Changes in the Vaginal Microbiota Across a Gradient of Urbanization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio In

microorganisms Review The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease Spase Stojanov 1,2, Aleš Berlec 1,2 and Borut Štrukelj 1,2,* 1 Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Biotechnology, Jožef Stefan Institute, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia * Correspondence: borut.strukelj@ffa.uni-lj.si Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 31 October 2020; Published: 1 November 2020 Abstract: The two most important bacterial phyla in the gastrointestinal tract, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, have gained much attention in recent years. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio is widely accepted to have an important influence in maintaining normal intestinal homeostasis. Increased or decreased F/B ratio is regarded as dysbiosis, whereby the former is usually observed with obesity, and the latter with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Probiotics as live microorganisms can confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. There is considerable evidence of their nutritional and immunosuppressive properties including reports that elucidate the association of probiotics with the F/B ratio, obesity, and IBD. Orally administered probiotics can contribute to the restoration of dysbiotic microbiota and to the prevention of obesity or IBD. However, as the effects of different probiotics on the F/B ratio differ, selecting the appropriate species or mixture is crucial. The most commonly tested probiotics for modifying the F/B ratio and treating obesity and IBD are from the genus Lactobacillus. In this paper, we review the effects of probiotics on the F/B ratio that lead to weight loss or immunosuppression. -

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Genomics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ygeno Whole-genome comparison clarifies close phylogenetic relationships between the phyla Dictyoglomi and Thermotogae Hiromi Nishida a,⁎, Teruhiko Beppu b, Kenji Ueda b a Agricultural Bioinformatics Research Unit, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Tokyo, 1-1-1 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan b Life Science Research Center, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, Fujisawa, Japan article info abstract Article history: The anaerobic thermophilic bacterial genus Dictyoglomus is characterized by the ability to produce useful Received 2 June 2011 enzymes such as amylase, mannanase, and xylanase. Despite the significance, the phylogenetic position of Accepted 1 August 2011 Dictyoglomus has not yet been clarified, since it exhibits ambiguous phylogenetic positions in a single gene Available online 7 August 2011 sequence comparison-based analysis. The number of substitutions at the diverging point of Dictyoglomus is insufficient to show the relationships in a single gene comparison-based analysis. Hence, we studied its Keywords: evolutionary trait based on whole-genome comparison. Both gene content and orthologous protein sequence Whole-genome comparison Dictyoglomus comparisons indicated that Dictyoglomus is most closely related to the phylum Thermotogae and it forms a Bacterial systematics monophyletic group with Coprothermobacter proteolyticus (a constituent of the phylum Firmicutes) and Coprothermobacter proteolyticus Thermotogae. Our findings indicate that C. proteolyticus does not belong to the phylum Firmicutes and that the Thermotogae phylum Dictyoglomi is not closely related to either the phylum Firmicutes or Synergistetes but to the phylum Thermotogae. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. -

Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis David Johane Machate 1, Priscila Silva Figueiredo 2 , Gabriela Marcelino 2 , Rita de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães 2,*, Priscila Aiko Hiane 2 , Danielle Bogo 2, Verônica Assalin Zorgetto Pinheiro 2, Lincoln Carlos Silva de Oliveira 3 and Arnildo Pott 1 1 Graduate Program in Biotechnology and Biodiversity in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] (D.J.M.); [email protected] (A.P.) 2 Graduate Program in Health and Development in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; pri.fi[email protected] (P.S.F.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (P.A.H.); [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (V.A.Z.P.) 3 Chemistry Institute, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-67-3345-7416 Received: 9 March 2020; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 8 June 2020 Abstract: Long-term high-fat dietary intake plays a crucial role in the composition of gut microbiota in animal models and human subjects, which affect directly short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and host health. This review aims to highlight the interplay of fatty acid (FA) intake and gut microbiota composition and its interaction with hosts in health promotion and obesity prevention and its related metabolic dysbiosis. -

Table S4. Phylogenetic Distribution of Bacterial and Archaea Genomes in Groups A, B, C, D, and X

Table S4. Phylogenetic distribution of bacterial and archaea genomes in groups A, B, C, D, and X. Group A a: Total number of genomes in the taxon b: Number of group A genomes in the taxon c: Percentage of group A genomes in the taxon a b c cellular organisms 5007 2974 59.4 |__ Bacteria 4769 2935 61.5 | |__ Proteobacteria 1854 1570 84.7 | | |__ Gammaproteobacteria 711 631 88.7 | | | |__ Enterobacterales 112 97 86.6 | | | | |__ Enterobacteriaceae 41 32 78.0 | | | | | |__ unclassified Enterobacteriaceae 13 7 53.8 | | | | |__ Erwiniaceae 30 28 93.3 | | | | | |__ Erwinia 10 10 100.0 | | | | | |__ Buchnera 8 8 100.0 | | | | | | |__ Buchnera aphidicola 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pantoea 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Yersiniaceae 14 14 100.0 | | | | | |__ Serratia 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Morganellaceae 13 10 76.9 | | | | |__ Pectobacteriaceae 8 8 100.0 | | | |__ Alteromonadales 94 94 100.0 | | | | |__ Alteromonadaceae 34 34 100.0 | | | | | |__ Marinobacter 12 12 100.0 | | | | |__ Shewanellaceae 17 17 100.0 | | | | | |__ Shewanella 17 17 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonadaceae 16 16 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonas 15 15 100.0 | | | | |__ Idiomarinaceae 9 9 100.0 | | | | | |__ Idiomarina 9 9 100.0 | | | | |__ Colwelliaceae 6 6 100.0 | | | |__ Pseudomonadales 81 81 100.0 | | | | |__ Moraxellaceae 41 41 100.0 | | | | | |__ Acinetobacter 25 25 100.0 | | | | | |__ Psychrobacter 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Moraxella 6 6 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudomonadaceae 40 40 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudomonas 38 38 100.0 | | | |__ Oceanospirillales 73 72 98.6 | | | | |__ Oceanospirillaceae -

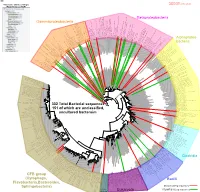

Bacteria Clostridia Bacilli Eukaryota CFB Group

AM935842.1.1361 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY283260.1.1552 Alcaligenes sp. PCNB−2 Class Betaproteobacteria AM934953.1.1374 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581593.1.1460 uncultured betaAM936569.1.1351 proteobacterium uncultured Class Betaproteobacteria Derxia sp. Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581621.1.1418 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ248272.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium soil uncultured DQ248272.1.1498 DQ248235.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium RS49 DQ248270.1.1496 uncultured soil bacterium DQ256489.1.1211 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax DQ256489.1.1211 AF523053.1.1486 uncultured Comamonadaceae bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY706442.1.1396 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY706442.1.1396 AJ536763.1.1422 uncultured bacterium CS000359.1.1530 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax CS000359.1.1530 AY168733.1.1411 uncultured bacterium AJ009470.1.1526 uncultured bacterium SJA−62 Class Betaproteobacteria Class SJA−62 bacterium uncultured AJ009470.1.1526 AY212561.1.1433 uncultured bacterium D16212.1.1457 Rhodoferax fermentans Class Betaproteobacteria Class fermentans Rhodoferax D16212.1.1457 AY957894.1.1546 uncultured bacterium AJ581620.1.1452 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria RS76 AY625146.1.1498 uncultured bacterium RS65 DQ316832.1.1269 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ404909.1.1513 uncultured bacterium uncultured DQ404909.1.1513 AB021341.1.1466 bacterium rM6 AJ487020.1.1500 uncultured bacterium uncultured AJ487020.1.1500 RS7 RS86RC AF364862.1.1425 bacterium BA128 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957931.1.1529 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957931.1.1529 CP000884.723807.725332 Delftia acidovorans SPH−1 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957923.1.1520 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957923.1.1520 RS18 AY957918.1.1527 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957918.1.1527 AY945883.1.1500 uncultured bacterium AF526940.1.1489 uncultured Ralstonia sp. -

Gut Microbiota Differs in Composition and Functionality Between Children

Diabetes Care Volume 41, November 2018 2385 Gut Microbiota Differs in Isabel Leiva-Gea,1 Lidia Sanchez-Alcoholado,´ 2 Composition and Functionality Beatriz Mart´ın-Tejedor,1 Daniel Castellano-Castillo,2,3 Between Children With Type 1 Isabel Moreno-Indias,2,3 Antonio Urda-Cardona,1 Diabetes and MODY2 and Healthy Francisco J. Tinahones,2,3 Jose´ Carlos Fernandez-Garc´ ´ıa,2,3 and Control Subjects: A Case-Control Mar´ıa Isabel Queipo-Ortuno~ 2,3 Study Diabetes Care 2018;41:2385–2395 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0253 OBJECTIVE Type 1 diabetes is associated with compositional differences in gut microbiota. To date, no microbiome studies have been performed in maturity-onset diabetes of the young 2 (MODY2), a monogenic cause of diabetes. Gut microbiota of type 1 diabetes, MODY2, and healthy control subjects was compared. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/COMPLICATIONS RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS This was a case-control study in 15 children with type 1 diabetes, 15 children with MODY2, and 13 healthy children. Metabolic control and potential factors mod- ifying gut microbiota were controlled. Microbiome composition was determined by 16S rRNA pyrosequencing. 1Pediatric Endocrinology, Hospital Materno- Infantil, Malaga,´ Spain RESULTS 2Clinical Management Unit of Endocrinology and Compared with healthy control subjects, type 1 diabetes was associated with a Nutrition, Laboratory of the Biomedical Research significantly lower microbiota diversity, a significantly higher relative abundance of Institute of Malaga,´ Virgen de la Victoria Uni- Bacteroides Ruminococcus Veillonella Blautia Streptococcus versityHospital,Universidad de Malaga,M´ alaga,´ , , , , and genera, and a Spain lower relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and 3Centro de Investigacion´ BiomedicaenRed(CIBER)´ Lachnospira. -

The Human Milk Microbiota Is Modulated by Maternal Diet

microorganisms Article The Human Milk Microbiota is Modulated by Maternal Diet Marina Padilha 1,2,*, Niels Banhos Danneskiold-Samsøe 3, Asker Brejnrod 3, Christian Hoffmann 1,2, Vanessa Pereira Cabral 1,4, Julia de Melo Iaucci 1, Cristiane Hermes Sales 4 , Regina Mara Fisberg 4 , Ramon Vitor Cortez 1, Susanne Brix 5 , Carla Romano Taddei 1,6, Karsten Kristiansen 3 and Susana Marta Isay Saad 1,2,* 1 School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo 05508-000, SP, Brazil; c.hoff[email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (V.P.C.); [email protected] (J.d.M.I.); [email protected] (R.V.C.); [email protected] (C.R.T.) 2 Food Research Center (FoRC), University of São Paulo, São Paulo 05508-000, SP, Brazil 3 Laboratory of Genomics and Molecular Biomedicine, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] (N.B.D.-S.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (K.K.) 4 School of Public Health, University of São Paulo, São Paulo 01246-904, SP, Brazil; [email protected] (C.H.S.); regina.fi[email protected] (R.M.F.) 5 Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark; [email protected] 6 School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities, University of São Paulo, São Paulo 03828-000, SP, Brazil * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (S.M.I.S.) Received: 17 September 2019; Accepted: 24 October 2019; Published: 29 October 2019 Abstract: Human milk microorganisms contribute not only to the healthy development of the immune system in infants, but also in shaping the gut microbiota. -

Prevotella Biva Poster.Pptx

Novel Infection Status Post Electrocution Requiring a 4th Ray Amputation WilliamJudson IV, D.O.1, John Murphy, D.O.1, Phillip Sussman, D.O.1, John Harker D.O.1 HCA Healthcare/USF Morsani College of Medicine GME Programs/Largo Medical Center Background Treatment • Prevotella bivia is an anaerobic, non-pigmented, Gram-negative bacillus species that is known to inhabit the human female vaginal tract and oral flora. It is most commonly associated with endometritis and pelvic inflammatory disease.1, 2 • Rarely, P. bivia has been found in the nail bed, chest wall, intervertebral discs, and hip and knee joints.1 The bacteria has been linked to necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis.3, 4 • Only 3 other reports have described P. bivia infections in the upper Figure 1: Dorsum of the right hand on Figure 2: Ulnar aspect of right 4th and 5th Figures 13 and 14: Most recent images of patients hand in March, 2020. 2 presentation fingers Wound over the dorsum of the hand completely healed. Patient with flexion extremity with one patient requiring amputation , and one with deep soft contractures of remaining digits. tissue infection requiring multiple debridements and extensive tenosynovectomy.5 Discussion • Delays in diagnosis are common due to P. bivia’s long incubation period • P. bivia infections, although rare in orthopedic practice, can lead to and association with aerobic organisms that more commonly cause soft extensive debridements and possible amputation leading to great tissue infections leading to inappropriate antibiotic coverage. morbidity when affecting the upper extremities.1, 2, 5 • Here we present a case on P. -

Research Article Enterotype Bacteroides Is Associated with a High Risk in Patients with Diabetes: a Pilot Study

Hindawi Journal of Diabetes Research Volume 2020, Article ID 6047145, 11 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6047145 Research Article Enterotype Bacteroides Is Associated with a High Risk in Patients with Diabetes: A Pilot Study Jiajia Wang,1,2,3 Wenjuan Li,1,2,3 Chuan Wang,1,2,3 Lingshu Wang,1,2,3 Tianyi He,1,2,3 Huiqing Hu,1,2,3 Jia Song,1,2,3 Chen Cui,1,2,3 Jingting Qiao,1,2,3 Li Qing,1,2,3 Lili Li,1,2,3 Nan Zang,1,2,3 Kewei Wang,1,2,3 Chuanlong Wu,1,2,3 Lin Qi,1,2,3 Aixia Ma ,1,2,3 Huizhen Zheng,1,2,3 Xinguo Hou ,1,2,3 Fuqiang Liu ,1,2,3 and Li Chen 1,2,3 1Department of Endocrinology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China 250012 2Institute of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China 250012 3Key Laboratory of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, Shandong Province Medicine & Health, Jinan, Shandong, China 250012 Correspondence should be addressed to Fuqiang Liu; [email protected] and Li Chen; [email protected] Received 28 July 2019; Revised 14 November 2019; Accepted 19 November 2019; Published 22 January 2020 Academic Editor: Jonathan M. Peterson Copyright © 2020 Jiajia Wang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Background. More and more studies focus on the relationship between the gastrointestinal microbiome and type 2 diabetes, but few of them have actually explored the relationship between enterotypes and type 2 diabetes. -

Prevotella Intermedia

The principles of identification of oral anaerobic pathogens Dr. Edit Urbán © by author Department of Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine ESCMID Online University of Lecture Szeged, Hungary Library Oral Microbiological Ecology Portrait of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) by Jan Verkolje Leeuwenhook in 1683-realized, that the film accumulated on the surface of the teeth contained diverse structural elements: bacteria Several hundred of different© bacteria,by author fungi and protozoans can live in the oral cavity When these organisms adhere to some surface they form an organizedESCMID mass called Online dental plaque Lecture or biofilm Library © by author ESCMID Online Lecture Library Gram-negative anaerobes Non-motile rods: Motile rods: Bacteriodaceae Selenomonas Prevotella Wolinella/Campylobacter Porphyromonas Treponema Bacteroides Mitsuokella Cocci: Veillonella Fusobacterium Leptotrichia © byCapnophyles: author Haemophilus A. actinomycetemcomitans ESCMID Online C. hominis, Lecture Eikenella Library Capnocytophaga Gram-positive anaerobes Rods: Cocci: Actinomyces Stomatococcus Propionibacterium Gemella Lactobacillus Peptostreptococcus Bifidobacterium Eubacterium Clostridium © by author Facultative: Streptococcus Rothia dentocariosa Micrococcus ESCMIDCorynebacterium Online LectureStaphylococcus Library © by author ESCMID Online Lecture Library Microbiology of periodontal disease The periodontium consist of gingiva, periodontial ligament, root cementerum and alveolar bone Bacteria cause virtually all forms of inflammatory -

A Genomic Journey Through a Genus of Large DNA Viruses

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Virology Papers Virology, Nebraska Center for 2013 Towards defining the chloroviruses: a genomic journey through a genus of large DNA viruses Adrien Jeanniard Aix-Marseille Université David D. Dunigan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] James Gurnon University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Irina V. Agarkova University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Ming Kang University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/virologypub Part of the Biological Phenomena, Cell Phenomena, and Immunity Commons, Cell and Developmental Biology Commons, Genetics and Genomics Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Immunology Commons, Medical Pathology Commons, and the Virology Commons Jeanniard, Adrien; Dunigan, David D.; Gurnon, James; Agarkova, Irina V.; Kang, Ming; Vitek, Jason; Duncan, Garry; McClung, O William; Larsen, Megan; Claverie, Jean-Michel; Van Etten, James L.; and Blanc, Guillaume, "Towards defining the chloroviruses: a genomic journey through a genus of large DNA viruses" (2013). Virology Papers. 245. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/virologypub/245 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Virology, Nebraska Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Virology Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Adrien Jeanniard, David D. Dunigan, James Gurnon, Irina V. Agarkova, Ming Kang, Jason Vitek, Garry Duncan, O William McClung, Megan Larsen, Jean-Michel Claverie, James L. Van Etten, and Guillaume Blanc This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ virologypub/245 Jeanniard, Dunigan, Gurnon, Agarkova, Kang, Vitek, Duncan, McClung, Larsen, Claverie, Van Etten & Blanc in BMC Genomics (2013) 14. -

The Influence of Sodium Chloride on the Performance of Gammarus Amphipods and the Community Composition of Microbes Associated with Leaf Detritus

THE INFLUENCE OF SODIUM CHLORIDE ON THE PERFORMANCE OF GAMMARUS AMPHIPODS AND THE COMMUNITY COMPOSITION OF MICROBES ASSOCIATED WITH LEAF DETRITUS By Shelby McIlheran Leaf litter decomposition is a fundamental part of the carbon cycle and helps support aquatic food webs along with being an important assessment of the health of rivers and streams. Disruptions in this organic matter breakdown can signal problems in other parts of ecosystems. One disruption is rising chloride concentrations. Chloride concentrations are increasing in many rivers worldwide due to anthropogenic sources that can harm biota and affect ecosystem processes. Elevated chloride concentrations can lead to lethal or sublethal impacts. While many studies have shown that excessive chloride uptake impacts health (e.g. lowered respiration and growth rates) in a wide variety of aquatic organisms including microbes and benthic invertebrates). The impacts of high chloride concentrations on decomposers are less well understood. My research objective was to assess how increasing chloride concentrations affect the performance and diversity of decomposer organisms in freshwater systems. I experimentally manipulated chloride concentrations in microcosms containing leaves colonized by microbes or containing leaves, microbes and amphipods. Respiration rate, decomposition, and community composition of the microbes were measured along with the amphipod growth rate, egestion rate, and mortality. Elevated chloride concentration did not impact microbial respiration rates or leaf decomposition, but had large impacts on bacteria community composition. It did cause a decrease in instantaneous growth rate, and 100% mortality in the highest amphipod chloride treatment, but amphipod egestion rate was not significantly affected. The results of my research suggest that the widespread increases in chloride concentrations in rivers will have an impact on decomposer communities in these systems.