Experimental Film and Video in Lebanon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 7 (2021), 2845-2852 Research Article Undermining Colonial Space in Cinematic Discourse

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 7 (2021), 2845-2852 Research Article Undermining Colonial Space In Cinematic Discourse Dr. Ammar Ibrahim Mohammed Al-Yasri Television Arts specialization Ministry of Education / General Directorate of Holy Karbala Education [email protected] Article History: Received: 11 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 16 April 2021 Abstract: There is no doubt that artistic races are the fertile factor in philosophy in all of its perceptions, so cinematic discourse witnessed from its early beginnings a relationship to philosophical thought in all of its proposals, and post-colonial philosophy used cinematic discourse as a weapon that undermined (colonial) discourse, for example cinema (Novo) ) And black cinema, Therefore, the title of the research came from the above introduction under the title (undermining the colonial space in cinematic discourse) and from it the researcher put the problem of his research tagged (What are the methods for undermining the colonial space in cinematic discourse?) And also the first chapter included the research goal and its importance and limitations, while the second chapter witnessed the theoretical framework It included two topics, the first was under the title (post-colonialism .. the conflict of the center and the margin) and the second was under the title (post-colonialism between cinematic types and aspects of the visual form) and the chapter concludes with a set of indicators, while the third chapter included research procedures, methodology, society, sample and analysis of samples, While the fourth chapter included the results and conclusions, and from the results obtained, the research sample witnessed the use of undermining the (colonial) act, which was embodied in the face of violence with violence and violence with culture, to end the research with the sources. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 58 ANNÉE – Nº 17830 – 1,20 ¤ – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE --- VENDREDI 24 MAI 2002 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI 0123 A Moscou, DES LIVRES L’école de Luc Ferry Bush et Poutine Roberto Calasso Grecs à Montpellier Illettrisme, enseignement professionnel, autorité : les trois priorités du ministre de l’éducation consacrent un Le cinéma et l’écrit LE NOUVEAU ministre de l’édu- f rapprochement cation nationale, Luc Ferry, expose Un entretien avec INCENDIE dans un entretien au Monde ses le nouveau ministre « historique » trois priorités : la lutte contre l’illet- de la jeunesse L’ambassade d’Israël trisme, la valorisation de l’enseigne- ment professionnel et la consolida- et de l’éducation LORS de sa première visite officiel- à Paris détruite dans la tion de l’autorité des professeurs, le en Russie, le président américain nuit. Selon la police, le qu’il lie à la sécurité. Pour l’illettris- George W. Bush signera avec Vladi- me, Luc Ferry reproche à ses prédé- f « Il faut revaloriser mir Poutine, vendredi 24 mai au feu était accidentel p. 11 cesseurs de n’avoir « rien fait Kremlin, un traité de désarmement depuis dix ans ». Il insiste sur le res- la pédagogie nucléaire qualifié d’« historique » et MAFIA pect des horaires de lecture et du travail » à l’école visant à « mettre fin à la guerre froi- d’écriture, ainsi que sur la prise en de ». Les deux pays s’engagent à Dix ans après la mort charge des jeunes en difficulté. réduire leurs arsenaux stratégiques à L’enseignement professionnel doit f Médecins : un niveau maximal de 2 200 ogives à du juge Falcone p. -

1 GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY VISITING FILM SERIES April 29

GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY VISITING FILM SERIES April 29, 2020 I am pleased to be here to talk about my role as Deputy Director of the Washington, DC International Film Festival, more popularly known as Filmfest DC, and as Director of the Arabian Sights Film Festival. I would like to start with a couple of statistics: We all know that Hollywood films dominate the world’s movie theaters, but there are thousands of other movies made around the globe that most of us are totally unaware of or marginally familiar with. India is the largest film producing nation in the world, whose films we label “Bollywood”. India produces around 1,500 to 2,000 films every year in more than 20 languages. Their primary audience is the poor who want to escape into this imaginary world of pretty people, music and dancing. Amitabh Bachchan is widely regarded as the most famous actor in the world, and one of the greatest and most influential actors in world cinema as well as Indian cinema. He has starred in at least 190 movies. He is a producer, television host, and former politician. He is also the host of India’s Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. Nigeria is the next largest film producing country and is also known as “Nollywood”, producing almost 1000 films per year. That’s almost 20 films per week. The average Nollywood movie is produced in a span of 7-10 days on a budget of less than $20,000. Next comes Hollywood. Last year, 786 films were released in U.S. -

Programme-2006.Pdf

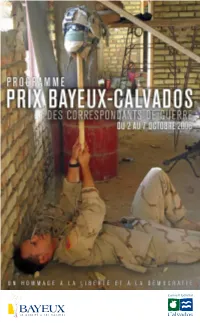

Programme PRIX BAYEUX-CALVADOS Édition 2006 DES CORRESPONDANTS DE GUERRE 2006 Lundi 2 octobre P Prix des lycéens J’ai le plaisir de vous Basse-Normandie présenter la 13e édition Mardi 3 octobre du Prix Bayeux-Calvados P Cinéma pour les collégiens des Correspondants de Guerre. Mercredi 4 octobre P Ouverture des expositions Fenêtre ouverte sur le monde, sur ses conflits, sur les difficultés du métier d’informer, Jeudi 5 octobre ce rendez-vous majeur des médias internationaux et du public rappelle, d’année en année, notre attachement à la démocratie et à son expression essentielle : P Soirée grands reporters : la liberté de la presse. Liban, nouveau carrefour Les débats, les projections et les expositions proposés tout au long de cette semaine de tous les dangers offrent au public et notamment aux jeunes l’éclairage de grands reporters et le décryptage d’une actualité internationale complexe et souvent dramatique. Vendredi 6 octobre Cette année plus que jamais, Bayeux témoignera de son engagement en inaugurant P Réunion du jury avec Reporters sans frontières, le « Mémorial des Reporters », site unique en Europe, international dédié aux journalistes du monde entier disparus dans l’exercice de leur profession pour nous délivrer une information libre, intègre et sincère. P Soirée hommage et projection en avant-première J’invite chacune et chacun d’entre vous à venir nous rejoindre du 2 au 7 octobre du film “ L’Étoile du Soldat ” à Bayeux, pour partager cette formidable semaine d’information, d’échange, d’hommage et d’émotion. de Christophe De Ponfilly PATRICK GOMONT Samedi 7 octobre Maire de Bayeux P Réunion du jury international et du jury public P Inauguration du Mémorial des reporters avec Reporters sans frontières P Salon du livre VOUS Le Prix du public, catégorie photo, aura lieu le samedi 7 octobre, de 10 h à 11 h, à la Halle aux Grains P SOUHAITEZ Table ronde sur la sécurité de Bayeux. -

Ar Risalah) Among the Moroccan Diaspora

. Volume 9, Issue 1 May 2012 Connecting Islam and film culture: The reception of The Message (Ar Risalah) among the Moroccan diaspora Kevin Smets University of Antwerp, Belgium. Summary This article reviews the complex relationship between religion and film-viewing among the Moroccan diaspora in Antwerp (Belgium), an ethnically and linguistically diverse group that is largely Muslim. A media ethnographic study of film culture, including in-depth interviews, a group interview and elaborate fieldwork, indicates that film preferences and consumption vary greatly along socio-demographic and linguistic lines. One particular religious film, however, holds a cult status, Ar Risalah (The Message), a 1976 historical epic produced by Mustapha Akkad that deals with the life of the Prophet Muhammad. The film’s local distribution is discussed, as well as its reception among the Moroccan diaspora. By identifying three positions towards Islam, different modes of reception were found, ranging from a distant and objective to a transparent and subjective mode. It was found that the film supports inter-generational religious instruction, in the context of families and mosques. Moreover, a specific inspirational message is drawn from the film by those who are in search of a well-defined space for Islam in their own lives. Key words: Film and diaspora, media ethnography, Moroccan diaspora, Islam, Ar Risalah, The Message, Mustapha Akkad, religion and media Introduction The media use of diasporic communities has received significant attention from a variety of scholarly fields, uncovering the complex roles that transnational media play in the construction of diasporic connectedness (both ‘internal’ among diasporic communities as well as with countries of origin, whether or not ‘imagined’), the negotiation of identity and the enunciation of socio-cultural belongings. -

MMF-2017 Katalog.Pdf

2 Welcome to MAFF Market Forum MAFF Market Forum 2 3 4 e city of Malmö Welcome to Malmö 5 7 Meet the experts Forum 40 41 Schedule Market Screenings 54 64 Critics Without Borders Nordic countries – Egypt 2017 Case Study / Beauty And e Dogs 70 CONTENT 1 General Manager Mouhamad Keblawi Photographer: Yazan Saad I WANT TO WISH YOU all a warm welcome to MAFF Market Forum 2017. We are both excited and proud to present our third edition of this unique and propitious industry platform. MAFF Market Forum was launched with the ambition to bring the two worlds together, intertwining them with a tailored program created to build partnerships in an intimate environment. We bring together producers, funders, distributors and lm professionals in order to foster a cultural exchange and expand the production landscape. MAFF Market Forum was sprung out of the same ambition as the festival itself; to promote the Arab lm industry, create a gender and cultural diversity in the lm industry, and of course - to ensure all stories get a chance to be heard and seen. Even before the implementation of the rst edition of MAFF Market Forum, we realized that the initiative would have a major impact. Said and done - today, after only two years, several Nordic-Arabic lm collaborations have been implemented and initiated through our platform. And when we say our platform, we include an incredibly important part of the success; the participants. We are beyond thrilled to every year welcome lm professionals from all over the world. is year is no exception, and some of the most signicant and inuential institutes and organizations from both the Nordic countries and the Arab world are attending. -

Film Genres, the Muslim Social, and Discourses of Identity C. 1935–1945

Article BioScope Film Genres, the Muslim Social, and 6(1) 27–43 © 2015 Screen South Asia Trust Discourses of Identity c. 1935–1945 SAGE Publications sagepub.in/home.nav DOI: 10.1177/0974927615586930 http://bioscope.sagepub.com Ravi S. Vasudevan1 Abstract This article explores the phenomenon of the Muslim social film and “Islamicate” cinema of pre-Partition India to suggest a significant background to cinema’s function in the emergence of new states. In particu- lar, it seeks to provide an account of how discussions of genre and generic difference framed issues of audience and identity in the studio period of Indian film, broadly between the mid-1930s and mid-1940s. Rather than focus too narrowly on identity discourses in the cinema, I try to move among amorphous and dispersed senses of audience, more calibrated understandings related to a trade discourse of who films would appeal to, and finally, an agenda of social representation and audience address that sought to develop in step with a secular nationalist imagining of the Muslim community and its transformation. Keywords Muslim social, Mehboob, K.A. Abbas, Islamicate, oriental, Lahore This article explores the phenomenon of the Muslim social film and “Islamicate” cinema of pre-Partition India to suggest a significant background to cinema’s function in the emergence of new states. In particu- lar, it seeks to provide an account of how discussions of genre and generic difference framed issues of audience and identity in the studio period of Indian film, broadly between the mid-1930s and mid-1940s. Rather than focus too narrowly on identity discourses in the cinema, I try to move among amorphous and dispersed senses of audience, more calibrated understandings related to a trade discourse of who films would appeal to, and finally, an agenda of social representation and audience address that sought to develop in step with a secular nationalist imagining of the Muslim community and its transformation. -

Western Europe

Western Europe Great Britain National Affairs A. HE DOMINANT POLITICAL EVENT of 1987 was the Conservative vic- tory in the general election in June. Margaret Thatcher entered an unprecedented third term as prime minister with a total of 375 seats, giving her a slightly reduced majority over the previous term. Labor won 229 seats, a small increase; and the Liberal-Social Democratic Alliance, 22, a slight drop. While the results clearly confirmed the success of the "Thatcher revolution" among the enlarged middle class, they also revealed the ongoing divisions in British society, geographic and economic. The Conservatives scored heavily in London, southern England, and the Midlands, while Labor was strong in economically depressed areas in Wales, Scot- land, and the north. In the election aftermath, the two parties constituting the Alliance, i.e., the Liberals and the Social Democrats, decided to go their separate ways, amid mutual recriminations, although an attempt was made by part of the Social Democrats to merge with the Liberals. On the Labor side, its third successive defeat gave impetus to a major reconsideration of traditional party policies. The Tory victory reflected satisfaction with a generally improved economy. In March the chancellor of the exchequer was able to reduce income taxes without imposing any further taxes on gasoline, tobacco, or liquor. Unemployment, which had reached 3.25 million in February, declined by the end of the year to 2.8 million, less than 10 percent of the working population. During the whole year there were fewer than 1,000 separate strikes—for only the second time since 1940. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Previously Published Works

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Previously Published Works Title “Of Marabouts, Acrobats, and Auteurs: Framing the Global Popular in Moumen Smihi’s World Cinema.” Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1r86d1c5 Author Limbrick, Peter Publication Date 2021 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California FINAL ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT, FORTHCOMING IN CULTURAL CRITIQUE, 2021 “Of Marabouts, Acrobats, and Auteurs: Framing the Global Popular in Moumen Smihi’s World Cinema.” Peter Limbrick, Film and Digital Media, University of California, Santa Cruz One of the critical commonplaces in the study of Arab cinemas is the idea that we can distinguish between Egyptian cinema, a dominant popular and industrial cinema akin to Hollywood, and smaller national or regional cinemas (Palestinian, Tunisian, Algerian, Moroccan) which are typically discussed as auteur or art cinemas. While historically defensible, in that Egypt preceded these others in having its own studios and industry, such an assessment nonetheless tends to foreclose on the possibilities for those films inhabiting the “non-Egyptian” model ever be accorded the status of popular cinema. Moreover, where local distribution and exhibition for North African films has been historically partial or non-existent (due to commercial decisions that have historically favored Egyptian, Indian, and Euro-American productions), it has been difficult for many directors in countries like Morocco to avoid the charge that their films—which are often more visible in European festivals than at home—are made for other markets or audiences. Whether in sympathy with the idea of distinctive local or national cinemas and resistance to cultural hegemony, or in suspicion of the politics of international funding and coproduction, many critical treatments of non-Egyptian Arab films make of the popular an evaluative term that signifies local authenticity and a resistance towards European art cinema tendencies and that privileges commercial success over experimentation. -

Prix Bayeux-Calvados

PRIX BAYEUX-CALVADOS PRIX BAYEUX-CALVADOS DES CORRESPONDANTS DE GUERRE DES CORRESPONDANTS DE GUERRE Un hommage à la liberté et à la démocratie Plan de Bayeux Karim SAHIB/AFP - Trophée photo 2004 photo Trophée - SAHIB/AFP Karim la Ville de Bayeux et le conseil général du Calvados remercient leurs partenaires Du 3 au 8 octobre 2005 PROGRAMME Pour toute information sur l’événement : mairie de Bayeux 08/2005 DBL Communication - Tél. 02 31 15 Tél. 21 08/2005 d’images 15 DBL – - Communication Photo - Maquette : de L’Ivre couverture Éditorial « Se vouloir libre, c’est d’abord vouloir les PRIX BAYEUX-CALVADOS autres libres » DES CORRESPONDANTS DE GUERRE C’est avec cette citation de Simone de Beauvoir que s’ouvrira prochainement à Bayeux l’espace dédié aux journalistes tués dans l’exercice de leur métier depuis 1944. Ce projet, réalisé Un hommage à la liberté et à la démocratie avec Reporters sans frontières, se concrétise alors que 2004 a été l’une des années les plus meurtrières pour la profession de journaliste. A travers ce pôle unique en France, Bayeux affirme son attachement à défendre la liberté de la presse. Du 3 au 8 octobre 2005 u fil des éditions, le Prix Bayeux-Calvados des correspondants de guerre, A« un hommage à la liberté et la démocratie », a su s’imposer comme un Lundi 3 octobre événement majeur auprès des médias internationaux. Depuis plusieurs années, • Prix des lycéens grâce particulièrement au soutien du conseil général du Calvados et de nos partenaires, nous nous sommes attachés à ouvrir cet événement au public à travers une programmation élargie : soirées-débats, expositions, prix du public, Mardi 4 octobre prix des lycéens, salon du livre.. -

Wipo Magazine

APRIL 2018 No. 2 Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Gender equality in From brewing to biologics: Story – an interview with African agriculture: Biocon’s Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw Alexandra Dean an innovation imperative transforms global health p. 8 p. 34 p. 27 Powering change: Women in innovation and creativity World Intellectual Property Day 2018 April 26 Powering change: Women in innovation and creativity World Intellectual Property Day 2018 April 26 Every day women come up with game-changing inven- world. Their “can do” attitude is an inspiration to us all. tions and life-enhancing creations that transform lives And their remarkable achievements are an invaluable and advance human understanding from astrophysics legacy for young girls today with aspirations to become to nanotechnology and from medicine to artificial in- the inventors and creators of tomorrow. telligence and robotics. This special focus issue of the WIPO Magazine explores And in the creative sphere, whether in the movies, anima- why it is important to encourage women in innovation tion, music, fashion, design, sculpture, dance, literature, and creativity and presents the views and experiences art and more, women are re-imagining culture, testing of just a few of the many remarkable women who are the limits of artistry and creative expression, drawing us powering change in our world every day. into new worlds of experience and understanding. For more on World Intellectual Property Day, join us on The important and inspiring contributions of countless Twitter (#worldipday) and Facebook (www.facebook. women around the globe are powering change in our com/worldipday). WIPO MAGAZINE April 2018 / No. -

Dubbing Into Arabic: a Trojan Horse at the Gates?

DUBBING INTO ARABIC: A TROJAN HORSE AT THE GATES? By Ramez Maluf Summary: This paper examines the reasons why the dubbing of American film and television programs, common throughout much of the world, remains non-existent in the Arab world. Despite a considerable surge in television stations and much need for quality programs, dubbing into Arabic is limited to a few Latin American soaps, children’s cartoons and, more recently, Iranian films. Will an increase in dubbed Western programs reflect a greater encroachment of a global culture in the Arab world? Dubbing, the replacing of the original dialogue or soundtrack by another, either in a different language or voice, dates back to the early days of film. Following the success of the talkies at the close of the 1920s, silent movies became obsolete within a matter of a few years, prompting the film industry to look at their actors in an entirely new way. How they sounded was now as important as how they looked and acted. With audiences able to enjoy dialogue, actors’ voices and related sounds became an integral consideration of film production. When the articulation, intonation, accent, or dialect of the stars of the silent silver screen were inappropriate for the new movies, studios resorted to dubbing over the dialogue, by adjusting the mouth movements of the original actors in the film to the voice of other actors. Thus, the practice of lip-synching was introduced. Later, studios would entirely replace stars of the silent screen whose voices were inappropriate for the talkies (Parkinson 85-86). Outside the United States, in Latin America and Europe, where Hollywood productions started to make serious inroads as early as the late 1910s, the fact of sound and dialogue forced distributors to consider ways to reach out to their non-English speaking audiences.