Film Synopsis Historical Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

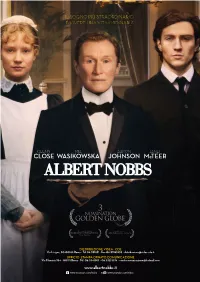

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

The Image of Man in Metafictional Novels by John Banville: Celebrating the Power of the Imagination

ROCZNIKI HUMANISTYCZNE Tom LXI, zeszyt 5 – 2013 MACIEJ CZERNIAKOWSKI * THE IMAGE OF MAN IN METAFICTIONAL NOVELS BY JOHN BANVILLE: CELEBRATING THE POWER OF THE IMAGINATION A b s t r a c t. THe essay analyzes How JoHn Banville reconstructs tHe image of man in His two novels Kepler and Doctor Copernicus by means of broadly understood metafiction. The Author of tHe essay discusses tHe following elements: implied autHor’s and narrator’s power of creative imagination and RHeticus’s self-consciousness wHicH enables to create fiction and intertextuality of tHe novel. WHen analyzing tHe last aspect of tHe novels, tHe AutHor mentions also MicHel Foucault’s term, Heterotopia. THe results of tHis analysis are twofold. On tHe one Hand, man Has got practically unlimited creative imagination on tHeir part. On tHe otHer Hand, man seems to be lost in tHe world of unclear ontological boundaries, wHicH proves a paradoxical image of man. In tHe critical works approacHing Doctor Copernicus and Kepler as metafictions, tHat is “fictional writing wHicH self-consciously and systematically draws atten- tion to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about tHe relationsHip between fiction and reality” (2), critics most often comment on tHese two novels in a fairly general way. For instance, Eve Patten explains tHat “[m]etafictional and pHilosopHical writing in Ireland continues to be dominated . by JoHn Banville (b. 1945). Since tHe mid1980s, Banville’s fiction Has continued its analysis of alternative languages and structures of perception” (272). JosepH McMinn also concentrates on language, claiming tHat it “is largely self-referential and simply cannot contain or explain tHe world outside itself, tHis body of work belongs firmly in tHe international context of postmodernism, botH stylistically and pHilo- sopHically” (“Versions of Banville” 87). -

The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 Pages

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 4 8-18-2006 The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. Matthew rB own University of Massachusetts – Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Brown, Matthew (2006) "The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. $23.00. Matthew Brown, University of Massachusetts-Boston To the surprise of many, John Banville's The Sea won the 2005 Booker prize for fiction, surprising because of all of Banville's dazzlingly sophisticated novels, The Sea seems something of an afterthought, a remainder of other and better books. Everything about The Sea rings familiar to readers of Banville's oeuvre, especially its narrator, who is enthusiastically learned and sardonic and who casts weighty meditations on knowledge, identity, and art through the murk of personal tragedy. This is Max Morden, who sounds very much like Alexander Cleave from Eclipse (2000), or Victor Maskell from The Untouchable (1997). -

“The Ghost of That Ineluctable Past”: Trauma and Memory in John Banville’S Frames Trilogy GPA: 3.9

“THE GHOST OF THAT INELUCTABLE PAST”: TRAUMA AND MEMORY IN JOHN BANVILLE’S FRAMES TRILOGY BY SCOTT JOSEPH BERRY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English December, 2016 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Jefferson Holdridge, PhD, Advisor Barry Maine, PhD, Chair Philip Kuberski, PhD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To paraphrase John Banville, this finished thesis is the record of its own gestation and birth. As such, what follows represents an intensely personal, creative journey for me, one that would not have been possible without the love and support of some very important people in my life. First and foremost, I would like to thank my wonderful wife, Kelly, for all of her love, patience, and unflinching confidence in me throughout this entire process. It brings me such pride—not to mention great relief—to be able to show her this work in its completion. I would also like to thank my parents, Stephen and Cathyann Berry, for their wisdom, generosity, and support of my every endeavor. I am very grateful to Jefferson Holdridge, Omaar Hena, Mary Burgess-Smyth, and Kevin Whelan for their encouragement, mentorship, and friendship across many years of study. And to all of my Wake Forest friends and colleagues—you know who you are—thank you for your companionship on this journey. Finally, to Maeve, Nora, and Sheilagh: Daddy finally finished his book. Let’s go play. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv -

GENRE and CODE in the WORK of JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle

GENRE AND CODE IN THE WORK OF JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra Dublin City University School of Humanities Department of English Supervisor: Dr Derek Hand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD April 2016 I hereby certify that this material, which T now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_____________________________ ID No.: 59267054_______ Date: Table of contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction: Genre and the Intertcxlual aspects of Banville's writing 5 The Problem of Genre 7 Genre Theory 12 Transgenerie Approach 15 Genre and Post-modernity' 17 Chapter One: The Benjamin Black Project: Writing a Writer 25 Embracing Genre Fiction 26 Deflecting Criticism from Oneself to One Self 29 Banville on Black 35 The Crossover Between Pseudonymous Authorial Sell'and Characters 38 The Opposition of Art and Craft 43 Change of Direction 45 Corpus and Continuity 47 Personae Therapy 51 Screen and Page 59 Benjamin Black and Ireland 62 Guilt and Satisfaction 71 Real Individuals in the Black Novels 75 Allusions and Genre Awareness 78 Knowledge and Detecting 82 Chapter Two: Doctor Copernicus, Historical Fiction and Post-modernity: -

Scientific and Historical Paradigms in John Banville's Doctor Copernicus

Keeping our Nerve: Scientific and Historical Paradigms in John Banville’s Doctor Copernicus Lucia Boldrini University of London [email protected] Drawing on Collingwood and Kuhn, the article shows how Banville’s 1976 Doctor Copernicus delineates a scientific / historical “paradigm” by linking the “revolutions” of early modernity to the crisis of knowledge of the latter part of the 20th century, emphasising the need for historical awareness. Key words: literature and history / historiography / historical novel / science / scientific paradigm / Copernican turn / Banville, John UDK 82.0:930.85 82.0:001 In the chapter “The Historical Imagination” of his now classic The Idea of History,1 R. G. Collingwood identifies historical thought as the domi- nant interest of modernity. History, he argues, has evolved since early mo- dernity a technique no less structured and certain than that of her “elder sister,” physical science, which dominated thought in the seventeenth cen- tury (Collingwood 232). But Collingwood rejects what he calls the “com- mon-sense theory” of history, according to which the historian relies on documentary sources to record facts objectively as they have happened. By recognising that, for the historian, imagination in the (re)construction of historical events is “not ornamental but structural” and “a priori” (241), and that the historian himself – rather than (presumed) objective facts – is his own ultimate authority, “it is possible to effect what one might call a Copernican revolution in the theory of history” (236). For us, steeled in the (post)structuralist and postmodern debates of the second half of the last century, the withdrawal of authoritative status from historical fact may not seem so bold a move. -

Beckettian Irony in the Work of Paul Auster, John Banville and J.M

‘Permanent Parabasis’: Beckettian Irony in the Work of Paul Auster, John Banville and J.M. Coetzee Michael Springer Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of English and Related Literature April 2014 iii Abstract This thesis considers the influence of the writing of Samuel Beckett on that of Paul Auster, John Banville and J.M. Coetzee through the lens of Romantic irony, as formulated by Friedrich Schlegel and, later, Paul de Man. The broad argument is that the form of irony first articulated by the Jena Romantics is brought in Beckett’s work to something of an extreme, and that this extremity represents both one of his most characteristic achievements and a unique and specifically troublesome challenge for those who come after him. The thesis hence explores how Auster, Banville and Coetzee respond to and negotiate this irony in their own work, and contrasts their respective responses. Put briefly, I find that all three writers to one extent or another deflect Beckett’s irony, while engaging with it: Auster adopts certain stylistic and structural aspects of Beckett’s work, but on the whole reaches fundamentally different epistemological and existential conclusions; Banville engages closely with the epistemological and existential challenge posed by Beckett’s irony, and attempts to balance this with a contrasting sense of the capacity of art and the imagination to make meaning of the world; and Coetzee, after an initial attempt at stylistic imitation, moves away from this but remains fundamentally influenced by certain insights -

1 Introduction 2 Banville's Narcissists

Notes 1 Introduction 1. There is a degree of uniformity to these characters, their situations and their mindsets, that allows us to speak of a typical Banville protagonist with as much legitimacy as we may speak of a typical Beckett or Kafka protagonist. There is an undeniable continuity – much more pronounced than mere fictional family resemblance – between all of Banville’s pro- tagonists, stretching arguably from Nightspawn’s Ben White, but certainly from Freddie Montgomery in The Book of Evidence, to The Sea’s Max Morden. 2. Freud’s first use of the term ‘narcissism’ appears in a footnote added in 1910 to his ‘Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality’, to denote a phase in the development of male homosexuality. His interpretation of the classical myth is, in this sense, quite a literal one. 2 Banville’s Narcissists 1. This article of faith is one which character and creator evidently hold in common. In the essay ‘Making Little Monsters Walk’, Banville delivers the following series of excessively lofty aphoristic paradoxes: ‘Nietzsche was the first to recognize that the true depth of a thing is in its surface. Art is shallow, and therein lies its deeps. The face is all, and, in front of the face, the mask.’ (Banville, 1993c: 108). 2. Kleist and Amphitryon have proven enduring inspirations for Banville. The Infinities is plainly based on the story, and contains a number of meta- fictional allusions not just to the story itself, but to Banville’s own, not particularly successful, stage adaptation of it. One of the novel’s central characters, the actress Helen, is preparing for her role as Amphitryon’s wife Alcemene in the play. -

John Banville's Scientific Art

Colby Quarterly Volume 31 Issue 1 March Article 9 March 1995 Pattern in Chaos: John Banville's Scientific Art Brian McIlroy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 31, no.1, March 1995, p.74-80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. McIlroy: Pattern in Chaos: John Banville's Scientific Art Pattern in Chaos: John Banville's Scientific Art by BRIAN MCILROY I think that the illustration ofthe scientific method as it applies to chaos theory properly stresses the important element of play in creative activity. But any other growing point of science or the arts would exhibit this same vital element. We need to play because logic is such a feeble and restricting tool. Play liberates the imagination, throwing truly surprising things into the air. The trick-and it is a very difficult trick-is to pick the significant from the trivial in the grab bag ofnovelties brought to light by play. This requires that the creative individual-scientist or artist-be alert to subtle symmetries. We can find only what we are looking for. What we are looking for, if it is to have importance, should be based on insights that extend beyond the corner of the laboratory or studio where we engage in our work. We are guided in our assessment ofwhat is or is not significant by all that has been revealed to us in every branch ofcontemporary culture. -

John Banville and His Romantic Quest

Linguistics and Literature Studies 6(5): 236-241, 2018 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2018.060506 John Banville and His Romantic Quest Wang Jing School of Foreign Languages, Soochow University, Jiangsu, China Copyright©2018 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract John Banville, one of Ireland’s most serious tendency towards the Romantic tradition. In the following and gifted writers, shares the belief of modernist writers sections, this thesis will study Banville’s fiction from a that the modern society alienates mankind through its Romantic perspective, aiming to reveal how Banvill chaos, madness and sterility, but denies the fatalist idea that returns to Romanticism and pursues a romantic quest. By this society is hopelessly doomed. He, therefore, pursues a examining his various books, this thesis will discuss how romantic quest in his fiction by resorting to nostalgia, Banville looks for a spiritual home by writing about nature and imagination. This thesis will study Banville’s nostalgia, nature and highlighting imagination. fiction from a Romantic perspective, aiming to reveal how Banvill returns to Romanticism and pursues a romantic quest. By examining his various books, this thesis will 2. Nostalgia discuss how Banville looks for a spiritual home by writing about nostalgia, nature and highlighting imagination. It Banville favors writing about the past. In most of his concludes that the utopian world created by Banville for his books, readers may be deeply touched by a yearning for the protagonists, cannot solve all problems in reality. -

Scientific Art: the Tetralogy of John Banville

SCIENTIFIC ART: THE TETRALOGY OF JOHN BANVILLE by BRIAN STEPHEN McILROY B.A. (Hons.) Sheffield University, 1981 M.A. Leeds University, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1991 (cT)Brian S. Mcllroy, 1991 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date IS /V'l <Wl DE-6G/811 r ii Abstract The main thesis of this study is that John Banville's fictional scientific tetralogy makes an aesthetically challenging attempt to fuse renewed popular notions of science and scientific figures with renewed artistic forms. Banville is most interested in the creative mind of the scientist, astronomer, or mathematician, his life and times in Doctor Copernicus (1976) and Kepler (1981) , and his modern day influence in The Newton Letter (1982) and Mefisto (1986). The novelist's writing is a movement of the subjective into what has normally been regarded as the objective domain of science.