Nationalism and Welsh Writing in Comparative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

Emyr Humphreys Catalogue

EMYR HUMPHREYS 100 @WelshBooks / @LlyfrauCymru CYNGOR LLYFRAU CYMRU gwales.com WELSH BOOKS COUNCIL CYNGOR LLYFRAU CYMRU WELSH BOOKS COUNCIL Emyr Humphreys Emyr Humphreys, born in 1919 in Ganed Emyr Humphreys ym Mhrestatyn Prestatyn, north Wales, is one of the yng ngogledd Cymru ym 1919. Mae’n un foremost Welsh novelists writing in o nofelwyr mwyaf blaengar Cymru. Yn English. He has published over twenty ystod ei yrfa lenyddol, cyhoeddodd dros novels, which include such classics as ugain o nofelau, gan gynnwys clasuron A Toy Epic (1958), Outside the House of megis A Toy Epic (1958), Outside the Baal (1965) and The Land of the Living, House of Baal (1965) a The Land of an epic sequence of seven novels the Living – cyfres epig o saith nofel yn charting the political and cultural history adrodd hanes gwleidyddol a diwylliannol of twentieth-century Wales. He has also Cymru yn yr ugeinfed ganrif. Mae hefyd written plays for stage and television, wedi ysgrifennu dramâu ar gyfer y llwyfan short stories and poems. He was a theledu, straeon byrion a chasgliadau o described by the poet R. S. Thomas as gerddi. Disgrifiwyd ef gan R. S. Thomas fel ‘the supreme interpreter of Welsh life’. ‘the supreme interpreter of Welsh life’. In the early 40s, as a conscientious Yn ystod ei gyfnod yn astudio hanes objector and whilst studying history at ym Mhrifysgol Cymru, Aberystwyth, the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, ymrestrodd yn wrthwynebwr cydwybodol he was sent to work on the land during pan ddechreuodd yr Ail Ryfel Byd. Wedi the Second World War. He subsequently iddo fwrw sawl cyfnod yn y Dwyrain went as a war relief worker to the Middle Canol ac yn yr Eidal yn gweithio ym maes East and then to Italy. -

The Role and Importance of the Welsh Language in Wales's Cultural Independence Within the United Kingdom

The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain Scaglia To cite this version: Sylvain Scaglia. The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom. Linguistics. 2012. dumas-00719099 HAL Id: dumas-00719099 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00719099 Submitted on 19 Jul 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DU SUD TOULON-VAR FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MASTER RECHERCHE : CIVILISATIONS CONTEMPORAINES ET COMPAREES ANNÉE 2011-2012, 1ère SESSION The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain SCAGLIA Under the direction of Professor Gilles Leydier Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 WALES: NOT AN INDEPENDENT STATE, BUT AN INDEPENDENT NATION ........................................................ -

Wales Sees Too Much Through Scottish Eyes

the welsh + Peter Stead Dylan at 100 Richard Wyn Jones and Roger Scully Do we need another referendum? John Osmond Learning from Mondragon Stuart Cole A railway co-op for Wales David Williams Sliding into poverty James Stewart A lost broadcasting service Peter Finch Wales sees too Talking to India Trevor Fishlock The virtues of left handednesss much through Osi Rhys Osmond Two lives in art Ned Thomas Scottish eyes Interconnected European stories M. Wynne Thomas The best sort of crank www.iwa.org.uk | Summer 2012 | No. 47 | £8.99 The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Public Sector Private Sector Voluntary Sector • Aberystwyth University • ABACA Limited • Aberdare & District Chamber • ACAS Wales • ACCA Cymru Wales of Trade & Commerce • Bangor University • Beaufort Research Ltd • Cardiff & Co • BBC Cymru Wales • BT • Cartrefi Cymru • British Waterways • Call of the Wild • Cartrefi Cymunedol Community • Cardiff & Vale College / Coleg • Castell Howell Foods Housing Cymru Caerdydd a’r Fro • CBI Wales • Community – the Union for Life • Cardiff Council • Core • Cynon Taf Community Housing Group • Cardiff School of Management • Darwin Gray • Disability Wales • Cardiff University • D S Smith Recycling • EVAD Trust • Cardiff University Library • Devine Personalised Gifts • Federation of Small Businesses Wales • Centre for Regeneration Excellence • Elan Valley Trust -

Welsh-Medium and Bilingual Education

WELSH-MEDIUM AND BILINGUAL EDUCATION CATRIN REDKNAP W. GWYN LEWIS SIAN RHIANNON WILLIAMS JANET LAUGHARNE Catrin Redknap leads the Welsh Language Board pre-16 Education Unit. The Unit maintains a strategic overview of Welsh-medium and bilingual education and training. Before joining the Board she lectured on Spanish and Sociolinguistics at the University of Cardiff. Gwyn Lewis lectures in the College of Education and Lifelong Learning at the University of Wales, Bangor, with specific responsibility for Welsh language education within the primary and secondary teacher training courses. A joint General Editor of Education Transactions, his main research interests include Welsh-medium and bilingual education, bilingualism and child language development. Sian Rhiannon Williams lectures on History at the University of Wales Institute Cardiff. Her research interests include the history of women in the teaching profession and other aspects of the history of education in Wales. Based on her doctoral thesis, her first book was a study of the social history of the Welsh language in industrial Monmouthshire. She has published widely on the history of Gwent and on women’s history in Wales, and has co- edited a volume on the history of women in the south Wales valleys during the interwar period. She is reviews editor of the Welsh Journal of Education. Janet Laugharne lectures in the Cardiff School of Education, University of Wales Institute Cardiff, and is the School’s Director of Research. She is interested in bilingualism and bilingual education and has written on this area in relation to Welsh, English and other community languages in Britain. She is one of the principal investigators for a project, commissioned by the Welsh Assembly Government, to evaluate the implementation of the new Foundation Stage curriculum for 3-7 year-olds in Wales. -

New Perspectives on Modern Wales

New Perspectives on Modern Wales New Perspectives on Modern Wales: Studies in Welsh Language, Literature and Social Politics Edited by Sabine Asmus and Katarzyna Jaworska-Biskup New Perspectives on Modern Wales: Studies in Welsh Language, Literature and Social Politics Edited by Sabine Asmus and Katarzyna Jaworska-Biskup Reviewer: Prof. dr. Eduard Werner This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Sabine Asmus, Katarzyna Jaworska-Biskup and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2191-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2191-9 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................. 3 Welsh or British in Times of Trouble? Shaping Welsh Culture and Identity during the Second World War Martin Andrew Hanks CHAPTER TWO .......................................................................................... 31 Local or National? Gender, Place and Identity in Post-Devolution Wales’ Literature Rhiannon Heledd Williams CHAPTER THREE -

O Dinopolis I Fetropolis

O DINOPOLIS I FETROPOLIS Arolwg o lanw a thrai achosion Ymneilltuol Cymraeg yn Llanelli a Llundain 1714-2014 Traethawd a gyflwynir i Brifysgol Cymru Y Drindod Dewi Sant yn unol â chanllawiau ar gyfer y radd PhD (Gweithiau Cyhoeddedig) 2018 HUW EDWARDS Llundain DIOLCHIADAU Dymunaf ddiolch i’m gwraig a’m plant am eu hamynedd a’u cefnogaeth gyson gydol cyfnod hir o ymchwilio ac ysgrifennu. Carwn ddiolch yn ogystal i’m tiwtoriaid – y Dr Robert Pope a’r Dr Catrin Williams yn bennaf yn eu plith – a holl staff y Brifysgol am eu caredigrwydd a’u parodrwydd i gynnig cymorth a chyngor. Yr wyf yn hynod ddyledus i’r Is-Ganghellor, yr Athro Medwin Hughes, am ei anogaeth a’i ofal. O DINOPOLIS I FETROPOLIS Arolwg o lanw a thrai achosion Ymneilltuol Cymraeg yn Llanelli a Llundain 1714-2014 CYNNWYS 1. Cyflwyniad 2. Capeli Llanelli – hanesyddiaeth 3. Capeli Llanelli – braslun a ffynonellau 4. Capeli Llanelli – cyfraniad 5. City Mission a’r erthyglau – hanesyddiaeth 6. City Mission a’r erthyglau – braslun a ffynonellau 7. City Mission a’r erthyglau – cyfraniad 8. Casgliadau 9. Llyfryddiaeth gyflawn Rhif geiriau’r traethawd: 27,450. PRIF GYFEIRIADAU (CL) Edwards, H. (2009) Capeli Llanelli: Our Rich Heritage. Caerfyrddin: Cyngor Sir Gaerfyrddin, tt. 550. (CM) Edwards, H. (2014) City Mission: The Story of London’s Welsh Chapels. Talybont: Y Lolfa, pp. 368. (CT) Edwards, H. (2016) ‘Codi trywydd: y bregeth Gymraeg yn Llundain cyn cyfnod Howel Harris’, yn Cylchgrawn Cymdeithas Hanes y Methodistiaid Calfinaidd, 40 (2016), 27-46. (OT) Edwards, H. (2017) ‘On the trail of Ginshop Jones: Welsh Nonconformists in Eighteenth-Century London’, in Welsh History Review, 28/3 (2017), 470-86. -

The Height of Its Womanhood': Women and Genderin Welsh Nationalism, 1847-1945

'The height of its womanhood': Women and genderin Welsh nationalism, 1847-1945 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kreider, Jodie Alysa Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 04:59:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280621 'THE HEIGHT OF ITS WOMANHOOD': WOMEN AND GENDER IN WELSH NATIONALISM, 1847-1945 by Jodie Alysa Kreider Copyright © Jodie Alysa Kreider 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partia' Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3145085 Copyright 2004 by Kreider, Jodie Alysa All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3145085 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

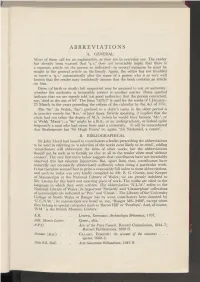

ABBREVIATIONS Use. the Reader That

ABBREVIATIONS A. GENERAL Most of these call for no explanation, as they are in everyday use. The reader has already been warned that 'q.v.' does not invariably imply that there is a separate article on the person so indicated—in several instances he must be sought in the general article on his family. Again, the editor has not troubled to insert a 'q.v.' automatically after the name of a person who is so very well known that the reader may confidently assume that the book contains an article on him. Dates (of birth or death) left unqueried may be assumed to rest on authority: whether the authority is invariably correct is another matter. Dates queried indicate that we are merely told (on good authority) that the person concerned, say, 'died at the age of 64'. The form '1676/7' is used for the weeks of 1 January- 25 March in the years preceding the reform of the calendar by the Act of 1751. The 'Sir' (in Welsh, 'Syr') prefixed to a cleric's name in the older period is in practice merely the 'Rev.' of later times. Strictly speaking, it implied that the cleric had not taken the degree of M.A. (when he would have become 'Mr.', or in Welsh 'Mastr'); a 'Sir' might be a B.A., or an undergraduate, or indeed quite frequently a man who had never been near a university. It will be remembered that Shakespeare has 'Sir Hugh Evans' or, again, 'Sir Nathaniel, a curate'. B. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL Sir John Lloyd had issued to contributors a leaflet prescribing the abbreviations to be used in referring to 'a selection of the works most likely to be cited', adding 'contributors will abbreviate the titles of other works, but the abbreviations should not be such as to furnish no clue at all to the reader when read without context'. -

Let's Electrify Scranton with Welsh Pride Festival Registrations

Periodicals Postage PAID at Basking Ridge, NJ The North American Welsh Newspaper® Papur Bro Cymry Gogledd America™ Incorporating Y DRYCH™ © 2011 NINNAU Publications, 11 Post Terrace, Basking Ridge, NJ 07920-2498 Vol. 37, No. 4 July-August 2012 NAFOW Mildred Bangert is Honored Festival Registrations Demand by NINNAU & Y DRYCH Mildred Bangert has dedicated a lifetime to promote Calls for Additional Facilities Welsh culture and to serve her local community. Now that she is retiring from her long held position as Curator of the By Will Fanning Welsh-American Heritage Museum she was instrumental SpringHill Suites by Marriott has been selected as in creating, this newspaper recognizes her public service additional Overflow Hotel for the 2012 North by designating her Recipient of the 2012 NINNAU American Festival of Wales (NAFOW) in Scranton, CITATION. Read below about her accomplishments. Pennsylvania. (Picture on page 3.) This brand new Marriott property, opening mid-June, is located in the nearby Montage Mountain area and just Welsh-American Heritage 10 minutes by car or shuttle bus (5 miles via Interstate 81) from the Hilton Scranton and Conference Center, the Museum Curator Retires Festival Headquarters Hotel. By Jeanne Jones Jindra Modern, comfortable guest suites, with sleeping, work- ing and sitting areas, offer a seamless blend of style and After serving as curator of the function along with luxurious bedding, a microwave, Welsh-American Heritage for mini-fridge, large work desk, free high-speed Internet nearly forty years, Mildred access and spa-like bathroom. Jenkins Bangert has announced Guest suites are $129 per night (plus tax) and are avail- her retirement. -

Adroddiad Blynyddol 1979

ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL / ANNUAL REPORT 1978-79 J D K LLOYD 1979001 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mr J D K Lloyd, O.B.E., D.L., M.A., LL.D., F.S.A., Garthmyl, Powys. Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1978-79 Disgrifiad / Description Two deed boxes containing papers of the late Dr. J. D. K. Lloyd (1900-78), antiquary, author of A Guide to Montgomery and of various articles on local history, formerly mayor of Montgomery and high sheriff of Montgomeryshire, and holder of several public and academic offices [see Who's Who 1978 for details]. The one box, labelled `Materials for a History of Montgomery', contains manuscript volumes comprising a copy of the glossary of the obsolete words and difficult passages contained in the charters and laws of Montgomery Borough by William Illingworth, n.d. [watermark 1820), a volume of oaths of office required to be taken by officials of Montgomery Borough, n.d., [watermark 1823], an account book of the trustees of the poor of Montgomery in respect of land called the Poors Land, 1873-96 (with map), and two volumes of notes, one containing notes on the bailiffs of Montgomery for Dr. Lloyd's article in The Montgomeryshire Collections, Vol. 44, 1936, and the other containing items of Montgomery interest extracted from Archaeologia Cambrensis and The Montgomeryshire Collections; printed material including An Authentic Statement of a Transaction alluded to by James Bland Burgess, Esq., in his late Address to the Country Gentlemen of England and Wales, 1791, relating to the regulation of the practice of county courts, Letters to John Probert, Esq., one of the devisees of the late Earl of Powis upon the Advantages and Defects of the Montgomery and Pool House of Industry, 1801, A State of Facts as pledged by Mr. -

Pages Ffuglen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page I

Y Meddwl a’r Dychymyg Cymreig FfugLen Y Ddelwedd o Gymru yn y Nofel Gymraeg o Ddechrau’r Chwedegau hyd at 1990 Enid Jones Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page i FfugLen Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page ii Y MEDDWL A’R DYCHYMYG CYMREIG Golygydd Cyffredinol John Rowlands Cyfrolau a ymddangosodd yn y gyfres hyd yn hyn: 1. M. Wynn Thomas (gol.), DiFfinio Dwy Lenyddiaeth Cymru (1995) 2. Gerwyn Wiliams, Tir Neb (1996) (Llyfr y Flwyddyn 1997; Enillydd Gwobr Goffa Ellis Griffith) 3. Paul Birt, Cerddi Alltudiaeth (1997) 4. E. G. Millward, Yr Arwrgerdd Gymraeg (1998) 5. Jane Aaron, Pur fel y Dur (1998) (Enillydd Gwobr Goffa Ellis Griffith) 6. Grahame Davies, Sefyll yn y Bwlch (1999) 7. John Rowlands (gol.), Y Sêr yn eu Graddau (2000) 8. Jerry Hunter, Soffestri’r Saeson (2000) (Rhestr Fer Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2001) 9. M. Wynn Thomas (gol.), Gweld Sêr (2001) 10. Angharad Price, Rhwng Gwyn a Du (2002) 11. Jason Walford Davies, Gororau’r Iaith (2003) (Rhestr Fer Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2004) 12. Roger Owen, Ar Wasgar (2003) 13. T. Robin Chapman, Meibion Afradlon a Chymeriadau Eraill (2004) 14. Simon Brooks, O Dan Lygaid y Gestapo (2004) (Rhestr Hir Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2005) 15. Gerwyn Wiliams, Tir Newydd (2005) 16. Ioan Williams, Y Mudiad Drama yng Nghymru 1880–1940 (2006) 17. Owen Thomas (gol.), Llenyddiaeth mewn Theori (2006) 18. Sioned Puw Rowlands, Hwyaid, Cwningod a Sgwarnogod (2006) 19. Tudur Hallam, Canon Ein Llên (2007) Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page iii Y MEDDWL A’R DYCHYMYG CYMREIG FfugLen Y Ddelwedd o Gymru yn y Nofel Gymraeg o Ddechrau’r Chwedegau hyd at 1990 Enid Jones GWASG PRIFYSGOL CYMRU CAERDYDD 2008 Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page iv h Enid Jones, 2008 Cedwir pob hawl.