Marriage, Knowledge, and Morality Among Catholic Peasants in Northeast Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiocorriere 1977 09

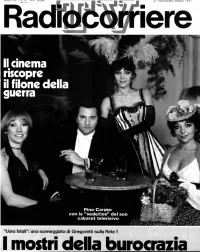

Il cinema riscopre ' il filone della guerra * £ * 'I* Pino Caruso con le “vedettes” del suo cabaret televisivo ”Uova fatali”: uno sceneggiato di Gregoretti sulla Rete 1 I mostri della burocrazia ! In copertina >i /hobby della poesia, è un tulio nel passato, quando già bravo e ancora scono¬ sciuto trovò lavoro e successo come - cabaretiere •; per i telespettatori è SETTIMANALE DELLA RADIO E DELLA TELEVISIONE l'occasione per conoscere il Baga- anno 54 - n. 9 - dal 27 febbraio al 5 marzo 1977 qlmo e la sua storia Nella nostra copertina Pino Caruso con le f rime- donne di Caruso al cabaret. Evelyn Hanack, Laura Troschel e Marma Direttore responsabile: CORRADO GUERZONI Martoglia (Foto di Glauco Cortinì). ALLA TV - UOVA FATALI - DI BULGAKOV domenica 33-39 giovedì 65-71 Una satira sui mostri generati dalla Guida 41-47 venerdì 73-79 burocrazia di Donata Gianeri 12-15 giornaliera lunedi 81-87 Quel senso di farsa culturale martedì 49-55 sabato di Francesca Sanvitale 14-15 radio e TV mercoledì 57-63 Di eroina si continua a morire 16-17 94-95 di Lina Agostini Lettere al direttore 2-4 C'è disco e disco Rubriche 97 L’ITALIA DEGLI ANNI '30 Dalla parte dei piccoli 5 Le nostre pratiche Fu allora che l'italiano diventò conformista Qui il tecnico 98 di Lelio Basso 18-19 Dischi classici 6 Immagini anche inedite di m. a 18 Ottava nota Mondonotizie 99 Piante e fiori Anche la verità storica è un affare Padre Cremona 7 20-22 di Giuseppe Bocconetti 102 Leggiamo insieme 9 Il naturalista Prima di dire si o no di Luciano Arancio 23-24 104 Linea diretta it Dimmi come scrivi UN NUOVO SPETTACOLO CON PINO CARUSO La TV dei ragazzi 31 L’oroscopo 105 Il cabaret dai sotterranei ai riflettori della TV In poltrona 106 e 111 di Gianni De Chiara 2 Come e perché 91 Un comico serissimo con l’hobby della poesia Il medico 92 Moda 108 Affiliato editore: ERI - EDIZIONI RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE ITALIANA alla Federazione direzione e amministrazione: v. -

MASTER THESIS Research Master African Studies 2015-2017 Leiden University/African Studies Center

Photo Jay Garrido Jay Photo (E)motion of saudade The embodiment of solidarity in the Cuban medical cooperation in Mozambique MIRIAM ADELINA OCADIZ ARRIAGA MASTER THESIS Research Master African Studies 2015-2017 Leiden University/African Studies Center First supervisor: Dr. Mayke Kaag Second supervisor: Dr. Kei Otsuki E)motion of saudade. The embodiment of solidarity in the Cuban medical cooperation in Mozambique Miriam A. Ocadiz Arriaga Master Thesis Research Master African Studies 2015-2017 Leiden University/African Studies Center First supervisor: Dr. Mayke Kaag Second supervisor: Dr. Kei Otsuki To my little brother, and to all those who have realized that love is the essence of life, it’s what build bridges through the walls, it´s what shorten abysmal distances, it´s what restore the broken souls, it´s what cures the incurable, it´s what outwits the death Photo Alina Macias Rangel Macias Alina Photo To my little brother, and to all those who have realized that love is the essence of life, it’s what build bridges through the walls, it´s what shorten abysmal distances, it´s what restore the broken souls, it´s what cures the incurable, it´s what outwits the death Copyrights photo; Alina Macias Rangel Index (or the schedule of a journey) Acknowledgments 9 Abstract 13 Preface 15 List of Acronyms 16 1 Introduction. Two ports 17 Human faces 17 Cuban medical cooperation in Mozambique 20 Research question & rationale 23 Order of the thesis 24 2 Methodology. Mapping Nostalgia 27 Methods and methodology 28 Mozambique 30 Cuba 34 Reflection and ethical considerations 36 (Un)Limitations 39 3 Macro perspectives and background. -

Crystal Cruises 2022 Crystal Esprit Atlas

CRYSTAL ESPRIT ® THE CRYSTAL YACHTING LIFESTYLE™ JANUARY 2021 - MARCH 2023 THE ALL-INCLUSIVE WORLD OF CRYSTAL YACHT CRUISES THE CRYSTAL EXPERIENCE® 8 All-Inclusive Luxuries 10 Award-Winning Service 12 Suite Sanctuary 14 Boundless Options 16 A Feast for the Senses 26 Crystal Esprit Overview WORLDWIDE DESTINATIONS 28 Arabia & The Holy Land 34 The Seychelles 36 Adriatic & Aegean Seas CRYSTAL DESTINATION DISCOVERIES™ 46 Shore Excursions EXTEND YOUR JOURNEY 62 Pre- & Post-Cruise Hotel Stays OUR YACHT IS YOUR YACHT 63 Charters, Meetings & Incentives CRYSTAL ESPRIT 64 Deck Plans & Suite Descriptions CRYSTAL PROGRAMMES 68 Before You Sail Guide 74 Ways to Save COVER IMAGE: SANTORINI, GREECE CRYSTAL ESPRIT carefree luxury & easy elegance Luxuriously modern and stylishly nautical, the all-suite, butler-serviced Crystal Esprit enchants with the promise of boutique discovery, customised experiences and welcoming hospitality. On intimate journeys navigating iconic destinations and legendary isles, discover an unparalleled standard of all-inclusive travel defined by friendly camaraderie, superior cuisine, exceptional service and complimentary adventures, both on the water and ashore. The journey of your dreams awaits aboard the Condé Nast Traveler 2019 World’s Best Small Ship Cruise Line. Join us, and fall in love with the Crystal Yachting Lifestyle, Where Luxury is Personal™. — 2021 — CRYSTAL ESPRIT CRUISE CALENDAR 2021 ARABIA & THE HOLY LAND ADRIATIC & IONIAN REFLECTIONS DUBROVNIK TO ATHENS | 7 NIGHTS ARABIAN NIGHTS 10 OCT DUBAI ROUNDTRIP | 6 NIGHTS -

Harold MABERN: Teo MACERO

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Harold MABERN: "Workin' And Wailin'" Virgil Jones -tp,flh; George Coleman -ts; Harold Mabern -p; Buster Williams -b; Leo Morris -d; recorded June 30, 1969 in New York Leo Morris aka Idris Muhammad 101615 A TIME FOR LOVE 4.54 Prest PR7687 101616 WALTZING WESTWARD 9.26 --- 101617 I CAN'T UNDERSTAND WHAT I SEE IN YOU 8.33 --- 101618 STROZIER'S MODE 7.58 --- 101619 BLUES FOR PHINEAS 5.11 --- "Greasy Kid Stuff" Lee Morgan -tp; Hubert Laws -fl,ts; Harold Mabern -p; Boogaloo Joe Jones -g; Buster Williams -b; Idriss Muhammad -d; recorded January 26, 1970 in New York 101620 I WANT YOU BACK 5.30 Prest PR7764 101621 GREASY KID STUFF 8.23 --- 101622 ALEX THE GREAT 7.20 --- 101623 XKE 6.52 --- 101624 JOHN NEELY - BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE 8.33 --- 101625 I HAVEN'T GOT ANYTHING BETTER TO DO 6.04 --- "Remy Martin's New Years Special" James Moody Trio: Harold Mabern -p; Todd Coleman -b; Edward Gladden -d; recorded December 31, 1984 in Sweet Basil, New York it's the rhythm section of James Moody Quartet 99565 YOU DON'T KNOW WHAT LOVE IS 13.59 Aircheck 99566 THERE'S NO GREEATER LOVE 10.14 --- 99567 ALL BLUES 11.54 --- 99568 STRIKE UP THE BAND 13.05 --- "Lookin' On The Bright Side" Harold Mabern -p; Christian McBride -b; Jack DeJohnette -d; recorded February and March 1993 in New York 87461 LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE 5.37 DIW 614 87462 MOMENT'S NOTICE 5.25 --- 87463 BIG TIME COOPER 8.04 --- 87464 AU PRIVAVE -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999

RCA Discography Part 12 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999 LPM/LSP 3700 – Norma Jean Sings Porter Wagoner – Norma Jean [1967] Dooley/Eat, Drink And Be Merry/Country Music Has Gone To Town/Misery Loves Company/Company's Comin'/I've Enjoyed As Much Of This As I Can Stand/Howdy Neighbor, Howdy/I Just Came To Smell The Flowers/A Satisfied Mind/If Jesus Came To Your House/Your Old Love Letters/I Thought I Heard You Calling My Name LPM/LSP 3701 – It Ain’t necessarily Square – Homer and Jethro [1967] Call Me/Lil' Darlin'/Broadway/More/Cute/Liza/The Shadow Of Your Smile/The Sweetest Sounds/Shiny Stockings/Satin Doll/Take The "A" Train LPM/LSP 3702 – Spinout (Soundtrack) – Elvis Presley [1966] Stop, Look And Listen/Adam And Evil/All That I Am/Never Say Yes/Am I Ready/Beach Shack/Spinout/Smorgasbord/I'll Be Back/Tomorrow Is A Long Time/Down In The Alley/I'll Remember You LPM/LSP 3703 – In Gospel Country – Statesmen Quartet [1967] Brighten The Corner Where You Are/Give Me Light/When You've Really Met The Lord/Just Over In The Glory-Land/Grace For Every Need/That Silver-Haired Daddy Of Mine/Where The Milk And Honey Flow/In Jesus' Name, I Will/Watching You/No More/Heaven Is Where You Belong/I Told My Lord LPM/LSP 3704 – Woman, Let Me Sing You a Song – Vernon Oxford [1967] Watermelon Time In Georgia/Woman, Let Me Sing You A Song/Field Of Flowers/Stone By Stone/Let's Take A Cold Shower/Hide/Baby Sister/Goin' Home/Behind Every Good Man There's A Woman/Roll -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861

RCA Discography Part 15 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861 LSP 4600 LSP 4601 – Award Winners – Hank Snow [1971] Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down/I Threw Away The Rose/Ribbon Of Darkness/No One Will Ever Know/Just Bidin' My Time/Snowbird/The Sea Shores Of Old Mexico/Me And Bobby Mcgee/For The Good Times/Gypsy Feet LSP 4602 – Rockin’ – Guess Who [1972] Heartbroken Bopper/Get You Ribbons On/Smoke Big Factory/Arrivederci Girl/Guns, Guns, Guns/Running Bear/Back To The City/Your Nashville Sneakers/Herbert's A Loser/Hi, Rockers: Sea Of Love, Heaven Only Moved Once Yesterday, Don't You Want Me? LSP 4603 – Coat of Many Colors – Dolly Parton [1971] Coat Of Many Colors/Traveling Man/My Blue Tears/If I Lose My Mind/The Mystery Of The Mystery/She Never Met A Man (She Didn't Like)/Early Morning Breeze/The Way I See You/Here I Am/A Better Place To Live LSP 4604 – First 15 Years – Hank Locklin [1971]Please Help Me/Send Me the Pillow You Dream On/I Don’t Apologize/Release Me/Country Hall of Fame/Before the Next Teardrop Falls/Danny Boy/Flying South/Anna (With Nashville Brass)/Happy Journey LSP 4605 – Charlotte Fever – Kenny Price [1971] Charlotte Fever/You Can't Take It With You/Me And You And A Dog Named Boo/Ruby (Are You Mad At Your Man)/She Cried/Workin' Man Blues/Jody And The Kid/Destination Anywhere/For The Good Times/Super Sideman LSP 4606 – Have You Heard Dottie West – Dottie West [1971] You're The Other Half Of Me/Just One Time/Once You Were Mine/Put Your Hand -

Stanley Turrentine Sugar Mp3, Flac, Wma

Stanley Turrentine Sugar mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Sugar Country: US Released: 1971 Style: Soul-Jazz, Post Bop, Modal MP3 version RAR size: 1222 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1634 mb WMA version RAR size: 1534 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 739 Other Formats: WMA DXD ADX VOC DMF AIFF FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Sugar A1 10:00 Written-By – Stanley Turrentine Sunshine Alley A2 11:00 Written-By – Butch Cornell Impressions B 15:30 Written-By – John Coltrane Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Pressed By – Columbia Records Pressing Plant, Terre Haute Published By – Stanshirl Publishing Co. Published By – Daahoud Music Co. Published By – Jowcol Music Credits Bass – Ron Carter Congas – Richard "Pablo" Landrum* Design [Album] – Elton Robinson Drums – Billy Kaye Electric Piano – Lonnie L. Smith, Jr.* Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Guitar – George Benson Liner Notes – Ira Gitler Mastered By – Van Gelder* Organ – Butch Cornell Photography By [Cover Photographs] – Pete Turner Photography By [Liner Photographs] – Chuck Stewart Producer – Creed Taylor Tenor Saxophone – Stanley Turrentine Trumpet – Freddie Hubbard Notes Green CTI labels. Recorded at Van Gelder Studios Recorded November, 1970 Publishing Credits: Track A1: Stanshirl Publ. Co. Track A2: Daahoud Music Co. Track B: Jowcol Music All selections BMI Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: BMI Matrix / Runout (Side A Label): RVG 87658 A Matrix / Runout (Side B Label): RVG 87658 B Matrix / Runout (Side A Etching): RVG•87658•A• Matrix -

The Curving Shore of Time and Space: Notes on the Prologue to Pushkin's Ruslan and Ludmila

The Curving Shore of Time and Space: Notes on the Prologue to Pushkin’s Ruslan and Ludmila The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Russell, James R. 2012. The Curving Shore of Time and Space: Notes on the Prologue to Pushkin’s Ruslan and Ludmila. In Shoshannat Yaakov: Jewish and Iranian Studies in Honor of Yaakov Elman, ed. Shai Secunda and Steven Fine, 323–370. Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. Published Version doi:10.1163/9789004235458_018 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34257918 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP 1 THE CURVING SHORE OF TIME AND SPACE: NOTES ON THE PROLOGUE TO PUSHKIN’S RUSLAN AND LUDMILA. By James R. Russell, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Золотое руно, где же ты, золотое руно? Всю дорогу шумели морские тяжёлые волны, И, покинув корабль, натрудивший в морях полотно, Одиссей возвратился, пространством и временем полный! (“Golden fleece, where are you now, golden fleece? All the journey long roared the heavy sea waves, And, leaving the ship that had worked a canvas of the seas, Odysseus returned, replete with time and space!”) —Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938).1 “As lucid as you like or as deep as you choose to dive.” —Adam Gopnik, on the Alice books of Lewis Carroll.2 PREFACE. -

The Life and Music of Mccoy Tyner

THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF MCCOY TYNER AN EXAMINATION OF THE SOCIOCULTURAL INFLUENCES ON MCCOY TYNER AND HIS MUSIC by Alton Louis Merrell II Bachelor of Music, Youngstown State University, 2000 Master of Music, Youngstown State University, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Alton Louis Merrell II It was defended on March 28, 2013 Committee Members: Mathew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Department of Music Laurence Glasco, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of History Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Nathan Davis, PhD, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Alton Louis Merrell II 2013 iii Nathan T. Davis, PhD THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF MCCOY TYNER: AN EXAMINATION OF THE SOCIOCULTURAL INFLUENCES ON MCCOY TYNER AND HIS MUSIC Alton Louis Merrell II, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This study is a historical, sociocultural and analytical examination of McCoy Tyner’s life and music. McCoy Tyner is a preeminent voice in the history of modern jazz piano performance, and his style is not only one of the most recognizable in jazz history, it has been studied and assimilated into the musical vocabulary of renowned pianists worldwide. Although Tyner’s influence is vast, there is a paucity of research on how he achieved his signature style, and the sociocultural and musical influences that cultivated his early musical talent and signature piano style have not been researched. -

Coral Reef Restoration Toolkit a Field-Oriented Guide Developed in the Seychelles Islands

Coral Reef Restoration Toolkit A Field-Oriented Guide Developed in the Seychelles Islands EDITED BY SARAH FRIAS-TORRES, PHANOR H MONTOYA-MAYA, AND NIRMAL SHAH A. DUNAND i Coral Reef Restoration Toolkit A Field-Oriented Guide Developed in the Seychelles Islands Editors Sarah Frias-Torres 1,2,3, Phanor H Montoya-Maya 1, 4, Nirmal Shah 1 1 Nature Seychelles, The Centre for Environment & Education, Roche Caiman, Mahe, Republic of Seychelles 2 Smithsonian Marine Station, 701 Seaway Drive, Fort Pierce, FL 34949 USA 3 Vulcan Inc., 505 5th Avenue South, Seattle WA 98104 USA 4 Corales de Paz, Calle 4 No. 35A-51, Cali, Colombia Contributors Paul Anstey, Nature Seychelles, Republic of Seychelles Gilles-David Derand, BirdLife International, La Reunion (France) Calum Ferguson, Republic of Seychelles Sarah Frias-Torres, Nature Seychelles, Republic of Seychelles Joseph Marlow, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand Paul McCann, Trojan Diving Services, Australia Phanor H Montoya-Maya, Nature Seychelles, Republic of Seychelles / Corales de Paz, Colombia Claude Reveret, CREOCEAN, France Katherine Rowe, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Saudi Arabia Chloe Shute, Nature Seychelles, Republic of Seychelles Derek Soto, University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico Acknowledgements Expert advice from several colleagues has aided the development of the Toolkit. We particularly thank Kaylee Smit and Sofie Klaus-Caan for their helpful and constructive reviews. This Tookit was tested on a live audience attending the first Reef Rescuers Training Program in Coral Reef Restoration at Nature Seychelles, Praslin, Republic of Seychelles in June-August 2015. The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for their contributions to early drafts of this Toolkit: Danielle M Becker, Tamsen T Byfield, Austin Laing-Herbert, Louise Malaise, Ron Kirby Bugay Manit, Tess Moriarty. -

The Henry Mancini Collection, 1955-1969

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6h4nb3v9 No online items Finding Aid for the Henry Mancini Collection, 1955-1969 Processed by Stephen Davison; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library UCLA Library Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities --Performing Arts --MusicArts and Humanities --Film, Television and BroadcastingGeographical (By Place) --United States (excluding California)Geographical (By Place) --California --Los Angeles Area Finding Aid for the Henry Mancini PASC-M 18 1 Collection, 1955-1969 Finding Aid for the Henry Mancini Collection, 1955-1969 Collection number: PASC-M 18 UCLA Library Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library UCLA Library Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: Stephen Davison Date Completed: 1996 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: The Henry Mancini Collection, Date (inclusive): 1955-1969 Collection number: PASC-M 18 Creator: Mancini, Henry Extent: 20 boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. UCLA Library Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Shelf location: Held at SRLF; use MC4147685 for paging purposes. -

The Turkish Language Explained for English Speakers: a Treatise on The

The Turkish Language Explained for English Speakers A Treatise on the Turkish Language and its Grammar. John Guise Title: The Turkish Language Explained for English Speakers. Description: A Treatise on the Turkish Language and its Grammar. Updated: August 2015 ISBN 978-0-473-20817-2 Copyright: 2012 John Guise. All rights reserved. http://www.turkishlanguage.co.uk Table of Contents The Turkish Language Explained for English Speakers Foreword Ch. 1 : About the Turkish Language. Ch. 2 : Vowel Harmony Ch. 3 : Consonant Mutation Ch. 4 : Buffer Letters Ch. 5 : The Suffixes Ch. 6 : The Articles Ch. 7 : Nouns Ch. 8 : Adjectives Ch. 9 : Personal Pronouns Ch. 10 : Possessive Adjectives Ch. 11 : The Possessive Relationship Ch. 12 : Possessive Constructions Ch. 13 : Possession Var and Yok Ch. 14 : Verbs The Infinitive Ch. 15 : The Verb "To be" Ch. 16 : Present Continuous Tense Ch. 17 : Simple Tense Positive Ch. 18 : Simple Tense Negative Ch. 19 : Future Tense Ch. 20 : Past Tense Ch. 21 : The Conditional Mood Ch. 22 : Auxiliary Verbs Ch. 23 : The Imperative Mood Ch. 24 : The Co‑operative Mood Ch. 25 : The Passive Mood Ch. 26 : The Causative Mood Ch. 27 : The Mood of Obligation Ch. 28 : The Potential Mood Ch. 29 : The Mood of Wish and Desire Ch. 30 : Verbal Adjectives and Nouns Ch. 31 : Object Participles Ch. 32 : İken "while" Ch. 33 : Verbal Nouns Ch. 34 : Adverbial Clauses Ch. 35 : Ki "that, which, who" Ch. 36 : Demonstratives Ch. 37 : Spatials Ch. 38 : Spatial Relationships Ch. 39 : Time and Seasons Ch. 40 : Colours Ch. 41 : Numbers Ch. 42 : Word Recognition in Turkish Ch.