Legitimizing the Artist: Avant-Garde Utopianism and Relational Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Futurism's Photography

Futurism’s Photography: From fotodinamismo to fotomontaggio Sarah Carey University of California, Los Angeles The critical discourse on photography and Italian Futurism has proven to be very limited in its scope. Giovanni Lista, one of the few critics to adequately analyze the topic, has produced several works of note: Futurismo e fotografia (1979), I futuristi e la fotografia (1985), Cinema e foto- grafia futurista (2001), Futurism & Photography (2001), and most recently Il futurismo nella fotografia (2009).1 What is striking about these titles, however, is that only one actually refers to “Futurist photography” — or “fotografia futurista.” In fact, given the other (though few) scholarly studies of Futurism and photography, there seems to have been some hesitancy to qualify it as such (with some exceptions).2 So, why has there been this sense of distacco? And why only now might we only really be able to conceive of it as its own genre? This unusual trend in scholarly discourse, it seems, mimics closely Futurism’s own rocky relationship with photography, which ranged from an initial outright distrust to a later, rather cautious acceptance that only came about on account of one critical stipulation: that Futurist photography was neither an art nor a formal and autonomous aesthetic category — it was, instead, an ideological weapon. The Futurists were only able to utilize photography towards this end, and only with the further qualification that only certain photographic forms would be acceptable for this purpose: the portrait and photo-montage. It is, in fact, the very legacy of Futurism’s appropriation of these sub-genres that allows us to begin to think critically about Futurist photography per se. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Suzanne Preston Blier Picasso’S Demoiselles

Picasso ’s Demoiselles The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece Suzanne PreSton Blier Picasso’s Demoiselles Blier_6pp.indd 1 9/23/19 1:41 PM The UnTold origins of a Modern MasTerpiece Picasso’s Demoiselles sU zanne p res T on Blie r Blier_6pp.indd 2 9/23/19 1:41 PM Picasso’s Demoiselles Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 Blier_6pp.indd 3 9/23/19 1:41 PM © 2019 Suzanne Preston Blier All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Drew Sisk. Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill. Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro and The Sans byBW&A Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Blier, Suzanne Preston, author. Title: Picasso’s Demoiselles, the untold origins of a modern masterpiece / Suzanne Preston Blier. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018047262 (print) LCCN 2019005715 (ebook) ISBN 9781478002048 (ebook) ISBN 9781478000051 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478000198 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973. Demoiselles d’Avignon. | Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973—Criticism and interpretation. | Women in art. | Prostitution in art. | Cubism—France. Classification: LCC ND553.P5 (ebook) | LCC ND553.P5 A635 2019 (print) | DDC 759.4—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047262 Cover art: (top to bottom): Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, detail, March 26, 1907. Museum of Modern Art, New York (Online Picasso Project) opp.07:001 | Anonymous artist, Adouma mask (Gabon), detail, before 1820. Musée du quai Branly, Paris. Photograph by S. P. -

Federico Luisetti, “A Futurist Art of the Past”, Ameriquests 12.1 (2015)

Federico Luisetti, “A Futurist Art of the Past”, AmeriQuests 12.1 (2015) A Futurist Art of the Past: Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s Photodynamism Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Un gesto del capo1 Un gesto del capo (A gesture of the head) is a rare 1911 “Photodynamic” picture by Anton Giulio Bragaglia (1890-1960), the Rome-based photographer, director of experimental films, gallerist, theater director, and essayist who played a key role in the development of the Italian Avant- gardes. Initially postcard photographs mailed out to friends, Futurist Photodynamics consist of twenty or so medium size pictures of small gestures (greeting, nodding, bowing), acts of leisure, work, or movements (typing, smoking, a slap in the face), a small corpus that preceded and influenced the experimentations of European Avant-garde photography, such as Christian Schad’s Schadographs, Man Ray’s Rayographs, and Lazlo Moholy-Nagy’s Photograms. Thanks to historians of photography, in particular Giovanni Lista and Marta Braun, we are familiar with the circumstances that led to the birth of Photodynamism, which took on and transformed the principles proclaimed in the April 11, 1910 Manifesto tecnico della pittura futurista (Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting) by Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini, where the primacy of movement and the nature of “dynamic sensation” challenge the conventions of traditional visual arts: “The gesture which we would reproduce on canvas shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be 1 (A Gesture of the Head), 1911. Gelatin silver print, 17.8 x 12.7 cm, Gilman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]. -

Lesson Plan: George L.K. Morris and Cubism

George L.K. Morris Who was George L.K. Morris and what is Cubism? Duration: 45 minutes Grade Level: Grades 2 – 8 Learning Objectives: • Learn about the life of George L.K. Morris • Study what the art movement Cubism is • Learn what influences an artist’s work Outcomes: • Students will learn about Cubism and its two distinct movements • Students will study how relationships and life experience influenced an artist’s work • Students will engage in critical thinking and visual skills by analyzing artwork Associated Activities: • Cubism Coloring Pages, 30 minutes • Recycled Robot, 45 minutes George L.K. Morris and Cubism Lesson Plan Learn more: mattmuseum.org/the-matt-at-home/ Page 1 Who was George L.K. Morris? Morris was born in New York City on November 14, 1905. Morris attended Groton School, and then graduated from Yale University in 1928. From 1928 to 1929, he studied Realism at the Art Students League of New York under painters John French Sloan and Kenneth Hayes Miller. In 1929, he traveled to Paris, where he continued his studies with Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant. It was there that he became a confirmed abstractionist. In 1935, he married fellow artist, Suzy Frelinghuysen. In 1936, he became one of the founding members of the American Abstract Artists and served as its president in the 1940s. He and his wife were part of the Park Avenue Cubists, a group of four artists who came from affluent backgrounds. Morris is best known for his Cubist sculptures and paintings. Courtesy Frelinghuysen Morris House & Studio George L.K. -

1874 – 2019 • Impressionism • Post-Impressionism • Symbolism

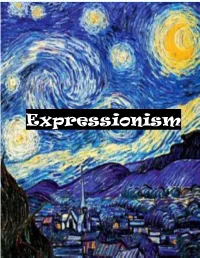

1874 – 2019 “Question: Why can’t art be beautiful instead of fascinating? Answer: Because the concept of beautiful is arguably more subjective for each viewer.” https://owlcation.com/humanities/20th-Century-Art-Movements-with-Timeline • Impressionism • Dada • Post-Impressionism • Surrealism • Symbolism • Abstract Expressionism • Fauvism • Pop Art • Expressionism • Superrealism • Cubism • Post-Modernism • Futurism • Impressionism is a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter • Post-Impressionism is an art movement that developed in the 1890s. It is characterized by a subjective approach to painting, as artists opted to evoke emotion rather than realism in their work • Symbolism, a loosely organized literary and artistic movement that originated with a group of French poets in the late 19th century, spread to painting and the theatre, and influenced the European and American literatures of the 20th century to varying degrees. • Fauvism is the style of les Fauves (French for "the wild beasts"), a group of early twentieth- century modern artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities and strong color over the representational or realistic values retained by Impressionism. • Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. ... Expressionist artists have sought to express the meaning of emotional experience rather than physical reality. • Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related movements in music, literature and architecture. -

The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5786 Chapter 3: The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century Introduction Quality in art is not just a matter of private experience. There is a consensus of taste. Clement Greenberg1 Important works of art embody important innovations. The most important works of art are those that announce very important innovations. There is considerable interest in identifying the most important artists, and their most important works, not only among those who study art professionally, but also among a wider public. The distinguished art historian Meyer Schapiro recognized that this is due in large part to the market value of works of art: “The great interest in painting and sculpture (versus poetry) arises precisely from its unique character as art that produces expensive, rare, and speculative commodities.”2 Schapiro’s insight suggests one means of identifying the most important artists, through analysis of prices at public sales.3 This strategy is less useful in identifying the most important individual works of art, however, for these rarely, if ever, come to market. An alternative is to survey the judgments of art experts. One way to do this is by analyzing textbooks. -

Expressionism

Expressionism Expressionism Painting 2017-18 Critique for Project and Research Monday March 5th Learning Objectives: 1. Explore experimental methods with paint and develop authentic gestural brushwork or mark making 2. Make a connection to an Expressionism artist(s) between 1850-1945 a. Collect contextual information b. Perform a formal analysis 3. Develop your theme by adding a source (inspired by the TOK diagram) 4. Make a work of art which showcases authentic mark making and original content Point Distribution out of 100 A. Art Journal 50pts Artwork 50pts Rubrics used: IB Rubric and this document Note: cite your sources, number pages in lower right, date pages upper left, turn journal horizontal __________________________________________________________________________ *Schedule we are going to use Scheduling Note: if you fall behind, then you have homework* Day1-2 Presentation to students on Impressionism to Neo Expressionism. Define new vocabulary. Day 3, 4 Explore and record experimental methods with paint and find your authentic mark. Make a tile to donate to the class. Day 5-8 Decide on an artist to perform contextual and formal analysis. Explain how this artist informs your practice. Mimic a portion of the artist’s work. Day 9-11 Make a page proposing the ‘form’ and ‘content’ of your project in words and pictures Annotate and make connections to a source, which further develops your theme. Day 12-20 Paint Your Final Work – Demonstrate New Skills and new understanding about your theme Document your progress through 3 or more pictures while reflecting on the work’s development Day 21 Reflect on final outcomes and include a picture of the final work. -

A Guide to Impressionism

A Guide to Impressionism Learn about the history and artistic style of the Impressionists in this teacher’s resource. Find out why the Impressionists were considered so shocking and how they have influenced art over a hundred years later. Explore the art of Monet, Renoir, Degas, and more! Grade Level: Adult, College, Grades 6-8, Grades 9-12 Collection: European Art, Impressionism Culture/Region: Europe Subject Area: Fine Arts, History and Social Science, Visual Arts Activity Type: Art in Depth THE SHOCKING NEW ART MOVEMENT The word “impressionism” makes most people think of beautiful, sunlit paintings of the French countryside; glorious gardens and lily ponds; and fashionable Parisians enjoying life in charming cafes. But in 1874, when the men and women who came to be known as the Impressionists first exhibited their work, their style of painting was considered shocking and outrageous by all but the most forward-thinking viewers. Why did these young artists cause such an uproar? The following comparison shows how their radical ideas, techniques, and subjects broke the time-honored rules and traditions of art in late 19th-century France. “What do we see in the work of these men? Nothing but defiance, almost an insult to the tastes and intelligence of the public.” -Etienne Carjat, “L’exposition du bouldevard des Capucines,” Le Patriote Francais (1874) “There is little doubt that Impressionist landscape paintings are the most…appreciated works of art ever produced.” –Richard Brettell and Scott Schaefer, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape The accepted style of painting often featured: Great historical subjects or mythological scenes that were meant to be morally uplifting; An emphasis on line, filled in with color; Smooth, almost invisible brushstrokes; Paintings primarily done in the artist’s studio The Judgment of Paris François-Xavier Fabre, 1808 Oil on canvass Adolph D.