International Journal of Applied Science and Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nairobi Attack and Al-Shabab's Media Strategy

OCTOBER 2013 . VOL 6 . ISSUE 10 Contents The Nairobi Attack and FEATURE ARTICLE 1 The Nairobi Attack and Al-Shabab’s Al-Shabab’s Media Strategy Media Strategy By Christopher Anzalone By Christopher Anzalone REPORTS 6 The Dutch Foreign Fighter Contingent in Syria By Samar Batrawi 10 Jordanian Jihadists Active in Syria By Suha Philip Ma’ayeh 13 The Islamic Movement and Iranian Intelligence Activities in Nigeria By Jacob Zenn 19 Kirkuk’s Multidimensional Security Crisis By Derek Henry Flood 22 The Battle for Syria’s Al-Hasakah Province By Nicholas A. Heras 25 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts Kenyan soldiers take positions outside the Westgate Mall in Nairobi on September 21, 2013. - Photo by Jeff Angote/Getty Images fter carrying out a bold Godane. The attack also followed a attack inside the upscale year in which al-Shabab lost control Westgate Mall in Nairobi in of significant amounts of territory in September 2013, the Somali Somalia, most importantly major urban Amilitant group al-Shabab succeeded in and economic centers such as the cities recapturing the media spotlight. This of Baidoa and Kismayo. was in large part due to the nature of the attack, its duration, the difficulty This article examines al-Shabab’s About the CTC Sentinel in resecuring the mall, the number of media strategy during and immediately The Combating Terrorism Center is an casualties, and al-Shabab’s aggressive after the Westgate Mall attack, both independent educational and research media campaign during and immediately via micro-blogging on Twitter through institution based in the Department of Social after the attack.1 its various accounts as well as more Sciences at the United States Military Academy, traditional media formats such as West Point. -

166 Other Information

Other information 167 Management team 176 Contact information 171 Branch network Stanbic IBTC Bank I Annual report 2011 166 Management team Kunle Adedeji Adesola Adegbesan Jumoke Adejumobi Finance Global Markets Financial Institutions Jadesola Ademuliyi Adenrele Adesina Bayo Adesina Project Governance Research Public Sector Ayo Adio Aisha Ahmad Folasope Aiyesimoju PBB, Distribution Private Clients and HNIs Financial Advisory 167 Stanbic IBTC Bank I Annual report 2011 Oyinda Akinyemi Shuiabu Audu Leye Babatunde Equity Capital Markets Stanbic IBTC Asset Management Information Technology Fatai Baruwa Kobby Bentsi-Enchil Mathys Buitendag Payment strategy Debt Capital Market Business Banking Olu Delano Steve Elusope Eric Fajemisin Leverage and Acquisition Finance Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Other information Stanbic IBTC Bank I Annual report 2011 168 Management team Samir Gadio Olufunke Isichei Busola Jejelowo Research Customer Experience Stanbic IBTC Stockbrokers Dele Kuti Thabo Makoko Binta Max-Gbinije Energy Transaction Products and Services Stanbic IBTC Trustees Samuel Ochecho Olumide Oyetan Akeem Oyewale Global Markets Stanbic IBTC Asset Management Global Markets 169 Stanbic IBTC Bank I Annual report 2011 Anne Rinu Yewande Sadiku Babayo Saidu Premises and Projects Investment Banking Non-interest Banking Segun Sanni Alubani Sibanda John Smit Investor Services Corporate Banking Products and Strategy Dele Sotubo Delein Van Schallkwyk Jaco Viljoen Stanbic IBTC Stockbrokers Operations Personal Markets Other information Stanbic IBTC Bank I Annual report 2011 170 Branch network FCT Abuja region Lagos Island region Lagos Mainland region 1. Ahmadu Bello Way branch, 1. Adetokunbo Ademola branch 1. Agege branch Plot 1049, Ahmadu Bello Way, No. 76, Adetokunbo Ademola street, 173, Old Abeokuta motor road, Area 11, Garki, Abuja Victoria Island, Lagos Agege, Lagos 2. -

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa? DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS BUT NO DEMOCRACY Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos cahiers & conférences travaux & recherches les études The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non- profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. The Sub-Saharian Africa Program is supported by: Translated by: Henry Kenrick, in collaboration with the author © Droits exclusivement réservés – Ifri – Paris, 2010 ISBN: 978-2-86592-709-8 Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27 rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – France 1000 Bruxelles – Belgique Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tél. : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Internet Website : Ifri.org Summary Sub-Saharan African hopes of democratization raised by the end of the Cold War and the decline in the number of single party states are giving way to disillusionment. -

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM and NATION

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM AND NATION-BUILDING IN NIGERIA, 1970-1992 Submitted for examination for the degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 1993 UMI Number: U615538 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615538 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 V - x \ - 1^0 r La 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the relationship between ethnicity and nation-building and nationalism in Nigeria. It is argued that ethnicity is not necessarily incompatible with nationalism and nation-building. Ethnicity and nationalism both play a role in nation-state formation. They are each functional to political stability and, therefore, to civil peace and to the ability of individual Nigerians to pursue their non-political goals. Ethnicity is functional to political stability because it provides the basis for political socialization and for popular allegiance to political actors. It provides the framework within which patronage is institutionalized and related to traditional forms of welfare within a state which is itself unable to provide such benefits to its subjects. -

Newsletter Igbo Studies Association

NEWSLETTER IGBO STUDIES ASSOCIATION VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 ISSN: 2375-9720 COVER PHOTO CREDIT INCHSERVICES.COM PAGE 1 VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 EDITORIAL WELCOME TO THE FIRST EDITION OF ISA NEWS! November 2014 Dear Members, I am delighted to introduce the first edition of ISA Newsletter! I hope your semester is going well. I wish you the best for the rest of the academic year! I hope that you will enjoy this maiden issue of ISA Newsletter, which aims to keep you abreast of important issue and events concerning the association as well as our members. The current issue includes interesting articles, research reports and other activities by our Chima J Korieh, PhD members. The success of the newsletter will depend on your contributions in the forms of President, Igbo Studies Association short articles and commentaries. We will also appreciate your comments and suggestions for future issues. The ISA executive is proud to announce that a committee has been set up to work out the modalities for the establishment of an ISA book prize/award. Dr Raphael Njoku is leading the committee and we expect that the initiative will be approved at the next annual general meeting. The 13th Annual Meeting of the ISA taking place at Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is only six months away and preparations are ongoing to ensure that we have an exciting meet! We can’t wait to see you all in Milwaukee in April. This is an opportunity to submit an abstract and to participate in next year’s conference. ISA is as strong as its membership, so please remember to renew your membership and to register for the conference, if you have not already done so! Finally, we would like to congratulate the newest members of the ISA Executive who were elected at the last annual general meeting in Chicago. -

Policy Levers in Nigeria

CRISE Policy Context Paper 2, December 2003 Policy Levers in Nigeria By Ukoha Ukiwo Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, CRISE Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Executive Summary This paper identifies some prospective policy levers for the CRISE programme in Nigeria. It is divided into two parts. The first part is a narrative of the political history of Nigeria which provides the backdrop for the policy environment. In the second part, an attempt is made to identify the relevant policy actors in the country. Understanding the Policy Environment in Nigeria The policy environment in Nigeria is a complex one that is underlined by its chequered political history. Some features of this political history deserve some attention here. First, despite the fact that prior to its independence Nigeria was considered as a natural democracy because of its plurality and westernized political elites, it has been difficult for the country to sustain democratic politics. The military has held power for almost 28 years out of 43 years since Nigeria became independent. The result is that the civic culture required for democratic politics is largely absent both among the political class and the citizenry. Politics is construed as a zero sum game in which the winner takes all. In these circumstances, political competition has been marked by political violence and abandonment of legitimacy norms. The implication of this for the policy environment is that formal institutions and rules are often subverted leading to the marginalization of formal actors. During the military period, the military political class incorporated bureaucrats and traditional rulers in the process of governance. -

Nigeria: the Challenge of Military Reform

Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform Africa Report N°237 | 6 June 2016 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Long Decline .............................................................................................................. 3 A. The Legacy of Military Rule ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Military under Democracy: Failed Promises of Reform .................................... 4 1. The Obasanjo years .............................................................................................. 4 2. The Yar’Adua and Jonathan years ....................................................................... 7 3. The military’s self-driven attempts at reform ...................................................... 8 III. Dimensions of Distress ..................................................................................................... 9 A. The Problems of Leadership and Civilian Oversight ................................................ -

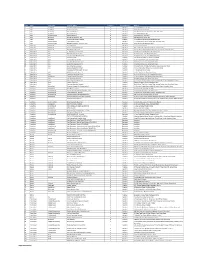

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

International Journal of Contemporary Social

INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF JOURNAL CONTEMPORARY OF CONTEMPORARY Vol. 1:1, 2013 SOCIAL SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH www.iscprce.org/ ijcssr SOCIAL SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH VOL. 1:1, 2013 www.iscprce.org/ ijcssr RELIGION, POLITICS AND THE STATE IN NIGERIA, 1985- 1995 Dr. Etim E. Okon Senior Lecturer Department of Religious and Cultural Studies University of Calabar Calabar, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Phone: +2348038025231 ABSTRACT This paper examines critically the religious dimension of political decisions and policies in the Babangida era. It is obvious that religion was manipulated in the Babangida era as a major influence and determinant of public policy. The negative impact of the manipulation of religion for political purposes is still lingering in the horizon. Religion was not only bastardized, but was reasonably politicized and contaminated. Babangida used religion to obtain legitimacy and consolidate his grip on political power. KEYWORDS: Religion, Islam, politics, Nigeria, Babangida INTRODUCTION Religion is an indispensable factor in nation building. Historically, Christianity and Islam have contributed immensely to the socio-political development of Nigeria. Both religions, at one time and another have acted as harbingers of civilization and “… the fountain of morality in our social evolution” (Kalu, 1980:317, 318). Though exotic, from the point of view of origin, Islam and Christianity have so permeated the Nigerian culture and society, that they have unconsciously assumed the status of an indigenous faith in some communities. That is true of Islam in northern Nigeria and Christianity in the south. Majority of Nigerian people see themselves either as Christians or Muslims. An insignificant proportion identifies themselves as votaries of traditional religions. -

Herdsmen Terror in Nigeria: the Identity Question and Classification Dilemma

American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2020 American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-03, Issue-03, pp 10-25 March-2020 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access Herdsmen Terror In Nigeria: The Identity Question And Classification Dilemma PROF. CYRIL ANAELE Department Of History & Diplomatic Studies Salem University, Lokoja – Nigeria Phone: +23408068683303 *Corresponding Author: PROF. CYRIL ANAELE ABSTRACT:- Nigeria in recent years is a home to diversities of terror restricted to specific geo-political zones. Of all these terrors, non cuts across the country as that of the herdsmen. The herdsmen like invading Mongols leave deaths and destructions in their wake. Certainly and troubling too, is the government’s unwillingness to classify them as terrorist gang, but instead is dangling on classification dilemma. This too, has created identity question, on who actually are these herdsmen and their exact identity. Government has chosen to identify them as herdsmen and sees their killings as precipitated by conflict over land, between herders and farmers. The paper rejects government’s position that the herdsmen are not terrorists; and their activities as conflict over grazing land. To the contrary, the paper argues that the herdsmen are Fulani (in and outside Nigeria) hundred percent Muslim, and their terror fundamentally linked to causes beyond competition over land. It adopts the Samuel Huntington (1996) and Healy “Multiple Factor” theory for its theoretical framework. In methodology, it relies on primary and secondary data, using historical unit analysis for the presentation. The major findings of the study are, (i) the herdsmen are Fulani, (ii) their orchestrated violence across Nigeria is naked terrorism anxiously waiting to be listed as domestic terrorism before it morphoses into international terror (iii)the overall objective is Islamisation and Fulanisation of Nigeria. -

4.11 Nigeria Additional Services Contact List

4.11 Nigeria Additional Services Contact List Type of Company Loca Street / Physical Address Name Title Email Phone Number (office) Website Description of Service tion Services (s) Provided Telecomm Airtel Natio Plot L2 Banana Island, https://www.airtel. +234 802 150 0111, +234 http://www. mobile network unications Nigeria nal Foreshore Estate, Ikoyi, Lagos com.ng/contact_us 802 150 0121 africa.airtel. facilities, internet- provider State, com/wps network provider airtelpremier@ng. /wcm/connect and airtel.com /africarevamp telecommunicatio /Nigeria/ n services. Telecomm 9Mobile Natio Ropp House [email protected]. 08090000200 https://9mobil mobile network unications (previously nal Plot 1774 Adetokunbo ng e.com.ng facilities, internet- provider Estilat) Ademola Crescent Wuse 2, /home/ network provider Abuja and , FCT, telecommunicatio n services. Telecomm MTN Natio Churchgate towers, 5th Floor, https://mtnonline.com +234 80310180, +234 http://www. mobile network unications Nigeria nal Plot 30, Afribank street, /about-mtn/contact- 80310188 mtnonline. facilities, internet- provider Victoria Island, Lagos Stat us com network provider 80310180 and telecommunicatio n services Banking United Natio UBA House 57 Marina. P O www.ubagroup.com +234 7002255822 cfc@ubagrou Currency and Bank for nal Box 2406 Lagos, Nigeria p.com exchange,wire Financial Africa transfers, loans services and all other banking services Banking Zenith Natio Plot 84, Ajose Adeogun Street, https://www. zenithdirect@z Currency and Bank nal Victoria Island, Lagos. Nigeria zenithbank.com/ enithbank.com exchange, wire Financial + 234-1-2787000 transfers, loans services and all other banking services Banking First Bank Natio Samual Asabia House, 35 https://www. +234 1 4485500 firstcontact@fir Currency and of Nigeria nal Marina Lagos, Nigeria firstbanknigeria. -

Access Bank Branches Nationwide

LIST OF ACCESS BANK BRANCHES NATIONWIDE ABUJA Town Address Ademola Adetokunbo Plot 833, Ademola Adetokunbo Crescent, Wuse 2, Abuja. Aminu Kano Plot 1195, Aminu Kano Cresent, Wuse II, Abuja. Asokoro 48, Yakubu Gowon Crescent, Asokoro, Abuja. Garki Plot 1231, Cadastral Zone A03, Garki II District, Abuja. Kubwa Plot 59, Gado Nasko Road, Kubwa, Abuja. National Assembly National Assembly White House Basement, Abuja. Wuse Market 36, Doula Street, Zone 5, Wuse Market. Herbert Macaulay Plot 247, Herbert Macaulay Way Total House Building, Opposite NNPC Tower, Central Business District Abuja. ABIA STATE Town Address Aba 69, Azikiwe Road, Abia. Umuahia 6, Trading/Residential Area (Library Avenue). ADAMAWA STATE Town Address Yola 13/15, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola. AKWA IBOM STATE Town Address Uyo 21/23 Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom. ANAMBRA STATE Town Address Awka 1, Ajekwe Close, Off Enugu-Onitsha Express way, Awka. Nnewi Block 015, Zone 1, Edo-Ezemewi Road, Nnewi. Onitsha 6, New Market Road , Onitsha. BAUCHI STATE Town Address Bauchi 24, Murtala Mohammed Way, Bauchi. BAYELSA STATE Town Address Yenagoa Plot 3, Onopa Commercial Layout, Onopa, Yenagoa. BENUE STATE Town Address Makurdi 5, Ogiri Oko Road, GRA, Makurdi BORNO STATE Town Address Maiduguri Sir Kashim Ibrahim Way, Maiduguri. CROSS RIVER STATE Town Address Calabar 45, Muritala Mohammed Way, Calabar. Access Bank Cash Center Unicem Mfamosing, Calabar DELTA STATE Town Address Asaba 304, Nnebisi, Road, Asaba. Warri 57, Effurun/Sapele Road, Warri. EBONYI STATE Town Address Abakaliki 44, Ogoja Road, Abakaliki. EDO STATE Town Address Benin 45, Akpakpava Street, Benin City, Benin. Sapele Road 164, Opposite NPDC, Sapele Road.