The Pennsylvania State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Writing Homework for July 25

Writing Homework for July 25 Below are some descriptions of movies coming to a theatre near you (taken from the Rotten Tomatoes web site). Choose at least five to render into Irish, more if you would like. Do Not Be Too Literal! Break longer sentences into separate sentences, put information in a different order, all you need to do it produce a recognizable synopsis of the film. Take liberties! Leave out details, get the basics. ------------- The Secret Life of Pets. For their fifth fully-animated feature-film collaboration, Illumination Entertainment and Universal Pictures present The Secret Life of Pets, a comedy about the lives our pets lead after we leave for work or school each day. Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates. Hard-partying brothers Mike (Adam Devine) and Dave (Zac Efron) place an online ad to find the perfect dates (Anna Kendrick, Aubrey Plaza) for their sister's Hawaiian wedding. Hoping for a wild getaway, the boys instead find themselves outsmarted and out-partied by the uncontrollable duo. Captain Fantastic. Deep in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, isolated from society, a devoted father (Viggo Mortensen) dedicates his life to transforming his six you g children into extraordinary adults. But when a tragedy strikes the family, they are forced to leave this self- created paradise and begin a journey into the outside world that challenges his idea of what it means to be a parent and brings into question everything he's taught them. Cell. Stephen King's best-selling novel is brought to terrifying life in this mind-blowing thriller starring John Cusack and Samuel L. -

Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~

KEEPING UP WITH THE JONESES: SOCIOECONOMIC CLASS REPRESENTATION IN SITCOMS by ALEXANDRA HICKS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2014 A• Abstracto( the Thesis of Alexandra Hicks for 1he degree ofBachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be talcen June, 2014 Title: Keeping Up With the Jonescs: Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~ This thesis examines the representation of socioeconomic class in situation comedies. Through the influence of the advertising industiy, situation comedies (sitcoms) have developed a pattem throughout history of misrepresenting ~ial class, which is made evident by their portrayals ofdifferent races, genders, and professions. To rectify the IKk ofprevious studies on modem comedies, this study analyzes socioeconomic class representation on sitcoms that have aired in the last JS years by taking a sample ofseven shows and comparing the estimated cost of characters' residences to the amount of money they would likely earn in their given profession. 1be study showed that modem situation comedies misrepresent socioeconomic class by portraying characters living in residences well beyond what they could afford in real life. Accurate demonstration ofsocioeconomic class on television is imperative be<:ause images presented on television genuinely influence viewers• perceptions of reality. Inaccurate portrayals ofclass could cause audiences to develop distorted views ofmember.; of socioeconomic classes and themselves. u Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Debra Merskin for inspiring me to examine television in an in-depth and critical manner. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

CONTACT: Robin Mesger the Lippin Group 323/965-1990 FOR

CONTACT: Robin Mesger The Lippin Group 323/965-1990 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 14, 2002 2002 PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS The Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS) tonight (Saturday, September 14, 2002) presented Emmys in 61 categories for programs and individual achievements at the 54th Annual Emmy Awards Presentation at the Shrine Auditorium. Included among the presentations were Emmy Awards for the following previously announced categories: Outstanding Achievement in Animation and Outstanding Voice-Over Performance. ATAS Chairman & CEO Bryce Zabel presided over the awards ceremony assisted by a lineup of major television stars as presenters. The awards, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Programs Individuals Total HBO 0 16 16 NBC 1 14 15 ABC 0 5 5 A&E 1 4 5 FOX 1 4 5 CBS 1 3 4 DISC 1 3 4 UPN 0 2 2 TNT 0 2 2 MTV 1 0 1 NICK 1 0 1 PBS 1 0 1 SHO 0 1 1 WB 0 1 1 Emmys in 27 other categories will be presented at the 2002 Primetime Emmy Awards telecast on Sunday, September 22, 2002, 8:00 p.m. – conclusion, ET/PT) over the NBC Television Network at the Shrine Auditorium. A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached, The final page of the attached list includes a recap of all programs with multiple awards. For further information, see www.emmys.tv. To receive TV Academy news releases via electronic mail, please address your request to [email protected] or [email protected]. -

Stageoflife.Com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV

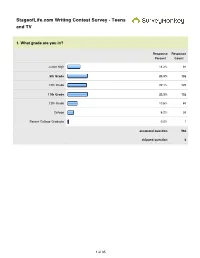

StageofLife.com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV 1. What grade are you in? Response Response Percent Count Junior High 14.3% 81 9th Grade 23.3% 132 10th Grade 22.1% 125 11th Grade 23.3% 132 12th Grade 10.6% 60 College 6.2% 35 Recent College Graduate 0.2% 1 answered question 566 skipped question 0 1 of 35 2. How many TV shows (30 - 60 minutes) do you watch in an average week during the school year? Response Response Percent Count 20+ (approx 3 shows per day) 21.7% 123 14 (approx 2 shows per day) 11.3% 64 10 (approx 1.5 shows per day) 9.0% 51 7 (approx. 1 show per day) 15.7% 89 3 (approx. 1 show every other 25.8% 146 day) 1 (you watch one show a week) 14.5% 82 0 (you never watch TV) 1.9% 11 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3. Do you watch TV before you leave for school in the morning? Response Response Percent Count Yes 15.7% 89 No 84.3% 477 answered question 566 skipped question 0 2 of 35 4. Do you have a TV in your bedroom? Response Response Percent Count Yes 38.7% 219 No 61.3% 347 answered question 566 skipped question 0 5. Do you watch TV with your parents? Response Response Percent Count Yes 60.6% 343 No 39.4% 223 If yes, which show(s) do you watch as a family? 302 answered question 566 skipped question 0 6. Overall, do you think TV is too violent? Response Response Percent Count Yes 28.3% 160 No 71.7% 406 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3 of 35 7. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

Your September Tv 2012 Premiere Calendar

YOUR SEPTEMBER TV 2012 PREMIERE CALENDAR 02 03 05 06 07 08 Coma, 9PM A&E Switched at Birth, 8PM ABC Family NFL Kicko Special: 2012 MTV Video Stand Up to Cancer Cowboys at Giants, Music Awards, Special, 8PM ABC, CBS, 7:30PM NBC 8PM MTV The CW, NBC and FOX 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 The Voice, The X Factor, 8PM NBC 8PM FOX Go On, Shark Tank, 9PM NBC 8PM ABC The New Normal, Grimm, 9:30PM NBC 9PM NBC Parenthood, Primetime: What Would 10PM NBC You Do? 9PM ABC Seth MacFarlane hosts Saturday Night Live with Sons of Anarchy, Guys with Kids, Glee, 20/20, musical guest Frank 10PM FX 10PM NBC 9PM FOX 10PM ABC Ocean, 11:35PM NBC Joseph Gordon- 16 17 19 20 21 Levitt hosts SNL with musical guest SNL Election Special, Haven, Mumford & Sons, 8PM NBC 10PM Syfy 11:35PM NBC Up all Night, 8:30PM NBC Boardwalk Bones, Empire, 8PM FOX The Oce, 9PM HBO 9PM NBC Mob Doctor, Parks and Recreation, 9PM FOX 9:30PM NBC Revolution, Survivor: Philippines, Rock Center with Brian 10PM NBC 8PM CBS Williams, 10PM NBC Daniel Craig hosts 23 24 25 26 27 28 SNL with musical guest Muse, The 64th Dancing with the NCIS, 8PM CBS The Middle, 8PM ABC Last Resort, CSI: NY, 11:35PM NBC Annual Stars: All-Stars, Animal Practice, 8PM ABC 8PM CBS Primetime 8PM ABC New Girl, 8PM NBC Emmy 8PM FOX The Big Bang Theory, Kitchen Awards, How I Met Your Guys with Kids, 8PM CBS Mother, 8PM CBS Ben and Kate, 8:30PM NBC Nightmares, 8PM ABC 8PM FOX 8:30PM FOX Criminal Minds, 9PM CBS Two and a Half Men, Partners, 8:30PM CBS 8:30PM CBS NCIS: LA, 8PM CBS Law & Order: SVU, Fringe, 8PM NBC Grey’s Anatomy, 9PM