Suzanne Preston Blier Picasso’S Demoiselles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picasso Au Lapin Agile Et Picasso at the Lapin Agile Patricia Belzil

Document generated on 09/26/2021 7:53 p.m. Jeu Revue de théâtre Deux Elvis pour deux solitudes Picasso au Lapin Agile et Picasso at the Lapin Agile Patricia Belzil Le théâtre à Québec Number 86 (1), 1998 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/25628ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc. ISSN 0382-0335 (print) 1923-2578 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Belzil, P. (1998). Review of [Deux Elvis pour deux solitudes : Picasso au Lapin Agile et Picasso at the Lapin Agile]. Jeu, (86), 31–34. Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc., 1998 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ PATRICIA BELZIL Deux Elvis pour deux solitudes quelques mois d'intervalle étaient présentées, en 1997, deux productions mon Atréalaises de la comédie de l'acteur américain Steve Martin : Picasso au Lapin Agile et Picasso at the Lapin Agile, pour satisfaire les deux solitudes. Il y avait là une occasion assez rare de comparer le regard que peuvent porter les Québécois franco phones et anglophones sur le Paris du début du siècle, et de voir que la langue et la culture, au-delà du partage d'un espace géopolitique, conditionnent notre vision du monde. -

Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino: Full Transcript of the Interview

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH FASHION Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino C1046/09 IMPORTANT Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 [0]20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. THE NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET Ref. No.: C1046/09 Playback No.: F15198-99; F15388-90; F15531-35; F15591-92 Collection title: An Oral History of British Fashion Interviewee’s surname: Savage Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: Percy Sex: Occupation: Date of birth: 12.10.1926 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Date(s) of recording: 04.06.2004; 11.06.2004; 02.07.2004; 09.07.2004; 16.07.2004 Location of interview: Name of interviewer: Linda Sandino Type of recorder: Marantz Total no. of tapes: 12 Type of tape: C60 Mono or stereo: stereo Speed: Noise reduction: Original or copy: original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interview is open. Copyright of BL Interviewer’s comments: Percy Savage Page 1 C1046/09 Tape 1 Side A (part 1) Tape 1 Side A [part 1] .....to plug it in? No we don’t. Not unless something goes wrong. [inaudible] see well enough, because I can put the [inaudible] light on, if you like? Yes, no, lovely, lovely, thank you. -

FAMÍLIA DE SALTIMBANQUIS DE PICASSO Context Biogràfic, Artístic I Interpretatiu

FAMÍLIA DE SALTIMBANQUIS DE PICASSO Context biogràfic, artístic i interpretatiu Assumpció Cardona Iglésias TFG Tutora: Teresa M. Sala Història de l´Art. Universitat de Barcelona, 2018 INDEX INTRODUCCCIÓ: Objectius i metodologia .................................................................................... 4 Comentari de les fonts bibliogràfiques ......................................................................................... 6 I.CONTEXT BIOGRÀFIC I ARTÍSTIC . ETAPA ENTRE BARCELONA I PARÍS ................................... 13 1.1.Barcelona 1895-1904 ........................................................................................................ 13 1.2.Influència de Rusiñol ......................................................................................................... 14 1.3.Viatges a París ................................................................................................................... 16 1.4.París 1904-1905................................................................................................................. 17 II. FAMÍLIA DE SALTIMBANQUIS .................................................................................................. 19 2.1. Etapa rosa ......................................................................................................................... 19 2.1.1. Del blau al rosa .......................................................................................................... 19 2.1.2.Començament etapa rosa ......................................................................................... -

Gelett Burgess - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Gelett Burgess - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Gelett Burgess(30 January 1866 – 18 September 1951) Frank Gelett Burgess was an artist, art critic, poet, author and humorist. An important figure in the San Francisco Bay Area literary renaissance of the 1890s, particularly through his iconoclastic little magazine, The Lark, he is best known as a writer of nonsense verse. He was the author of the popular Goops books, and he invented the blurb. <b>Early life</b> Born in Boston, Burgess was "raised among staid, conservative New England gentry". He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduating with a B.S. in 1887. After graduation, Burgess fled conservative Boston for the livelier bohemia of San Francisco, where he took a job working as a draftsman for the Southern Pacific Railroad. In 1891, he was hired by the University of California at Berkeley as an instructor of topographical drawing. <b>Cogswell fountain incident</b> In 1894, Burgess lost his job at Berkeley as a result of his involvement in an attack on one of San Francisco's three Cogswell fountains, free water fountains named after the pro-temperance advocate Henry Cogswell who had donated them to the city in 1883. As the San Francisco Call noted a year before the incident, Cogswell's message, combined with his enormous image, irritated many: <i>It is supposed to convey a lesson on temperance, as the doctor stands proudly on the pedestal, with his whiskers flung to the rippling breezes. In his right hand he holds a temperance pledge rolled up like a sausage, and the other used to contain a goblet overflowing with heaven's own nectar. -

Jean METZINGER (Nantes 1883 - Paris 1956)

Jean METZINGER (Nantes 1883 - Paris 1956) The Yellow Feather (La Plume Jaune) Pencil on paper. Signed and dated Metzinger 12 in pencil at the lower left. 315 x 231 mm. (12 3/8 x 9 1/8 in.) The present sheet is closely related to Jean Metzinger’s large painting The Yellow Feather, a seminal Cubist canvas of 1912, which is today in an American private collection. The painting was one of twelve works by Metzinger included in the Cubist exhibition at the Salon de La Section d’Or in 1912. One of the few paintings of this period to be dated by the artist, The Yellow Feather is regarded by scholars as a touchstone of Metzinger’s early Cubist period. Drawn with a precise yet sensitive handling of fine graphite on paper, the drawing repeats the multifaceted, fragmented planes of the face in the painting, along with the single staring eye, drawn as a simple curlicue. The Yellow Feather was one of several Cubist paintings depicting women in fashionable clothes, and with ostrich feathers in their hats, which were painted by Metzinger in 1912 and 1913. Provenance: alerie Hopkins-Thomas, Paris Private collection, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, until 2011. Literature: Jean-Paul Monery, Les chemins de cubisme, exhibition catalogue, Saint-Tropez, 1999, illustrated pp.134-135; Anisabelle Berès and Michel Arveiller, Au temps des Cubistes, 1910-1920, exhibition catalogue, Paris, 2006, pp.428-429, no.180. Artist description: Trained in the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, Jean Metzinger sent three paintings to the Salon des Indépendants in 1903 and, having sold them, soon thereafter settled in Paris. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

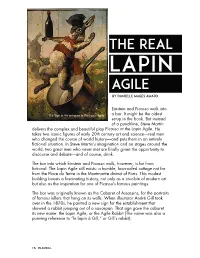

The Real Lapin Agile

THE REAL LAPIN AGILE By Danielle Mages Amato Einstein and Picasso walk into The Sign at the entrance to The Lapin Agile a bar. It might be the oldest setup in the book. But instead of a punchline, Steve Martin delivers the complex and beautiful play Picasso at the Lapin Agile . He takes two iconic figures of early 20th century art and science—real men who changed the course of world history—and puts them in an entirely fictional situation. In Steve Martin’s imagination and on stages around the world, two great men who never met are finally given the opportunity to discourse and debate—and of course, drink. The bar into which Einstein and Picasso walk, however, is far from fictional. The Lapin Agile still exists: a humble, low-roofed cottage not far from the Place du Tertre in the Montmartre district of Paris. This modest building boasts a fascinating history, not only as a crucible of modern art but also as the inspiration for one of Picasso’s famous paintings. The bar was originally known as the Cabaret of Assassins, for the portraits of famous killers that hung on its walls. When illustrator André Gill took over in the 1870s, he painted a new sign for the establishment that showed a rabbit jumping out of a saucepan. That sign gave the cabaret its new name: the Lapin Agile, or the Agile Rabbit (The name was also a punning reference to “le lapin à Gill,” or Gill’s rabbit). 15 PLAYBILL Pable Picasso's painting Au Lapin Agile. -

Proquest Dissertations

Joyce Mansour's poetics: A discourse of plurality by a second-generation surrealist poet Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bachmann, Dominique Groslier Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 06:15:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280687 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

NEO-Orientalisms UGLY WOMEN and the PARISIAN

NEO-ORIENTALISMs UGLY WOMEN AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE, 1905 - 1908 By ELIZABETH GAIL KIRK B.F.A., University of Manitoba, 1982 B.A., University of Manitoba, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA . October 1988 <£> Elizabeth Gail Kirk, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date October, 1988 DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT The Neo-Orientalism of Matisse's The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, both of 1907, exists in the similarity of the extreme distortion of the female form and defines the different meanings attached to these "ugly" women relative to distinctive notions of erotic and exotic imagery. To understand Neo-Orientalism, that is, 19th century Orientalist concepts which were filtered through Primitivism in the 20th century, the racial, sexual and class antagonisms of the period, which not only influenced attitudes towards erotic and exotic imagery, but also defined and categorized humanity, must be considered in their historical context. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Montmartre the Tour: La Place Des Abbesses (The Abbesses Square), the Small Streets, La Place Du Tertre (The Tertre Square), Le Sacré-Coeur (The Sacred Heart)

MONTMARTRE THE TOUR: LA PLACE DES ABBESSES (THE ABBESSES SQUARE), THE SMALL STREETS, LA PLACE DU TERTRE (THE TERTRE SQUARE), LE SACRÉ-COEUR (THE SACRED HEART) LE SACRÉ-COEUR THE SMALL STREETS LA PLACE DU TERTRE LES ABBESSES Lenght: Means of locomotion: on foot - 3H00 walking, Access for persons with reduced - half a day: walking + visit of the mobility : no Sacré-Coeur, Total distance: 4km - the entire day: walking + visit of Starting point: Place des Abbesses the Sacré-Coeur, the Montmartre (metro line 12, Abbesses station, museum and the Dali area. or the Montmartrobus Abbesses station) Public: All restaurant, « Le Relais de la Butte » (The Mound Inn), once called « Chez Azon » (At Azon’s). At the beginning of the 20th century, Father Azon gladly welcomed and fed all the penniless artists from the bateau- lavoir who paid him with works of art... which did not prevent him from Take rue des Abbesses going bankrupt ! (Abbesses Street) on your right and keep going forward for about 50 Climb the steps of this Emile metres. Goudeau small square (ex Ravignan Square). It is the same quietness At the Abbesses passage entrance, impression that we found in the on your right, graffities, drawings, Place des Abbesses, with benches, stencils and other inlays are trees, the big Wallace fountain, and animating the walls. some funny graffities. Pay close attention, you will have the opportunity to see many others On your left, with your back turned throughout the walk. to the steps, stands a recently cleaned building with white blinds Carry on and take rue Ravignan and green doors is the famous (Ravignan Street) on your right.