NSIAD-90-208 Navy Ship Defense: Concerns About the Strategy For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messerschmitt Me 262

Messerschmitt Me 262 The Messerschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe / Sturmvogel (English: "Swallow"/ "Storm Bird") of Nazi Germany was the world's first operational jet- powered fighter aircraft. Design work started before World War II began, but engine problems and top-level interference kept the aircraft from operational status with the Luftwaffe until mid-1944. Heavily armed, it was faster than any Allied fighter, including the British jet-powered Gloster Meteor.One of the most advanced aviation designs in operational use during World War II,the Me 262 was used in a variety of roles, including light bomber, reconnaissance, and even experimental night fighter versions. Me 262 pilots claimed a total of 542 Allied kills, although higher claims are sometimes made. The Allies countered its potential effectiveness in the air by attacking the aircraft on the ground and during takeoff and landing. Engine reliability problems, from the pioneering nature of its Junkers Jumo 004 axial- flow turbojetengines—the first ever placed in mass production—and attacks by Allied forces on fuel supplies during the deteriorating late-war situation also reduced the effectiveness of the aircraft as a fighting force. In the end, the Me 262 had a negligible impact on the course of the war as a result of its late introduction and the consequently small numbers put in operational service. While German use of the aircraft ended with the close of the Second World War, a small number were operated by the Czechoslovak Air Force until 1951. Captured Me 262s were studied and flight tested by the major powers, and ultimately influenced the designs of a number of post-war aircraft such as the North American F-86 Sabreand Boeing B-47 Stratojet. -

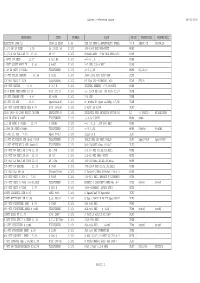

Subject Reference Dbase 09-05-2006

Subject reference dbase 09-05-2006 ONDERWERP TYPE NUMMER BIJZ GROEP TREFWOORD1 TREFWOORD2 ELECTRON 1958.12 1958.12 ELEC Z 46 TEK CX GEVR L,KWANTONETC KUBEL TS-N KERST CX LW,KW,LO 0,5/1 KW LW SEND 2.39 As 33/A1 34 Z 101 100-1000 KHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 0,7/1,4 KW SEND AS 60 10.40 AS 60 Z 101 FRUEHE AUSF 3-24 MHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 1 KWTT KW SEND 11.37 S 521 Bs Z 101 =+/-G 1,5.... MOBS 1 KWTT SHORT WAVE TR 5.36 S 486F Z 101 3-7 UND 2,5-6 MHZ MOBS 1 kW KW SEND S 521Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,2K MOBS G1,2K+/- 10 WTT TELEF SENDER 10.34 S 318H Z 101 1500-3333 KHZ GUSS GEH SCHS 100 WTT SEND S 317H TELEFUNKEN Z 172 RS 31g 100-800METER alt SCHS S317H 100 WTT SENDER 4.33 S 317 H Z 101 UNIVERS SENDER 377-3000KHZ MOBS 15 W EINK SEND EMPF 10.35 Stat 272 B Z 101 +/- 15 W SE 469 SE 5285 F1/37 TRSE 15 WTT KARREN STN 4.40 SE 469A Z 101 3-5 MHZ TRSE 15 WTT KW STN 10.35 Spez804/445 Z 101 S= 804Bs E= Spez 445dBg 3-7,5M TRSE 150 WTT LANGW SENDE ANL 8.39 Stat 1006aF Z 101 S 427F SA 429F FLFU 1898-1938 40 JAAR RADIO IN NED SWIERSTRA R. Z 143 INLEGVEL VAN SWIERSTA PRIVE'38 LI 40 RADIO!! WILHELMINA 1kW KW SEND S 486F TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-2,5-7,5MHZ MOBS S486 1,5 LW SEND S 366Bs 11.37 S 366Bs Z 101 =+/- G1,5...100-600 KHZ MOBS 1,5kW LW SEND S366Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,5L MOBS S366Bs S366BS 20 WTT FL STN 3.35 Spez 378mF Z 101 TELEF D B FLFU 20 WTT FLUGZEUG STN Spez 378nF TELEFUNKEN Z 172 URALT ANL LW FEST FREQU FLFU Spez378nF Spez378NF 20 WTT MITTELWELL GER Stat901 TELEFUNKEN Z 172 500-1500KHZ Stat 901A/F FLFU 200 WTT KW SEND AS 1008 11.39 AS 1008 Z 101 2,5-10 MHZ A1,A2,A3,HELL -

Battletech Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade

TM In 3055, a new breed of Inner Sphere BattleMech started rolling off assembling lines—’Mechs specifically designed to counter the Clan invasion—at the same time that second- line Clan ’Mechs began to appear. By 3067 those design have become a staple of the modern battlefield, giving rise to notable MechWarriors and new variants, while the demands of the ever-popular Solaris VII Games have resulted in a plethora of new dueling ’Mechs designed using prototype technology. Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade presents the Solaris VII ’Mechs built using prototype technologies. Upgraded in appearance and technology, the designs first presented in the Solaris VII box set and Solaris: The Reaches are now back in print, along with several new Solaris VII designs. In addition to the upgraded appearance of selected Clan designs, all the art work for Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade is new, providing fresh illustrations of now- classic Inner Sphere BattleMechs and Clan OmniFighters. The ’Mechs in the Solaris VII BattleMechs section are constructed using select equipment found in Tactical Operations. To use those designs, players will need that book. STAR LEAGUE ERA CLAN INVASION ERA JIHAD ERA ® SUCCESSION WARS ERA CIVIL WAR ERA DARK AGE ERA ©2011 The Topps Company Inc. All Rights Reserved. BattleTech Technical Readout: 3055 Upgrade, Classic BattleTech, BattleTech, BattleMech, and ’Mech are registered trademarks and/or trademarks of WWW.CATALYSTGAMELABS.COM The Topps Company Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Catalyst Game Labs and the Catalyst Game Labs logo are trademarks of InMediaRes Productions, LLC. Printed in the U.S.A. -

Weapons Pack

Weapons Pack for Strike Fighters: Project 1 Wings Over Vietnam Wings Over Europe 03 Jul 2006 ________________________________________________________________________ Rob "Bunyap" McCray [email protected] www.bunyap2w1.com Overview This project is designed to provide a hassle free way of obtaining every 3rd party released weapon and gun. It will be updated after every aircraft release to include the newly created ordnance, gun types, and fuel tanks. All data is checked and verified by experts to provide the most realistic weapons effects and performance possible. The Weapons Pack is compatible with Strike Fighters: Project 1, Wings Over Vietnam, and Wings Over Europe. This version of the Weapons Pack has been re-designed with a far superior system for nation and date assignments than previous versions. Modified aircraft data must be used to take advantage of this. Instructions for installing this data and modifying aircraft that are not included are provided. Some other enhancements include functional targeting pods, guidance for laser, EO, IIR, and GPS guided bombs, better missile guidance, functional EO/IR guided missiles, and functional weapon availability dates. Effects created by Deuces or based on his work are included covering the range of weapons currently available. These include: Bomb explosion effects of various sizes. Cluster Bomb explosion effects. Rocket Launcher effects. Missile and Rocket motor effects. Smoke trails. White Phosphorus explosion effects. Colored smoke effects for WP rockets. Leaflet bomb effects. Chaff and flare effects. White Phosphorus smoke for Anti-radiation missiles. Inert bomb and rocket effects. Spotting charge effects for practice bombs. Rocket sub-munition effects. Illumination flare effects. Napalm explosion effects. -

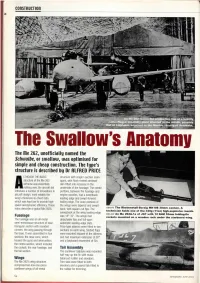

Messerschmitt Me 262B-1A/U1

consTRUCTion Me 262 ieaves the production (ine at a heavjly assembly piant situated in the woods, possibly eim, adjacent to the Munich—Stuttgart Autobahn. The Swallow's Anatomy The me 262, unofficially named the Sclìwalbe, or swallow, mas optimised for simple and cheap construction. The type's structure is described by Dr RLFRED PRICE LTHOUGH THE BASIC structure with single l-section main- Structure of the Me 262 spars, with flush-riveted stressed airframe was essentially skin fitted into recesses in the A nothing new, the aircraft did underside of the fuselage. The centre introduce a number of innovations in portions, between the fuselage and aircraft design, most notably the engine nacelles, had a sweptback wing's thickness-to-chord ratio, leading edge and swept-forward which was kept low to provide high- trailing edge. The outer portions of speed aerodynamic efficiency. These the wings were tapered and swept• notes describe a typical Me 262A. back, with square-cut tips. The ABOVE The Rheìnmetall-Borsig MK108 30mm cannon. A sweepback at the wing leading edge technician hoids one of the 330g (11oz) high-explosive rounds. BELOW An Me 262A-1a of JG7 with 12 R4M 55mm folding-fìn Fuselage was 18° 32'. The wings had rocitets mounted on a wooden racle under the starboard wing. The fuselage was an ali-metal detachable tips and full-span semi-monocoque structure of near- automatic leading-edge slats. triangular section with rounded Frise-type ailerons were fitted in two corners, the wing passing through sections on each wing, Slotted flaps the base. It was assembied in tour were mounted inboard of the ailerons sections: the nose cone, which and had maximum extension of 60° housed the guns and ammunition, and a backward movement of Sin. -

Dornier Do.335 Pfeil Kyushu J7W Shinden Lavochkin La-11 North

Dornier Do.335 Pfeil Kyushu J7W Shinden Lavochkin La-11 North American P-82 Twin Mustang Gloster Meteor F.III Messerschmitt Me.262A-1 Schwalbe Mikoyan-Gurevich Mig-15bis North American F-86A-5 Sabre PILOTING (LIGHT AIRPLANE) TL Vehicle ST/HP Hnd/SR HT Move Lwt. Load SM Occ. DR Range Stall Locations Notes 7 Do.335 Pfeil 100 0/3 9f 3/238 10.5 1.1 +5 1 5 1250 54 g3WrWi [1, 2] 7 J7W Shinden 79 +1/3 9f 3/227 5.8 0.2 +4 1 5 2080 52 g3WrWi [1, 3] 7 Twin Mustang 100 +1/3 10f 2/224 12.9 2.2 +5 2 5 2240 57 2g4WrWi [1, 4] 7 La-11 73 +2/3 10f 4/204 4.4 0.2 +4 1 5 1400 50 g3WrWi [1, 5] Notes: [1] Pilot is protected by DR 30 against attacks from forward and back. [2] Engine-mounted Mk-103 30mm autocannon with 70 rounds of ammunition, two synchronized MG151/20 autocannons (High-Tech, p.133) with 200 rounds of ammunition each. Can carry four SC250 bombs (High-Tech, p.195). [3] Four Type 5 30mm autocannons with 60 rounds of ammunition each. Two Type 97 60kg bombs. [4] Six M2 Browning machine guns (High-Tech, p.133) with 300 rounds of ammunition each. Can mount one of the following: two 2000lb bombs, 4 1000lb bombs, 10 HVAR rockets, a pod with additional eight M2 Brownings and 400 rounds of ammunition for each, or a radar. [5] Three synchronized NS-23 23mm autocannons with 75 rounds of ammunition each. -

The Missiles Work” Technological Dislocations and Military Innovation

THE 12 DREW PER PA S “All the Missiles Work” Technological Dislocations and Military Innovation A Case Study in US Air Force Air-to-Air Armament Post–World War II through Operation Rolling Thunder Steven A. Fino Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Steven L. Kwast, Lieutenant General, Commander and President School of Advanced Air and Space Studies Thomas D. McCarthy, Colonel, Commandant and Dean AIR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIR AND SPACE STUDIES “All the Missiles Work” Technological Dislocations and Military Innovation A Case Study in US Air Force Air-to-Air Armament, Post–World War II through Operation Rolling Thunder Steven A. Fino Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Drew Paper No. 12 Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Belinda L. Bazinet Fino, Steven A., 1974– Copy Editor “All the missiles work” : technological dislocations and mili- Carolyn Burns tary innovation : a case study in US Air Force air-to-air arma- ment, post-World War II through Operation Rolling Thunder / Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations Steven A. Fino, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF. Daniel Armstrong pages cm. — (Drew paper, ISSN 1941-3785 ; no. 12) Composition and Prepress Production ISBN 978-1-58566-248-7 Vivian D. O’Neal 1. Air-to-air rockets—United States—History. 2. Guided Print Preparation and Distribution missiles—United States—History. 3. Airplanes, Military— Diane Clark Armament—United States—History. 4. Airplanes, Military— Armament—Technological innovations. 5. United States. Air Force—Weapons systems—Technological innovations. I. Title. II. Title: Technological dislocations and military innovation, a case study in US Air Force air-to-air armament, post-World War AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE II through Operation Rolling Thunder. -

O Messerschmitt Me 262 Um Novo Paradigma Na Guerra Aérea

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS O MESSERSCHMITT ME 262 UM NOVO PARADIGMA NA GUERRA AÉREA (1944-1945) NORBERTO ANTÓNIO BIGARES DE MELO ALVES MARTINS Tese orientada pelo Professor Doutor António Ventura e co-orientada pelo Professor Doutor José Varandas, especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em HISTÓRIA MILITAR. 2016 «Le vent se lève!...il faut tenter de vivre!» Paul Valéry, Le cimetière marin, 1920. ÍNDICE RESUMO/ABSTRACT 3 PALAVRAS-CHAVE/KEYWORDS 5 AGRADECIMENTOS 6 ABREVIATURAS 7 O SISTEMA DE DESIGNAÇÃO DO RLM 8 A ESTRUTURA OPERACIONAL DA LUFTWAFFE 11 INTRODUÇÃO 12 1. O estado da arte 22 CAPÍTULO I Conceito, forma e produção 27 1. Criação do Me 262 27 2. Interferência de Hitler no desenvolvimento do Me 262 38 3. Produção do Me 262 42 4. Variantes do Me 262 45 CAPÍTULO II A guerra aérea: novas possibilidades 61 1. O Me 262 como caça intercetor 61 2. O Me 262 como caça-bombardeiro 75 3. O Me 262 como caça noturno 83 4. O Me 262 como avião de reconhecimento 85 5. O Me 262 no РОА/ROA (Exército Russo de Libertação) 89 6. Novas táticas 91 1 7. Novo armamento 96 8. O fator humano 100 CAPÍTULO III O legado do Me 262 104 1. Influência na aerodinâmica 104 2. Inovações 107 3. Variantes estrangeiras do Me 262 109 4. Influência do Me 262 em aviões estrangeiros 119 CONCLUSÃO 130 O Me 262 no espaço aéreo: um novo paradigma 132 BIBLIOGRAFIA 136 ANEXOS 144 2 RESUMO A Segunda Guerra Mundial foi, para além de um evento decisivo na transformação do Mundo, palco de imensos desenvolvimentos técnologicos cuja influência se estende até hoje, fazendo parte, inclusive, do dia a dia de milhões de pessoas. -

Bachem-Werke Ba 349 "Natter"

An Illustrated Series on Germany's Experimental Aircraft of World War II David Myhra Bachem-Werke Ba 349 "Natter" David Myhra Schiffer Military History Atglen, PA Book Design by Ian Robertson. Copyright © 1999 by David Myhra. Library of Congress Catalog Number: 99-66304. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any forms or by any means - graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems - without written permission from the copyright holder. "Schiffer," "Schiffer Publishing Ltd. & Design," and the "Design of pen and ink well" are registered trademarks of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. Printed in China. ISBN: 0-7643-1032-1 We are interested in hearing from authors with book ideas on military topics. Published by Schiffer Publishing Ltd. In Europe, Schiffer books are distributed by: 4880 Lower Valley Road Bushwood Books Atglen, PA 19310 USA 6 Marksbury Road Phone:(610)593-1777 Kew Gardens FAX: (610) 593-2002 Surrey TW9 4JF E-mail: [email protected] England Visit our web site at: www.schifferbooks.com Phone: 44 (0)208 392-8585 Please write for a free catalog. FAX: 44 (0)208 392-9876 This book may be purchased from the publisher. E-mail: [email protected]. Please include $3.95 postage. Try your bookstore first. Try your bookstore first. Bachem Ba 349 The Bachem Ba 349 [BP-20] "Natter"—meaning ers by Hermann Göring. Galland had been pretty much 509A2 bi-fuel liquid rocket engine producing 3,307 viper or snake—was, near war's end, one of the des- without a job until Hitler allowed to form a fighter group pounds [1,500 kilograms] thrust. -

Recon Inside 2016-2017 Dues

June 2017 Recon Inside IPMS Nationals 2017 - July 26-29, 2017, LaVista Recon 1 Conference Center, La Vista, NE Contact, Scot Hackney at 402-598-6114 In Box Review 2-3 Patcon 2017 – Sept 17, 2017, Hudson Elks Hall From the Bridge 4-6 99 Park Street Hudson, MA Contact, [email protected] or 978-706-1211 Up Scope 7 Armorcon 2017 – Sept 22-23, 2017, Crowne Plaza Hobby Shops 8-9 Danbury 18 old Ridgeway Road Danbury, CT Contact, Bill Schmidt [email protected] In Range 9 or 203-735-9014 By Laws Voting 10 Ganitecon 2017 – Oct 15, 2017, Falls Event Center 21 Front Street Manchester, NH Contact, Mac Johnston 603-359-0595 2016-2017 Dues If you have not already done so, please renew RIMA Expo 2017 – Oct 22, 2017, Burrillville your dues for the coming 2016-2017 membership Middle School, Harrisville, RI Contact, year. Dues are still $10. [email protected] or Neil DeConte at 401- 477-4145 Please remit your dues to John Nickerson at the meeting or send it to him at 18 Stone Street, Baycon 2017 - Nov 12, 2017, Elks Hall 326 Middleboro, MA 02346 . Farnum Pike Smithfield, RI Contact, Robert Magina 508-695-7754 or [email protected] Don't forget to ask for the Family Membership if you have sons or daughters as members in the club as well. Page 1 Page 2 In the Box Review Academy Me262-1/2 “Last Ace” Special Edition 1/72 scale kit no. 12542 By John Nickerson The kit is not new but the boxing is. -

NW68 Rulebook

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Timeline 4 2.0 Components 6 2.1 The Map 6 2.2 The Counters 6 2.3 Unit Types 6 2.3.1 Commanding Officers 7 2.3.2 Infantry 8 2.3.2.1 Weapons 8 2.3.3 Armored Units 9 2.3.3.1 Tanks 9 2.3.3.2 APCs 9 2.3.3.3 Recon 10 2.3.3.4 SP Artillery 10 2.3.3.5 SP Anti-Aircraft 10 2.3.4 Air Units 11 2.3.4.1 Helicopters 11 2.3.4.2 Airplanes 12 2.4 Markers 13 2.4.1 Off-Board Artillery 13 2.5 Formations 14 3.0 Course Of Play 14 3.1 Actions Phase 14 3.2 Formation Impulse 15 3.3 Movement 15 3.3.1 Group Movement 15 3.3.2 Stacking 15 3.4 Events 15 3.5 Cleanup Phase 16 4.0 Terrain 16 4.1 Line Of Sight 16 4.2 Concealment 17 4.3 Control 17 5.0 Combat 17 5.1 Group Fire 18 5.2 Opportunity Fire 18 5.3 Moving Fire 18 5.4 Assault 18 5.5 Combat Results 19 6.0 Order Of Battle 19 7.0 Credits 19 8.0 Scenarios 21 Without water, food and electricity, the population's morale declines rapidly 1.0 TIMELINE while the army without a leader and no communications falls into disarray. Germany collapses. Radiation levels skyrocket. Armed guards are posted 1943 - Following the disaster at Stalingrad, a small Anti-Hitler group is on all major access routes into the former German territory and all land formed in Berlin around Oberstleutnant Claus von Stauffenberg. -

Focke-Wulf Fw 190

Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Fw 190 Fw 190As of Jagdgeschwader 54. Type Fighter Manufacturer Primarily Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau AG, but also Ago, Arado, Fieseler, Mimetall, Norddeutsche Dorner and others Designed by Kurt Tank Maiden flight 1 June 1939 Introduced August 1941 Retired 1945 (Luftwaffe) Primary users Luftwaffe Hungarian Air Force Turkish Air Force Romanian Air Force Produced 1941-1945 Number built Over 20,000 Variants Ta 152 The Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Würger ("shrike"), often called Butcher-bird, was a single-seat, single- engine fighter aircraft of Germany's Luftwaffe, and one of the best fighters of its generation. Used extensively during the Second World War, over 20,000 were manufactured, including around 6,000 fighter-bomber models. Production ran from 1941 to the end of hostilities, during which time the aircraft was continually updated. Its final incarnations retained qualitative parity with Allied fighter planes, although Fw 190s lagged far behind in production numbers. The Fw 190 was well liked by its pilots, and widely regarded as superior to the front line Supermarine Spitfire Mk V on its combat debut in 1941. Compared to the Bf 109, the Fw 190 was a "workhorse," 1 employed in and proved suitable for a wide variety of roles, including ground attack, long-range bomber escort, night-fighter and (especially in the "D" version) high-altitude interceptor. Early development In autumn 1937, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) or Reich Air Ministry asked various designers for a new fighter to fight alongside the Messerschmitt Bf 109, Germany's front line fighter. Although the Bf 109 was at that point an extremely competitive fighter, the RLM was worried that future foreign designs might outclass it and wanted to have new aircraft under development just in case.[1] Kurt Tank responded with a number of designs, most incorporating liquid-cooled inline engines.