To Have Been a Student of Richard Feynman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman Louis de Broglie Norman Ramsey Willis Lamb Otto Stern Werner Heisenberg Walther Gerlach Ernest Rutherford Satyendranath Bose Max Born Erwin Schrödinger Eugene Wigner Arnold Sommerfeld Julian Schwinger David Bohm Enrico Fermi Albert Einstein Where discovery meets practice Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology IQ ST in Baden-Württemberg . Introduction “But I do not wish to be forced into abandoning strict These two quotes by Albert Einstein not only express his well more securely, develop new types of computer or construct highly causality without having defended it quite differently known aversion to quantum theory, they also come from two quite accurate measuring equipment. than I have so far. The idea that an electron exposed to a different periods of his life. The first is from a letter dated 19 April Thus quantum theory extends beyond the field of physics into other 1924 to Max Born regarding the latter’s statistical interpretation of areas, e.g. mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and even biology. beam freely chooses the moment and direction in which quantum mechanics. The second is from Einstein’s last lecture as Let us look at a few examples which illustrate this. The field of crypt it wants to move is unbearable to me. If that is the case, part of a series of classes by the American physicist John Archibald ography uses number theory, which constitutes a subdiscipline of then I would rather be a cobbler or a casino employee Wheeler in 1954 at Princeton. pure mathematics. Producing a quantum computer with new types than a physicist.” The realization that, in the quantum world, objects only exist when of gates on the basis of the superposition principle from quantum they are measured – and this is what is behind the moon/mouse mechanics requires the involvement of engineering. -

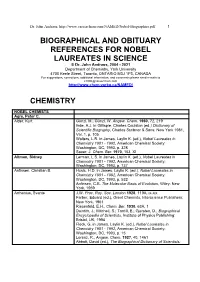

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

11/03/11 110311 Pisp.Doc Physics in the Interest of Society 1

1 _11/03/11_ 110311 PISp.doc Physics in the Interest of Society Physics in the Interest of Society Richard L. Garwin IBM Fellow Emeritus IBM, Thomas J. Watson Research Center Yorktown Heights, NY 10598 www.fas.org/RLG/ www.garwin.us [email protected] Inaugural Lecture of the Series Physics in the Interest of Society Massachusetts Institute of Technology November 3, 2011 2 _11/03/11_ 110311 PISp.doc Physics in the Interest of Society In preparing for this lecture I was pleased to reflect on outstanding role models over the decades. But I felt like the centipede that had no difficulty in walking until it began to think which leg to put first. Some of these things are easier to do than they are to describe, much less to analyze. Moreover, a lecture in 2011 is totally different from one of 1990, for instance, because of the instant availability of the Web where you can check or supplement anything I say. It really comes down to the comment of one of Elizabeth Taylor later spouses-to-be, when asked whether he was looking forward to his wedding, and replied, “I know what to do, but can I make it interesting?” I’ll just say first that I think almost all Physics is in the interest of society, but I take the term here to mean advising and consulting, rather than university, national lab, or contractor research. I received my B.S. in physics from what is now Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland in 1947 and went to Chicago with my new wife for graduate study in Physics. -

![I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8589/i-i-rabi-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-tue-apr-428589.webp)

I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr

I. I. Rabi Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1992 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998009 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89076467 Prepared by Joseph Sullivan with the assistance of Kathleen A. Kelly and John R. Monagle Collection Summary Title: I. I. Rabi Papers Span Dates: 1899-1989 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1968) ID No.: MSS76467 Creator: Rabi, I. I. (Isador Isaac), 1898- Extent: 41,500 items ; 105 cartons plus 1 oversize plus 4 classified ; 42 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Physicist and educator. The collection documents Rabi's research in physics, particularly in the fields of radar and nuclear energy, leading to the development of lasers, atomic clocks, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and to his 1944 Nobel Prize in physics; his work as a consultant to the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory and as an advisor on science policy to the United States government, the United Nations, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization during and after World War II; and his studies, research, and professorships in physics chiefly at Columbia University and also at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. -

Richard P. Feynman Author

Title: The Making of a Genius: Richard P. Feynman Author: Christian Forstner Ernst-Haeckel-Haus Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Berggasse 7 D-07743 Jena Germany Fax: +49 3641 949 502 Email: [email protected] Abstract: In 1965 the Nobel Foundation honored Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics and the consequences for the physics of elementary particles. In contrast to both of his colleagues only Richard Feynman appeared as a genius before the public. In his autobiographies he managed to connect his behavior, which contradicted several social and scientific norms, with the American myth of the “practical man”. This connection led to the image of a common American with extraordinary scientific abilities and contributed extensively to enhance the image of Feynman as genius in the public opinion. Is this image resulting from Feynman’s autobiographies in accordance with historical facts? This question is the starting point for a deeper historical analysis that tries to put Feynman and his actions back into historical context. The image of a “genius” appears then as a construct resulting from the public reception of brilliant scientific research. Introduction Richard Feynman is “half genius and half buffoon”, his colleague Freeman Dyson wrote in a letter to his parents in 1947 shortly after having met Feynman for the first time.1 It was precisely this combination of outstanding scientist of great talent and seeming clown that was conducive to allowing Feynman to appear as a genius amongst the American public. Between Feynman’s image as a genius, which was created significantly through the representation of Feynman in his autobiographical writings, and the historical perspective on his earlier career as a young aspiring physicist, a discrepancy exists that has not been observed in prior biographical literature. -

THE MEETING Meridel Rubenstein 1995

THE MEETING Meridel Rubenstein 1995 Palladium prints, steel, single-channel video Video assistance by Steina Video run time 4:00 minutes Tia Collection The Meeting consists of twenty portraits of people from San Ildefonso Pueblo and Manhattan Project physicists—who met at the home of Edith Warner during the making of the first atomic bomb—and twenty photographs of carefully selected objects of significance to each group. In this grouping are people from San Ildefonso Pueblo and the objects they selected from the collections of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture to represent their culture. 1A ROSE HUGHES 2A TALL-NECKED JAR 3A BLUE CORN 4A SLEIGH BELLS 5A FLORENCE NARANJO Rose Hughes holding a photograph of WITH AVANYU One of the most accomplished and (Museum of Indian Arts and Culture) Married to Louis Naranjo; her father, Tony Peña, who organized (plumed serpent) made by Julian and recognized of the San Ildefonso Sleigh bells are commonly used in granddaughter of Ignacio and Susana the building of Edith Warner’s second Maria Martinez, ca. 1930 (Museum of potters. Like many women from the ceremonial dances to attract rain. Aguilar; daughter of Joe Aguilar, who house. Hughes worked at Edith Indian Arts and Culture) Edith Warner pueblos, she worked as a maid for the Tilano Montoya returned with bells like helped Edith Warner remodel the Warner’s with Florence Naranjo one was shown a pot like this one in 1922 Oppenheimers. these from Europe, where he went on tearoom. Edith called her Florencita. summer. She recalls that Edith once on her first visit to San Ildefonso, in the tour with a group of Pueblo dancers. -

More Eugene Wigner Stories; Response to a Feynman Claim (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on August 29, 2016)

More Eugene Wigner stories; Response to a Feynman claim (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column on August 29, 2016) Carolyn Krause has collected a couple more stories about Eugene Wigner, plus a response by Y- 12 to allegations by Richard Feynman in a book that included a story on his experience at Y-12 during World War II. … Mary Ann Davidson, widow of Jack Davidson, a longtime member of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Instrumentation and Controls Division, told me about Jack’s encounter with Wigner one day. Once Eugene Wigner had trouble opening his briefcase while visiting ORNL. He was referred to Jack Davidson in the old Instrumentation and Controls Division. Jack managed to open it for him. As was his custom, Wigner asked Jack about his research. Jack, who later won an R&D-100 award, said he was building a camera that will imitate a fly’s eye; in other words, it will capture light coming from a variety of directions. The topic of television and TV cameras came up. Wigner said he wondered how TV works. So Davidson explained the concept to him. Charles Jones told me this story about Eugene Wigner when he visited ORNL in the 1980s. Jones, who was technical director of the Holifield Heavy Ion Research Facility, said he invited Wigner to accompany him to the top of the HHIRF tower, and Wigner happily accepted the offer. At the top Wigner looked down at all the ORNL buildings, most of which had been constructed after he was the lab’s research director in 1946-47. -

An Investigation of the American Atomic Narrative Through News and Magazine Articles, Official Government Statements, Critiques, Essays and Works of Non/Fiction

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository Atomic Evangelists: An Investigation of the American Atomic Narrative Through News and Magazine Articles, Official Government Statements, Critiques, Essays and Works of Non/Fiction 髙田, とも子 https://doi.org/10.15017/4059961 出版情報:九州大学, 2019, 博士(文学), 課程博士 バージョン: 権利関係: Doctoral Dissertation Atomic Evangelists: An Investigation of the American Atomic Narrative Through News and Magazine Articles, Official Government Statements, Critiques, Essays and Works of Non-Fiction Tomoko Takada January 2020 Graduate School of Humanities Kyushu University Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Professor Takano, who has always provided me with unwavering support and guidance since the day I entered Kyushu University’s graduate program. In retrospect, I could not have chosen my research topic had it not been for his constructive advice. His insightful suggestions helped me understand that literature, or in a broader sense, humanities, can go far beyond the human imagination. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the members of Genbaku Bungaku Kenkyukai, especially Kyoko Matsunaga, Michael Gorman, Takayuki Kawaguchi, Tomoko Ichitani and Shoko Itoh for generously sharing their extensive knowledge and giving me the most creative and practical comments on my research. Ever since I joined this group in 2011, their advice never failed to give me a sense of “epiphany”. As for the grants that supported my research for writing this dissertation, I am extremely grateful to Kyushu University Graduate School of Humanities, JSPS, The America-Japan Society and the US Embassy in Japan for offering me the invaluable opportunity to conduct my research in the United States. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

Nuclear Weapons and Nuclear War. Papers Based on a Symposium Of

. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 233 910 SE 043 147 A AUTHOR Mo'irison, Philip; And Others TITLE Nuclear Weapcins and'Nuclear War. Papers Based on a.' symposium of the Forum on Physics and Society of the American Physical Society, (ashington, D.C., April 1982.). INSTITUTION Americ'ap Association of Physics Teachers, Washington, 'D.C. 0 PUB DATE 83 NOTE 44. L AVAILABLE FROM American AssoCiatiOn of Physics Teachers, Graduate Phygics Bldg., SUNY, Stony Btook, NY,11794._(Nuclear Weapons $2.00 U.S., prepaid; Nuclear Energy $2.50 U.S./$3.00 outside U.S.). PUB TYPE Reports - General (140) Speeches/Conference Papers (150.) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Armed Forces; *Disarmament; *Intetnational Relations; National Defense; Nuclear Technology; *Nuclear Warfare; Treaties; *World Problems IDENTIFIERS *Nuclear Weapons; *USSR ABSTRACT Three papers on nuclear weapons and nuclear war, baged on talks 'given by distinguihed physicists during an American Physical Society-sponsored symposium,,-are provided in this booklet. They include "Caught Between Asymptotes" (Philip Morrison), "We are not Inferior to the Soviets" (Hans A. Bethe), and "MAD vs. NUTS" (Wolfgang K. H.. Panofsky).'Areas addressed in the first paper (whose title is based on a metaphOr offered by, John von Neumann) include the threat of nuclear war, WorldWar III. versus World War II, and .others. The major point of the second paper is that United States strategic nuclear forces are not infeiior to those of the Soviets., Areas addressed include accuracy/vulnerability, new weapons, madness of .nuclear war, SALT I and II, proposed nuclear weapons freeze, and possible U.S initiatives'. -

Cornell Gets a New Chair

PEOPLE APPOINTMENTS & AWARDS Cornell gets a new chair Two prominent accelerator physicists and Cornell alumni, Helen T Edwards and her husband, Donald A Edwards, have endowed a chair in accelerator physics at Cornell.The chair is named after Boyce D McDaniel, pro fessor emeritus at Cornell. The first holder of the new chair is David L Rubin, professor of physics and director of accelerator physics at Cornell.The donors David Rubin is the first incumbent of the new Boyce McDaniel Chair of Physics at Cornell, asked that the new professorship should be endowed by Helen and Donald Edwards. The chair is named after Boyce D McDaniel. Left awarded to a Cornell faculty member whose to right: Boyce McDaniel, Donald Edwards, David Rubin, Helen Edwards and Maury Tigner, discipline is particle-beam physics and who director of Cornell's Laboratory of Nuclear Studies. would teach both graduate and undergradu ate students in addition to doing research. McDaniel, a previous director of nuclear ingthe commissioning of the Main Ring at Helen Edwards is a 1957 graduate of science at Cornell, was Helen Edwards' thesis Fermilab and providing advice for numerous Cornell, where she also earned her PhD in adviser. Initially a graduate student at Cornell, accelerator projects throughout the US, in 1966. She works at Fermilab and at DESY in he left during the Second World War to join the addition to his notable contributions to the Germany. She played a prominent role in the Manhattan Project and returned to complete accelerator and elementary particle physics construction of Fermilab'sTevatron and has his PhD, joining the faculty in 1946. -

Vol25-Issue6.Pdf

Vancouver Accelerator Conference Michael Craddock, Chairman of the Conference, and Accelerator Research Division Head at the TRIUMF Laboratory gives the opening address at the 1985 Particle Accelerator Conference in Vancouver. He and his colleagues are to be congratulated on the very smooth organization of such a large gathering. Anyone who contends that particle physics is conducted in an ivory tower, not contributing to other fields of science or to humanity at large, should have attended the 1985 Particle Accelerator Confer ence in Vancouver. Over a thou sand participants contributed 781 papers and only a fraction were actually related to accelerators for nigh energy physics. The majority of present developments are in the service of other fields of science, for alternative power sources, for medicine, for industrial applica tions, etc. Nevertheless, it is the spur of high energy physics that has dri ven accelerator technology along. As Burt Richter pointed out, in some fifty years since the first Cockcroft-Walton accelerators were built, accelerator physicists have increased peak machine energies by a factor of a million and have reduced the cost per GeV by a factor of over ten thou larly the machine diameter. ing problems, good cooling and sand. Conference Chairman Mike Though there are variants - with straightforward \)raddock rejoiced in his opening such as two-in-one (both beam ap manufacturing processes. Address that the contributions of ertures in a single yoke) or one-in- Paul Reardon reported on the al the accelerator community had one designs - there are essentially ternative high field type for which been so significantly recognized at two basic magnet types now un the initially separate proposals of the end of the last year with the der consideration.