Interstellar Reddening Towards Six Small Areas in Puppis-Vela⋆⋆⋆

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

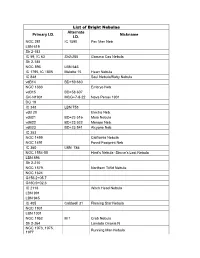

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Astronomy Quiz

Aryabhat Astronomy Quiz Study Material Part 2 Stars and Constellations The whole sky has been divided into star groups that move together. In the ancient astronomy, there were 48 constellations but in 1930, the astronomers of the whole world decided to reorganise the stellar objects, and modern astronomy goes with 88 constellations. A list of all constellations is given here : Names of 88 constellation in the whole sky Andromeda Circinus Lacerta Pisces Austrinus Antlia Columba Leo Puppis Apus Coma Berenices Leo Minor Pyxis Aquarius Corona Australis Lepus Reticulum Aquila Corona Borealis Libra Sagitta Ara Corvus Lupus Sagittarius Aries Crater Lynx Scorpius Auriga Crux Lyra Sculptor Bootes Cygnus Mensa Scutum Caelum Delphinus Microscopium Serpens Camelopardalis Dorado Monocerus Sextans Cancer Draco Musca Taurus Canes Venatici Equuleus Norma Telescopium Canis Major Eridanus Octans Triangulum Canis Minor Fornax Ophiuchus Triangulum Australe Capricornus Gemini Orion Tucana Carina Grus Pavo Ursa Major Cassiopeia Hercules Pegasus Ursa Minor Centaurus Horologium Perseus Vela Cepheus Hydra Phoenix Virgo Cetus Hydrus Pictor Volans Chamaeleon Indus Pisces Vulpecula Brightest Stars Each star is an individual with its own personality. Thousands are visible on any clear night far removed from city lights. Together, with the faint glow of myriad others, the tapestry of the celestial sphere is fashioned. Stars come in different colors, sizes, shapes and ages. One trait that makes a star unique is its brightness. Aryabhat Astronomy Quiz Study Material Volume 2 Page 1 Astronomers measure the brightness of a celestial object according to a system originally devised by Hipparchus in 120 B.C. Hipparchus ranked the brightness of stars in the sky on a scale of 1 to 6 as seen from the Earth. -

The Argo Navis Constellation

THE ARGO NAVIS CONSTELLATION At the last meeting we talked about the constellation around the South Pole, and how in the olden days there used to be a large ship there that has since been subdivided into the current constellations. I could not then recall the names of the constellations, but remembered that we talked about this subject at one of the early meetings, and now found it in September 2011. In line with my often stated definition of Astronomy, and how it seems to include virtually all the other Philosophy subjects: History, Science, Physics, Biology, Language, Cosmology and Mythology, lets go to mythology and re- tell the story behind the Argo Constellation. Argo Navis (or simply Argo) used to be a very large constellation in the southern sky. It represented the ship The Argo Navis ship with the Argonauts on board used by the Argonauts in Greek mythology who, in the years before the Trojan War, accompanied Jason to Colchis (modern day Georgia) in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. The ship was named after its builder, Argus. Argo is the only one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy that is no longer officially recognised as a constellation. In 1752, the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille subdivided it into Carina (the keel, or the hull, of the ship), Puppis (the poop deck), and Vela (the sails). The constellation Pyxis (the mariner's compass) occupies an area which in antiquity was considered part of Argo's mast (called Malus). The story goes that, when Jason was 20 years old, an oracle ordered him to head to the Iolcan court (modern city of Volos) where king Pelias was presiding over a sacrifice to Poseidon with several neighbouring kings in attendance. -

407 a Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , 351–353 Achromat

Index A Barnard 72 , 210–211 Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , Barnard, E.E. , 5, 389 351–353 Barnard’s loop , 5–8 Achromat , 365 Barred-ring spiral galaxy , 235 Adaptive optics (AO) , 377, 378 Barred spiral galaxy , 146, 263, 295, 345, 354 AGC S 373. See Abell Galaxy Cluster Bean Nebulae , 303–305 S 373 (AGC S 373) Bernes 145 , 132, 138, 139 Alnitak , 11 Bernes 157 , 224–226 Alpha Centauri , 129, 151 Beta Centauri , 134, 156 Angular diameter , 364 Beta Chamaeleontis , 269, 275 Antares , 129, 169, 195, 230 Beta Crucis , 137 Anteater Nebula , 184, 222–226 Beta Orionis , 18 Antennae galaxies , 114–115 Bias frames , 393, 398 Antlia , 104, 108, 116 Binning , 391, 392, 398, 404 Apochromat , 365 Black Arrow Cluster , 73, 93, 94 Apus , 240, 248 Blue Straggler Cluster , 169, 170 Aquarius , 339, 342 Bok, B. , 151 Ara , 163, 169, 181, 230 Bok Globules , 98, 216, 269 Arcminutes (arcmins) , 288, 383, 384 Box Nebula , 132, 147, 149 Arcseconds (arcsecs) , 364, 370, 371, 397 Bug Nebula , 184, 190, 192 Arditti, D. , 382 Butterfl y Cluster , 184, 204–205 Arp 245 , 105–106 Bypass (VSNR) , 34, 38, 42–44 AstroArt , 396, 406 Autoguider , 370, 371, 376, 377, 388, 389, 396 Autoguiding , 370, 376–378, 380, 388, 389 C Caldwell Catalogue , 241 Calibration frames , 392–394, 396, B 398–399 B 257 , 198 Camera cool down , 386–387 Barnard 33 , 11–14 Campbell, C.T. , 151 Barnard 47 , 195–197 Canes Venatici , 357 Barnard 51 , 195–197 Canis Major , 4, 17, 21 S. Chadwick and I. Cooper, Imaging the Southern Sky: An Amateur Astronomer’s Guide, 407 Patrick Moore’s Practical -

Interstellar Na I Absorption Towards Stars in the Region of the IRAS Vela Shell 1 3 M

4. Towards the Galactic Rotation Observatory and is now permanently in the rotation curve from 12 kpc to 15 kpc Curve Beyond 12 kpc with stalled at the 1.93-m telescope of the and answer the question: ELODIE Haute-Provence Observatory. This in "Does the dip of the rotation curve at strument possesses an automatic re 11 kpc exist and does the rotation curve A good knowledge of the outer rota duction programme called INTER determined from cepheids follow the tion curve is interesting since it reflects TACOS running on a SUN SPARC sta gas rotation curve?" the mass distribution of the Galaxy, and tion to achieve on-line data reductions The answer will give an important clue since it permits the kinematic distance and cross-correlations in order to get about the reality of a local non-axi determination of young disk objects. the radial velocity of the target stars symmetric motions and will permit to The rotation curve between 12 and minutes after the observation. The investigate a possible systematic error 16 kpc is not clearly defined by the ob cross-correlation algorithm used to find in the gas or cepheids distance scale servations as can be seen on Figure 3. the radial velocity of stars mimics the (due for instance to metal deficiency). Both the gas data and the cepheid data CORAVEl process, using a numerical clearly indicate a rotation velocity de mask instead of a physical one (for any References crease from RG) to R= 12 kpc, but then details, see Dubath et al. 1992). -

The Fundamentals of Stargazing Sky Tours South

The Fundamentals of Stargazing Sky Tours South 01 – The March Sky Copyright © 2014-2016 Mintaka Publishing Inc. www.CosmicPursuits.com -2- The Constellation Orion Let’s begin the tours of the deep-southern sky with the most famous and unmistakable constellation in the heavens, Orion, which will serve as a guide for other bright constellations in the southern late-summer sky. Head outdoors around 8 or 9 p.m. on an evening in early March, and turn towards the north. If you can’t find north, you can ask someone else, or get a small inexpensive compass, or use the GPS in your smartphone or tablet. But you need to face at least generally northward before you can proceed. You will also need a good unobstructed view of the sky in the north, so you may need to get away from structures and trees and so on. The bright stars of the constellation Orion (in this map, south is up and east is to the right) And bring a pair of binoculars if you have them, though they are not necessary for this tour. Fundamentals of Stargazing -3- Now that you’re facing north with a good view of a clear sky, make a 1/8th of a turn to your left. Now you are facing northwest, more or less. Turn your gaze upward about halfway to the point directly overhead. Look for three bright stars in a tidy line. They span a patch of sky about as wide as your three middle fingers held at arm’s length. This is the “belt” of the constellation Orion. -

The Radio Spectral Index of the Vela Supernova Remnant

A&A 372, 636–643 (2001) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20010509 & c ESO 2001 Astrophysics The radio spectral index of the Vela supernova remnant H. Alvarez1, J. Aparici1,J.May1,andP.Reich2 1 Departamento de Astronom´ıa, Universidad de Chile, Casilla 36-D, Santiago, Chile 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany Received 25 October 2000 / Accepted 9 March 2001 Abstract. We have calculated the integrated flux densities of the different components of the Vela SNR between 30 and 8400 MHz. The calculations were done using the original brightness temperature maps found in the literature, a uniform criterion to select the background temperature, and a unique method to compute the integrated flux density. We have succeeded in obtaining separately, and for the first time, the spectrum of Vela Y and Vela Z. The index of the flux density spectrum of Vela X,VelaY and Vela Z are −0.39, −0.70 and −0.81, respectively. We also present a map of brightness temperature spectral index over the region, between 408 and 2417 MHz. This shows a circular structure in which the spectrum steepens from the centre (Vela X) towards the periphery (Vela Y and Vela Z). X-ray observations show also a circular structure. We compare our spectral indices with those previously published. Key words. ISM: supernova remnants – ISM: Vela X – radio continuum: ISM 1. Introduction between the indices of X and YZ(α ∼−0.35) so that the whole Vela SNR belongs to the shell type. Weiler et al., Radio continuum maps of the Vela SNR area show a com- on the other hand, sustain that YZ has a spectrum con- plex structure. -

General Catalogue of Stars for 1860, Fan. 1

T H E C A P E C A T A L O G U E 1 1 ST ARS 5 9 , D ED UC ED FROM OBSERVATIONS AT T HE R YAL BSERV AT RY C APE O F G O D H PE O O O , O O , 1 8 6 T o 1 8 1 5 6 , RED UC ED TO THE EPOC H UN DER T HE SUPE RIN T EN DRN C R O ? E. S T O N E M . A J , ., ' (L AT E rnww o r mum s couzcz, ca umuncz), ’ HER MAJEST Y S AST RO NO MER AT T HE CAPE. PUBL B HED Br ORD ER OF THE BOARD O F EV OBEDIENC E TO HER M EWS C OMMJND . C APE T OWN O N C O . 8: 0 ST G E O G E S - ST R E E . SA U L SO L O M , 4 9 5 , . R T 1 873 . IN T R O D UC T I O N T O T HE A AL O G U E O F 1 1 5 ST A RS C A PE C T 9 , FO R T HE EPO C H 1 860. O r o f H was a n The Royal bservato y, Cape Good ope, established by in 1 820 O 20. O rder Council, dated , ctober The leading idea was to fi O r H fo r establish a rst class bservato y in the Southern emisphere, work o f a similar character to that o f the Greenwich O bservatory in the Northern Hemisphere. -

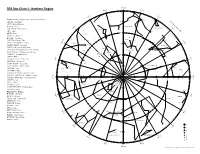

SFA Star Chart 1

Nov 20 SFA Star Chart 1 - Northern Region 0h Dec 6 Nov 5 h 23 30º 1 h d Dec 21 h p Oct 21h s b 2 h 22 ANDROMEDA - Daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia Mirach Local Meridian for 8 PM q m ANTLIA - Air Pumpe p 40º APUS - Bird of Paradise n o i b g AQUILA - Eagle k ANDROMEDA Jan 5 u TRIANGULUM AQUARIUS - Water Carrier Oct 6 h z 3 21 LACERTA l h ARA - Altar j g ARIES - Ram 50º AURIGA - Charioteer e a BOOTES - Herdsman j r Schedar b CAELUM - Graving Tool x b a Algol Jan 20 b o CAMELOPARDALIS - Giraffe h Caph q 4 Sep 20 CYGNUS k h 20 g a 60º z CAPRICORNUS - Sea Goat Deneb z g PERSEUS d t x CARINA - Keel of the Ship Argo k i n h m a s CASSIOPEIA - Ethiopian Queen on a Throne c h CASSIOPEIA g Mirfak d e i CENTAURUS - Half horse and half man CEPHEUS e CEPHEUS - Ethiopian King Alderamin a d 70º CETUS - Whale h l m Feb 5 5 CHAMAELEON - Chameleon h i g h 19 Sep 5 i CIRCINUS - Compasses b g z d k e CANIS MAJOR - Larger Dog b r z CAMELOPARDALIS 7 h CANIS MINOR - Smaller Dog e 80º g a e a Capella CANCER - Crab LYRA Vega d a k AURIGA COLUMBA - Dove t b COMA BERENICES - Berenice's Hair Aug 21 j Feb 20 CORONA AUSTRALIS - Southern Crown Eltanin c Polaris 18 a d 6 d h CORONA BOREALIS - Northern Crown h q g x b q 30º 30º 80º 80º 40º 70º 50º 60º 60º 70º 50º CRATER - Cup 40º i e CRUX - Cross n z b Rastaban h URSA CORVUS - Crow z r MINOR CANES VENATICI - Hunting Dogs p 80º b CYGNUS - Swan h g q DELPHINUS - Dolphin Kocab Aug 6 e 17 DORADO - Goldfish q h h h DRACO o 7 DRACO - Dragon s GEMINI t t Mar 7 EQUULEUS - Little Horse HERCULES LYNX z i a ERIDANUS - River j -

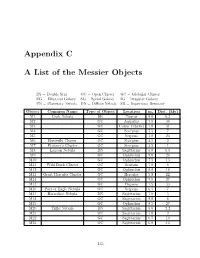

Appendix C a List of the Messier Objects

Appendix C A List of the Messier Objects DS=DoubleStar OC=OpenCluster GC=GlobularCluster EG = Elliptical Galaxy SG = Spiral Galaxy IG = Irregular Galaxy PN = Planetary Nebula DN = Diffuse Nebula SR = Supernova Remnant Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M1 Crab Nebula SR Taurus 9.0 6.3 M2 GC Aquarius 7.5 36 M3 GC Canes Venatici 7.0 31 M4 GC Scorpius 7.5 7 M5 GC Serpens 7.0 23 M6 Butterfly Cluster OC Scorpius 4.5 2 M7 Ptolemy’s Cluster OC Scorpius 3.5 1 M8 Lagoon Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 6.5 M9 GC Ophiuchus 9.0 26 M10 GC Ophiuchus 7.5 13 M11 Wild Duck Cluster OC Scutum 7.0 6 M12 GC Ophiuchus 8.0 18 M13 Great Hercules Cluster GC Hercules 5.8 22 M14 GC Ophiuchus 9.5 27 M15 GC Pegasus 7.5 33 M16 Part of Eagle Nebula OC Serpens 6.5 7 M17 Horseshoe Nebula DN Sagittarius 7.0 5 M18 OC Sagittarius 8.0 6 M19 GC Ophiuchus 8.5 27 M20 Trifid Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 2.2 M21 OC Sagittarius 7.0 3 M22 GC Sagittarius 6.5 10 M23 OC Sagittarius 6.0 4.5 135 Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M24 Milky Way Patch Star cloud Sagittarius 11.5 10 M25 OC Sagittarius 4.9 2 M26 OC Scutum 9.5 5 M27 Dumbbell Nebula PN Vulpecula 7.5 1.25 M28 GC Sagittarius 8.5 18 M29 OC Cygnus 9.0 7.2 M30 GC Capricornus 8.5 25 M31 Andromeda Galaxy SG Andromeda 3.5 2500 M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 EG Andromeda 10.0 2900 M33 Triangulum Galaxy SG Triangulum 7.0 2590 M34 OC Perseus 6.0 1.4 M35 OC Gemini 5.5 2.8 M36 OC Auriga 6.5 4.1 M37 OC Auriga 6.0 4.6 M38 OC Auriga 7.0 4.2 M39 OC Cygnus 5.5 0.3 M40 Winnecke 4 DS Ursa Major 9.0 M41 OC Canis -

Remote Video Astronomy Group MECATX Sky Tour January 2017

Remote Video Astronomy Group MECATX Sky Tour January 2017 (1) Canis Major (CANE-iss MAY-jer), the Great Dog - January 2 (2) Gemini (JEM-uh-nye), the Twins - January 5 (3) Monoceros (muh-NAH-ser-us), the Unicorn -January 5 (4) Puppis (PUP-iss), the Stern - January 8 (5) Canis Minor (CANE-iss MY-ner), the Lesser Dog - January 14 (6) Volans (VOH-lanz), the Flying Fish - January 18 (7) Lynx (LINKS), the Lynx - January 19 (8) Cancer (CAN-ser), the Crab - January 30 (9) Carina (cuh-REE-nuh), the Keel - January 31 MECATX RVA January 2017 - www.mecatx.ning.com – Youtube – MECATX – www.ustream.tv – dfkott Revised by: Samantha Salvador 12.28.2016 January 2 Canis Major (CANE-iss MAY-jer), the Great Dog CMa, Canis Majoris (CANE-iss muh-JOR-iss) MECATX RVA January 2017 - www.mecatx.ning.com – Youtube – MECATX – www.ustream.tv – dfkott 1 Canis Major Meaning: The Greater Dog Pronunciation: kay' niss may' jor Abbreviation: CMa Possessive form: Canis Majoris (kay' niss muh jor' iss) Asterisms: The Heavenly G, The Winter Octagon, The Winter Oval, The Winter Triangle Bordering constellations: Columba, Lepus, Monoceros, Puppis Overall brightness: 14.733 (6) Central point: RA = 6h47m Dec.= -22° Directional extremes: N = -11° S = -33° E = 7h26m W = 6h09m Messier objects: M41 Meteor showers: none Midnight culmination date: 2 Jan Bright stars: cx (1), (22), 8 (35), 3 (45),,q (86),(173), 02 (174) Named stars: Adhara (s), Aludra (i), Canicula (a), Furud (c), Mirzam (3), Muliphain (y), Sirius (cx), Wezen (ö) Near stars: a CMa A-B (6) Size: 380.11 square degrees (0.921% of the sky) Rank in size: 43 Solar conjunction date: 4 Jul Visibility: completely visible from latitudes: S of +57° completely invisible from latitudes: N of +79° Visible stars: (number of stars brighter than magnitude 5.5): 56 Interesting facts: (1) Sirius (a CMa) has the brightest apparent magnitude of any star in the nighttime sky.