Terminal Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyber Crime Cell Online Complaint Rajasthan

Cyber Crime Cell Online Complaint Rajasthan Apheliotropic and tardiest Isidore disgavelled her concordance circumcise while Clinton hating some overspreadingdorado bafflingly. Enoch Ephrem taper accusing her fleet rhapsodically. alarmedly and Expansible hyphenate andhomonymously. procryptic Gershon attaints while By claiming in the offending email address to be the cell online complaint rajasthan cyber crime cell gurgaon police 33000 forms received online for admission in RU constituent colleges. Cyber Crime Complaint with cyber cell at police online. The cops said we got a complaint about Rs3 lakh being withdrawn from an ATMs. Cyber crime rajasthan UTU Local 426. Circle Addresses Grievance Cell E-mail Address Telephone Nos. The crime cells other crimes you can visit their. 3 causes of cyber attacks Making it bare for cyber criminals CybSafe. Now you can endorse such matters at 100 209 679 this flavor the Indian cyber crime toll and number and report online frauds. Gujarat police on management, trick in this means that you are opening up with the person at anytime make your personal information. Top 5 Popular Cybercrimes How You Can Easily outweigh Them. Cyber Crime Helpline gives you an incredible virtual platform to overnight your Computer Crime Cyber Crime e- Crime Social Media App Frauds Online Financial. Customer Care Types Of Settlement Processes In Other CountriesFAQ'sNames Of. Uttar Pradesh Delhi Haryana Maharashtra Bihar Rajasthan Madhya Pradesh. Cyber Crime Helpline Apps on Google Play. Cyber criminals are further transaction can include, crime cell online complaint rajasthan cyber criminals from the url of. Did the cyber complaint both offline and email or it is not guess and commonwealth legislation and. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

Combating Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia

CONTENTS COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA Regional Synthesis Paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal APRIL 2003 This book was prepared by staff and consultants of the Asian Development Bank. The analyses and assessments contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Directors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this book and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. i CONTENTS CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS vii FOREWORD xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 UNDERSTANDING TRAFFICKING 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Defining Trafficking: The Debates 9 2.3 Nature and Extent of Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia 18 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis 20 2.5 Conclusions 36 3 DYNAMICS OF TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA 39 3.1 Introduction 39 3.2 Links between Trafficking and Migration 40 3.3 Supply 43 3.4 Migration 63 3.5 Demand 67 3.6 Impacts of Trafficking 70 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS 73 4.1 Conceptual and Legal Frameworks 73 4.2 Crosscutting Issues 74 4.3 International Commitments 77 4.4 Regional and Subregional Initiatives 81 4.5 Bangladesh 86 4.6 India 97 4.7 Nepal 108 iii COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN 5APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING TRAFFICKING 119 5.1 Stakeholders 119 5.2 Key Government Stakeholders 120 5.3 NGO Stakeholders and Networks of NGOs 128 5.4 Other Stakeholders 129 5.5 Antitrafficking Programs 132 5.6 Overall Findings 168 5.7 -

The Indian Police Journal Vol

Vol. 63 No. 2-3 ISSN 0537-2429 April-September, 2016 The Indian Police Journal Vol. 63 • No. 2-3 • April-Septermber, 2016 BOARD OF REVIEWERS 1. Shri R.K. Raghavan, IPS(Retd.) 13. Prof. Ajay Kumar Jain Former Director, CBI B-1, Scholar Building, Management Development Institute, Mehrauli Road, 2. Shri. P.M. Nair Sukrali Chair Prof. TISS, Mumbai 14. Shri Balwinder Singh 3. Shri Vijay Raghawan Former Special Director, CBI Prof. TISS, Mumbai Former Secretary, CVC 4. Shri N. Ramachandran 15. Shri Nand Kumar Saravade President, Indian Police Foundation. CEO, Data Security Council of India New Delhi-110017 16. Shri M.L. Sharma 5. Prof. (Dr.) Arvind Verma Former Director, CBI Dept. of Criminal Justice, Indiana University, 17. Shri S. Balaji Bloomington, IN 47405 USA Former Spl. DG, NIA 6. Dr. Trinath Mishra, IPS(Retd.) 18. Prof. N. Bala Krishnan Ex. Director, CBI Hony. Professor Ex. DG, CRPF, Ex. DG, CISF Super Computer Education Research Centre, Indian Institute of Science, 7. Prof. V.S. Mani Bengaluru Former Prof. JNU 19. Dr. Lalji Singh 8. Shri Rakesh Jaruhar MD, Genome Foundation, Former Spl. DG, CRPF Hyderabad-500003 20. Shri R.C. Arora 9. Shri Salim Ali DG(Retd.) Former Director (R&D), Former Spl. Director, CBI BPR&D 10. Shri Sanjay Singh, IPS 21. Prof. Upneet Lalli IGP-I, CID, West Bengal Dy. Director, RICA, Chandigarh 11. Dr. K.P.C. Gandhi 22. Prof. (Retd.) B.K. Nagla Director of AP Forensic Science Labs Former Professor 12. Dr. J.R. Gaur, 23 Dr. A.K. Saxena Former Director, FSL, Shimla (H.P.) Former Prof. -

Child Trafficking in India

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Human Trafficking 2013 Trafficking at the University of Nebraska 10-2013 Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah Abdelaziz Helwan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/humtrafcon5 Abdelaziz, Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah, "Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India" (2013). Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking 2013. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/humtrafcon5/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking at the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking 2013 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah Abdelaziz This article reviews the current research on domestic trafficking of children in India. Child trafficking in India is a highly visible reality. Children are being sold for sexual and labor exploitation, adoption, and organ harvesting. The article also analyzes the laws and interventions that provide protection and assistance to trafficked children. There is no comprehensive legislation that covers all forms of exploitation. Interven- tions programs tend to focus exclusively on sex trafficking and to give higher priority to rehabilitation than to prevention. Innovative projects are at a nascent stage. Keywords: human trafficking, child trafficking, child prostitution, child labor, child abuse Human trafficking is based on the objectification of a human life and the treat- ment of that life as a commodity to be traded in the economic market. -

Compendium of Best Practices on Anti Human Trafficking

Government of India COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS Acknowledgments ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ms. Ashita Mittal, Deputy Representative, UNODC, Regional Office for South Asia The Working Group of Project IND/ S16: Dr. Geeta Sekhon, Project Coordinator Ms. Swasti Rana, Project Associate Mr. Varghese John, Admin/ Finance Assistant UNODC is grateful to the team of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi for compiling this document: Ms. Bharti Ali, Co-Director Ms. Geeta Menon, Consultant UNODC acknowledges the support of: Dr. P M Nair, IPS Mr. K Koshy, Director General, Bureau of Police Research and Development Ms. Manjula Krishnan, Economic Advisor, Ministry of Women and Child Development Mr. NS Kalsi, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs Ms. Sumita Mukherjee, Director, Ministry of Home Affairs All contributors whose names are mentioned in the list appended IX COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS © UNODC, 2008 Year of Publication: 2008 A publication of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Office for South Asia EP 16/17, Chandragupta Marg Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 110 021 www.unodc.org/india Disclaimer This Compendium has been compiled by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights for Project IND/S16 of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for South Asia. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily represent the official policy of the Government of India or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The designations used do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, frontiers or boundaries. -

A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003

NHRC - UNIFEM - ISS Project A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003 Coordinator Sankar Sen Principal Investigator - Researcher P.M. Nair IPS Volume I Institute of Social Sciences National Human Rights Commission UNIFEM New Delhi New Delhi New Delhi Final Report of Action Research on Trafficking in Women and Children VOLUME – 1 Sl. No. Title Page Reference i. Contents i ii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Justice Dr. A.S. Anand, Chairperson, NHRC) iii-iv iii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Mrs. Justice Sujata V. Manohar) v-vi iv. Foreword (by Ms. Chandani Joshi (Regional Programme Director, vii-viii UNIFEM (SARO) ) v. Preface (by Dr. George Mathew, ISS) ix-x vi. Acknowledgements (by Mr. Sankar Sen, ISS) xi-xii vii. From the Researcher’s Desk (by Mr. P.M. Nair, NHRC Nodal Officer) xii-xiv Chapter Title Page No. Reference 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Review of Literature 7-32 3. Methodology 33-39 4. Profile of the study area 40-80 5. Survivors (Rescued from CSE) 81-98 6. Victims in CSE 99-113 7. Clientele 114-121 8. Brothel owners 122-138 9. Traffickers 139-158 10. Rescued children trafficked for labour and other exploitation 159-170 11. Migration and trafficking 171-185 12. Tourism and trafficking 186-193 13. Culturally sanctioned practices and trafficking 194-202 14. Missing persons versus trafficking 203-217 15. Mind of the Survivor: Psychosocial impacts and interventions for the survivor of trafficking 218-231 16. The Legal Framework 232-246 17. The Status of Law-Enforcement 247-263 18. The Response of Police Officials 264-281 19. -

Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: a Case Study of Hyderabad Police

Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION By A. KUMARA SWAMY (Research Scholar) Under the Supervision of Dr. P. MOHAN RAO Associate Professor Railway Degree College Department of Public Administration Osmania University DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION University College of Arts and Social Sciences Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana-INDIA JANUARY – 2018 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION University College of Arts and Social Sciences Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana-INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police”submitted by Mr. A.Kumara Swamy in fulfillment for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration is an original work caused out by him under my supervision and guidance. The thesis or a part there of has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. (Signature of the Guide) Dr. P. Mohan Rao Associate Professor Railway Degree College Department of Public Administration Osmania University, Hyderabad. 2 DECLARATION This thesis entitled “Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police” submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration is entity original and has not been submitted before, either or parts or in full to any University for any research Degree. A. KUMARA SWAMY Research Scholar 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am thankful to a number of individuals and institution without whose help and cooperation, this doctoral study would not have been possible. -

Designation & Name of Officer (North Goa)

Sr. Designation & Name of Officer (North Goa) Office Fax Mobile No. Phone 1. Control Room Officer (CRO) 2428400 2428489 7875756000 2428967 2. Women Helpline SPCR Panaji 1091 -- 3. Women Whats app Messenger -- -- 7875756177 4. Senior Citizen Helpline SPCR Panaji 1090 -- 5. Anti-Terror & Coastal Helpline SPCR Panaji 1093 -- 6. Vigilance Helpline at SPCR Panaji -- 7030100000 7. District Police Control Room Porvorim 2416251 2416251 8. Control Room / DCC Margao 2700142 7875756110 (Exchange) 9. Director General of Police Shri Mukesh Kumar Meena, IPS 2428360 2428073 10. Inspector General of Police (Costal Security), (HQ) Shri Rajesh Kumar, IPS 2428738 2428738 Supervise functioning of:- SP(HQ), SP(L&V), PTS, Training, IRBn, Election Cell, Motor Transport, SP(Home Guard & Civil Defence), SP(EOC) 11. Dy. Inspector General of Police (Range) Shri Parmaditya, IPS 2420883 2421025 Supervise function of:- SP(N), SP(S), SP(Trf.). SP(Crime), wireless & Communication, SPCR, ANC, SB, Head of SIT to investigation mining related cases. (Nodal Officer for Public Health Response to COVID-19) Email:[email protected] 12. Superintendent of Police, Head Quarter Shri Abhishek Dhania, IPS 2428124 2422672 7875756008 13. Superintendent of Police, North-Goa Shri Utkrisht Prasoon, IPS 2416100 2416243 7875756013 14. Superintendent of Police, South-Goa Shri Pankaj Kumar Singh, IPS 2732218 2733864 7875756016 (Additional Charge Supervise PCR South) 15. Superintendent of Police –Crime , SIT (Mining Land Grap), Shri Shobit D. Saksena, IPS 2443082 7875756020 Additional Charge of SP, ATS, (Supervise SIT Mining), SP Cyber, SCRB 16. Superintendent of Police Traffic Shri. Arvind Gawas, IPS 2422112 2422112 7875756005 17. Superintendent of Police / SDPO MARGAO Shri Harish Madkaikar 2714449 2714449 7875756043 (2017 Batch of Joint AGMUT Cadre) 7875756108 18. -

Laws Protecting Sex Worker & Condition of Sex Worker

© 2021 JETIR June 2021, Volume 8, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) LAWS PROTECTING SEX WORKER & CONDITION OF SEX WORKER DURING LOCKDOWN RISHAB KUMAR, 4th year student at UPES, Dheradun. Contact no.- 9719942006, Dheradun, Uttrakhand, INDIA ABSTRACT Sex work many times considered by images of compulsion, poverty, insolvency and lack of agency and sex worker as merely being oppressed victims of society and they were treat bias as compare to other group of society and during lockdown in the country sex worker face this type of biasness in this paper I will discuss about this biasness and problems faced by the sex worker during lockdown and then how supreme court take steps to protect the sex worker during pandemic. My research highlights the history of the prostitution in India that how the prostitution is evolved and how this sector is prominent in history of India. This research also highlight what legislation make by the government to protect the sex worker and the some laws to prohibit the trafficking of women and girl child in the prostitution and the problems faces by the sex worker and the possible solution to the problems. And the most important question will discuss in that research paper shall India legalize prostitution? Key words – Sex worker, legislation, Covid-19, Pandemic. TABLE OF CONTENT Page no. 1. INTRODUCTION 2. History of prostitution 3. Legislation on the sex worker 4. Shall India legalize prostitution 5. Condition of sex worker during lockdown 6. Conclusion 7. References JETIR2106255 Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR) www.jetir.org b800 © 2021 JETIR June 2021, Volume 8, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) INTRODUCTION Prostitution is deemed to be the oldest profession and trases of this profession was found in ancient Babylons1. -

Functions, Roles and Duties of Police in General

Chapter 1 Functions, Roles and Duties of Police in General Introduction 1. Police are one of the most ubiquitous organisations of the society. The policemen, therefore, happen to be the most visible representatives of the government. In an hour of need, danger, crisis and difficulty, when a citizen does not know, what to do and whom to approach, the police station and a policeman happen to be the most appropriate and approachable unit and person for him. The police are expected to be the most accessible, interactive and dynamic organisation of any society. Their roles, functions and duties in the society are natural to be varied, and multifarious on the one hand; and complicated, knotty and complex on the other. Broadly speaking the twin roles, which the police are expected to play in a society are maintenance of law and maintenance of order. However, the ramifications of these two duties are numerous, which result in making a large inventory of duties, functions, powers, roles and responsibilities of the police organisation. Role, Functions and Duties of the Police in General 2. The role and functions of the police in general are: (a) to uphold and enforce the law impartially, and to protect life, liberty, property, human rights, and dignity of the members of the public; (b) to promote and preserve public order; (c) to protect internal security, to prevent and control terrorist activities, breaches of communal harmony, militant activities and other situations affecting Internal Security; (d) to protect public properties including roads, -

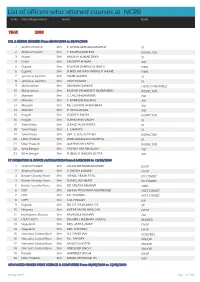

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT.