Anglo-Scottish Relations from Gentle to Rough Wooing, 1543-1547

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tartan As a Popular Commodity, C.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), Pp

Tuckett, S. (2016) Reassessing the romance: tartan as a popular commodity, c.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), pp. 182-202. (doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0295) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/112412/ Deposited on: 22 September 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk SALLY TUCKETT Reassessing the Romance: Tartan as a Popular Commodity, c.1770-1830 ABSTRACT Through examining the surviving records of tartan manufacturers, William Wilson & Son of Bannockburn, this article looks at the production and use of tartan in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While it does not deny the importance of the various meanings and interpretations attached to tartan since the mid-eighteenth century, this article contends that more practical reasons for tartan’s popularity—primarily its functional and aesthetic qualities—merit greater attention. Along with evidence from contemporary newspapers and fashion manuals, this article focuses on evidence from the production and popular consumption of tartan at the turn of the nineteenth century, including its incorporation into fashionable dress and its use beyond the social elite. This article seeks to demonstrate the contemporary understanding of tartan as an attractive and useful commodity. Since the mid-eighteenth century tartan has been subjected to many varied and often confusing interpretations: it has been used as a symbol of loyalty and rebellion, as representing a fading Highland culture and heritage, as a visual reminder of the might of the British Empire, as a marker of social status, and even as a means of highlighting racial difference. -

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

Mary Stuart and Elizabeth 1 Notes for a CE Source Question Introduction

Mary Stuart and Elizabeth 1 Notes for a CE Source Question Introduction Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587) Mary was the daughter of James V of Scotland and Mary of Guise. She became Queen of Scotland when she was six days old after her father died at the Battle of Solway Moss. A marriage was arranged between Mary and Edward, only son of Henry VIII but was broken when the Scots decided they preferred an alliance with France. Mary spent a happy childhood in France and in 1558 married Francis, heir to the French throne. They became king and queen of France in 1559. Francis died in 1560 of an ear infection and Mary returned to Scotland a widow in 1561. During Mary's absence, Scotland had become a Protestant country. The Protestants did not want Mary, a Catholic and their official queen, to have any influence. In 1565 Mary married her cousin and heir to the English throne, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. The marriage was not a happy one. Darnley was jealous of Mary's close friendship with her secretary, David Rizzio and in March 1566 had him murdered in front of Mary who was six months pregnant with the future James VI and I. Darnley made many enemies among the Scottish nobles and in 1567 his house was blown up. Darnley's body was found outside in the garden, he had been strangled. Three months later Mary married the chief suspect in Darnley’s murder, the Earl of Bothwell. The people of Scotland were outraged and turned against her. -

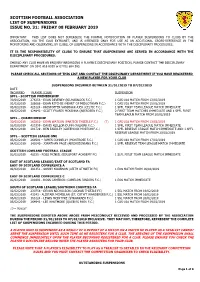

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

Form Foreign Policy Took- Somerset and His Aims: Powers Change? Sought to Continue War with Scotland, in Hope of a Marriage Between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots

Themes: How did relations with foreign Form foreign policy took- Somerset and his aims: powers change? Sought to continue war with Scotland, in hope of a marriage between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots. Charles V up to 1551: The campaign against the Scots had been conducted by Somerset from 1544. Charles V unchallenged position in The ‘auld alliance’ between Franc and Scotland remained, and English fears would continue to be west since death of Francis I in dominated by the prospect of facing war on two fronts. 1547. Somerset defeated Scots at Battle of Pinkie in September 1547. Too expensive to garrison 25 border Charles won victory against forts (£200,000 a year) and failed to prevent French from relieving Edinburgh with 10,000 troops. Protestant princes of Germany at In July 1548, the French took Mary to France and married her to French heir. Battle of Muhlberg, 1547. 1549- England threatened with a French invasion. France declares war on England. August- French Ottomans turned attention to attacked Boulogne. attacking Persia. 1549- ratified the Anglo-Imperial alliance with Charles V, which was a show of friendship. Charles V from 1551-1555: October 1549- Somerset fell from power. In the west, Henry II captured Imperial towns of Metz, Toul and Verdun and attacked Charles in the Form foreign policy-Northumberland and his aims: Netherlands. 1550- negotiated a settlement with French. Treaty of In Central Europe, German princes Somerset and Boulogne. Ended war, Boulogne returned in exchange for had allied with Henry II and drove Northumberland 400,000 crowns. England pulled troops out of Scotland. -

Bygone Church Life in Scotland

*«/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF Old Authors Farm Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bygonechurchlifeOOandrrich law*""^""*"'" '* BYGONE CHURCH LIFE IN SCOTLAND. 1 f : SS^gone Cburcb Xife in Scotland) Milltam Hnbrewa . LONDON WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO., 5. FARRINGDON AVENUE, E.G. 1899. GIFT Gl f\S2S' IPreface. T HOPE the present collection of new studies -*- on old themes will win a welcome from Scotsmen at home and abroad. My contributors, who have kindly furnished me with articles, are recognized authorities on the subjects they have written about, and I think their efforts cannot fail to find favour with the reader. V William Andrews. The HuLl Press, Christmas Eve^ i8g8. 595 Contents. PAGE The Cross in Scotland. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. i Bell Lore. By England Hewlett 34 Saints and Holy Wells. By Thomas Frost ... 46 Life in the Pre-Reformation Cathedrals. By A. H. Millar, F.S.A., Scot 64 Public Worship in Olden Times. By the Rev. Alexander Waters, m.a,, b.d 86 Church Music. By Thomas Frost 98 Discipline in the Kirk. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. 108 Curiosities of Church Finance. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 130 Witchcraft and the Kirk. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 162 Birth and Baptisms, Customs and Superstitions . 194 Marriage Laws and Customs 210 Gretna Green Gossip 227 Death and Burial Customs and Superstitions . 237 The Story of a Stool 255 The Martyrs' Monument, Edinburgh .... 260 2 BYGONE CHURCH LIFE. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Palaces & Castles

PALACESPALACES, & Castles were built for wealthy people to live in. As so many wealthy people lived in castles, there were usually lots of lovely things that CASTLESCASTLES people wanted to steal. Sometimes enemies wanted the whole castle! Because of this, it was very important that castles were protected against enemies. Let’s find out more about parts of the castles that we would be able to see in Scotland! Then try the quiz on page 8! LINLITHGOW PALACE Can you spot ? The bailey It was a courtyard in the middle of the castle. It was a large piece of open ground. Arrow loops, or slits, They were used to defend the castle from invaders. These narrow slits were cut into the stone walls and used to shoot arrows through. The flying arrows would come as a big surprise to the invaders down below! Linlithgow Palace STIRLING CASTLE Can you spot ? The gatehouse The gatehouse was a strong building built over the gateway. The barbican The barbican was a wall which jutted out around the gateway or might be like a tower. Its main job was to add strength to the gatehouse. The battlement Battlements were basically small defensive walls at the top of a castles main walls with gaps to fire arrows through. EDINBURGH CASTLE The portcullis A portcullis is a heavy gate that was lowered down by chains from above the gateway. It comes from a French words ‘porte coulissante,’ which means sliding door. DIRLETON CASLTLE Murder Holes They are holes or gaps above a castle’s doorway to drop things on anyone trying to come in uninvited. -

Catalogue of Books and Monographs

Catalogue of Books and Monographs (last updated Nov 2006) The Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Scotland. Edinburgh, RCAHMS. Doon Hill: 3 diagrams of structures: 1) two structures, 2) area (with pencil marks) 3) halls A and B. Dumbarton Publication Drawings: 1) Description of illustrations 2) 16 diagrams and maps (4 maps of Scotland, rest diagrams (some cross-section). Kinnelhead and Drannandow: Maps of Kinnelhead sites (1-4, 6) and Drannandow (5, 7), with natural features, structures. Paper, some sellotaped together and fragile. North of Scotland Archaeological Services. Round House & Compass Circles: 2 diagrams 1) on left has concentric circles, probably done with compass, with numbers 2) on right plan of Round house (?) P2 with numbers and word 'Deu . ' (1923). A guide to the Anglo-Saxon and foreign teutonic antiquities in the Department of British and Mediaeval Antiquities. London, British Museum. (1925). A guide to antiquities of the early Iron Age in the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities. Oxford, Oxford University Press for the British Museum. (1926). A guide to antiquities of the Stone Age in the Department of British and Mediaeval Antiquities. Oxford, Oxford University Press for the British Museum. (1927). London and the Vikings. London. (1936). Proceedings of the Warrington Literary and Philosophical Society 1933-1936. Warrington, John Walker & Co. Ltd. (1937). The Archeological Journal. London, Royal Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 94 (XCIV). (1940). Medieval catalogue. London, The London Museum. (1947). Field Archaeology. Some Notes for Beginners issued by the Ordnance Survey. London, HMSO. (1947). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial. A Provisional Guide. London, Trustees of the British Museum. -

4, Excavations at Alt Gl

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, (1990)0 12 , 95-149, fiche 2:A1-G14 Reconnaissance excavations on Early Historic fortification othed an s r royal site Scotlandn si , 1974-84 , Excavation:4 t GlutAl t ,sa Clyde Rock, Strathclyde, 1974-75 Leslie Alcock Elizabetd *an AlcockhA * SUMMARY As part of a long-term programme of research historically-documentedon fortifications, excava- tions were carried 1974-75in out Dumbartonat Castle, anciently knownClut Alt Clydeor as Rock. These disproved hypothesisthe that nucleara fort, afterpatternthe of Dunadd Dundurn,or couldbe identified on the Rock, but revealed a timber-and-rubble defence of Early Historic date overlooking the isthmus which links the Rock to the mainland. Finds of especial interest include the northernmost examples of imported Mediterranean amphorae of the sixth century AD, and fragments from at least six glass vessels ofgermanic manufacture. Discussion centres on early medieval harbour sites and trade in northern and western Britain. A detailed excavation record and finds catalogue will be found in the microfiche. CONTENTS EXCAVATION SYNTHESIS & DISCUSSION (illuS 1-19) Introduction: character of the excavation and report..................................... 96 Early history.......................................................................8 9 . Clyd setting...........................................................es it Roc d kan 9 9 . The excavation: structures and finds ................................................... 104 Synthesis: history, artefact structures& s ..............................................3 -

Outlander-Itinerary-Trade.Pdf

Outlander Based on the novels by Diana Gabaldon, this historical romantic drama has been brought to life on-screen with passion and verve and has taken the TV Doune Castle world by storm. The story begins in 1945 when WWII nurse Claire Randall, on a second honeymoon in the Scottish Highlands with her husband Frank, is transported back to 1743 where she encounters civil war and dashing Scottish warrior Jamie Fraser. Follow in the footsteps of Claire and Jamie and visit some of Scotland’s most iconic heritage attractions. Linlithgow Palace Aberdour Castle Blackness Castle www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/outlander Ideal for groups or individuals visiting a number of properties, holders can access as many Historic Scotland sites as they wish which includes a further 70 sites in addition to those in our itineraries. Passes Outlander is a fascinating story that combines fantasy, can be used as part of a package or offered as an romance and adventure showcasing Scotland’s rich N optional add-on. landscape and dramatic history in the process.Shetland 150 miles Our Explorer Pass makes it simple to travel around the sites – Includes access to all 78 Historic Scotland attractions that feature both in the novels and television series and – 20% commission on all sales offers excellent value for money. Below we have suggested – Flexible Entry Times itineraries suitable for use with our 3 or 7 day pass. 7 Seven day itinerary 6 1 5 Day 1 Doune Castle (see 3 day itinerary) 2 Day 2 Blackness Castle (see 3 day itinerary) 3 Day 3 Linlithgow Palace (see 3 day itinerary) 4 Aberdour Castle and Gardens 1 4 Day 4 3 2 This splendid ruin on the Fife Coast was the luxurious Renaissance home of Regent Morton, once Scotland’s most powerful man.