Interstellar Na I Absorption Towards Stars in the Region of the IRAS Vela Shell 1 3 M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eclipse Newsletter

ECLIPSE NEWSLETTER The Eclipse Newsletter is dedicated to increasing the knowledge of Astronomy, Astrophysics, Cosmology and related subjects. VOLUMN 2 NUMBER 1 JANUARY – FEBRUARY 2018 PLEASE SEND ALL PHOTOS, QUESTIONS AND REQUST FOR ARTICLES TO [email protected] 1 MCAO PUBLIC NIGHTS AND FAMILY NIGHTS. The general public and MCAO members are invited to visit the Observatory on select Monday evenings at 8PM for Public Night programs. These programs include discussions and illustrated talks on astronomy, planetarium programs and offer the opportunity to view the planets, moon and other objects through the telescope, weather permitting. Due to limited parking and seating at the observatory, admission is by reservation only. Public Night attendance is limited to adults and students 5th grade and above. If you are interested in making reservations for a public night, you can contact us by calling 302-654- 6407 between the hours of 9 am and 1 pm Monday through Friday. Or you can email us any time at [email protected] or [email protected]. The public nights will be presented even if the weather does not permit observation through the telescope. The admission fees are $3 for adults and $2 for children. There is no admission cost for MCAO members, but reservations are still required. If you are interested in becoming a MCAO member, please see the link for membership. We also offer family memberships. Family Nights are scheduled from late spring to early fall on Friday nights at 8:30PM. These programs are opportunities for families with younger children to see and learn about astronomy by looking at and enjoying the sky and its wonders. -

Several Figures Have Been Removed from This Version See Complete Version At

Several figures have been removed from this version See complete version at http://www.astro.psu.edu/mystix Accepted for Astrophysical Journal Supplements, August 2013 Overview of the Massive Young Star-Forming Complex Study in Infrared and X-ray (MYStIX) Project Eric D. Feigelson∗1,2, Leisa K. Townsley1 , Patrick S. Broos 1, Heather A. Busk1 , Konstantin V. Getman1 , Robert King3, Michael A. Kuhn1 , Tim Naylor3 , Matthew Povich1,4 , Adrian Baddeley5,6 , Matthew Bate3, Remy Indebetouw7 , Kevin Luhman1,2 , Mark McCaughrean8 , 9 10 10 5 10 Julian Pittard , Ralph Pudritz , Alison Sills , Yong Song , James Wadsley ABSTRACT MYStIX (Massive Young Star-Forming Complex Study in Infrared and X- ray) seeks to characterize 20 OB-dominated young clusters and their environs at distances d ≤ 4 kpc using imaging detectors on the Chandra X-ray Obser- vatory, Spitzer Space Telescope, and the United Kingdom InfraRed Telescope. The observational goals are to construct catalogs of star-forming complex stel- lar members with well-defined criteria, and maps of nebular gas (particularly of * [email protected] 1 Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Pennsylvania State University, 525 Davey Laboratory, Uni- versity Park PA 16802 2 Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds, Penn State University, 525 Davey Laboratory, University Park PA 16802 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Exeter, Stocker Road, Exeter, Devon, EX4 4SB, UK 4 Department of Physics and Astronomy, California State Polytechnic University, 3801 West Temple Ave, Pomona, CA 91768 5 Mathematics, Informatics and Statistics, CSIRO, Underwood Avenue, Floreat WA 6014, Australia 6 School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley WA 6009, Australia 7 Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia, P.O. -

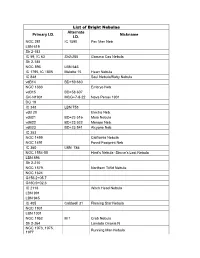

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Interstellar Reddening Towards Six Small Areas in Puppis-Vela⋆⋆⋆

A&A 543, A39 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201219007 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Interstellar reddening towards six small areas in Puppis-Vela, G. A. P. Franco Departamento de Física – ICEx – UFMG, Caixa Postal 702, 30.123-970 – Belo Horizonte – MG, Brazil e-mail: [email protected] Received 9 February 2012 / Accepted 1 May 2012 ABSTRACT Context. The line-of-sight towards Puppis-Vela contains some of the most interesting and elusive objects in the solar neighbourhood, including the Gum nebula, the IRAS Vela shell, the Vela SNR, and dozens of cometary globules. Aims. We investigate the distribution of the interstellar dust towards six small volumes of the sky in the region of the Gum nebula. Methods. New high-quality four-colour uvby and Hβ Strömgren photometry obtained for 352 stars in six selected areas of Kapteyn and complemented with data obtained in a previous investigation for two of these areas, were used to estimate the colour excess and distance to these objects. The obtained colour excess versus distance diagrams, complemented with other information, when available, were analysed in order to infer the properties of the interstellar medium permeating the observed volumes. Results. On the basis of the overall standard deviation in the photometric measurements, we estimate that colour excesses and distances are determined with an accuracy of 0m. 010 and better than 30%, respectively, for a sample of 520 stars. A comparison with 37 stars in common with the new Hipparcos catalogue attests to the high quality of the photometric distance determination. The obtained colour excess versus distance diagrams testify to the low density volume towards the observed lines-of-sight. -

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to Early Stellar Evolution and Molecular Clouds

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to early stellar evolution and molecular clouds No. 147 — 11 January 2005 Editor: Bo Reipurth ([email protected]) Abstracts of recently accepted papers Constraints on the ionizing flux emitted by T Tauri stars R.D. Alexander, C.J. Clarke & J.E. Pringle Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0HA, UK E-mail contact: [email protected] We present the results of an analysis of ultraviolet observations of T Tauri Stars (TTS). By analysing emission measures taken from the literature we derive rates of ionizing photons from the chromospheres of 5 classical TTS in the range ∼ 1041–1044 photons s−1, although these values are subject to large uncertainties. We propose that the He ii/C iv line ratio can be used as a reddening-independent indicator of the hardness of the ultraviolet spectrum emitted by TTS. By studying this line ratio in a much larger sample of objects we find evidence for an ionizing flux which does not decrease, and may even increase, as TTS evolve. This implies that a significant fraction of the ionizing flux from TTS is not powered by the accretion of disc material onto the central object, and we discuss the significance of this result and its implications for models of disc evolution. The presence of a significant ionizing flux in the later stages of circumstellar disc evolution provides an important new constraint on disc photoevaporation models. Accepted by MNRAS. Preprint available at http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/∼rda/publications.html or astro-ph/0501100 Laboratory and space spectroscopy of DCO+ Paola Caselli1 and Luca Dore2 1 INAF - Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. -

407 a Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , 351–353 Achromat

Index A Barnard 72 , 210–211 Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , Barnard, E.E. , 5, 389 351–353 Barnard’s loop , 5–8 Achromat , 365 Barred-ring spiral galaxy , 235 Adaptive optics (AO) , 377, 378 Barred spiral galaxy , 146, 263, 295, 345, 354 AGC S 373. See Abell Galaxy Cluster Bean Nebulae , 303–305 S 373 (AGC S 373) Bernes 145 , 132, 138, 139 Alnitak , 11 Bernes 157 , 224–226 Alpha Centauri , 129, 151 Beta Centauri , 134, 156 Angular diameter , 364 Beta Chamaeleontis , 269, 275 Antares , 129, 169, 195, 230 Beta Crucis , 137 Anteater Nebula , 184, 222–226 Beta Orionis , 18 Antennae galaxies , 114–115 Bias frames , 393, 398 Antlia , 104, 108, 116 Binning , 391, 392, 398, 404 Apochromat , 365 Black Arrow Cluster , 73, 93, 94 Apus , 240, 248 Blue Straggler Cluster , 169, 170 Aquarius , 339, 342 Bok, B. , 151 Ara , 163, 169, 181, 230 Bok Globules , 98, 216, 269 Arcminutes (arcmins) , 288, 383, 384 Box Nebula , 132, 147, 149 Arcseconds (arcsecs) , 364, 370, 371, 397 Bug Nebula , 184, 190, 192 Arditti, D. , 382 Butterfl y Cluster , 184, 204–205 Arp 245 , 105–106 Bypass (VSNR) , 34, 38, 42–44 AstroArt , 396, 406 Autoguider , 370, 371, 376, 377, 388, 389, 396 Autoguiding , 370, 376–378, 380, 388, 389 C Caldwell Catalogue , 241 Calibration frames , 392–394, 396, B 398–399 B 257 , 198 Camera cool down , 386–387 Barnard 33 , 11–14 Campbell, C.T. , 151 Barnard 47 , 195–197 Canes Venatici , 357 Barnard 51 , 195–197 Canis Major , 4, 17, 21 S. Chadwick and I. Cooper, Imaging the Southern Sky: An Amateur Astronomer’s Guide, 407 Patrick Moore’s Practical -

The Radio Spectral Index of the Vela Supernova Remnant

A&A 372, 636–643 (2001) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20010509 & c ESO 2001 Astrophysics The radio spectral index of the Vela supernova remnant H. Alvarez1, J. Aparici1,J.May1,andP.Reich2 1 Departamento de Astronom´ıa, Universidad de Chile, Casilla 36-D, Santiago, Chile 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany Received 25 October 2000 / Accepted 9 March 2001 Abstract. We have calculated the integrated flux densities of the different components of the Vela SNR between 30 and 8400 MHz. The calculations were done using the original brightness temperature maps found in the literature, a uniform criterion to select the background temperature, and a unique method to compute the integrated flux density. We have succeeded in obtaining separately, and for the first time, the spectrum of Vela Y and Vela Z. The index of the flux density spectrum of Vela X,VelaY and Vela Z are −0.39, −0.70 and −0.81, respectively. We also present a map of brightness temperature spectral index over the region, between 408 and 2417 MHz. This shows a circular structure in which the spectrum steepens from the centre (Vela X) towards the periphery (Vela Y and Vela Z). X-ray observations show also a circular structure. We compare our spectral indices with those previously published. Key words. ISM: supernova remnants – ISM: Vela X – radio continuum: ISM 1. Introduction between the indices of X and YZ(α ∼−0.35) so that the whole Vela SNR belongs to the shell type. Weiler et al., Radio continuum maps of the Vela SNR area show a com- on the other hand, sustain that YZ has a spectrum con- plex structure. -

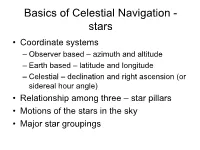

Azimuth and Altitude – Earth Based – Latitude and Longitude – Celestial

Basics of Celestial Navigation - stars • Coordinate systems – Observer based – azimuth and altitude – Earth based – latitude and longitude – Celestial – declination and right ascension (or sidereal hour angle) • Relationship among three – star pillars • Motions of the stars in the sky • Major star groupings Comments on coordinate systems • All three are basically ways of describing locations on a sphere – inherently two dimensional – Requires two parameters (e.g. latitude and longitude) • Reality – three dimensionality – Height of observer – Oblateness of earth, mountains – Stars at different distances (parallax) • What you see in the sky depends on – Date of year – Time – Latitude – Longitude – Which is how we can use the stars to navigate!! Altitude-Azimuth coordinate system Based on what an observer sees in the sky. Zenith = point directly above the observer (90o) Nadir = point directly below the observer (-90o) – can’t be seen Horizon = plane (0o) Altitude = angle above the horizon to an object (star, sun, etc) (range = 0o to 90o) Azimuth = angle from true north (clockwise) to the perpendicular arc from star to horizon (range = 0o to 360o) Note: lines of azimuth converge at zenith The arc in the sky from azimuth of 0o to 180o is called the local meridian Point of view of the observer Latitude Latitude – angle from the equator (0o) north (positive) or south (negative) to a point on the earth – (range = 90o = north pole to – 90o = south pole). 1 minute of latitude is always = 1 nautical mile (1.151 statute miles) Note: It’s more common to express Latitude as 26oS or 42oN Longitude Longitude = angle from the prime meridian (=0o) parallel to the equator to a point on earth (range = -180o to 0 to +180o) East of PM = positive, West of PM is negative. -

Astronomical Coordinate Systems

Appendix 1 Astronomical Coordinate Systems A basic requirement for studying the heavens is being able to determine where in the sky things are located. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each sys- tem uses a coordinate grid projected on the celestial sphere, which is similar to the geographic coor- dinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth’s equator). Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The Equatorial Coordinate System The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the most closely related to the geographic coordinate system because they use the same funda- mental plane and poles. The projection of the Earth’s equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles onto the celestial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate sys- tems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth and rotates as the Earth does. The Equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but it’s really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec. for short). It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. -

B Stars Seen at High Resolution by XMM-Newton

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. paper c ESO 2018 April 16, 2018 B stars seen at high resolution by XMM-Newton⋆ Constantin Cazorla and Yaël Nazé⋆⋆ Groupe d’Astrophysique des Hautes Energies, STAR, Université de Liège, Quartier Agora (B5c, Institut d’Astrophysique et de Géo- physique), Allée du 6 Août 19c, B-4000 Sart Tilman, Liège, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] April 16, 2018 ABSTRACT We report on the properties of 11 early B stars observed with gratings on board XMM-Newton and Chandra, thereby doubling the number of B stars analysed at high resolution. The spectra typically appear soft, with temperatures of 0.2–0.6 keV, and moderately bright (log[LX/LBOL] ∼−7) with lower values for later type stars. In line with previous studies, we also find an absence of circumstellar absorption, negligible line broadening, no line shift, and formation radii in the range 2 – 7 R⋆. From the X-ray brightnesses, we derived the hot mass-loss rate for each of our targets and compared these values to predictions or values derived in the optical domain: in some cases, the hot fraction of the wind can be non-negligible. The derived X-ray abundances were compared to values obtained from the optical data, with a fair agreement found between them. Finally, half of the sample presents temporal variations, either in the long-term, short-term, or both. In particular, HD 44743 is found to be the second example of an X-ray pulsator, and we detect a flare-like activity in the binary HD 79351, which also displays a high-energy tail and one of the brightest X-ray emissions in the sample. -

THE APPEARANCE of the GUM NEBULA Bart J. Bok Steward

THE APPEARANCE OF THE GUM NEBULA Bart J. Bok Steward Observatory University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 According to Brandt et al. (1971), the center of the Gum Nebula is at a dis- tance of 460 parsecs from the Sun. The outer dimensions quoted by these authors are 40° x 90 ° , and they suspect that the inner boundary of the emission region lies at about 100 parsecs from the Sun. They assign a radius of 360 parsecs to the nebula, which they suspect of being slightly flattened, with the huge volume of 1.4 x 1063 cm3 ! Obviously, tremendous amounts of energy must have been available to ionize so large a volume. Brandt estimates that 1052 erg of energy were-required to do the job. The Wolf-Rayet star y2 Velorum and the 05f star 5 Puppis would obviously not be equal to this task. However, I wish to challenge the distances and dimensions quoted by Brandt et al. First of all, I question the assumption that the Gum Nebula complex is as large as suggested by Brandt et al. The quoted dimensions of 40° x 90° seem like gross overestimates, since they are based on the assumption that some minor outlying patches of nebulosity fix the outer boundary of the region of ionization; 350 seems like a more reasonable value for the diameter of the complex. We should stress the non-homogeneous appearance of the nebular complex. There is a region of brightest nebulosity centered upon y 2 Velorum, a WC8 star. It has an apparent diameter of 9° , to which would correspond a radius for the Str5 mgren sphere of ionization of about 50 parsecs at the esti- mated distance of 460 parsecs. -

![Arxiv:1709.07265V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 21 Sep 2017 an Der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany E-Mail: Jstorm@Aip.De 2 Smitha Subramanian Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4549/arxiv-1709-07265v1-astro-ph-sr-21-sep-2017-an-der-sternwarte-16-14482-potsdam-germany-e-mail-jstorm-aip-de-2-smitha-subramanian-et-al-2324549.webp)

Arxiv:1709.07265V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 21 Sep 2017 an Der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Smitha Subramanian Et Al

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Young and Intermediate-age Distance Indicators Smitha Subramanian · Massimo Marengo · Anupam Bhardwaj · Yang Huang · Laura Inno · Akiharu Nakagawa · Jesper Storm Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract Distance measurements beyond geometrical and semi-geometrical meth- ods, rely mainly on standard candles. As the name suggests, these objects have known luminosities by virtue of their intrinsic proprieties and play a major role in our understanding of modern cosmology. The main caveats associated with standard candles are their absolute calibration, contamination of the sample from other sources and systematic uncertainties. The absolute calibration mainly de- S. Subramanian Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics Peking University, Beijing, China E-mail: [email protected] M. Marengo Iowa State University Department of Physics and Astronomy, Ames, IA, USA E-mail: [email protected] A. Bhardwaj European Southern Observatory 85748, Garching, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Yang Huang Department of Astronomy, Kavli Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, Peking University, Beijing, China E-mail: [email protected] L. Inno Max-Planck-Institut f¨urAstronomy 69117, Heidelberg, Germany E-mail: [email protected] A. Nakagawa Kagoshima University, Faculty of Science Korimoto 1-1-35, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan E-mail: [email protected] J. Storm Leibniz-Institut f¨urAstrophysik Potsdam (AIP) arXiv:1709.07265v1 [astro-ph.SR] 21 Sep 2017 An der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany E-mail: [email protected] 2 Smitha Subramanian et al. pends on their chemical composition and age. To understand the impact of these effects on the distance scale, it is essential to develop methods based on differ- ent sample of standard candles.