. Vedoucí diplomové práce Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Anotace Cílem diplomové práce Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's novels je analyzovat roli historicity v románech daného autora a zhodnotit jakým způsobem a za jakým účelem autor zachází s historickými daty. Práce je rozdělena na dva oddíly, část teoretickou a část analytickou. V teoretické části se práce věnuje definování postmodernismu a postmoderní literatury, protože Peter Ackroyd jako současný autor je považován za představitelé postmodernismu v literatuře. Dále je zde definován pojem historiografická metafikce jako označení pro historický román období postmodernismu. Další část práce je věnována Peteru Ackroydovi a podává základní informace o jeho životě a bližší pohled na jeho dílo, především romány. V analytické části jsou rozebírány čtyři romány: The Lambs of London, The Fall of Troy, The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde a Chatterton. Analýza zahrnuje identifikování prvků, které jsou relevantní pro historicitu románů a vychází z teorie historiografické metafikce. Zabývá se především intertextualitou a způsobem jakým Ackroyd "přepisuje" historii. Poznatky analýzy jsou shrnuty v poslední části práce, ve které jsou vyvozeny závěry, které odpovídají na otázku jak Peter Ackroyd ve svých románech zachází s historií. Abstract Diploma thesis Historicity in Peter Ackroyd's novels aims to analyse the role of historicity in the author's novels and to evaluate how and for what purpose the author deals with history. -

Introduction: Questions of Class in the Contemporary British Novel

Notes Introduction: Questions of Class in the Contemporary British Novel 1. Martin Amis, London Fields (New York: Harmony Books, 1989), 24. 2. The full text of Tony Blair’s 1999 speech can be found at http://news.bbc. co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/460009.stm (accessed on December 9, 2008). 3. Terry Eagleton, After Theory (New York: Perseus Books, 2003), 16. 4. Ibid. 5. Peter Hitchcock, “ ‘They Must Be Represented’: Problems in Theories of Working-Class Representation,” PMLA Special Topic: Rereading Class 115 no. 1 January (2000): 20. Savage, Bagnall, and Longhurst have also pointed out that “Over the past twenty-five years, this sense that the working class ‘matters’ has ebbed. It is now difficult to detect sustained research interest in the nature of working class culture” (97). 6. Gary Day, Class (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), 202. This point is also echoed by Ebert and Zavarzadeh: “By advancing singularity, hetero- geneity, anti-totality, and supplementarity, for instance, deconstruction has, among other things, demolished ‘history’ itself as an articulation of class relations. In doing so, it has constructed a cognitive environment in which the economic interests of capital are seen as natural and not the effect of a particular historical situation. Deconstruction continues to produce some of the most effective discourses to normalize capitalism and contribute to the construction of a capitalist-friendly cultural common sense . .” (8). 7. Slavoj Žižek, In Defence of Lost Causes (London and New York: Verso, 2008), 404–405 (Hereafter, Lost Causes). 8. Andrew Milner, Class (London: Sage, 1999), 9. 9. Gavin Keulks, ed., Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 73. -

Title the First Female British Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy

Title The first female British poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy : a biographical sketch and interpretation of her poem 'The Thames, London 2012' Sub Title 英国初の女性桂冠詩人, キャロル・アン・ダフィーの経歴と作品, 「テムズ川, ロンドン2012年」の考察 Author 富田, 裕子(Tomida, Hiroko) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication year 2016 Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 言語・文化・コミュニケーション (Language, culture and communication). No.47 (2016. ) ,p.39- 59 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL http://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=AN1003 2394-20160331-0039 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) The First Female British Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy —a Biographical Sketch and Interpretation of her Poem ‘The Thames, London 2012’ Hiroko Tomida Introduction Although the name of Carol Ann Duffy has been known to the British public since she was appointed Britain’s Poet Laureate in May 2009, she remains an obscure figure outside Britain, especially in Japan.1 Her radio and television interviews are accessible, and the collections of her poems are easily obtainable. However, there are only a few books, exploring her poetry from a wide range of literary and theoretical perspectives.2 The rest of the publications are short articles, which appeared mostly in literary magazines and newspapers.3 Indeed her biographical sketches and analyses of her poems, especially the recent ones, are very limited in number. Therefore the main objectives of this article are to introduce her biography and to analyse one of her recent poems relating to British history. This article will be divided into two sections. In the first part, Duffy’s upbringing, and family and educational backgrounds, and her careers as a poet, playwright, literary critic and an academic will be examined. -

The Image of London in Peter Ackroyd's Thames: Sacred

T. C. SELÇUK UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF LETTERS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE THE IMAGE OF LONDON IN PETER ACKROYD’S THAMES: SACRED RIVER AND THE LAMBS OF LONDON Hava VURAL MASTER’S THESIS SUPERVISOR Assist. Prof. Ayşe Gülbün ONUR Konya – 2014 T. C. SELÇUK UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF LETTERS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE THE IMAGE OF LONDON IN PETER ACKROYD’S THAMES: SACRED RIVER AND THE LAMBS OF LONDON Hava VURAL MASTER’S THESIS SUPERVISOR Assist. Prof. Ayşe Gülbün ONUR Konya – 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Bilimsel Etik Sayfası 1……….………………………….……………………………i Bilimsel Etik Sayfası 2………...……………………………………………………..ii Tez Kabul Formu…………………………….………………………………………iii Teşekkür /Acknowledgements…..……………………………………………….......iv Özet ………………………..….………………………………………………….…..v Abstract …………….…….…………...……………………………………………..vi INTRODUCTION………………….……………………………………………….1 CHAPTER I: PETER ACKROYD 1.1. Biographical Details of Peter Ackroyd………………………………..….…4 1.2. Social and Literary Background to His Literary Career……………...……12 CHAPTER II: THE IMAGE OF LONDON IN THAMES: SACRED RIVER 2. 1. Introduction to Thames: Sacred River………...…………………………...15 2. 2. The Thames As A Character………..………..…..………………………...16 2. 2. 1. The Thames As A Historical Character……………………………..18 2. 2. 2. The Thames As A Cultural Character……………………………….23 2. 2. 3. The Thames As A Poetic Character.……………………………...…33 2. 2. 4. The Thames As A Fictional Character……………………………....39 2. 2. 5. The Thames As A Holy Character………………..…….......……….45 CHAPTER III: THEORETICAL BACKGROUND TO THE LAMBS OF LONDON……………………………………………………………………………49 3.1. Rewriting, Parody, and Pastiche…………………………………………….52 3. 2. The City: London…………………………………………………………...55 CHAPTER IV: THE LAMBS OF LONDON 4.1. Introduction to The Lambs of London: A Brief Summary………………..…61 4.2. -

Finch Åbo Akademi University [email protected]

Book Reviews 223 Sebastian Groes (2011)The Making of London: London in Contemporary Literature, with photographs by Sarah Baxter. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 309pp., ISBN: 9780230348363. Sebastian Groes argues that the writers he considers in this book have started a counter-cultural project in the current era of British history, which he defines as that of ‘Long Thatcherism’ (Groes, 2011, p.43). This project aims, using literary techniques, to ‘resist and reverse the increasing fragmentation of the metropolis’ (p.251). Before 1975, the year in which Margaret Thatcher became leader of the UK Conservative Party, Groes sees British imperial decline reflected in the physical decay of London; since then, economic resurgence under Thatcher and Tony Blair, in a period addicted to political spin and rhetoric, has reinvented London as a simulacrum capital of fun and leisure (p. 23). The arts, including fiction, Groes claims, ‘particularly allow us to see behind the surface of material things and events because they transfigure the life of the city and its inhabitants’ (p. 4). As such, his book makes a bold case for the importance of fiction in developing understandings of contemporary urban and post-urban environments worldwide. The book’s theoretical framework includes names familiar to students of contemporary cultural theory and radical geographies – Mikhail Bakhtin, Jean Baudrillard, Michel de Certeau, Mike Davis, Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, David Harvey, Henri Lefebvre, Edward Soja – alongside creative writers and thinkers who could be considered Romantic, realist, modernist and postmodernist masters: William Wordsworth, Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad, Sigmund Freud, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Milan Kundera, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. -

2D3bc7b445de88d93e24c0bab4

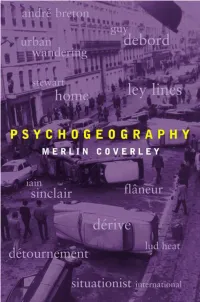

PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 2 Other titles in this series by the same author: London Writing PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 3 Psychogeography MERLIN COVERLEY POCKET ESSENTIALS PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 4 First published in 2006 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts,AL5 1XJ www.pocketessentials.com © Merlin Coverley 2006 The right of Merlin Coverley to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publishers. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 904048 61 7 EAN 978 1 904048 61 9 24681097531 Typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPD Ltd, Ebbw Vale,Wales PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 5 To C at h e r i n e PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 6 PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 7 Contents Introduction 9 1: London and the Visionary Tradition 31 Daniel Defoe and the Re-Imagining of London; William Blake and the Visionary Tradition; Thomas De Quincey and the Origins of the Urban Wanderer; Robert Louis Stevenson and the Urban Gothic; Arthur Machen and the Art of Wandering; -

SAVU, LAURA E., Ph.D. Postmortem Postmodernists: Authorship and Cultural Revisionism in Late Twentieth-Century Narrative. (2006) Directed by Dr

SAVU, LAURA E., Ph.D. Postmortem Postmodernists: Authorship and Cultural Revisionism in Late Twentieth-Century Narrative. (2006) Directed by Dr. Keith Cushman. 331 pp The past three decades have witnessed an explosion of narratives in which the literary greats are brought back to life, reanimated and bodied forth in new textual bodies. In the works herein examined—Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower, Peter Ackroyd’s The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde and Chatterton, Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs, Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, Colm Toíbín’s The Master, and Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence—the obsession with biography spills over into fiction, the past blends with the present, history with imagination. Thus they articulate, reflect on, and can be read through postmodern concerns about language and representation, authorship and creativity, narrative and history, rewriting and the posthumous. As I argue, late twentieth-century fiction “postmodernizes” romantic and modern authors not only to understand them better, but also to understand itself in relation to a past (literary tradition, aesthetic paradigms, cultural formations, etc.) that has not really passed. More specifically, these works project a postmodern understanding of the author as a historically and culturally contingent subjectivity constructed along the lines of gender, sexual orientation, class, and nationality. The immediate implications of my argument are twofold, and they emerge as the common threads linking the chapters that make up this study. First, to make a case for the return of the author into the contemporary literary space is to acknowledge that the postmodern, its antihumanist bias notwithstanding, does not discount the human. -

Representations of London in Peter Ackroyd's Fiction

“THE MYSTICAL CITY UNIVERSAL” : REPRESENTATIONS OF LONDON IN PETER ACKROYD’S FICTION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY BERKEM GÜRENCİ SAĞLAM IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH LITERATURE OCTOBER 2007 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ____________________ Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ____________________ Prof. Dr. Wolf König Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________ Prof. Dr. Nursel İçöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Nursel İçöz (METU, FLE) ____________________ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Margaret Sönmez (METU, FLE) ____________________ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Nazan Tutaş (Ankara U, DTCF) ____________________ Dr. Deniz Arslan (METU, FLE) ____________________ Dr. Özlem Uzundemir (Başkent U, FEF) ____________________ I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Surname: Berkem Gürenci Sağlam Signature: iii ABSTRACT “THE MYSTICAL CITY UNIVERSAL” : REPRESENTATIONS OF LONDON IN PETER ACKROYD’S FICTION Gürenci Sağlam, Berkem Ph.D., Department of English Literature Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Nursel İçöz October 2007 Most of Peter Ackroyd’s work takes place in London, and the city can be said to be a unifying element in his work. -

Penguin Classics

PENGUIN CLASSICS A Complete Annotated Listing www.penguinclassics.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world, providing readers with a library of the best works from around the world, throughout history, and across genres and disciplines. We focus on bringing together the best of the past and the future, using cutting-edge design and production as well as embracing the digital age to create unforgettable editions of treasured literature. Penguin Classics is timeless and trend-setting. Whether you love our signature black- spine series, our Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions, or our eBooks, we bring the writer to the reader in every format available. With this catalog—which provides complete, annotated descriptions of all books currently in our Classics series, as well as those in the Pelican Shakespeare series—we celebrate our entire list and the illustrious history behind it and continue to uphold our established standards of excellence with exciting new releases. From acclaimed new translations of Herodotus and the I Ching to the existential horrors of contemporary master Thomas Ligotti, from a trove of rediscovered fairytales translated for the first time in The Turnip Princess to the ethically ambiguous military exploits of Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, there are classics here to educate, provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers of all interests and inclinations. We hope this catalog will inspire you to pick up that book you’ve always been meaning to read, or one you may not have heard of before. To receive more information about Penguin Classics or to sign up for a newsletter, please visit our Classics Web site at www.penguinclassics.com. -

Rebellion: the History of England from James I to the Glorious Revolution Pdf, Epub, Ebook

REBELLION: THE HISTORY OF ENGLAND FROM JAMES I TO THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Ackroyd | 512 pages | 08 Sep 2015 | St. Martin's Griffin | 9781250070241 | English | United States Rebellion: The History of England from James I to the Glorious Revolution PDF Book Oct 10, David added it Shelves: new-in As well as taking in all of the above, Ackroyd also makes sure to include what life was like in general during these years, encompassing the changing fashions, leaps in architecture and scientific knowledge thanks to figures like Christopher Wren and Isaac Newton, and the changing moods in music and literature from the likes of Shakespeare, John Milton and Samuel Pepys. William in private conversation with Halifax, Danby, Shrewsbury, Lord Winchester and Lord Mordaunt made it clear that they could either accept him as king or deal with the Whigs without his military presence, for then he would leave for the Republic. News of James's flight led to celebrations and anti- Catholic riots in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Because, let's be honest, this is a gem: "At the end of the discussion Cromwell, in one of those fits of boisterousness or hysteria that punctuated his career, threw a cushion at one of the protagonists, Edmund Ludlow, before running downstairs; Ludlow pursued him, and in turn pummelled him with a cushion. That is perhaps too harsh; Cecil had so great a political intelligence that he may qualify as a statesman. Totally fascinating look into the Stuarts and the 17th century. On the road. In Rebellion, he continues his dazzling account of the history of England, beginning with the progress south of the Scottish king, James VI, who on the death of Elizabeth I became the first Stuart king of England, and ending with the deposition and flight into exile of his g Peter Ackroyd has been praised as one of the greatest living chroniclers of Britain and its people. -

Here Is a List of Popular British Authors That Can Be Considered for the Sample; Any Other Current British Authors Can Also Be Included

Here is a list of popular British authors that can be considered for the sample; any other current British authors can also be included. 1. Peter Ackroyd 2. Elizabeth Adler 3. Cecelia Ahern 4. Monica Ali 5. Martin Amis 6. Jeffrey Archer 7. Kate Atkinson 8. John Banville 9. Clive Barker 10. Nicola Barker 11. Pat Barker 12. Julian Barnes 13. M. C. Beaton 14. Peter Benson 15. Mark Billingham 16. Maeve Binchy 17. Rhys Bowen 18. William Boyd 19. Barbara Taylor Bradford 20. Anita Brookner 21. Hester Browne 22. Ken Bruen 23. Stella Cameron 24. John le Carre 25. Lee Child 26. P F Chisholm 27. Jonathan Coe 28. Rowan Coleman 29. Jackie Collins 30. John Connolly 31. Bernard Cornwell 32. Jim Crace 33. Lindsey Davis 34. Emma Donoghue 35. Ruth Downie 36. Sarah Dunant 37. Helen Dunmore 38. Anne Enright 39. Harriet Evans 40. Roopa Farooki 41. Sebastian Faulks 42. Jasper Fforde 43. Helen Fielding 44. Ken Follett 45. Neil Gaiman 46. Jane Gardam 47. Jane Green 48. Sarah Hall 49. Joanne Harris 50. Robert Harris 51. Nick Hornby 52. Conn Iggulden 53. Kazuo Ishiguro 54. Cathy Kelly A. L. Kennedy 55. Marian Keyes 56. Sophie Kinsella 57. Doris Lessing 58. Hilary Mantel 59. Sujata Massey 60. Simon Mawer 61. Peter Mayle 62. Patrick McCabe 63. Ian McEwan 64. Adrian McKinty 65. Anna McPartlin 66. Michael J. Merry 67. Rosalind Miles 68. Robert Morgan 69. Melissa Nathan 70. Elizabeth Noble 71. Helen Oyeyemi 72. Adele Parks 73. Anne Perry 74. Caryl Phillips 75. Robin Pilcher 76. Terry Pratchett 77.