Bohemian Faceted-Spheroidal Mold-Pressed Glass Bead Attributes: Hypothesized Terminus Post Quem Dates for the 19Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana's Glass Beadmaking Arts in Transcultural Dialogues

Ghana’s Glass Beadmaking Arts in Transcultural Dialogues Suzanne Gott PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR EXCEPT WHERE OTHERWISE NOTED hanaian powder-glass beads first captured spread of West African strip-weaving technologies. my attention in 1990, when closely examin- With the beginnings of European maritime trade in the late ing a strand of Asante waist beads purchased fifteenth century, an increasing volume of glass beads and glass in Kumasi’s Central Market. Looking at the goods were shipped to trade centers along present-day Ghana’s complex designs of different colored glasses, Gold Coast,1 stimulating the growth of local beadworking and I was struck with the realization that each powder-glass beadmaking industries. The flourishing coastal bead had been skillfully and painstakingly crafted. This seem- trade achieved a more direct engagement between European Gingly humble and largely unexamined art merited closer study merchants and trading communities than had been possible and greater understanding (Fig. 1). I worked with Christa Clarke, with the trans-Saharan trade, and enhanced European abilities Senior Curator for the Arts of Global Africa at the Newark to ascertain and respond to local West African consumer pref- Museum, to develop the 2008–2010 exhibition “Glass Beads of erences. This interactive trade environment also facilitated the Ghana” at the Newark Museum to introduce the general public impact of the demands of Gold Coast consumers on European to this largely overlooked art (Fig. 2). The following study pro- product design and production, a two-way dynamic similar to vides a more in-depth examination of Ghanaian glass beadmak- the trade in African-print textiles (Nielsen 1979; Steiner 1985). -

Fiscal Year 2007 Annual Report (PDF)

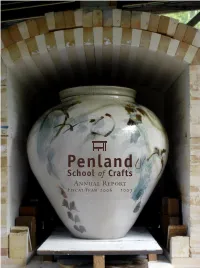

Penland School of Crafts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2006 – 2007 Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland’s programs engage the human spirit which is expressed throughout the world in craft. Penland enriches lives by teaching skills, ideas, and the value of the handmade. Penland welcomes everyone—from vocational and avocational craft practitioners to interested visitors. Penland is a stimulating, transformative, egalitarian place where people love to work, feel free to experiment, and often exceed their own expectations. Penland’s beautiful location and historic campus inform every aspect of its work. Penland’s Educational Philosophy Penland’s educational philosophy is based on these core ideas: • Total immersion workshop education is a uniquely effective way of learning. • Close interaction with others promotes the exchange of information and ideas between individuals and disciplines. • Generosity enhances education—Penland encourages instructors, students, and staff to freely share their knowledge and experience. • Craft is kept vital by preserving its traditions and constantly expanding its boundaries. Cover Information Front cover: this pot was built by David Steumpfle during his summer workshop. It was glazed and fired by Cynthia Bringle in and sold in the Penland benefit auction for a record price. It is shown in Cynthia’s kiln at her studio at Penland. Inside front cover: chalkboard in the Pines dining room, drawing by instructor Arthur González. Inside back cover: throwing a pot in the clay studio during a workshop taught by Jason Walker. Title page: Instructors Meg Peterson and Mark Angus playing accordion duets during an outdoor Empty Bowls dinner. -

The Bead Forum 73

Issue 73 Autumn 2018 A Glass-Beadmaking Furnace at Schwarzenberg in the Bohemian Forest, Upper Austria Kinga Tarcsay and Wolfgang Klimesch Translated by Karlis Karklins he village of Schwarzenberg is located in located outside the village, directly in sight of the the so-called Mühlviertel, an area of Up- borders of Bavaria and Bohemia. Over the years, Tper Austria which geologically belongs glass beads have been found repeatedly on the to the Bohemian massif and is thus part of that property south of the estate at Schwarzenberg 93, large cross-border glassworks landscape that in- which led to a one-week archaeological excavation cluded the Bohemian Forest, the Bavarian Forest, carried out in 2017 on the initiative of local histo- the Mühlviertel, and the Waldviertel since the rian Franz Haudum. 14th century. The glassworks site discussed here is Two test units were opened. Unit 1 revealed part of a glass oven which was attached to a massive, roughly cir- cular, boulder over 3 m in diameter (Figure 1). The oven had a round- ed end and the exposed portion was 3.8 m long. The masonry, of which only the lowest layer remained, consist- ed of irregular granite stones laid without mortar. The exterior wall was clearly defined and 0.7 m thick. As for the interior, at the pres- ent state of exposure, no clear distinction could be made between collapsed material and a possible building struc- ture. Nevertheless, a transverse wall running Figure 1. Aerial view of the glass furnace in excavation Unit 1 (7 x 6.5 m) (photo: Sieg- approximately north- fried Hoheneder, Schwarzenberg). -

The Coming Museum of Glass Newglass Review 23

The Coming Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 23 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 2002 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made between der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, dass sie zwi- October 1, 2000, and October 1, 2001. schen dem 1. Oktober 2000 und dem 1. Okto- ber 2001 entworfen und gefertig wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare der New Glass please contact: Rew'ewkonnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Buying Office One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 Telephone: (607) 974-6821 Fax: (607) 974-7365 E-mail: [email protected] To Our Readers An unsere Leser Since 1985, New Glass Review has been printed by Seit 1985 wird New Glass Review von der Ritterbach Ritterbach Verlag GmbH in Frechen, Germany. This Verlag GmbH in Frechen, Deutschland, gedruckt. Dieser firm also publishes NEUES GLAS/NEW GLASS, a Verlag veroffentlicht seit 1980 auBerdem NEUES GLAS/ quarterly magazine devoted to contemporary glass- NEW GLASS, eine zweisprachige (deutsch/englisch), making. vierteljahrlich erscheinende Zeitschrift, die iiber zeitge- New Glass Review is published annually as part of the nossische Glaskunst weltweit berichtet. April/June issue of NEUES GLAS/NEW GLASS. It is Die New Glass Review wird jedes Jahr als Teil der Mai- also available as an offprint. Both of these publications, ausgabe von NEUES GLAS/NEW GLASS veroffentlicht. as well as subscriptions to New Glass Review, are avail Sie ist aber auch als Sonderdruck erhaltlich. -

Zhou Dynasty Glass and Silicate Jewelry Zhou

Zhou Dynasty Glass anD silicate Jewelry Robert K. Liu ince I began studying the faience, glass and other piece-mold and core-casting, while the latter employed silicate ornaments of the Zhou Dynasty in 1975, this similarly advanced lapidary technology. Even in the 1970s, S field has undergone a sharp dichotomy. While I realized that these early Chinese glassworkers had adapted previously mostly foreign scientists or Chinese outside of some of these same techniques for fabricating their glass China researched their chemical makeup, age and stylistics, ornaments, as seen in mold-cast, press-molded and lapidary- in the past decades Chinese themselves have begun to finished Zhou and Han glass artifacts. My own research on intensively study their composition, through sophisticated composite beads also implicates the role of early ceramics. non-destructive techniques like XRF and Raman While much information is now available to those spectroscopy, but with little attention to their typology, interested in the fascinating array of silicate ornaments chronology or how they were made or used, despite the from the Zhou Dynasty, it is difficult to apply this data enormous increase in number of excavated sites bearing easily towards their dating/chronology and typology, nor such beads (Gan 2009; Kwan 2001, 2013; Lankton and to realize how deeply glass and other silicate usage Dussubieux 2006, 2013; Li et al., 2015; Liu 1975, 1991, penetrated into Chinese society during these very turbulent 2005, 2013; Yang et al., 2013; Zhu 2013). Now regarded as times of constant warfare and intellectual foment of the important cultural relics, beads of the Zhou/Han times were Zhou/Warring States period, as evident by artifacts shown widely sold since at least the 1990s on the world antiquities on page 57, although glass sword furniture of the Mid-to-Late markets, often sourced by looting, and which are still W.S. -

The Glass Beads Game

ITALY GHANA - CAMEROON THE GLASS BEADS GAME ©Bruno Zanzottera The Fondamenta dei Vetrai canal in Murano THE ‘GLASS BEADS GAME’ TELLS THE STORY OF THE VENETIANS GLASS BEADS AND THEIR TRADE TO AFRICA, WHERE THEY ARE STILL USED BY MANY TRIBES WITH DIFFERENT PURPOSES. THE ART OF GLASS BEADMAKING COULD NOW BE ADDED TO THE UNESCO LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE. In 1352 the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta, left his native Tangiers and set out to the Kingdom of Mali. In his descriptions of the country and people’s customs, Battuta wrote: “in this country travelers do not carry provisions with them,and not even ducats or drachmas. They bring salt pieces, glass ornaments or custom jewelry that people call nazhms (strings of glass beads) and some spices”. Venetian glass beads production is rooted in very ancient traditions and harks back to the Roman and Byzantine handcraft. Recently UNESCO approved the dossier compiled by Italy and France for this art to be recognised as part of Humanity’s Intangible Heritage. Thanks to the Golden Bull granted to Venetian merchants by the basileus of Constantinople in 1082, Venice expanded the trade with the Southern Mediterranean basin. In the XV century, after the fall of Constantinople conquered by Ottoman Turks in 1453, and above all thanks to the discovery of the New World, trade routes changed dramatically. The Gulf of Guinea became the new commercial pole where Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and English ships unloaded their goods for trading. Among these goods, Venetian glass beads were used as coins, with their “magic” beauty, handiness and resistance. -

Hot Glass -- Section B

Call Toll-Free Section B 1-800-828-7159 HOT GLASS KILNS FUSING AND HOT GLASS H Kilns And Supplies You Will Need O Glass fusing continues to be the hottest interest for stained glass enthusiasts. From creating unique jewelry, to slumping bowls or vases, fusing is a fun and exciting aspect to glass working. T This section has kilns by Evenheat, Fireworks beadmaking equipment, Reusche and Fusemaster glass paints and brushes, COE 90 Tested Compatible glass, CBS Dichroic glass, System 96 materials, slumping and draping molds by Creative Paradise and Colour De Verre and MORE! Check throughout the catalog for related supplies such as jewelry findings, band saws and ring saws, and other items that make hot glass easier and more exciting. G EVENHEAT KILNS Evenheat Kilns have a worldwide reputation for solid construction, reliability and long life. All are L made in the USA, and come with instructions and service manuals. Kiln shelves are NOT included. A The line runs from their Rapid Fire table top kiln for small projects to their top loaders and the heavy duty digitally controlled front loading kilns. Table Top Kilns S Evenheat has produced four compact, easy to use kilns. All operate on standard 120 volt circuits, so no special wiring is S required. STUDIO 8 KILN – Like its tough little brother the Hot Box, the Studio 8 is quite STUDIO PRO KILN – has the same size and heating features as the Studio 8 above capable of all glass related firings up to 1800°F. It also has the speed and power but with an easier Dual Access Design. -

Leah Fairbanks Leah Fairbanks Is a Well Known Contemporary Glass Artist Recognized for Her Distinct Floral Handmade Glass Beads

Leah Fairbanks Leah Fairbanks is a well known contemporary glass artist recognized for her distinct floral handmade glass beads. She attended the Academy Of Art in San Francisco where she explored many medium with her main focus on printmaking and fashion Design. Leah began her glass career in 1983 specializing in large commission pieces. She explored and pushed the limits of the medium creating stained glass windows, neon sculptures, fused glass plates, bowls and jewelry. Leah’s first lampworked class in 1992 guided the course of her path into the realm of hot glass. Leah was intimately involved in the resurgence of professional flameworked glass beadmaking in America during the 1990’s. Leah’s exploration in garden motifs directly influenced and impacted the early movement of floral decoration in contemporary beadmaking. Leah provided direction in this art form in it’s formative stage in her role as Secretary/Treasurer from 1994 to 1995. Articles about her works have been in numerous books and publications: LAMMAGA Magazine, Ornament Magazine, Bead And Button Magazine, Lapidary Journal, Masters: Glass Beads By Lark Books, Making Glass Beads & Beads Of Glass by Cindy Jenkins, 1000 Glass beads: Innovation & Imagination In Contemporary Glass Beadmaking, Lark Books, Contemporary Lampworking: A Practical Guide to Shaping Glass in the Flame and Formed of Fire, by Bandhu S. Dunham. As an accomplished instructor, Leah has taught beginning to advanced glass beadmaking workshops nationwide since 1994. She has taught classes throughout the United States and abroad which include Canada, Japan, Ireland, France, Australia, Denmark, Holland and Italy. Leah has the honor of being exhibited in The Corning Museum Of Glass Permanent Collection, Corning N.Y., The Contemporary Glass Collection: The Bead Museum Permanent Collection, Washington D.C., The KOBE Lampwork Museum and many more private collections throughout the world. -

Pdf Download

nA1Pfn fifeF~!I'\T I .' un t' Ii; I·'lt;~~ The journal of the Center for Bead Research Volume 13, Number! Issue 29 2000 ' ~~ ~ARGARETOlO~ ~ The Beads of Bohemia Timeline - Bohemian Beads: Outside Influences, Technology Export and Bead Types Outside Bohemia Within Bohemia Bohemian beads 1359 glasshouse in Vim perk, S. Bohemia 1376 Sklanai'ice (glassmaking village) 1490 Venice making drawn beads 1548 glasshouse at Mseno (Jablonec) 1650 "Roman pearls" in Paris by 1680 red composition by 1680 molded, 1737 glass cutters in Jablonec faceted garnet 1750 lampworking in imitations . Venice 1764174 "mandrel" tong molds 1789 Klaproth 1782 First Czech seed beads discovers uranium 1800 Atlas (satin) 1810 blown glass glass with cut beads in 'Lauscha corners 1815·1866 Bohemia 1820 Anna (uranium) yellow and green 1820 "Vaseline" and Venice united beads;" hexagonal under Austria ~. blues with cut 1840 Prosser corners machine 1841 Altmuller records lampworking 1841 Venetian 1845 blown glass beads in Bohemia rocailles faceted as 1850 silver-lining at charlottes Lauscha ' 18505·1900 beads imitating materials, 1856 irising invented 18561ustering invented objects, exotic in Hungary late 1800s Sample Men gather exotic beads, Venetian 1864 Bapterosses beads to send home for copying beads; beads for makes "Prosser" 1866 outselling Venice the Muslim market beads in France 1876 Multiple mold for blown beads and others 1883 Riedl patents internal grooving for blown beads 1884 tong molds with straight holes 1887 Reidl improves drawing, tumbling of 1897 Well-made seed seed beads; rocia/les beads 1890 Redlhammers making "Prosser 1895 Swarovski to beads" Austria early 1900s snake, 1900? Blown beads interlocking beads made in Japan 1900 Art Nouveau 1941 lampwinding and art beads taught in India: 19205 "Tut" beads 1945 Germans 1945 Beadmaking goes into decline expelled 1970? India making blown beads 1992 Velvet revolution; revival The MARGARETOLOOIST is published twice a year with the most current information on bead research, primarily our own. -

10Th Annual Gallery of Women in Glass 6 Featuring the Work of 123 Female Flameworking Artists

Winter 2014 10th Annual A glass journal for the flameworking community Gallery of Women in Glass Kathryn Guler Tutorials by Penny Dickinson Gina Gaffner $9.00 U.S. $10.00 Canada Vol 12 Number 4 Maureen Henriques Deborah Read Lisa St. Martin Elise Strauss Publisher ~ Maureen James Editor ~ Jennifer Menzies Dear Readers, Founding Editor ~ Wil Menzies We are thrilled to bring you the latest Women in Glass Copy Editor ~ Darlene Welch issue of The Flow. This 10th annual showcase of the work Accounting ~ Rhonda Sewell of over 120 female flameworking artists reminds us just how Circulation Manager ~ Kathy Gentry imaginative we ladies can be when it comes to expressing ourselves in glass. You’ll also find six terrific tutorials for Advertising ~ Maureen James soft and boro projects that include dichroic coated copper Graphic Artists ~ Dave Burnett foil and silver glass encased floral beads, tips for creating Mark Waterbury simple faces, and painted focal beads. Add the Glasscaster Contributing Artists and Writers interview with flameworking maven, Liz Mears, plus the Christine Ahern, Marcie Davis profile on the latest adventures of artist Laurie Young, and Penny Dickinson, Gina Gaffner we think you’ll agree that this one great issue. Maureen Henriques, Jennifer Menzies All of us at The Flow want to thank you, our readers, for your continued support Deborah Read, Lisa St. Martin over the past year. We count it a privilege to bring you this enduring resource to Elise Strauss, Laurie Young help make your glass art better than ever. In a world where many people think that Darlene Welch digital media has surpassed the printed word, it’s interesting to note that magazine ISSN 74470-28780 is published quarterly readership in general has actually risen over the past five years. -

Additional Resources—General Studio Safety

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES—GENERAL STUDIO SAFETY Books and Journals American Scientific Glassblowers Society. Methods and materials. [Toledo, OH]: American Scientific Glassblowers Society, [1995]. 1 v. Note: Materials, methods, safety hazards. Bray, Charles. Ceramics and glass: a basic technology. Sheffield, England: Society of Glass Technology, 2000. 276 p. Note: "Written for students, potters and glassmakers working individually or in small studios." Excellent source for basic chemistry of glass; also information about raw materials, kilns, refractory and insulating materials, adhesives, color, etc. Chapter on safety, pp. 233-237. Bray, Charles. Dictionary of glass: materials and techniques. 2nd ed. London: A & C Black; Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. 256 p., [16] p. of plates. Background information on materials, process, and techniques. Includes a section on safety, pp. 204-206, plus entries for silicosis, pneumoconiosis, acids, as well as many other safety related topics. Cheremisinoff, Paul N. A guide to safe material and chemical handling. Cheremisinoff, Paul N.; Hoboken, N.J : Wiley, 2010. 480 pp. Clark, Nancy. Ventilation. By Nancy Clark, Thomas Cutter, and Jean-Ann McGrane. New York: Lyons & Burford, [n.d., 1986?] viii, 117 p. Note: Originally published: New York: Center for Occupational Hazards, 1984. Dunham, Bandhu Scott. Contemporary Lampworking: A Practical Guide to Shaping Glass in the Flame. 3rd ed. Prescott, AZ: Salusa Glassworks, 2002. Includes artistic and technical information and a good resource list. "Setting up a lampwork studio," pp. 57-80; "Teaching studio recommendations," pp. 465-468; "Health and safety for lampworkers," p. 229-244; "Chemical hazards," p. 481-486. http://www.salusaglassworks.com/book.html Dunham, Bandhu Scott. -

Imitation Pearls in France

BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers Volume 8 Volume 8-9 (1996-1997) Article 6 1996 Imitation Pearls in France Marie-José Opper Howard Opper Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Opper, Marie-José and Opper, Howard (1996). "Imitation Pearls in France." BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 8: 23-34. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads/vol8/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMITATION PEARLS IN FRANCE Marie-Jose Opper and Howard Opper To achieve the perfect imitation pearl has been the goal ofnu Before Jacquin's important discovery in 1686, merous European beadmakers for over 700 years. In France, mercury was used to give hollow clear-glass beads a the art of making false-pearls spread rapidly after Jacquin pearl-like luster. As a merchant dealing in these beads, discovered how to fill hollow glass beads with a pearl-like Jacquin was well aware of the toxicity of the substance substance in the 17th century. Since that time, many. diverse It recipes have been tried and used to satisfy the French pub and the health hazards for both makers and wearers. was lic's enormous appetite for affordable, yet elegant, imita his daughter-in-law's request for a necklace of false tions offine pearls.