The First Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiocorriere 1977 09

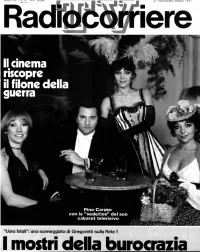

Il cinema riscopre ' il filone della guerra * £ * 'I* Pino Caruso con le “vedettes” del suo cabaret televisivo ”Uova fatali”: uno sceneggiato di Gregoretti sulla Rete 1 I mostri della burocrazia ! In copertina >i /hobby della poesia, è un tulio nel passato, quando già bravo e ancora scono¬ sciuto trovò lavoro e successo come - cabaretiere •; per i telespettatori è SETTIMANALE DELLA RADIO E DELLA TELEVISIONE l'occasione per conoscere il Baga- anno 54 - n. 9 - dal 27 febbraio al 5 marzo 1977 qlmo e la sua storia Nella nostra copertina Pino Caruso con le f rime- donne di Caruso al cabaret. Evelyn Hanack, Laura Troschel e Marma Direttore responsabile: CORRADO GUERZONI Martoglia (Foto di Glauco Cortinì). ALLA TV - UOVA FATALI - DI BULGAKOV domenica 33-39 giovedì 65-71 Una satira sui mostri generati dalla Guida 41-47 venerdì 73-79 burocrazia di Donata Gianeri 12-15 giornaliera lunedi 81-87 Quel senso di farsa culturale martedì 49-55 sabato di Francesca Sanvitale 14-15 radio e TV mercoledì 57-63 Di eroina si continua a morire 16-17 94-95 di Lina Agostini Lettere al direttore 2-4 C'è disco e disco Rubriche 97 L’ITALIA DEGLI ANNI '30 Dalla parte dei piccoli 5 Le nostre pratiche Fu allora che l'italiano diventò conformista Qui il tecnico 98 di Lelio Basso 18-19 Dischi classici 6 Immagini anche inedite di m. a 18 Ottava nota Mondonotizie 99 Piante e fiori Anche la verità storica è un affare Padre Cremona 7 20-22 di Giuseppe Bocconetti 102 Leggiamo insieme 9 Il naturalista Prima di dire si o no di Luciano Arancio 23-24 104 Linea diretta it Dimmi come scrivi UN NUOVO SPETTACOLO CON PINO CARUSO La TV dei ragazzi 31 L’oroscopo 105 Il cabaret dai sotterranei ai riflettori della TV In poltrona 106 e 111 di Gianni De Chiara 2 Come e perché 91 Un comico serissimo con l’hobby della poesia Il medico 92 Moda 108 Affiliato editore: ERI - EDIZIONI RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE ITALIANA alla Federazione direzione e amministrazione: v. -

Marriage, Knowledge, and Morality Among Catholic Peasants in Northeast Brazil

Marriage, knowledge, and morality among Catholic peasants in Northeast Brazil Maya Miranda Mayblin London School of Economics and Political Science PhD in Anthropology 2005 1 UMI Number: U202031 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U202031 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 "777 £ f B m w i' , \> .- fcconomic awerxx; (b<c b t ° tO Abstract This thesis is an ethnographic study of marriage, religious practice, and concepts of morality among a group of peasant farmers in Northeast Brazil. It investigates how, over the individual life-course, concepts of moral accountability develop and change, and how people negotiate such changes through specific discourses on labour and suffering. Such discourses stem from a particularised Catholic ideology which grows out of the social and economic history of the region. The existential problem of living both morally and productively in the world manifests itself most explicitly in local understandings of marriage; revealing a perceived tension between the states of innocence and knowledge. The thesis shows how this tension feeds into a heightened concern over the various stages of transformation in a person’s life, particularly the transformation from childhood to adolescence. -

MASTER THESIS Research Master African Studies 2015-2017 Leiden University/African Studies Center

Photo Jay Garrido Jay Photo (E)motion of saudade The embodiment of solidarity in the Cuban medical cooperation in Mozambique MIRIAM ADELINA OCADIZ ARRIAGA MASTER THESIS Research Master African Studies 2015-2017 Leiden University/African Studies Center First supervisor: Dr. Mayke Kaag Second supervisor: Dr. Kei Otsuki E)motion of saudade. The embodiment of solidarity in the Cuban medical cooperation in Mozambique Miriam A. Ocadiz Arriaga Master Thesis Research Master African Studies 2015-2017 Leiden University/African Studies Center First supervisor: Dr. Mayke Kaag Second supervisor: Dr. Kei Otsuki To my little brother, and to all those who have realized that love is the essence of life, it’s what build bridges through the walls, it´s what shorten abysmal distances, it´s what restore the broken souls, it´s what cures the incurable, it´s what outwits the death Photo Alina Macias Rangel Macias Alina Photo To my little brother, and to all those who have realized that love is the essence of life, it’s what build bridges through the walls, it´s what shorten abysmal distances, it´s what restore the broken souls, it´s what cures the incurable, it´s what outwits the death Copyrights photo; Alina Macias Rangel Index (or the schedule of a journey) Acknowledgments 9 Abstract 13 Preface 15 List of Acronyms 16 1 Introduction. Two ports 17 Human faces 17 Cuban medical cooperation in Mozambique 20 Research question & rationale 23 Order of the thesis 24 2 Methodology. Mapping Nostalgia 27 Methods and methodology 28 Mozambique 30 Cuba 34 Reflection and ethical considerations 36 (Un)Limitations 39 3 Macro perspectives and background. -

Crystal Cruises 2022 Crystal Esprit Atlas

CRYSTAL ESPRIT ® THE CRYSTAL YACHTING LIFESTYLE™ JANUARY 2021 - MARCH 2023 THE ALL-INCLUSIVE WORLD OF CRYSTAL YACHT CRUISES THE CRYSTAL EXPERIENCE® 8 All-Inclusive Luxuries 10 Award-Winning Service 12 Suite Sanctuary 14 Boundless Options 16 A Feast for the Senses 26 Crystal Esprit Overview WORLDWIDE DESTINATIONS 28 Arabia & The Holy Land 34 The Seychelles 36 Adriatic & Aegean Seas CRYSTAL DESTINATION DISCOVERIES™ 46 Shore Excursions EXTEND YOUR JOURNEY 62 Pre- & Post-Cruise Hotel Stays OUR YACHT IS YOUR YACHT 63 Charters, Meetings & Incentives CRYSTAL ESPRIT 64 Deck Plans & Suite Descriptions CRYSTAL PROGRAMMES 68 Before You Sail Guide 74 Ways to Save COVER IMAGE: SANTORINI, GREECE CRYSTAL ESPRIT carefree luxury & easy elegance Luxuriously modern and stylishly nautical, the all-suite, butler-serviced Crystal Esprit enchants with the promise of boutique discovery, customised experiences and welcoming hospitality. On intimate journeys navigating iconic destinations and legendary isles, discover an unparalleled standard of all-inclusive travel defined by friendly camaraderie, superior cuisine, exceptional service and complimentary adventures, both on the water and ashore. The journey of your dreams awaits aboard the Condé Nast Traveler 2019 World’s Best Small Ship Cruise Line. Join us, and fall in love with the Crystal Yachting Lifestyle, Where Luxury is Personal™. — 2021 — CRYSTAL ESPRIT CRUISE CALENDAR 2021 ARABIA & THE HOLY LAND ADRIATIC & IONIAN REFLECTIONS DUBROVNIK TO ATHENS | 7 NIGHTS ARABIAN NIGHTS 10 OCT DUBAI ROUNDTRIP | 6 NIGHTS -

Harold MABERN: Teo MACERO

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Harold MABERN: "Workin' And Wailin'" Virgil Jones -tp,flh; George Coleman -ts; Harold Mabern -p; Buster Williams -b; Leo Morris -d; recorded June 30, 1969 in New York Leo Morris aka Idris Muhammad 101615 A TIME FOR LOVE 4.54 Prest PR7687 101616 WALTZING WESTWARD 9.26 --- 101617 I CAN'T UNDERSTAND WHAT I SEE IN YOU 8.33 --- 101618 STROZIER'S MODE 7.58 --- 101619 BLUES FOR PHINEAS 5.11 --- "Greasy Kid Stuff" Lee Morgan -tp; Hubert Laws -fl,ts; Harold Mabern -p; Boogaloo Joe Jones -g; Buster Williams -b; Idriss Muhammad -d; recorded January 26, 1970 in New York 101620 I WANT YOU BACK 5.30 Prest PR7764 101621 GREASY KID STUFF 8.23 --- 101622 ALEX THE GREAT 7.20 --- 101623 XKE 6.52 --- 101624 JOHN NEELY - BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE 8.33 --- 101625 I HAVEN'T GOT ANYTHING BETTER TO DO 6.04 --- "Remy Martin's New Years Special" James Moody Trio: Harold Mabern -p; Todd Coleman -b; Edward Gladden -d; recorded December 31, 1984 in Sweet Basil, New York it's the rhythm section of James Moody Quartet 99565 YOU DON'T KNOW WHAT LOVE IS 13.59 Aircheck 99566 THERE'S NO GREEATER LOVE 10.14 --- 99567 ALL BLUES 11.54 --- 99568 STRIKE UP THE BAND 13.05 --- "Lookin' On The Bright Side" Harold Mabern -p; Christian McBride -b; Jack DeJohnette -d; recorded February and March 1993 in New York 87461 LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE 5.37 DIW 614 87462 MOMENT'S NOTICE 5.25 --- 87463 BIG TIME COOPER 8.04 --- 87464 AU PRIVAVE -

The Case of Kisite Marine National Park and Mpunguti Marine National Reserve, Kenya

IUCN Eastern Africa Programme Economics Programme and Marine & Coastal Programme Economic Constraints to the Management of Marine Protected Areas: the Case of Kisite Marine National Park and Mpunguti Marine National Reserve, Kenya Lucy Emerton and Yemi Tessema May 2001 IUCN Eastern Africa Regional Office Economic Constraints to the Management of Economics Programme and Marine & Coastal Programme Marine Protected Areas: the Case of Kisite Marine National Park and Mpunguti Marine National Reserve, Kenya Lucy Emerton and Yemi Tessema May 2001 The text is printed on Diamond Matt Art Paper, made from sugarcane waste, recycled paper and totally chlorine free pulp. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The case study relied heavily on the support of Dr. Rod Salm, the then IUCN EARO Marine and Coastal Programme Co-ordinator; Ms. Sue Wells, the current IUCN EARO Marine and Coastal Programme Co-ordinator; Dr. Nyawira Muthiga, KWS Head, Coastal and Wetlands Programme, Ms. Janet Kaleha, Kisite Marine National Park Warden; Mr. Simba Mwabuzi, KWS Coxswain; Mr. Etyang, Kwale District Fisheries Officer; the Assistant Chief, Elders and residents of Mkwiro, Shimoni and Wasini Villages; and the private hoteliers and tour operators of the Shimoni-Wasini area. Additional thanks go to Gordon Arara and other staff of IUCN-EARO who assisted with production of this report. PREFACE This document was produced in response to a growing interest by environment and wildlife agencies in Eastern Africa in addressing issues relating to the financial and economic sustainability of MPAs, and to their increasing recognition that economic and financial measures form important tools in MPA management. This study is intended to document practical lessons learned, and to highlight needs and niches for the use of economic and financial tools for MPA management in the region. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999

RCA Discography Part 12 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999 LPM/LSP 3700 – Norma Jean Sings Porter Wagoner – Norma Jean [1967] Dooley/Eat, Drink And Be Merry/Country Music Has Gone To Town/Misery Loves Company/Company's Comin'/I've Enjoyed As Much Of This As I Can Stand/Howdy Neighbor, Howdy/I Just Came To Smell The Flowers/A Satisfied Mind/If Jesus Came To Your House/Your Old Love Letters/I Thought I Heard You Calling My Name LPM/LSP 3701 – It Ain’t necessarily Square – Homer and Jethro [1967] Call Me/Lil' Darlin'/Broadway/More/Cute/Liza/The Shadow Of Your Smile/The Sweetest Sounds/Shiny Stockings/Satin Doll/Take The "A" Train LPM/LSP 3702 – Spinout (Soundtrack) – Elvis Presley [1966] Stop, Look And Listen/Adam And Evil/All That I Am/Never Say Yes/Am I Ready/Beach Shack/Spinout/Smorgasbord/I'll Be Back/Tomorrow Is A Long Time/Down In The Alley/I'll Remember You LPM/LSP 3703 – In Gospel Country – Statesmen Quartet [1967] Brighten The Corner Where You Are/Give Me Light/When You've Really Met The Lord/Just Over In The Glory-Land/Grace For Every Need/That Silver-Haired Daddy Of Mine/Where The Milk And Honey Flow/In Jesus' Name, I Will/Watching You/No More/Heaven Is Where You Belong/I Told My Lord LPM/LSP 3704 – Woman, Let Me Sing You a Song – Vernon Oxford [1967] Watermelon Time In Georgia/Woman, Let Me Sing You A Song/Field Of Flowers/Stone By Stone/Let's Take A Cold Shower/Hide/Baby Sister/Goin' Home/Behind Every Good Man There's A Woman/Roll -

Seascape Strategy for Building Social, Economic, and Ecological Resilience

SEASCAPE STRATEGY FOR BUILDING SOCIAL, ECONOMIC, AND ECOLOGICAL RESILIENCE SHIMONI-VANGA SEASCAPE SGP KENYA OCTOBER 2018 COSTAL AND MARINE RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KWALE Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY During GEF SGP’s Sixth Operational Phase (GEF-6), SGP Kenya has adopted a landscape management approach, aiming to enable community-based organizations to take collective action towards adaptive landscape and seascape management promoting socio-ecological resilience. The Shimoni-Vanga Seascape located at the southern coast of Kenya (Kwale County) is endowed with rich biodiversity and a relatively undisturbed ecosystem. The seascape boasts a biodiversity rich Marine Protected Area with a high potential for productivity from the adjacent co-management areas. The seascape area supports livelihoods of the communities that live and depend on it. These communities also include some of the indigenous groups recognized by the World Bank as marginalized and vulnerable, such as the Wakifundi (around Shimoni) and Wachwaka (around Kibuyuni) and recently citizenized 43rd Kenyan tribe the “Makondes from Mozambique”. These groups participate in tourist activities, seaweed farming and fishing. Despite the low level of education, these groups have a strong cultural attachment to the sea and would benefit from interventions of the projects. With the seascape being relatively pristine compared to other degraded coastal areas in Kenya, sustaining seascape resilience is paramount. Based on baseline information collected in preparation of this Landscape Strategy, resilience of the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape can be enhanced through the following Landscape Outcomes: 1. Ensuring that the integrity of habitats and biodiversity within the seascape is enhanced; 2. Reduction of pressure on mangrove resources from domestic and commercial usage; 3. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861

RCA Discography Part 15 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861 LSP 4600 LSP 4601 – Award Winners – Hank Snow [1971] Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down/I Threw Away The Rose/Ribbon Of Darkness/No One Will Ever Know/Just Bidin' My Time/Snowbird/The Sea Shores Of Old Mexico/Me And Bobby Mcgee/For The Good Times/Gypsy Feet LSP 4602 – Rockin’ – Guess Who [1972] Heartbroken Bopper/Get You Ribbons On/Smoke Big Factory/Arrivederci Girl/Guns, Guns, Guns/Running Bear/Back To The City/Your Nashville Sneakers/Herbert's A Loser/Hi, Rockers: Sea Of Love, Heaven Only Moved Once Yesterday, Don't You Want Me? LSP 4603 – Coat of Many Colors – Dolly Parton [1971] Coat Of Many Colors/Traveling Man/My Blue Tears/If I Lose My Mind/The Mystery Of The Mystery/She Never Met A Man (She Didn't Like)/Early Morning Breeze/The Way I See You/Here I Am/A Better Place To Live LSP 4604 – First 15 Years – Hank Locklin [1971]Please Help Me/Send Me the Pillow You Dream On/I Don’t Apologize/Release Me/Country Hall of Fame/Before the Next Teardrop Falls/Danny Boy/Flying South/Anna (With Nashville Brass)/Happy Journey LSP 4605 – Charlotte Fever – Kenny Price [1971] Charlotte Fever/You Can't Take It With You/Me And You And A Dog Named Boo/Ruby (Are You Mad At Your Man)/She Cried/Workin' Man Blues/Jody And The Kid/Destination Anywhere/For The Good Times/Super Sideman LSP 4606 – Have You Heard Dottie West – Dottie West [1971] You're The Other Half Of Me/Just One Time/Once You Were Mine/Put Your Hand -

What Kind of Language Is Swahili?*

AAP 47 (1996) 73-95 WHAT KIND OF LANGUAGE IS SWAHILI?* THOMAS J. HINNEBUSCH Introduction Recently we have seen the appearance of an interesting and provocative book on the Swahili. This book, by Ali Amin Mazrui and Ibrahim Noor Shariff (1994), takes a serious look at the question of Swahili identity and origins1 This paper has at least two goals .. One is to help define the nature of the debate about origins, and in so doing I will explicate and critique the Mazrui and Shariff hypothesis .. The second is to reiterate the theme of the study of Swahili by Derek Nurse and the present author (1993), entitled Swahili and Sabaki · A Linguistic History (hereafter N&H).. The linking of Swahili and Sabaki in the title was deliberate: the history of Swahili is inextricably intertwined with that of Sabaki and we cannot speak of the former without direct reference to the latter. The paper is divided into several sections .. The first reviews the position taken by Mazmi and Shariff, the second discusses the view of N&H, implicit in their work on Sabaki, that Swahili is an integrated development from its Afiican heritage, the Sabaki languages. Finally, a critique of the Mazrui and Shariff hypothesis will conclude the paper The Mazrui!Shariff Hypothesis. Mazrui and Shariff (hereafter M&S) present an intriguing proposal for the origin of Swahili. They speculate, based on their reading of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a I st centmy document written by an early Greek traveler to East Afiican tenitories (see Appendix I for the relevant text), that the Swahili language developed fiom a pidgin of Arabic, that is, one whose basic vocabulary was drawn from Arabic . -

Kenyan Fisher Restores Corals in Fished Site for 36 Years by Jennifer O’Leary

theWIOMSA magazine and the environment Issue no. 7 | May 2015 Making a Difference: Restoration of Habitats and Species - Experiences from WIO Region 1 United Travel Agency situated at Gizenga Street-Zanzibar is the most popular and experienced Air Travel Agents. Efficiently managed and well known for its promptness in attending to the needs of its clients and guiding and advising intended travellers of the most economic and convenient connecting flights to almost any part of the world. UTA staff also maintain close, friendly relations with their esteemed clients and ensure satisfactory flight bookings to various destinations. UTA believes in providing excellent air travel services. 3. A Fisher and Conservationist: Kenyan fisher restores corals in fished site for 36 years by Jennifer O’Leary 7. Restoration of Seychelles upland forest biodiversity contents By Christopher Kaiser-Bunbury, James Mougal and Denis Matatiken 13. Community-Based Marine Conservation Initiative in Coastal East Africa Lydia Mwakanema, Edward Kimakwa and Dickson Nyanje 16. Restoration of Mangrove Forests at Limpopo River Estuary, Southern Mozambique By Henriques Balidy and Salomão Bandeira 22. Wasini Community Rallies to Secure Its Future By Lionel Dishon Murage and Jelvas Mwaura 26. Mangrove Restoration: Sharing experiences By Bosire Jared 28. WIO Gallery Last word 32. Towards a Community-managed Future By Lawrence Sisitka 1 Making a difference: Restoration of habitats and species in the region - Experiences from the WIO region editorial The WIOMSA Magazine, The Western Indian Ocean, in common most of these actions are on a People and the Environment with the rest of the world’s oceans, relatively small scale they show the www.wiomsa.org is facing increasing pressure on the ways in which proactive interventions Issue No 7 marine and coastal resources, and can really make a difference. -

Stanley Turrentine Sugar Mp3, Flac, Wma

Stanley Turrentine Sugar mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Sugar Country: US Released: 1971 Style: Soul-Jazz, Post Bop, Modal MP3 version RAR size: 1222 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1634 mb WMA version RAR size: 1534 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 739 Other Formats: WMA DXD ADX VOC DMF AIFF FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Sugar A1 10:00 Written-By – Stanley Turrentine Sunshine Alley A2 11:00 Written-By – Butch Cornell Impressions B 15:30 Written-By – John Coltrane Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Pressed By – Columbia Records Pressing Plant, Terre Haute Published By – Stanshirl Publishing Co. Published By – Daahoud Music Co. Published By – Jowcol Music Credits Bass – Ron Carter Congas – Richard "Pablo" Landrum* Design [Album] – Elton Robinson Drums – Billy Kaye Electric Piano – Lonnie L. Smith, Jr.* Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Guitar – George Benson Liner Notes – Ira Gitler Mastered By – Van Gelder* Organ – Butch Cornell Photography By [Cover Photographs] – Pete Turner Photography By [Liner Photographs] – Chuck Stewart Producer – Creed Taylor Tenor Saxophone – Stanley Turrentine Trumpet – Freddie Hubbard Notes Green CTI labels. Recorded at Van Gelder Studios Recorded November, 1970 Publishing Credits: Track A1: Stanshirl Publ. Co. Track A2: Daahoud Music Co. Track B: Jowcol Music All selections BMI Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: BMI Matrix / Runout (Side A Label): RVG 87658 A Matrix / Runout (Side B Label): RVG 87658 B Matrix / Runout (Side A Etching): RVG•87658•A• Matrix