The Life and Music of Mccoy Tyner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Jazz Lines Publications

Jazz Lines Publications Presents sweet honey bee Arranged by duke pearson transcribed and Prepared by Dylan Canterbury full score jlp-7330 Music by Duke Pearson Copyright © 1965 Gailancy Music International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2015 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. This Arrangement Has Been Published with the Authorization of the Estate of Duke Pearson. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA duke pearson series sweet honey bee (1966) Background: Duke Pearson was an important pianist, composer, arranger and producer during the 1960s and 1970s. He was born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1932 and played trumpet as well as piano with many local groups. After attending Clark College, he toured with Tab Smith and Little Willie John before he moved to New York City in January of 1959. Donald Byrd heard him, and Byrd was the leader of Pearson’s first recording session. Soon Pearson was playing with the Benny Golson-Art Farmer Jazztet. Pearson became the musical director for Nancy Wilson, as well as continuing to tour and record with Donald Byrd. In 1963, Blue Note Records producer and musical director Ike Quebec passed away, and Pearson became Blue Note’s A&R director, as well as make his own albums. Grant Green, Stanley Turrentine, Johnny Coles, Blue Mitchell, Hank Mobley, Bobby Hutcherson, Lee Morgan and Lou Donaldson all benefited from his arranging and producing skills. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1492 HON. DENNIS J. KUCINICH HON. DALE E. KILDEE HON. ROBERT HURT HON. DENNIS J

E1492 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks September 12, 2012 sharing the stage with Coleman Hawkins, 2010 resignation. In 2009, he retired as Dep- RECOGNIZING VIRGINIA Slam Stewart, and Erroll Garner. One of the uty Court Administrator of Ohio’s Eighth Dis- INDUSTRIES FOR THE BLIND earliest of Mr. Heath’s own big bands (1947– trict Court of Appeals in order to fulfill a cam- 48) in Philadelphia included John Coltrane, paign promise for his election to the Cuyahoga HON. ROBERT HURT Benny Golson, Specs Wright, Cal Massey, County Council. OF VIRGINIA Johnny Coles, Ray Bryant, and Nelson Boyd. Councilman Gallagher was elected to the IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES He also played with and composed for Dizzy Wednesday, September 12, 2012 Gillespie, Miles Davis, Kenny Dorham, Milt Cuyahoga County Council in 2010 and is now Jackson, and Art Blakey. During his career, the Chair of the Public Safety Committee. Mr. HURT. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to rec- Mr. Heath has performed on more than 100 Some of his achievements outside of public ognize Virginia Industries for the Blind, an record albums, including 7 with The Heath office include his membership in the Ability One organization that began in Char- Brothers and 12 as a leader. He has also writ- Strongsville Rotary Club and Strongsville lottesville that empowers blind and visually im- ten more than 125 compositions, many of Chamber of Commerce. He has served as a paired Virginians in achieving their maximum which have become jazz standards, including Trustee on the Hospital Board of Southwest level of employment and career development. -

Booker Little

1 The TRUMPET of BOOKER LITTLE Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 11, 2020 2 Born: Memphis, April 2, 1938 Died: NYC. Oct. 5, 1961 Introduction: You may not believe this, but the vintage Oslo Jazz Circle, firmly founded on the swinging thirties, was very interested in the modern trends represented by Eric Dolphy and through him, was introduced to the magnificent trumpet playing by the young Booker Little. Even those sceptical in the beginning gave in and agreed that here was something very special. History: Born into a musical family and played clarinet for a few months before taking up the trumpet at the age of 12; he took part in jam sessions with Phineas Newborn while still in his teens. Graduated from Manassas High School. While attending the Chicago Conservatory (1956-58) he played with Johnny Griffin and Walter Perkins’s group MJT+3; he then played with Max Roach (June 1958 to February 1959), worked as a freelancer in New York with, among others, Mal Waldron, and from February 1960 worked again with Roach. With Eric Dolphy he took part in the recording of John Coltrane’s album “Africa Brass” (1961) and led a quintet at the Five Spot in New York in July 1961. Booker Little’s playing was characterized by an open, gentle tone, a breathy attack on individual notes, a nd a subtle vibrato. His soli had the brisk tempi, wide range, and clean lines of hard bop, but he also enlarged his musical vocabulary by making sophisticated use of dissonance, which, especially in his collaborations with Dolphy, brought his playing close to free jazz. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Album Covers Through Jazz

SantiagoAlbum LaRochelle Covers Through Jazz Album covers are an essential part to music as nowadays almost any project or single alike will be accompanied by album artwork or some form of artistic direction. This is the reality we live with in today’s digital age but in the age of vinyl this artwork held even more power as the consumer would not only own a physical copy of the music but a 12’’ x 12’’ print of the artwork as well. In the 40’s vinyl was sold in brown paper sleeves with the artists’ name printed in black type. The implementation of artwork on these vinyl encasings coincided with years of progress to be made in the genre as a whole, creating a marriage between the two mediums that is visible in the fact that many of the most acclaimed jazz albums are considered to have the greatest album covers visually as well. One is not responsible for the other but rather, they each amplify and highlight each other, both aspects playing a role in the artistic, musical, and historical success of the album. From Capitol Records’ first artistic director, Alex Steinweiss, and his predecessor S. Neil Fujita, to all artists to be recruited by Blue Note Records’ founder, Alfred Lion, these artists laid the groundwork for the role art plays in music today. Time Out Sadamitsu "S. Neil" Fujita Recorded June 1959 Columbia Records Born in Hawaii to japanese immigrants, Fujita began studying art Dave Brubeck- piano Paul Desmond- alto sax at an early age through his boarding school. -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

Lee Morgan and the Philadelphia Jazz Scene of the 1950S

A Musical Education: Lee Morgan and the Philadelphia Jazz Scene of the 1950s Byjeffery S. McMillan The guys were just looking at him. They couldn't believe what was coming out of that horn! You know, ideas like . where would you get them? Michael LaVoe (1999) When Michael LaVoe observed Lee Morgan, a fellow freshman at Philadelphia's Mastbaum Vocational Technical High School, playing trumpet with members of the school's dance band in the first days of school in September 1953, he could not believe his ears. Morgan, who had just turned fifteen years old the previous July, had remarkable facility on his instrument and displayed a sophisticated understanding of music for someone so young. Other members of the ensemble, some of whom al- ready had three years of musical training and performing experience in the school's vocational music program, experienced similar feelings of dis- belief when they heard the newcomer's precocious ability. Lee Morgan had successfully auditioned into Mastbaum's music program, the strongest of its kind in Philadelphia from the 1930s through the 1960s, and demon- strated a rare ability that begged the title "prodigy." Almost exactly three years later, in November of 1956, Lee Morgan, now a member of die Dizzy Gillespie orchestra, elicited a similar response at the professional level after the band's New York opening at Birdland. Word spread, and as the Gillespie band embarked on its national tour, au- diences and critics nationwide took notice of the young soloist featured on what was often the leader's showcase number: "A Night in Tunisia." Nat Hentoff caught the band on their return to New York from the Midwest in 1957. -

From King Records Month 2018

King Records Month 2018 = Unedited Tweets from Zero to 180 Aug. 3, 2018 Zero to 180 is honored to be part of this year's celebration of 75 Years of King Records in Cincinnati and will once again be tweeting fun facts and little known stories about King Records throughout King Records Month in September. Zero to 180 would like to kick off things early with a tribute to King session drummer Philip Paul (who you've heard on Freddy King's "Hideaway") that is PACKED with streaming audio links, images of 45s & LPs from around the world, auction prices, Billboard chart listings and tons of cool history culled from all the important music historians who have written about King Records: “Philip Paul: The Pulse of King” https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=32149 Aug. 22, 2018 King Records Month is just around the corner - get ready! Zero to 180 will be posting a new King history piece every 3 days during September as well as October. There will also be tweeting lots of cool King trivia on behalf of Xavier University's 'King Studios' historic preservation collaborative - a music history explosion that continues with this baseball-themed celebration of a novelty hit that dominated the year 1951: LINK to “Chew Tobacco Rag” Done R&B (by Lucky Millinder Orchestra) https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=27158 Aug. 24, 2018 King Records helped pioneer the practice of producing R&B versions of country hits and vice versa - "Chew Tobacco Rag" (1951) and "Why Don't You Haul Off and Love Me" (1949) being two examples of such 'crossover' marketing. -

Debut Label Discography

Début Label discography Début was established in 1951 by Charles Mingus and possibly others. It was located at 4364 Bryon Avenue in New York City in 1952, relocated to the Grand Central Station in 1954. By 1956 it was located at 331 West 51st Street. Début recorded jazz and pop music. Fantasy Records acquired the Début Catalog in the early 1960’s. This Debut Label discography was compiled using Schwann catalogs from 1950 to 1957, The Jazz Discography Project Website (http://www.jazzdisco.org) and The American Record Label Directory and Dating Guide, 1940-1959 by Galen Gart, 10 Inch Series DLP-1 - Strings and Keys - Charles Mingus [1951] Body and Soul/Blue Moon/Blue Tide/What Is This Thing Called Love/Darn That Dream/Yesterdays DLP-2 - Jazz at Massey Hall Volume 1- Quintet - Various Artists [1952] Perdido/Salt Peanuts//Salt Peanuts Continued/All the Things You Are DLP-3 - Jazz at Massey Hall Volume 2 - Bud Powell [1952] Embraceable You/Sure Thing/Cherokee//Jubilee/Lullabye of Birdland/Basically Speaking DLP-4 - Jazz at Massey Hall Volume 3 - Charles Mingus [1952] Wee//Hot House/A Night in Tunisia DLP-5 - Jazz Workshop Volume 1-Trombone Rapport - J.J. Johnson, Kai Winding, Benny Green & Willie Dennis [1953] Move/Stardust//Yesterdays DLP-6 - Explorations - Ted Macero [1954] Teo/I’ll Remember April/How Low the Earth//Mitzi/Yesterdays/Explorations DLP-7 - Introducing Paul Bley - Paul Bley With Art Blakey and Charles Mingus [1954] Opus 1/Teapot/Like Someone In Love//Spontaneous Combustion/Split Kick/Can’t Get Started DLP-8 - The New Oscar Pettiford -

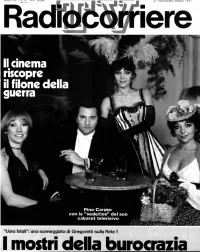

Radiocorriere 1977 09

Il cinema riscopre ' il filone della guerra * £ * 'I* Pino Caruso con le “vedettes” del suo cabaret televisivo ”Uova fatali”: uno sceneggiato di Gregoretti sulla Rete 1 I mostri della burocrazia ! In copertina >i /hobby della poesia, è un tulio nel passato, quando già bravo e ancora scono¬ sciuto trovò lavoro e successo come - cabaretiere •; per i telespettatori è SETTIMANALE DELLA RADIO E DELLA TELEVISIONE l'occasione per conoscere il Baga- anno 54 - n. 9 - dal 27 febbraio al 5 marzo 1977 qlmo e la sua storia Nella nostra copertina Pino Caruso con le f rime- donne di Caruso al cabaret. Evelyn Hanack, Laura Troschel e Marma Direttore responsabile: CORRADO GUERZONI Martoglia (Foto di Glauco Cortinì). ALLA TV - UOVA FATALI - DI BULGAKOV domenica 33-39 giovedì 65-71 Una satira sui mostri generati dalla Guida 41-47 venerdì 73-79 burocrazia di Donata Gianeri 12-15 giornaliera lunedi 81-87 Quel senso di farsa culturale martedì 49-55 sabato di Francesca Sanvitale 14-15 radio e TV mercoledì 57-63 Di eroina si continua a morire 16-17 94-95 di Lina Agostini Lettere al direttore 2-4 C'è disco e disco Rubriche 97 L’ITALIA DEGLI ANNI '30 Dalla parte dei piccoli 5 Le nostre pratiche Fu allora che l'italiano diventò conformista Qui il tecnico 98 di Lelio Basso 18-19 Dischi classici 6 Immagini anche inedite di m. a 18 Ottava nota Mondonotizie 99 Piante e fiori Anche la verità storica è un affare Padre Cremona 7 20-22 di Giuseppe Bocconetti 102 Leggiamo insieme 9 Il naturalista Prima di dire si o no di Luciano Arancio 23-24 104 Linea diretta it Dimmi come scrivi UN NUOVO SPETTACOLO CON PINO CARUSO La TV dei ragazzi 31 L’oroscopo 105 Il cabaret dai sotterranei ai riflettori della TV In poltrona 106 e 111 di Gianni De Chiara 2 Come e perché 91 Un comico serissimo con l’hobby della poesia Il medico 92 Moda 108 Affiliato editore: ERI - EDIZIONI RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE ITALIANA alla Federazione direzione e amministrazione: v.