The Evolution of Banking Regulation in India – a Retrospect on Some Aspects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Site, Telegram, Facebook, Instagram, Instamojo

Page 1 Follow us: Official Site, Telegram, Facebook, Instagram, Instamojo All SUPER Current Affairs Product Worth Rs 1200 @ 399/- ( DEAL Of The Year ) Page 2 Follow us: Official Site, Telegram, Facebook, Instagram, Instamojo SUPER Current Affairs MCQ PDF 3rd August 2021 By Dream Big Institution: (SUPER Current Affairs) © Copyright 2021 Q.World Sanskrit Day 2021 was celebrated on ___________. A) 3 August C) 5 August B) 4 August D) 6 August Answer - A Sanskrit Day is celebrated every year on Shraavana Poornima, which is the full moon day in the month of Shraavana in the Hindu calendar. In 2020, Sanskrit Day was celebrated on August 3, while in 2019 it was celebrated on 15 August. Sanskrit language is believed to be originated in India around 3,500 years ago. Q.Nikol Pashinyan has been re-appointed as the Prime Minister of which country? A) Ukraine C) Turkey B) Armenia D) Lebanon Answer - B Nikol Pashinyan has been re-appointed as Armenia’s Prime Minister by President Armen Sarkissian. Pashinyan was first appointed as the prime minister in 2018. About Armenia: Capital: Yerevan Currency: Armenian dram President: Armen Sargsyan Page 3 Follow us: Official Site, Telegram, Facebook, Instagram, Instamojo Q.Min Aung Hlaing has taken charge as the Prime Minister of which country? A) Bangladesh C) Thailand B) Laos D) Myanmar Answer - D The Chief of the Myanmar military, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing has taken over as the interim prime minister of the country on August 01, 2021. About Myanmar Capital: Naypyitaw; Currency: Kyat. NEWLY Elected -

State Bank of India

State Bank of India State Bank of India Type Public Traded as NSE: SBIN BSE: 500112 LSE: SBID BSE SENSEX Constituent Industry Banking, financial services Founded 1 July 1955 Headquarters Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Area served Worldwide Key people Pratip Chaudhuri (Chairman) Products Credit cards, consumer banking, corporate banking,finance and insurance,investment banking, mortgage loans, private banking, wealth management Revenue US$ 36.950 billion (2011) Profit US$ 3.202 billion (2011) Total assets US$ 359.237 billion (2011 Total equity US$ 20.854 billion (2011) Owner(s) Government of India Employees 292,215 (2012)[1] Website www.sbi.co.in State Bank of India (SBI) is a multinational banking and financial services company based in India. It is a government-owned corporation with its headquarters in Mumbai, Maharashtra. As of December 2012, it had assets of US$501 billion and 15,003 branches, including 157 foreign offices, making it the largest banking and financial services company in India by assets.[2] The bank traces its ancestry to British India, through the Imperial Bank of India, to the founding in 1806 of the Bank of Calcutta, making it the oldest commercial bank in the Indian Subcontinent. Bank of Madras merged into the other two presidency banks—Bank of Calcutta and Bank of Bombay—to form the Imperial Bank of India, which in turn became the State Bank of India. Government of Indianationalised the Imperial Bank of India in 1955, with Reserve Bank of India taking a 60% stake, and renamed it the State Bank of India. In 2008, the government took over the stake held by the Reserve Bank of India. -

Banking Laws in India

Course: CBIL-01 Banking Laws In India Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota 1 Course: CBIL-01 Banking Laws In India Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota 2 Course Development Committee CBIL-01 Chairman Prof. L. R. Gurjar Director (Academic) Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Convener and Members Convener Dr. Yogesh Sharma, Asso. Professor Prof. H.B. Nanadwana Department of Law Director, SOCE Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota External Members: 1. Prof. Satish C. Shastri 2. Prof. V.K. Sharma Dean, Faculty of law, MITS, Laxmangarh Deptt.of Law Sikar, and Ex. Dean, J.N.Vyas University, Jodhpur University of Rajasthan, Jaipur (Raj.) 3. Dr. M.L. Pitaliya 4. Prof. (Dr.) Shefali Yadav Ex. Dean, MDS University, Ajmer Professor & Dean - Law Principal, Govt. P.G.College, Chittorgarh (Raj.) Dr. Shakuntala Misra National Rehabilitation University, Lucknow 5. Dr Yogendra Srivastava, Asso. Prof. School of Law, Jagran Lakecity University, Bhopal Editing and Course Writing Editor: Course Writer: Dr. Yogesh Sharma Dr Visvas Chauhan Convener, Department of Law State P. G. Law College, Bhopal Vardhaman Mahaveer Open niversity, Kota Academic and Administrative Management Prof. Vinay Kumar Pathak Prof. L.R. Gurjar Vice-Chancellor Director (Academic) Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Prof. Karan Singh Dr. Anil Kumar Jain Director (MP&D) Additional Director (MP&D) Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Course Material Production Prof. Karan Singh Director (MP&D) Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Production 2015 ISBN- All right reserved no part of this book may be reproduced in any form by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the V.M. -

A Study on Customer Satisfaction of Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM)

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8 Issue-6, April 2019 A Study on Customer Satisfaction of Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM) Anjali R, Suresh A Abstract: After demonetization on November 8th, 2016, India saw an increased use of different internet payment systems for Mobile banking saw its growth during the period of 2009- money transfer through various devices. NPCI (National 2010 with improvement in mobile internet services across Payments Corporation India) launched Bharat interface for India. SMS based applications along with mobile Money (BHIM) an application run on UPI (Unified Payment application compatible with smartphones offered improved Interface) in December 2016 to cater the growing online payment banking services to the customers. Apart from the bank’s needs. The different modes of digital payments saw a drastic mobile applications other applications like BHIM, Paytm, change in usage in the last 2 years. Though technological Tez etc. offered provided enhanced features that lead to easy innovations brought in efficiency and security in transactions, access to banking services. In addition to this, The Reserve many are still unwilling to adopt and use it. Earlier studies Bank of India has given approval to 80 Banks to start mobile related to adoption, importance of internet banking and payment systems attributed it to some factors which are linked to security, banking services including applications. Bharat Interface for ease of use and satisfaction level of customers. The purpose of money (BHIM) was launched after demonetization by this study is to unfold some factors which have an influence on National Payments Corporation (NPCI) by Prime Minister the customer satisfaction of BHIM application. -

Download Free PDF Here

www.gradeup.co 1 | Page www.gradeup.co GK Tornado for IBPS PO Mains Exam -2017 Dear readers, This GK Tornado is a complete docket of important news and events that occurred in last 4.5 months (1st July–14th Nov 2017). Tornado is important and relevant for all competitive exams like Banking, Insurance, SSC and UPSC Exams. Banking & Financial Awareness 1. RBI keeps repo rate unchanged at 6% - On 4th October 2017, RBI in its fourth Bi-Monthly Monetary Policy Statement decided to keep the policy Repo rate unchanged at 6%. Therefore, the reverse repo rate under the LAF remains at 5.75 per cent, and the marginal standing facility (MSF) rate and the Bank Rate at 6.25 per cent. However, RBI cut the Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) by 0.5 percent to 19.5 percent. New Policy & Reserve Rates 1. Repo Rate 6% (unchanged) 2. Reverse Repo Rate 5.75% (unchanged) 3. CRR (Cash Reserve Ratio) 4.00% (unchanged) 4. SLR (Statutory Liquidity Ratio) 19.50% (changed) 5. MSF (Marginal Standing Facility) 6.25% (unchanged) 6. Bank Rate 6.25% (unchanged) 2. RBI sets up task force on Public Credit Registry financial transactions in different national (PCR) - The Reserve Bank of India constituted a 10- jurisdictions can be fully tracked. The first LEIs member ‘High Level Task Force on Public Credit were issued in December 2012. Registry (PCR) for India’. The task force will be headed ➢ Legal Entity Identifier India Limited (LEIL), a by YM Deosthalee, ex-CMD of L&T Finance Holdings. wholly-owned subsidiary of Clearing 3. -

Chennai District Origin of Chennai

DISTRICT PROFILE - 2017 CHENNAI DISTRICT ORIGIN OF CHENNAI Chennai, originally known as Madras Patnam, was located in the province of Tondaimandalam, an area lying between Pennar river of Nellore and the Pennar river of Cuddalore. The capital of the province was Kancheepuram.Tondaimandalam was ruled in the 2nd century A.D. by Tondaiman Ilam Tiraiyan, who was a representative of the Chola family at Kanchipuram. It is believed that Ilam Tiraiyan must have subdued Kurumbas, the original inhabitants of the region and established his rule over Tondaimandalam Chennai also known as Madras is the capital city of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Located on the Coromandel Coast off the Bay of Bengal, it is a major commercial, cultural, economic and educational center in South India. It is also known as the "Cultural Capital of South India" The area around Chennai had been part of successive South Indian kingdoms through centuries. The recorded history of the city began in the colonial times, specifically with the arrival of British East India Company and the establishment of Fort St. George in 1644. On Chennai's way to become a major naval port and presidency city by late eighteenth century. Following the independence of India, Chennai became the capital of Tamil Nadu and an important centre of regional politics that tended to bank on the Dravidian identity of the populace. According to the provisional results of 2011 census, the city had 4.68 million residents making it the sixth most populous city in India; the urban agglomeration, which comprises the city and its suburbs, was home to approximately 8.9 million, making it the fourth most populous metropolitan area in the country and 31st largest urban area in the world. -

EVOLUTION of SBI the Origin of the State Bank of India Goes Back to the First Decade of the Nineteenth Century with the Establis

EVOLUTION OF SBI [Print Page] The origin of the State Bank of India goes back to the first decade of the nineteenth century with the establishment of the Bank of Calcutta in Calcutta on 2 June 1806. Three years later the bank received its charter and was re-designed as the Bank of Bengal (2 January 1809). A unique institution, it was the first joint-stock bank of British India sponsored by the Government of Bengal. The Bank of Bombay (15 April 1840) and the Bank of Madras (1 July 1843) followed the Bank of Bengal. These three banks remained at the apex of modern banking in India till their amalgamation as the Imperial Bank of India on 27 January 1921. Primarily Anglo-Indian creations, the three presidency banks came into existence either as a result of the compulsions of imperial finance or by the felt needs of local European commerce and were not imposed from outside in an arbitrary manner to modernise India's economy. Their evolution was, however, shaped by ideas culled from similar developments in Europe and England, and was influenced by changes occurring in the structure of both the local trading environment and those in the relations of the Indian economy to the economy of Europe and the global economic framework. Bank of Bengal H.O. Establishment The establishment of the Bank of Bengal marked the advent of limited liability, joint- stock banking in India. So was the associated innovation in banking, viz. the decision to allow the Bank of Bengal to issue notes, which would be accepted for payment of public revenues within a restricted geographical area. -

Download General Studies Notes PDF for IAS Prelims from This Link

These are few chapters extracted randomly from our General Studies Booklets for Civil Services Preliminary Exam. To read all these Booklets, kindly subscribe our course. We will send all these Booklets at your address by Courier/Post. BestCurrentAffairs.com BestCurrentAffairs.com PAGE NO.1 The Indian money market is classified into: the organised sector (comprising private, public and foreign owned commercial banks and cooperative banks, together known as scheduled banks); and the unorganised sector (comprising individual or family owned indigenous bankers or money lenders and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs)). The unorganised sector and microcredit are still preferred over traditional banks in rural and sub- urban areas, especially for non-productive purposes, like ceremonies and short duration loans. Banking in India, in the modern sense, originated in the last decades of the 18th century. Among the first banks were the Bank of Hindostan, which was established in 1770 and liquidated in 1829-32; and the General Bank of India, established in 1786 but failed in 1791. The largest bank, and the oldest still in existence, is the State Bank of India (S.B.I). It originated as the Bank of Calcutta in June 1806. In 1809, it was renamed as the Bank of Bengal. This was one of the three banks funded by a presidency government; the other two were the Bank of Bombay and the Bank of Madras. The three banks were merged in 1921 to form the Imperial Bank of India, which upon India's independence, became the State Bank of India in 1955. For many years the presidency banks had acted as quasi-central banks, as did their successors, until the Reserve Bank of India was established in 1935, under the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. -

1 an Introduction to Indian Banking System

CHAPTER – 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIAN BANKING SYSTEM INTRODUCTION The banking sector is the lifeline of any modern economy. It is one of the important financial pillars of the financial sector, which plays a vital role in the functioning of an economy. It is very important for economic development of a country that its financing requirements of trade, industry and agriculture are met with higher degree of commitment and responsibility. Thus, the development of a country is integrally linked with the development of banking. In a modern economy, banks are to be considered not as dealers in money but as the leaders of development. They play an important role in the mobilization of deposits and disbursement of credit to various sectors of the economy. The banking system reflects the economic health of the country. The strength of an economy depends on the strength and efficiency of the financial system, which in turn depends on a sound and solvent banking system. A sound banking system efficiently mobilized savings in productive sectors and a solvent banking system ensures that the bank is capable of meeting its obligation to the depositors. In India, banks are playing a crucial role in socio-economic progress of the country after independence. The banking sector is dominant in India as it accounts for more than half the assets of the financial sector. Indian banks have been going through a fascinating phase through rapid changes brought about by financial sector reforms, which are being implemented in a phased manner. The current process of transformation should be viewed as an opportunity to convert Indian banking into a sound, strong and vibrant system capable of playing its role efficiently and effectively on their own without imposing any burden on government. -

Study of Banking Services Provided by Banks in India

www.irjhis.com ©2021 IRJHIS | Volume 2, Issue 6, June 2021 | ISSN 2582-8568 | Impact Factor 5.71 STUDY OF BANKING SERVICES PROVIDED BY BANKS IN INDIA BHADRAPPA HARALAYYA HOD and ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF MBA LINGARAJ APPA ENGINEERING COLLEGE BIDAR- 585403 E-mail: [email protected] Orcid id: 0000-0003-3214-7261 DOI No. 03.2021-11278686 DOI Link :: http://doi-ds.org/doilink/06.2021-78713533/IRJHIS2106002 Abstract: Within the off chance that the monetary base doesn't exist, can you trust you targeted in which you could keep your cash secure? Where do you get an advance from? Who else will you way to deal with accumulate installment in your contributions? Financial institutions are money related foundations that can be crucial for working and essential on a day - to - day reason for monetary boost. You could be astonished to see that banks got been round constantly. There is confirmation of banking profits in memorable situations when vendors across the town borrowed money to ranchers and merchants opposite to their embryon and things. Through the entire long term, financial institutions have formed into monetary establishments which could give and go through cash. With the improvement of period, at present banks aren't just money the business owners administrations. Presently, the administrations offered financial institutions assisted him with reasons to live with the abundant good financial circumstances. This blog can give a clarification to the significance of the financial construction and the various types of bank administrations provided by forefront banks. Keywords: Payment, Online Banking, Mobile Banking and Money Transfer. -

Retirement Planning Products Offered by the State Bank of India and Its Affiliates

© 2021 JETIR January 2021, Volume 8, Issue 1 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Retirement Planning Products Offered by the State Bank of India and Its Affiliates Sharvee Shrotriya, Research Scholar, Department of Commerce and Management, Banasthali Vidyapith, Niwai- 304022, India. ABSTRACT An integral aspect of financial planning is retirement planning. The need for retirement planning is intensified by a rise in overall life expectancy. In addition to providing an extra source of revenue, retirement planning also allows one to cope with medical emergencies, meet life goals, and remain financially independent. The State Bank of India and other commercial banks and financial institutions have brought out many products and schemes to facilitate retirement planning procedures. However, the plans are not organized enough to be accessible to the public. The degree of effectiveness of these plans and their execution are some of the things that raise concern. The retirement planning among women and the ways of delivering services by the bank is yet to be researched. The study is based on secondary data. The research shows that apart from measures taken by the SBI for the betterment of retirement planning, the products launched are not ample. It is essential to ensure that retirement planning is started by youngsters at an early age and the banks lubricate the process with their innovative, accessible, and customer-friendly products. Key Words- Financial Planning, SBI and Retirement Planning. 1. INTRODUCTION Famously known as the SBI, the State Bank of India, with its headquarters in Mumbai, Maharashtra, is the largest commercial bank of India. It is not some public sector banking and financial services company but it is also classified as an Indian Multinational. -

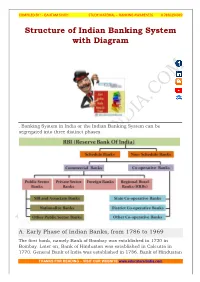

Structure of Indian Banking System with Diagram

COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – BANKING AWARENESS 0 7830294949 Structure of Indian Banking System with Diagram . Banking System in India or the Indian Banking System can be segregated into three distinct phases: A. Early Phase of Indian Banks, from 1786 to 1969 The first bank, namely Bank of Bombay was established in 1720 in Bombay. Later on, Bank of Hindustan was established in Calcutta in 1770. General Bank of India was established in 1786. Bank of Hindustan THANKS FOR READING – VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.educatererindia.com COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – BANKING AWARENESS 0 7830294949 carried on the business till 1906. First Joint Stock Bank with limited liability established in India in 1881 was Oudh Commercial Bank Ltd. East India Company established the three independently functioning banks, also known by the name of “Three Presidency Banks” - The Bank of Bengal in 1806, The Bank of Bombay in 1840, and Bank of Madras in 1843. These three banks were amalgamated in 1921 and given a new name as Imperial Bank of India. After Independence, in 1955, the Imperial Bank of India was given the name "State Bank of India". It was established under State Bank of India Act, 1955. In the surcharged atmosphere of Swadeshi Movement, a number of private banks with Indian managements had been established by the businessmen from mid of the 19th century onwards, prominent among them being Punjab National Bank Ltd., Bank of India Ltd., Canara Bank Ltd, and Indian Bank Ltd. The first bank with fully Indian management was Punjab National Bank Ltd. established on 19 May 1894, in Lahore (now in Pakistan).