Coproduction Challenges in the Context of Changing Rural Livelihoods *Ruxandra Popovici1, Katy E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geosites and Geotouristic Attractions Proposed for the Project Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua, Peru

Geoheritage (2018) 10:707–729 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-018-0307-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Geosites and Geotouristic Attractions Proposed for the Project Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua, Peru Andrzej Gałaś1 & Andrzej Paulo1 & Krzysztof Gaidzik2,3 & Bilberto Zavala4 & Tomasz Kalicki5 & Danitza Churata4 & Slávka Gałaś1 & Jersey Mariño4 Received: 15 July 2016 /Accepted: 18 May 2018 /Published online: 7 June 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract The Colca Canyon (Central Andes, Southern Peru), about 100 km long and 1–3 km deep, forms a magnificent cross section of the Earth’s crust giving insight into mutual relations between lithostratigraphical units, and allowing relatively easy interpretation of the fascinating geological history written in the rocky beds and relief. Current activity of tectonic processes related to the subduction of the Nazca plate beneath the South American Plate exposed the geological heritage within study area. Well- developed tectonic structures present high scientific values. The volcanic landforms in the Valley of the Volcanoes and around the Colca Canyon include lava flows, scoria cones and small lava domes. They represent natural phenomena which gained recognition among tourists, scientists and local people. Studies performed by the Polish Scientific Expedition to Peru since 2003 recognized in area of Colca Canyon and Valley of the Volcanoes high geodiversity, potential for geoturism but also requirements for protectection. The idea of creating geopark gained recently the approval of regional and local authorities with support from the local National Geological Survey (INGEMMET). The Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua would strengthen the relatively poor system of the protected areas in the Arequipa department, increasing the touristic attractiveness and determine constraints for sustained regional development. -

UGEL ESPINAR O Cerro Salla Lori

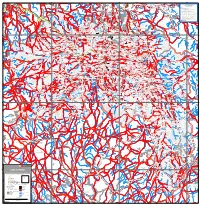

-71 .67 -71 .34 -71 VELILLE 617316 240494 C Soromisa Callejon Pampa 112885 e Consapata ") sa $+ Chaychapampa r a ome o 4 *# 652213 ") ro h c or 613309 *# y 0 400 o S 0 (! 210738 M c 516931 a Cerr lu 0 C Pukañan Cerro Silluta i Cerros Occorotoñe n a 0 e sa a o im C r 539319 Rosaspata # y C r r Huarcachapi / Qquellabamba a * Cerr c o o # o o Celopinco u r %, LAGO Huallataccota * Cerro Incacancha c C c Q a c a er Cerro Quirma Q 119397 *# 222362 a a Q c o p p Cerro Huacot 530275 Q a UGEL CHUMBIVILCAS l e d n C u o LANGUI l c d d r l I M m A Q Carta Educativa 2018 l i a a r a . a is Hilatunga d a C . o i n o a o CHECCA p i u *# C F C C . a h a LAYO . p r 617660 z a C d u a S L s R Sausaya u a u c e i p h r R o Q u u y c e a a c a l Q i Elaborada por la Unidad de Estadística del r e r u A i a Ccochapata y o c l n t r Cerro Mauro Moa 110101 Cerro Oquesupa n a Taypitunga t u r h i t . c am ") Exaltacion o o i Q i P a C a n d r a m 4000 e ta P 527487 Campo Villa c o a h . -

Comprender La Agricultura En Los Andes Peruanos: Religión En La Comunidad De Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa)

Comprender la agricultura en los Andes Peruanos: Religión en la comunidad de Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/article Authors Sánchez Dávila, Mario Elmer Publisher Centro de Estudios Antropológicos Luis Eduardo Valcárcel Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess Download date 02/10/2021 15:30:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/622562 Comprender la agricultura en los Andes Peruanos: Religión en la comunidad de Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) Understanding agriculture in the Peruvian Andes: Religión in the community of Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) MARIO E. SÁNCHEZ DÁVILA1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP) Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) [email protected] Recibido: 04 de julio de 2017 Aceptado: 01 de septiembre de 2017 Resumen Este artículo analiza la agricultura en el mundo Andino a través del caso la comunidad de Yanque, distrito de la provincia de Caylloma, departamento de Arequipa (Perú). La agricultura es su principal actividad social debido a la importancia colectiva no sólo de sus manifestaciones económicas y políticas, sino también religiosas. Por eso, este artículo se enfoca en las expresiones religiosas más visibles: el sincretismo católico-quechua y la fiesta laboral ritualizada del Yarqa Aspiy. Palabras clave: andes, agricultura, religión, Perú Abstract This paper analyzes agriculture in the Andean world through the case of the community of Yanque, district of Caylloma province, department of Arequipa (Perú). Agriculture comes to have an organizing force in this community not only for its economic and political effects, but also for its religious dimensions. For this reason, this paper focuses on one of the community’s most visible religious expressions: the Yarqa Aspiy, describing the ways in which this festival ritualizes labor in performances of Catholic-Quechua syncretism. -

INDIGENOUS LIFE PROJECTS and EXTRACTIVISM Ethnographies from South America Edited by CECILIE VINDAL ØDEGAARD and JUAN JAVIER RIVERA ANDÍA

INDIGENOUS LIFE PROJECTS AND EXTRACTIVISM Ethnographies from South America Edited by CECILIE VINDAL ØDEGAARD and JUAN JAVIER RIVERA ANDÍA APPROACHES TO SOCIAL INEQUALITY AND DIFFERENCE Approaches to Social Inequality and Difference Series Editors Edvard Hviding University of Bergen Bergen, Norway Synnøve Bendixsen University of Bergen Bergen, Norway The book series contributes a wealth of new perspectives aiming to denaturalize ongoing social, economic and cultural trends such as the processes of ‘crimigration’ and racialization, fast-growing social-economic inequalities, depoliticization or technologization of policy, and simultaneously a politicization of difference. By treating naturalization simultaneously as a phenomenon in the world, and as a rudimentary analytical concept for further development and theoretical diversification, we identify a shared point of departure for all volumes in this series, in a search to analyze how difference is produced, governed and reconfigured in a rapidly changing world. By theorizing rich, globally comparative ethnographic materials on how racial/cultural/civilization differences are currently specified and naturalized, the series will throw new light on crucial links between differences, whether biologized and culturalized, and various forms of ‘social inequality’ that are produced in contemporary global social and political formations. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14775 Cecilie Vindal Ødegaard Juan Javier Rivera Andía Editors Indigenous Life Projects and Extractivism Ethnographies from South America Editors Cecilie Vindal Ødegaard Juan Javier Rivera Andía University of Bergen Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Bergen, Norway Barcelona, Spain Approaches to Social Inequality and Difference ISBN 978-3-319-93434-1 ISBN 978-3-319-93435-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93435-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018954928 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. -

Final Project Report

STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES FOR DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND INCREASING RESILIENCE IN COMMUNITIES OF CAYLLOMA, AREQUIPA. FINAL PROJECT REPORT OCTOBER 2018 – DECEMBER 2019 GENERAL PROJECT INFORMATION STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES FOR DISASTER RISK Project Title REDUCTION AND INCREASING RESILIENCE IN COMMUNITIES OF CAYLLOMA, AREQUIPA. Award number 72OFDA18GR00319 Registration number REQ-OFDA-18-000751 Start date October 01, 2018 Duration 15 months Country / region: Peru / department of Arequipa, province of Caylloma. Reported period: October 2018 – December 2019 Date of report: February 21, 2020 Adventist Development and Relief Agency International - ADRA INTERNATIONAL Report for: Debra Olson, Program Manager, Program Implementation Unit. Nestor Mogollon, Director of Monitoring and Evaluation. Adventist Development and Relief Agency Perú – ADRA Perú Víctor Huamán, Project Manager. Report by: cell phone: 51 - 997 555 483 - email: [email protected] Erick Quispe, Project Field Coordinator. cell phone: 51 - 966 315 430 - email: [email protected] REPORTE ANUAL: OCTUBRE 2018 – SETIEMBRE 2019 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since 2016, the Sabancaya volcano has registered permanent eruptive activity with gas, ash and earthquake emissions, which together with other natural events such as earthquakes, frost, intense rains and landslides interrupt local development and affect thousands of people in the Caylloma province. For this reason, the project aimed to integrate disaster risk management into institutional management tools of local governments in the Caylloma Province, with the participation of the population and collaboration at the regional and national levels. The project " Allichakusun ante desastres" (“Preparing ourselves for disasters”) began in October 2018 and ended in December 2019. It executed 100% of the financing received from USAID, also achieving an income of S/. -

Challenges and Opportunities of International University Partnerships to Support Water Management

Issue 171 December 2020 2019 1966 Challenges and Opportunities of International University Partnerships to Support Water Management A publication of the Universities Council on Water Resources with support from Southern Illinois University Carbondale JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY WATER RESEARCH & EDUCATION Universities Council on Water Resources 1231 Lincoln Drive, Mail Code 4526 Southern Illinois University Carbondale, IL 62901 Telephone: (618) 536-7571 www.ucowr.org CO-EDITORS Karl W. J. Williard Jackie F. Crim Southern Illinois University Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois Carbondale, Illinois [email protected] [email protected] SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORS Laura C. Bowling Katy E. Mazer John E. McCray Professor, Dept. of Agronomy Sustainable Water Management Coordinator Professor Co-Director, Natural Resources & Arequipa Nexus Institute Civil and Environmental Engineering Dept. Environmental Sciences Program Purdue University Hydrologic Science & Engineering Program Purdue University [email protected] Colorado School of Mines [email protected] [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS Kofi Akamani Natalie Carroll Mae Davenport Gurpreet Kaur Policy and Human Dimensions Education Policy and Human Dimensions Agricultural Water and Nutrient Management Southern Illinois University Purdue University University of Minnesota Mississippi State University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Prem B. Parajuli Gurbir Singh Kevin Wagner Engineering and Modeling Agriculture and Watershed Management Water Quality and Watershed -

Semi‐Annual Report

STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES FOR DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND INCREASING RESILIENCE IN COMMUNITIES OF CAYLLOMA, AREQUIPA. SEMI‐ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 2018 – MARCH 2019 GENERAL PROJECT INFORMATION STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES FOR DISASTER RISK Project Title REDUCTION AND INCREASING RESILIENCE IN COMMUNITIES OF CAYLLOMA, AREQUIPA. Award number 72OFDA18GR00319 Registration number REQ-OFDA-18-000751 Start date September 01, 2018 Duration 12 months Country / region: Peru / department of Arequipa, province of Caylloma Reported period: October 2018 - March 2019 Date of report: April 24, 2019. Adventist Development and Relief Agency International - ADRA INTERNACIONAL Report for: Debra Olson, Program Manager, Program Implementation Unit. Nestor Mogollon, Director of Monitoring and Evaluation. Adventist Development and Relief Agency Perú – ADRA Perú Víctor Huamán, project manager. Report by: cell phone: 51-997 555 483 - email: [email protected] Erick Quispe, local coordinator. cell phone: 51-966 315 430 - email: [email protected] SEMI‐ANNUAL REPORT: OCTOBER, 2018 – MARCH, 2019 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The province of Caylloma has been suffering from natural disasters that disrupt local development and affect several thousand people, such as earthquakes, frequent heavy rains, floods, mudslides and rock falls; and additionally, since 2016 the Sabancaya volcano registers permanent eruptive activity that alerts the local community in Caylloma. In this scenario, the objective of the project is to integrate disaster risk management into institutional management tools of local governments, with the participation of the population and collaboration at the regional and national levels. In the first semester of implementation, the project in sector 1 reached 60% of beneficiaries in subsector 1; and in sector 2 it reached 80.2% of beneficiaries for subsector 1, and 152% of beneficiaries for subsector 2, and subsector 3 considers only products for this report. -

The Ethno-Politics of Water Security

The Ethno-politics of Water Security: Contestations of ethnicity and gender in strategies to control water in the Andes of Peru Juana Rosa Vera Delgado Thesis committee Thesis supervisors Prof. dr. L.F. Vincent Professor of Irrigation and Water Engineering Wageningen University Prof. dr. E.B. Zoomers Professor of International Development Studies Utrecht University Thesis co-supervisor Dr. ir. M.Z. Zwarteveen Assistant professor, Irrigation and Water Engineering Group Wageningen University Other members Prof. dr. ir. J.D. van der Ploeg, Wageningen University Dr. ir. R. Ahlers, UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, Delft Dr. ir. G. van der Haar, Wageningen University Dr. D. Roth, Wageningen University This research was conducted under the auspices of the Wageningen School of Social Sciences (WASS) The Ethno-politics of Water Security: Contestations of ethnicity and gender in strategies to control water in the Andes of Peru Juana Rosa Vera Delgado Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Friday 23 December 2011 at 1.30 p.m. in the Aula. Juana Rosa Vera Delgado The Ethno-politics of Water Security: Contestations of ethnicity and gender in strategies to control water in the Andes of Peru. 257 pages Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2011) With references, with summaries in Dutch, English and Spanish ISBN: 978-94-6173-104-3 This research described in this thesis was financed by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, NWO). -

Caylloma, Arequipa) Understanding Agriculture in Peruvian Andes: Economy and Politics in the Community of Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) MARIO Sánchez*

Revista Antropologías del Sur Año 4 N°7 2017 Págs. 235 - 256 | 235 COMPRENDER LA AGRICULTURA EN LOS ANDES PERUANOS: ECONOMÍA Y POLÍTICA EN LA COMUNIDAD DE YANQUE (CAYLLOMA, AREQUIPA) Understanding Agriculture in Peruvian Andes: Economy and Politics in the Community of Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) MARIO SÁNCHEZ* Fecha de recepción: 28 de diciembre de 2016 – Fecha de aprobación: 25 de abril de 2017 Resumen Este artículo analiza la agricultura en el mundo andino a través del caso de la comunidad de Yanque, distrito de la provincia de Caylloma, departamento de Arequipa (Perú). La agricultura es su principal actividad social debido a la vital importancia colectiva de sus dimensiones económicas y políticas, que muestran cómo Yanque es una comunidad andina que, en el siglo XXI, continúa preservando la tradición de sus herencias culturales mientras se encuentra inserta en modernos cambios sociales que conllevan los dinámicos procesos de interrelación con sociedades urbanas y globales capitalistas. Palabras clave: Andes, Agricultura, Economía, Política, Perú Abstract This paper analyzes agriculture in the andean world through the case of the community of Yanque, district of Caylloma province, department of Arequipa (Peru). Agriculture is the main social activity because of the vital collective importance of its economic and politics dimensions, that show how Yanque is an Andean community that, in the 21st century, continues to preserve the tradition of its cultural heritages while it is inserted in modern social changes that entail the dynamic processes of interrelation with urban and global capitalist societies. Keywords: Andes, Agriculture, Economy, Politics, Peru * Doctorante en Antropología con mención en Estudios Andinos, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP). -

Cultivating What Is Ours Local Agro-Food Heritage As a Development Strategy in the Peruvian Andes

Cultivating what is ours Local agro-food heritage as a development strategy in the Peruvian Andes Simon Bidwell A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2020 Abstract The Peruvian Andes has long been portrayed as a space of poverty and marginalisation, but more recently Andean places have been reinterpreted as reservoirs of valuable patrimonio agroalimentario (agro-food heritage). Amidst global interest in food provenance and Peru’s gastronomic ‘boom’, Andean people and places have connected with different networks that value the geographical, ecological and social origins of food. This thesis explores the meaning of these changes by combining a discourse genealogy with local case studies. I first trace the emergence of interconnecting discourses of territorial development with identity and local agro-food heritage in Latin America. I explore how these discourses bring together diverse actors and agendas through arguments that collective action to revalue local agro-food heritage can offer equitable economic gains while conserving biocultural diversity, a theoretical dynamic that I term the ‘virtuous circle of products with identity.’ These promises frame in-depth case studies of Cabanaconde and Tuti, two rural localities in the southern Peruvian Andes where a range of development initiatives based on local agro-food heritage were undertaken from around the mid-2000s. The case studies combine evaluation of the economic, social, cultural and environmental impacts of the initiatives, with ethnographic perspectives that look at them through the lens of local livelihoods. The partial successes and multiple setbacks of the initiatives highlight the tensions between economic impact, social equity and biocultural diversity while underlining the limitations of existing markets to value the rich connections between place and food in the Andes. -

A RETURN to the VILLAGE Community Ethnographies and the Study of Andean Culture in Retrospective Edited by Francisco Ferreira with Billie Jean Isbell

A RETURN TO THE VILLAGE Community ethnographies and the study of Andean culture in retrospective edited by Francisco Ferreira with Billie Jean Isbell A Return to the Village: Community Ethnographies and the Study of Andean Culture in Retrospective edited by Francisco Ferreira with Billie Jean Isbell © Institute of Latin American Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2016 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-908857-24-8 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-908857-84-2 (PDF) Institute of Latin American Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House London WC1E 7HU Telephone: 020 7862 8844 Email: [email protected] Web: http://ilas.sas.ac.uk Contents List of illustrations v List of acronyms and abbreviations ix Notes on contributors xi Acknowledgments xvii Introduction: Community ethnographies and the study of Andean culture 1 Francisco Ferreira 1. Reflections on fieldwork in Chuschi 45 Billie Jean Isbell (in collaboration with Marino Barrios Micuylla) 2. Losing my heart 69 Catherine J. Allen 3. Deadly waters, decades later 93 Peter Gose 4. Yanque Urinsaya: ethnography of an Andean community (a tribute to Billie Jean Isbell) 125 Carmen Escalante and Ricardo Valderrama 5. Recordkeeping: ethnography and the uncertainty of contemporary community studies 149 Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld 6. Long lines of continuity: field ethnohistory and customary conservation in the Sierra de Lima 169 Frank Salomon 7. Avoiding ‘community studies’: the historical turn in Bolivian and South Andean anthropology 199 Tristan Platt 8. In love with comunidades 233 Enrique Mayer References 265 Index 295 List of illustrations Figure 0.1 The peasant community of Taulli (Ayacucho, Peru). -

Project on “Intellectual Property and Gastronomic Tourism in Peru

Project on “Intellectual property and gastronomic tourism in Peru and other developing countries: Promoting the development of gastronomic tourism through intellectual property”: SCOPING STUDY January 2020 Consultant: Carmen Julia García Torres 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter I: Background 7 Chapter II: Justification 9 Chapter III: Analysis of Peruvian gastronomy 13 3.1 The environment and products 15 3.2 Economic analysis 21 3.3 Reputation and influence 27 3.4 Potential challenges 38 Chapter IV: Analysis of the study’ geographical focus 43 4.1 Selection criteria 43 4.2 Lambayeque 45 4.3 Lima 54 4.4 Arequipa 66 4.5 Tacna 74 4.6 Cuzco 81 4.7 Loreto 90 Chapter V: Analysis of regional culinary traditions 98 5.1 Lambayeque 98 5.2 Lima 108 5.3 Arequipa 119 5.4 Tacna 128 5.5 Cuzco 140 5.6 Loreto 149 Chapter VI: Round table 165 6.1 Onion 166 6.2 Garlic 169 6.3 Ají chili peppers 169 Bibliography 173 Acronyms 177 Annexes: Annex 1: List of Peruvian culinary traditions Annex 2: Fact sheets and questionnaires 3 Annex 3: List of interviewees Annex 4: Food market directory Annex 5: Peruvian restaurants abroad 4 INTRODUCTION Peru has been recognized as the best culinary destination in the world for the eighth consecutive year by the World Travel Awards1, strengthening the country’s association with gastronomy in the minds of Peruvians and foreigners alike. Over the past ten years, Peruvian cuisine has not only gained international renown and recognition, but has become a unifying force, a catalyst for social cohesion and a source of pride, bolstering Peruvians’ national identity.