Cultural Con Ict in Hong Kong Angles on a Coherent Imaginary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Twins Pte Ltd [email protected] 24 October

24 October 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Twelfth Scale Supreme Action Figure (Old Master Q) Announcing the pre-orders of "Old Master Q", in both "Colour" and "Black and White" versions! Officially licensed by OMQ ZMEDIA LTD, the classic "Old Master Q" character jumps from his illustrated digests to the toy-arena, with these 1/12th-scaled multi-articulated action figures scheduled for pre-orders, with a second quarter of 2019 release. "Old Master Q" also known as "老夫子" is a popular Hong Kong manhua created by Alfonso Wong, with over five decades of existence, from his first appearance in newspapers and magazines in Hong Kong in 1962, and later serialised in 1964, until its publication today! As well, the titular character and his friends has been made into many Cantonese and Mandarin cartoon animations, including feature films with live actors combined with advanced CGI graphics. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Master_Q) Great Twins is the Worldwide Licensee for "Old Master Q" 1/12 figure line, and here is your opportunity to collect and play with your distinctively Asian favourite character! Old Master Q features an (approx.) 16cm tall Action body with over 25 points of articulation, clothed by a set of fine cutting costume and a pair of shoes, and possesses a magnetic hat (that can attach stably on the head), the iconic head sculpture of "Old Master Q", and three pairs of interchangeable hands! Additional accessories include a Calligraphy Board and a Figure Stand. The "Exclusive" version will also include the Dog that appears in the -

Book of Abstract Cantonese Syntax

THE 1ST INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP ON CANTONESE SYNTAX BOOK OF ABSTRACTS OLOMOUC 2019 THE 1ST INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP ON CANTONESE SYNTAX BOOK OF ABSTRACTS June 27-28, 2019 Palacký University in Olomouc Sinophone Borderlands – Interaction at the Edges reg. no. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000791 Excellent research Website: http://sinofon.cz/ Contact: [email protected] The 1st International Workshop on Cantonese Syntax The 1st International Workshop on Cantonese Syntax will be held on 27–28 June, 2019, Palacký University in Olomouc, Czech Republic. It aims to provide a forum for researchers to meet and discuss current development in Cantonese Syntax and to promote the study of Cantonese syntax in Central Europe. 3 Program 14:30–15:00 Relative clauses in Cantonese June 28, 2019 Jiaying Huang (Paris Diderot University) Moderator: Lisa Cheng 09:00–10:00 Verb stranding ellipsis: evidence from Cantonese Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng (Leiden University) 15:00–15:15 COFFEE BREAK June 27, 2019 Moderator: Joanna Sio 15:15–16:15 A Cantonese perspective on the head and the tail of the 09:00–10:00 On the hierarchical structure of Cantonese structure of the verbal domain 10:00–10:15 COFFEE BREAK sentence-final particle Rint Sybesma (Leiden University) Sze-Wing Tang (Chinese University of Hong Kong) 10:15–10:45 Morpho-syntax of non-VO separable compound verbs in Moderator: Joanna Sio Cantonese Moderator: Joanna Sio Sheila S.L. Chan and Lawrence Cheung (both Chinese 16:15–18:00 Reception (Konvikt Garden) University of Hong Kong) 10:00–10:15 COFFEE BREAK Moderator: Rint -

Mainland Hong Kong

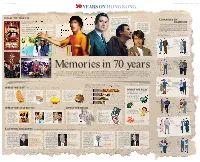

6 | Monday, October 21, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY 7 In 1980, the Hong Kong TV series Wong Kar-wai’s fi lm, Days of Being Wild, played by Chow in 1990, brought Leslie Cheung his first Yun-fat, The Bund, Best Actor trophy in the Hong Kong Film Popular mainland TV dramas in HK swept up both Hong Awards. Along with many other classical and TVB rating rankings Kong and Chinese diverse screen images In the 1990s, Hong Kong mainland television he created, Cheung actor and director Stephen Fashion changes over time. But closer interaction and mutual infl u- Ye a r Drama Ranking In the ’70s, Hong Kong audiences with its remains one Chow gained fame through ence can be seen through ever-changing fashion styles of Hong Kong 2000 Records of Kangxi’s Travel Incognito 10 kung fu star Bruce Lee checkered plots and of the most his unconventional “silly and the mainland over the past 70 years. The two parallel fashion took Chinese martial arts powerful theme song. iconic actors talk” humor, earning him styles began to overlap in the 1970s when Hong Kong movies and TV 2006 The Return of the Condor Heroes 3 to Hollywood for the fi rst in the city’s the nickname dramas dominated the Chinese-speaking world. The interaction of the time. His movies gained movie “the king of two places grew much more intense under the impact of globalization 2015 The Empress of China 2 enormous success around history. comedy”. in the 21st century. 2018 Story of Yanxi Palace 1 the world. -

Hong Kong Literature As Sinophone Literature = È'¯Èªžèªžç³

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 8 Issue 2 Vol. 8.2 & 9.1 八卷二期及九卷一期 Article 2 (2008) 1-1-2008 Hong Kong literature as Sinophone literature = 華語語系香港文學 初論 Shu Mei SHIH University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Shih, S.-m. (2008). Hong Kong literature as Sinophone literature = 華語語系香港文學初論. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 8.2&9.1, 12-18. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Hong Kong Literature as Sinophone Literature 華語語系香港文學初論 史書美 SHIH Shu-mei 加州大學洛杉磯分校亞洲語言文化系、 亞美研究系及比較文學系 Department of Comparative Literature, Asian Languages and Cultures, and Asian American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles A denotative meaning of the term “Sinophone,” as used by Sau-ling Wong in her work on Sinophone Chinese American literature to designate Chinese American literature written in Sinitic languages, is a productive way to start the investigation of the notion in terms of its connotative meanings.1 2 Connotation, by dictionary definition, is the practice that implies other characteristics and meanings beyond the term’s denotative meaning; ideas and feelings invoked in excess of the literal meaning; and, as a philosophical practice, the practice of identifying certain determining principles underlying the implied and invoked meanings, characteristics, ideas, and feelings. This short essay is a preliminary exploration of the connotative meanings of the category that I call Sinophone Hong Kong literature vis-a-vis the emergent field of Sinophone'studies as the study of Sinitic-language cultures, communities, and histories on the margins of China and Chineseness. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Shen, X.(2015). Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3190 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESTINATION HONG KONG: NEGOTIATING LOCALITY IN HONG KONG NOVELS 1945-1966 by Xianmin Shen Bachelor of Arts Tsinghua University, 2007 Master of Philosophy of Arts Hong Kong Baptist University, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Jie Guo, Major Professor Michael Gibbs Hill, Committee Member Krista Van Fleit Hang, Committee Member Katherine Adams, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Xianmin Shen, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several institutes and individuals have provided financial, physical, and academic supports that contributed to the completion of this dissertation. First the Department of Literatures, Languages, and Cultures at the University of South Carolina have supported this study by providing graduate assistantship. The Carroll T. and Edward B. Cantey, Jr. Bicentennial Fellowship in Liberal Arts and the Ceny Fellowship have also provided financial support for my research in Hong Kong in July 2013. -

Li Ling Ngan

Beyond Cantonese: Articulation, Narrative and Memory in Contemporary Sinophone Hong Kong, Singaporean and Malaysian Literature by Li Ling Ngan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Alberta © Li Ling Ngan, 2019 Abstract This thesis examines Cantonese in Sinophone literature, and the time- and place- specific memories of Cantonese speaking communities in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia after the year 2000. Focusing on the literary works by Wong Bik-wan (1961-), Yeng Pway Ngon (1947-) and Li Zishu (1971-), this research demonstrates how these three writers use Cantonese as a conduit to evoke specific memories in order to reflect their current identity. Cantonese narratives generate uniquely Sinophone critique in and of their respective places. This thesis begins by examining Cantonese literature through the methodological frameworks of Sinophone studies and memory studies. Chapter One focuses on Hong Kong writer Wong Bik-wan’s work Children of Darkness and analyzes how vulgar Cantonese connects with involuntary autobiographical memory and the relocation of the lost self. Chapter Two looks at Opera Costume by Singaporean writer Yeng Pway Ngon and how losing connection with one’s mother tongue can lose one’s connection with their familial memories. Chapter Three analyzes Malaysian writer Li Zishu’s short story Snapshots of Chow Fu and how quotidian Cantonese simultaneously engenders crisis of memory and the rejection of the duty to remember. These works demonstrate how Cantonese, memory, and identity, are transnationally linked in space and time. This thesis concludes with thinking about the future direction of Cantonese cultural production. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Hong Kong Cinema Since 1997: The Response of Filmmakers Following the Political Handover from Britain to the People’s Republic of China by Sherry Xiaorui Xu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Doctor of Philosophy HONG KONG CINEMA SINCE 1997: THE RESPONSE OF FILMMAKERS FOLLOWING THE POLITICAL HANDOVER FROM BRITAIN TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA by Sherry Xiaorui Xu This thesis was instigated through a consideration of the views held by many film scholars who predicted that the political handover that took place on the July 1 1997, whereby Hong Kong was returned to the sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from British colonial rule, would result in the “end” of Hong Kong cinema. -

Research Assessment Exercise 2020 Impact Case Study University: The

Research Assessment Exercise 2020 Impact Case Study University: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Unit of Assessment (UoA): 30 Title of case study: Promoting Public Awareness and Respect in Hong Kong Literature through the Endowment of Prof Lo Wai Luen (Xiao Si) (1) Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words) Prof Lo Wai Luen’s research has been instrumental in establishing and re-evaluating the literary legacy of Hong Kong literature. Lo’s editorial scholarship and investigative research on early works and writers, including the breakthrough discovery of ‘literary landscapes’, has provided new perspectives on the cultural mobility of one of the most vibrant cosmopolitans in the world. Via Lo’s new, definitive editions, biographical and oral historical publications, online archives and public lectures, Hong Kong literature has reached new global audiences and through the reconfigured insights have enhanced public awareness and respect in one’s own culture. (2) Underpinning research (indicative maximum 500 words) Prof Lo’s research on Hong Kong literature spans her entire period of employment at CUHK (1979-2002; emeritus 2002-present) and covers two main areas: (i) the scholarly editing of early literary works and documents; (ii) investigations of the literary field of Hong Kong, including the restoration of previously unknown or missing texts. Lo was the first scholar to give Hong Kong’s often fragmented literary productions the level of attention they deserve and to consolidate its importance as one of the seminal intellectual forces of twentieth century culture. The significance of Hong Kong literature reaches well beyond the literary sphere into questions of political and social organisation, national identity and the role of the intellectual, and Lo’s work highlights the importance of Hong Kong literature in each of these spheres. -

The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature 1919-1949

Research Assessment Exercise 2020 Impact Case Study University: The Education University of Hong Kong Unit of Assessment (UoA): 30 Chinese language & literature Title of case study: The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature 1919-1949 (1) Summary of the impact This study describes the reception and impact of the project of The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature 1919-1949 (The Compendium), reviewing the major cultural contributions of The Compendium made to the general public significantly beyond academia, including the local and overseas non-academic institutional and governmental recognitions, media coverage of all kinds, educational influence, and the huge reach the project created in its wealth of post-publication events held in a variety of venues in Hong Kong and overseas. The far-reaching impacts of The Compendium feature prominently in their contribution to cultural preservation, education, public memorialisation, regional cultural exchange, and tourism. (2) Underpinning research The idea of compiling a compendium of Hong Kong literature dates back to as early as the 1980s but was not materialised due to the lack of manpower and resource. In 2009, Prof Leonard Chan Kwok- kou and Dr Chan Chi-tak brought up the idea again, officially and systematically embarking on its realisation. Taking the Compendia of Chinese New Literature (Shanghai, 1935) as the prime predecessor, an editorial committee consisting of local literary specialists was subsequently formed and the project of “The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature” launched. In view of the daunting sea of literary works, the first series of the project as reported here focuses on the period of 1919- 1949. The twelve-volume Compendium is a landmark in Hong Kong literary studies and a much- awaited showcase of Hong Kong literature as a body of literary works that should be considered in its own right. -

Alternative Titles Index

VHD Index - 02 9/29/04 4:43 PM Page 715 Alternative Titles Index While it's true that we couldn't include every Asian cult flick in this slim little vol- ume—heck, there's dozens being dug out of vaults and slapped onto video as you read this—the one you're looking for just might be in here under a title you didn't know about. Most of these films have been released under more than one title, and while we've done our best to use the one that's most likely to be familiar, that doesn't guarantee you aren't trying to find Crippled Avengers and don't know we've got it as The Return of the 5 Deadly Venoms. And so, we've gathered as many alternative titles as we can find, including their original language title(s), and arranged them in alphabetical order in this index to help you out. Remember, English language articles ("a", "an", "the") are ignored in the sort, but foreign articles are NOT ignored. Hey, my Japanese is a little rusty, and some languages just don't have articles. A Fei Zheng Chuan Aau Chin Adventure of Gargan- Ai Shang Wo Ba An Zhan See Days of Being Wild See Running out of tuas See Gimme Gimme See Running out of (1990) Time (1999) See War of the Gargan- (2001) Time (1999) tuas (1966) A Foo Aau Chin 2 Ai Yu Cheng An Zhan 2 See A Fighter’s Blues See Running out of Adventure of Shaolin See A War Named See Running out of (2000) Time 2 (2001) See Five Elements of Desire (2000) Time 2 (2001) Kung Fu (1978) A Gai Waak Ang Kwong Ang Aau Dut Air Battle of the Big See Project A (1983) Kwong Ying Ji Dut See The Longest Nite The Adventures of Cha- Monsters: Gamera vs. -

Section 2: Measures

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Report on Measures to Protect and Promote the Diversity of Cultural Expressions Section 1: Summary The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (The Government) is committed to respecting the freedom of cultural and artistic creation and expression and providing an environment that supports the development of culture and the arts, both contemporary and traditional. On top of capital works expenditure, the Government spent over HK$2.8 billion in the arts and culture in 2010/11, which represents an increase of about 13% from HK$2.5 billion in 2007. Hong Kong has developed into a prominent arts and cultural hub in Asia with a very vibrant and diverse cultural scene. There are a large number of programmes and activities covering a wide range of arts disciplines, including music, opera, dance, drama, xiqu, film, visual arts as well as multimedia and multidisciplinary arts, comprising Chinese and Western cultures and encompassing traditional and contemporary arts going on throughout the year. There are over 1000 performing arts groups in Hong Kong. In 2008/09, there were 3,742 productions and 6,866 performances attracting a total attendance of 3.12 million. With regard to visual arts, apart from permanent exhibitions, there were 1, 439 other exhibitions, covering a wide range of art media. The attendance at public museums reached 5.44 million and library materials borrowed from the Hong Kong Public Libraries reached 60.06 million items in 2010. Looking forward, the West Kowloon Cultural District, comprising world-class arts and cultural facilities, will be developed to inject new momentum into Hong Kong’s arts and cultural landscape and provide enhanced cultural infrastructure to promote the diverse development of arts and culture in Hong Kong.