What Are the Safety Issues Associated with Glass Beadmaking?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FUSED GLASS PLAID PLATE Free Fused Glass Project

Come Join Us! FUSED GLASS PLAID PLATE Free Fused Glass Project #551 Materials List: Materials List for COE 90 or COE 96 COE 90 Item# 90905 (Qty 2) White Opal Base Sheet Glass 8 x 8 OR use Clear Glass and make sure of slumping mold size) Item# 90915 Qty 1 Clear Sheet Glass 8 x 8 Item# 90906 Qty 1 Deep Royal Purple Sheet Glass 8 x 8 Item# 90945 Qty 1 Green Sheet Glass 8 x 8 Item# 90902 Qty 1 Light Turquoise Sheet Glass 8 x 8 COE 96 Item# 96905 (Qty 2) White Opal Base Sheet Glass 8 x 8 OR use Clear Glass and make sure of slumping mold size) Item# 96915 Qty 1 Clear Sheet Glass 8 x 8 Item# 96906 Qty 1 Deep Royal Purple Sheet Glass 8 x 8 Item# 96945 Qty 1 Green Sheet Glass 8 x 8 Item# 96902 Qty 1 Light Turquoise Sheet Glass 8 x 8 FUSING SUPPLIES: Other Items: Item# 41513 Bullseye Shelf Paper 1 square foot or Item# 41514 Papyros Shelf Paper 1 square foot Item# 41232 Mold Curved Square (This project will work other square molds and look wonderful so do not limit yourself to just one mold.) Item# 41507 Fuser's Glue Other Materials: · Cold Polishing - (one of the following) · Grinder · Abrasive Stone · Diamond Nail File · 3M™ Diamond Coated Sanding Sponges Clean Up Supplies: · Rubbing Alcohol, Dish Washing Detergent · Cloth with very little lint (old T-shirt) Step 1 - Preparation · Grind to round each of the 4 corners of the larger square used as the base piece of glass. -

Ghana's Glass Beadmaking Arts in Transcultural Dialogues

Ghana’s Glass Beadmaking Arts in Transcultural Dialogues Suzanne Gott PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR EXCEPT WHERE OTHERWISE NOTED hanaian powder-glass beads first captured spread of West African strip-weaving technologies. my attention in 1990, when closely examin- With the beginnings of European maritime trade in the late ing a strand of Asante waist beads purchased fifteenth century, an increasing volume of glass beads and glass in Kumasi’s Central Market. Looking at the goods were shipped to trade centers along present-day Ghana’s complex designs of different colored glasses, Gold Coast,1 stimulating the growth of local beadworking and I was struck with the realization that each powder-glass beadmaking industries. The flourishing coastal bead had been skillfully and painstakingly crafted. This seem- trade achieved a more direct engagement between European Gingly humble and largely unexamined art merited closer study merchants and trading communities than had been possible and greater understanding (Fig. 1). I worked with Christa Clarke, with the trans-Saharan trade, and enhanced European abilities Senior Curator for the Arts of Global Africa at the Newark to ascertain and respond to local West African consumer pref- Museum, to develop the 2008–2010 exhibition “Glass Beads of erences. This interactive trade environment also facilitated the Ghana” at the Newark Museum to introduce the general public impact of the demands of Gold Coast consumers on European to this largely overlooked art (Fig. 2). The following study pro- product design and production, a two-way dynamic similar to vides a more in-depth examination of Ghanaian glass beadmak- the trade in African-print textiles (Nielsen 1979; Steiner 1985). -

Bullseye Glass Catalog

CATALOG BULLSEYE GLASS For Art and Architecture IMPOSSIBLE THINGS The best distinction between art and craft • A quilt of color onto which children have that I’ve ever heard came from artist John “stitched” their stories of plants and Torreano at a panel discussion I attended a animals (page 5) few years ago: • A 500-year-old street in Spain that “Craft is what we know; art is what we don’t suddenly disappears and then reappears know. Craft is knowledge; art is mystery.” in a gallery in Portland, Oregon (page 10) (Or something like that—John was talking • The infinite stories of seamstresses faster than I could write). preserved in cast-glass ghosts (page 25) The craft of glass involves a lifetime of • A tapestry of crystalline glass particles learning, but the stories that arise from that floating in space, as ethereal as the craft are what propel us into the unknown. shadows it casts (page 28) At Bullseye, the unknown and oftentimes • A magic carpet of millions of particles of alchemical aspects of glass continually push crushed glass with the artists footprints us into new territory: to powders, to strikers, fired into eternity (page 31) to reactive glasses, to developing methods • A gravity-defying vortex of glass finding like the vitrigraph and flow techniques. its way across the Pacific Ocean to Similarly, we're drawn to artists who captivate Emerge jurors (and land on the tell their stories in glass based on their cover of this catalog) exceptional skills, but even more on their We hope this catalog does more than point boundless imaginations. -

English Cameo Glass

ENGLISH CAMEO GLASS THE CORNING MUSEUM OF GLASS ENGLISH CAMEO GLASS IN THE CORNING MUSEUM OF GLASS DAVID WHITEHOUSE THE CORNING MUSEUM OF GLASS CORNING, NEW YORK Cover: Moorish Bathers. England, Amblecote, Thomas Webb & Sons, carved and engraved by George Woodall, 1898. D. 46.3 cm. The Corning Museum of Glass (92.2.10, bequest of Mrs. Leonard S. Rakow). Copyright © 1994 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Editor: John H. Martin Photography: Nicholas L. Williams Design and Typography: Graphic Solutions, Corning, New York Printing: Upstate Litho, Rochester, New York Standard Book Number 0-87290-134-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 94-071702 FRONTISPIECE. The Great Dish. CONTENTS Preface 7 Introduction 11 The Early Years 17 Stevens & Williams 31 Thomas Webb & Sons 33 A Woodall Miscellany 42 Epilogue 56 Further Reading 58 Notes on the Illustrations 59 Notes 63 FIG. 1. The Portland Vase. PREFACE THIS SHORT BOOK has two objectives: to cele- makers tried unsuccessfully to make a replica of brate the achievements of 19th-century English it, and in the 1820s and 1830s several silver ver- cameo glass makers and to focus attention on the sions were made by the London firm of Rundle, outstanding examples of their work in the collec- Bridge, and Rundell. tion of The Corning Museum of Glass. In the early 19th century—possibly as early Cameos are objects with two or more layers as 1804—glassmakers in Bohemia began to of different colors. The outer layer or layers are "case," or cover, colorless glass with a layer of partly removed to create relief decoration on a colored glass that was then cut through to reveal background of contrasting color. -

Baltic Glass the Development of New Creative Models Based on Historical and Contemporary Contextualization

Vesele, Anna (2010) Baltic Glass The development of new creative models based on historical and contemporary contextualization. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/3659/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Baltic Glass The development of new creative models based on historical and contemporary contextualization Anna Vesele A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Sunderland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, University of Sunderland April 2010 1 Abstract The aim of this research was to demonstrate the creative potential of a particular type of coloured flat glass. This glass is produced in Russia and is known as Russian glass. The present researcher has refined methods used by Baltic glass artists to create three- dimensional artworks. The examination of the development of glass techniques in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania was necessary in order to identify these methods and to contextualize the researcher’s personal practice. This study describes for the first time the development of glass art techniques in the Baltic States from the 1950s to the present day. A multi-method approach was used to address research issues from the perspective of the glass practitioner. The methods consisted of the development of sketches, models and glass artworks using existing and unique assembling methods. The artworks underlined the creative potential of flat material and gave rise to a reduction in costs. In conjunction with these methods, the case studies focused on the identification of similarities among Baltic glass practices and similarities of approach to using various glass techniques. -

Bohemian Faceted-Spheroidal Mold-Pressed Glass Bead Attributes: Hypothesized Terminus Post Quem Dates for the 19Th Century

BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers Volume 15 Volume 15 (2003) Article 6 1-1-2003 Bohemian Faceted-Spheroidal Mold-Pressed Glass Bead Attributes: Hypothesized Terminus Post Quem Dates for the 19th Century Lester A. Ross Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Ross, Lester A. (2003). "Bohemian Faceted-Spheroidal Mold-Pressed Glass Bead Attributes: Hypothesized Terminus Post Quem Dates for the 19th Century." BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 15: 41-52. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads/vol15/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOHEMIAN FACETED-SPHEROIDAL MOLD-PRESSED GLASS BEAD ATTRIBUTES: HYPOTHESIZED TERMINUS POST QUEM DATES FOR THE 19TH CENTURY Lester A. Ross Faceted-spheroidal mold-pressed beads have been manufactured Glass bead varieties and their attributes occasionally in Bohemia since the 18th century. Evolution of manufacturing have proven to be reliable as sensitive temporal markers technology has resulted in the creation of bead attributes that (e.g., Karklins 1993; Sprague 1983, 1985). Well-dated can readily be observed on beads from archaeological contexts. archaeological contexts containing faceted-spheroidal mold Many North American archaeological sites contain examples of pressed beads appear to be restricted to the second through this bead type; but few reports have identified the attributes, much fourth quarters of the 19th century. -

Download New Glass Review 11

The Corning Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 11 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1990 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within derVoraussetzung ausgewahlt, da(3 sie the 1989 calendar year. innerhalb des Kalenderjahres 1989 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare des New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Sales Department One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 (607) 937-5371 All rights reserved, 1990 Alle Rechte vorbehalten, 1990 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Dusseldorf FRG Gedruckt in Dusseldorf, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-87290-122-X ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der KongreB-Bucherei 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81-641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstler und Objekte 9 Bibliography/Bibliographie 30 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Verzeichnis der Eigennamen und Orte 53 Is das Jury-Mitglied, das seit dem Beginn der New Glass Review Jury Statements A1976 kein Jahr verpaBt hat, fuhle ich mich immer dazu verpflichtet, neueTrends und Richtungen zu suchen und daruber zu berichten, wel- chen Weg Glas meiner Meinung nach einschlagt. Es scheint mir zum Beispiele, daB es immer mehr Frauen in der Review gibt und daB ihre Arbeiten zu den Besten gehoren. -

Lazy Man's Guide to Stained Glass

A Lazy Man’s Guide to Stained Glass Professional tips, tricks, and shortcuts 3rd Edition by Dennis Brady Published by: DeBrady Glass Studios 566 David St. Victoria, B.C. V8T 2C8 Canada Tele: (250) 382-9554 Email: [email protected] Website: www.glasscampus.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage system, without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a critical article or review. Copyright 2002 by Dennis Brady Printed in Canada This book is dedicated to my son Brant. He introduced me to stained glass and helped me start DeBrady Glass Studios. It’s unfortunate he couldn’t stay long enough to see what it became. Recognition Covers and Illustrations by: Lar de Souza 4 Division Street Acton, Ontario L7J 1C3 CANADA Tele: (519) 853-5819 Fax: (519) 853-1624 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.lartist.com/ Swag lamp and transom: Inspired by designs from Somers-Tiffany Inc 920 West Jericho Turnpike Smithtown, NY 11787 Tele: (631) 543-6660 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.somerstiffany.com Prairie table lamp: Inspired by a design by Dale Grundon 305 Lancaster Ave Mt. Gretna, PA 17064 Tele: (717) 964-2086 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.DaleGrundon.com Acknowledgement So many people helped me over the years that there wouldn’t be space here to say thank you to all those it was due. -

Glass Shards • Page 2

GlassNEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL Shards AMERICAN GLASS CLUB www.glassclub.org Founded 1933 A Non-Profit Organization Autumn 2019 New Bedford Museum of Glass on the Move! After 3 months of heroic effort last Mt. Washington Glass Company, will relocation possible: Aaron Barr, Mary spring by a team of dedicated volun provide a perfect home for the muse Jo Baryza, Jeff Costa, David DeMello, teers, the New Bedford Museum of um, and we expect to open our new Brian Gunnison, Peggy Hooper, Maria Glass is happy to report that it has fully glass galleries there later this year. Martell, Luis Marquez, Charlie Moss, vacated its former premises and is now Heart-felt thanks to the following Andrea Natsios, Betsy Nelson, Eric making steady progress toward set volunteers (many NAGC members Nelson, Ross Nelson, Karen Petraglia, ting up its new gallery, library, office, among them!) who helped make our and Clint Sowle. and shop spaces in downtown New Bedford’s magnificent James Arnold Mansion! Literally thousands of ex amples of beautiful glass, including art glass, paperweights, early Ameri can glass, and studio glass by contem porary artists, have been carefully packed and moved to the new location, along with more than 50 massive dis play cases, a library of 15,000 glass reference books, and countless fasci nating odds and ends that help tell the story of approximately 2,500 years of glassmaking history. The mansion, which served as the residence in the 1870s and ’80s of William J. Rotch, the president of New Bedford’s famous The new home of the New Bedford Glass Museum. -

New York City Department of Design + Construction

NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF DESIGN + CONSTRUCTION November 2012 HISTORIC STRUCTURE REPORT: Park Slope Library Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor David J. Burney, FAIA, Commissioner David Resnick, AIA, Deputy Commissioner Prepared by the DDC Historic Preservation Office, Architecture + Engineering Unit, Public Buildings Division, Department of Design and Construction. INTRODUCTION 4 HISTORY 6 ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION—ExTERIOR 8 Siting and Massing . .8 Masonry . .10 Windows . 12 Doors . 12 Roof . .13 Site Features . 13 EXTERIOR CHANGES 14 Masonry . 16 Windows . 17 Doors . 17 Roof . .18 Site Features . 19 ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION—INTERIOR 21 Original and Current Layout . 21 Main Public Rooms on First, Mezzanine, and Second Floors: Vestibule, Adults’ and Children’s Reading Rooms, Delivery (Circulation) Area, Book Stacks, Upper and Lower Reference Alcoves, North and South Study Rooms . .27 Ornamental Glass . 30 Woodwork . 31 Plaster Finishes . 35 Fireplaces . 36 Floors . 37. Lighting . 37. Individual Room Descriptions and Significant eatures:F First, Mezzanine, and Second Floors . 41 Delivery Room (now Circulation Area) . 41. Vestibule . 41 Book Stacks . 43 PARK SLOPE LIBRARY / GENERAL INFORMATION 1 Staff Room (now Program Room), First Floor South off the Book Stacks . 44 Librarians’ Office (now elevator lobby, accessible restrooms, and rear entrance vestibule) . 44 First Floor Reference Alcove (now Work Room) . 45 Mezzanine Floor Reference Alcove (now Quiet Reading Room) . 45 Second Floor South Study Room (now a staff workroom or storage room) . 48 Second floor North Study Room . 49 Individual Room Descriptions and Significant Features: Basement Floor49 Main Lecture Hall . 49 Reception Room . 50 Small Lecture Room . 51 Lower Vestibule . .51 Other Basement Spaces . 52 MECHANICAL SysTEM 53 STRUCTURAL SysTEM 55 TECHNOLogy 56 THE 1949 RENOVation 58 THE 1979 RENOVation 59 Windows . -

Fusing Fusing

® Artist Robert Wiener FusingFusing ToolsTools && AccessoriesAccessories ProductProduct CatalogCatalog www.dlartglass.com © 2019 D&L Art Glass Supply © 2019 D&L Art Glass Artist Nancy Bonig 303.449.8737 • 800.525.0940 Table of Contents About the Artwork Cover - Artist: Robert Wiener, DC Art Glass Series: Colorbar Murrine Series Title: Summer Salsa Size: 6" square (approx.) Website: www.dcartglass.com Photographer: Pete Duvall Table of Contents- Alice Benvie Gebhart Title: Distant Fog Size: 6 x 8" Website: www.alicegebhart.com Kilns ..........................................................................1-16 Tabletop Kilns .......................................................................................................... 1–3 120 Volt Kilns ............................................................................................................1-5 240 Volt Kilns ........................................................................................................ 6-12 Kiln Controllers at a Glance .....................................................................................13 Kiln Shelves .......................................................................................................... 14–15 Kiln Furniture and Accessories ................................................................................16 Kiln Working Supplies ....................................... 17-20 Primers & Shelf Paper ...............................................................................................17 Fiber Products & Release -

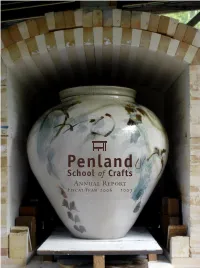

Fiscal Year 2007 Annual Report (PDF)

Penland School of Crafts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2006 – 2007 Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland’s programs engage the human spirit which is expressed throughout the world in craft. Penland enriches lives by teaching skills, ideas, and the value of the handmade. Penland welcomes everyone—from vocational and avocational craft practitioners to interested visitors. Penland is a stimulating, transformative, egalitarian place where people love to work, feel free to experiment, and often exceed their own expectations. Penland’s beautiful location and historic campus inform every aspect of its work. Penland’s Educational Philosophy Penland’s educational philosophy is based on these core ideas: • Total immersion workshop education is a uniquely effective way of learning. • Close interaction with others promotes the exchange of information and ideas between individuals and disciplines. • Generosity enhances education—Penland encourages instructors, students, and staff to freely share their knowledge and experience. • Craft is kept vital by preserving its traditions and constantly expanding its boundaries. Cover Information Front cover: this pot was built by David Steumpfle during his summer workshop. It was glazed and fired by Cynthia Bringle in and sold in the Penland benefit auction for a record price. It is shown in Cynthia’s kiln at her studio at Penland. Inside front cover: chalkboard in the Pines dining room, drawing by instructor Arthur González. Inside back cover: throwing a pot in the clay studio during a workshop taught by Jason Walker. Title page: Instructors Meg Peterson and Mark Angus playing accordion duets during an outdoor Empty Bowls dinner.