Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

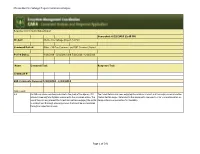

Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Comment Analysis Page 1 Of

Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Comment Analysis Response and Concern Status Report Generated: 6/22/2018 12:48 PM Project: Chetco Fire Salvage Project (53150) Comment Period: Other - 30-Day Comment and ESD Comment Period Period Dates: 4/16/2018 - 5/16/2018 and 5/18/2018 - 6/18/2018 Name Comment Text Response Text Comment # ESD Comments Received 5/18/2018 - 6/18/2018 Vaile, Joseph 1-2 An ESD may prove counterproductive to the goals of the agency, if it The Forest Service has been engaging the public in a robust and thorough process since the prevents meaningful mitigation measures to the proposed action. The Chetco Bar fire began. Refer also to the response to comment 1-1 for more information on use of the ESD may prevent the Forest Service from engaging the public design criteria and evaluation for feasibility. in a robust and thorough planning process that could be accomplished through an objection process. Page 1 of 341 Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Comment Analysis Name Comment Text Response Text 1-5 Please note that the discussion of the agency's desire for an ESD at page The EA states "An additional consideration is the health and safety of forest visitors and 2-6 of the Chetco Bar Fire Salvage EA makes reference to a concern for nearby private landowners due to numerous dead trees, as well as Forest Service staff and "the health and safety of forest visitors." We wholeheartedly agree that forest industry workers working in the Chetco Bar Fire Salvage project area. Traveling or this is a legitimate concern. -

Insider's Guidetoazpolitics

olitics e to AZ P Insider’s Guid Political lists ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE ARIZONA CAPITOL TIMES • Arizona Capitol Reports FEATURING PROFILES of Arizona’s legislative & congressional districts, consultants & public policy advocates Statistical Trends The chicken Or the egg? WE’RE EXPERTS AT GETTING POLICY MAKERS TO SEE YOUR SIDE OF THE ISSUE. R&R Partners has a proven track record of using the combined power of lobbying, public relations and advertising experience to change both minds and policy. The political environment is dynamic and it takes a comprehensive approach to reach the right audience at the right time. With more than 50 years of combined experience, we’ve been helping our clients win, regardless of the political landscape. Find out what we can do for you. Call Jim Norton at 602-263-0086 or visit us at www.rrpartners.com. JIM NORTON JEFF GRAY KELSEY LUNDY STUART LUTHER 101 N. FIRST AVE., STE. 2900 Government & Deputy Director Deputy Director Government & Phoenix, AZ 85003 Public Affairs of Client Services of Client Public Affairs Director Development Associate CONTENTS Politics e to AZ ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE Insider’s Guid Political lists STAFF CONTACTS 04 ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE BEATING THE POLITICAL LEGISLATIVE Administration ODDS CONSULTANTS, DISTRICT Vice President & Publisher: ARIZONA CAPITOL TIMES • Arizona Capitol Reports Ginger L. Lamb Arizonans show PUBLIC POLICY PROFILES Business Manager: FEATURING PROFILES of Arizona’s legislative & congressional districts, consultants & public policy advocates they have ‘the juice’ ADVOCATES, -

Journal of Arizona History Index, M

Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 NOTE: the index includes two citation formats. The format for Volumes 1-5 is: volume (issue): page number(s) The format for Volumes 6 -54 is: volume: page number(s) M McAdams, Cliff, book by, reviewed 26:242 McAdoo, Ellen W. 43:225 McAdoo, W. C. 18:194 McAdoo, William 36:52; 39:225; 43:225 McAhren, Ben 19:353 McAlister, M. J. 26:430 McAllester, David E., book coedited by, reviewed 20:144-46 McAllester, David P., book coedited by, reviewed 45:120 McAllister, James P. 49:4-6 McAllister, R. Burnell 43:51 McAllister, R. S. 43:47 McAllister, S. W. 8:171 n. 2 McAlpine, Tom 10:190 McAndrew, John “Boots”, photo of 36:288 McAnich, Fred, book reviewed by 49:74-75 books reviewed by 43:95-97 1 Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 McArtan, Neill, develops Pastime Park 31:20-22 death of 31:36-37 photo of 31:21 McArthur, Arthur 10:20 McArthur, Charles H. 21:171-72, 178; 33:277 photos 21:177, 180 McArthur, Douglas 38:278 McArthur, Lorraine (daughter), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Lorraine (mother), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Louise, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Perry 43:349 McArthur, Warren, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Warren, Jr. 33:276 article by and about 21:171-88 photos 21:174-75, 177, 180, 187 McAuley, (Mother Superior) Mary Catherine 39:264, 265, 285 McAuley, Skeet, book by, reviewed 31:438 McAuliffe, Helen W. -

Conservation of Greater Sage-Grouse

#714 CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR Conservation of Greater Sage-Grouse A SYNTHESIS OF CURRENT TRENDS AND FUTURE MANAGEMENT J. W. Connelly, S. T. Knick, C. E. Braun, W. L. Baker, E. A. Beever, T. Christiansen, K. E. Doherty, E. O. Garton, S. E. Hanser, D. H. Johnson, M. Leu, R. F. Miller, D. E. Naugle, S. J. Oyler-McCance, D. A. Pyke, K. P. Reese, M. A. Schroeder, S. J. Stiver, B. L. Walker, and M. J. Wisdom Abstract. Recent analyses of Greater Sage-Grouse very low densities in some areas, coupled with (Centrocercus urophasianus) populations indicate large areas of important sagebrush habitat that are substantial declines in many areas but relatively relatively unaffected by the human footprint, sug- stable populations in other portions of the species’ gest that Greater Sage-Grouse populations may be range. Sagebrush (Artemisia spp.) habitats neces- able to persist into the future. We summarize the sary to support sage-grouse are being burned by status of sage-grouse populations and habitats, large wildfires, invaded by nonnative plants, and provide a synthesis of major threats and chal- developed for energy resources (gas, oil, and lenges to conservation of sage-grouse, and suggest wind). Management on public lands, which con- a roadmap to attaining conservation goals. tain 70% of sagebrush habitats, has changed over the last 30 years from large sagebrush control Key Words: Centrocercus urophasianus, Greater projects directed at enhancing livestock grazing to Sage-Grouse, habitats, management, populations, a greater emphasis on projects that often attempt restoration, sagebrush. to improve or restore ecological integrity. Never- theless, the mandate to manage public lands to Conservación del Greater Sage-Grouse: provide traditional consumptive uses as well as Una Síntesis de las Tendencias Actuales y del recreation and wilderness values is not likely to Manejo Futuro change in the near future. -

DEMA Annual Report 2015

ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF EMERGENCY AND MILITARY AFFAIRS 2015 Annual Report Office of the Adjutant General 5636 E. McDowell Rd Phoenix, AZ 85008 Web site: dema.az.gov Social Media: Arizona National Guard AZNationalGuard AZNationalGuard RSS Arizona Division of Emergency Management ArizEIN azein AzEINvideo azeinblog RSS Cover: Soldiers and Airmen from the Arizona National Guard assemble in a mass formation during the Arizona National Guard Muster Dec. 7 at Arizona State University's Sun Devil Stadium in Tempe, Ariz. More than 4,000 Guard Members from throughout the state were present for the historic muster formation. (U.S. Army National Guard Photo by Staff Sgt. Brian A. Barbour) 2 Soldiers and Airmen from the Arizona National Guard assemble in a mass formation during the Arizona National Guard Muster Dec. 7 at Arizona State University's Sun Devil Stadium in Tempe, Ariz. More than 4,000 Guard Members from throughout the state were present for the historic muster formation. (U.S. Army National Guard Photo by Staff Sgt. Brian A. Barbour) INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On September 2, 1865, the Arizona National Guard was established with the first muster of the First Infantry Regiment of Arizona, comprised of five companies of more than 350 enlisted Soldiers and nine officers. From that first muster to serving as the acting Guard of Honor for President Woodrow Wilson during the treaty negotiations ending World War I to the 158th “Bushmasters” being recognized by General Douglas MacArthur as “No greater fighting combat team has ever deployed for battle” to our recent deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq, the Arizona National Guard has established a long and distinguished history of service to Arizona and our nation. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Ore Deposits of the Jerome and Bradshaw Mountains Quadrangles, Arizona

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Hubert Work, Secretary U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY George Otis Smith, Director Bulletin 782 ORE DEPOSITS OF THE JEROME AND BRADSHAW MOUNTAINS QUADRANGLES, ARIZONA BY WALDEMAR LINDGREN WITH STATISTICAL NOTES BY V. C. HEIKES WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1926 CONTENTS Page Introduction - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 History of mining - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -2 Production - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5 Mining districts near area here described - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 General geology - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -7 Physiography - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -7 Paleozoic sediments - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 Pre-Paleozoic peneplain - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 Relation of the plateau province to the mountain region - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 Post-Paleozoic erosion - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 13 Volcanic flows - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Kelly Family Collection

Guide to MS 16 Kelly Family Papers, 1865-1977 1924-1933 1 linear feet, 3 inches Prepared by Hermine Shapiro and Sarah Ashton April 1999 Donations by Alice Jane Kelly Quick, Kelly Family Papers, 1979. Citation: Kelly Family Papers, 1868-1977, MS 16, Library and Archives, Central Arizona Division, Arizona Historical Society. Library and Archives Arizona Historical Society Central Arizona Division Arizona Historical Society at Papago Park, 1300 N. College Avenue, Tempe, AZ 85281 Phone: 480-387-5355, Email: [email protected] 1979.16 MS 16 Kelly Family Papers 2 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES William B. Kelly 1875 Born in Poplar Bluff, Butler County, Missouri 1887 Moved to Tucson, Arizona 1898 Married to Ruth Guernsey on February 7, in Solomonville, Arizona 1901 Purchased the Cochise Review, renamed it the Bisbee Daily Review 1907-1910 Editor and manager of the Arizona Daily Star 1909 Partner with father in State Consolidated Publishing Co. which controlled five state newspapers 1910 Editor and publisher of the Copper Era, Clifton, Arizona 1914-1918 Postmaster, Clifton, Arizona 1923 Controlling interest and manager of Graham County Guardian, Safford, Arizona 1931-39 Senator from Graham County 1936 Delegate to the Democratic National Convention 1939 Appointed Executive Secretary to Governor Robert Taylor Jones 1939-1942 Lived in California 1942 Returned to Safford, Arizona 1943 Sold the Graham County Guardian to the Gila Printing and Publishing Co. 1944 Sold the Copper Era of Clifton to the Gila Printing and Publishing Co. 1948 Died in Tucson, Arizona on February 14 Family: Mrs. Mildred Stevens, San Gabriel, CA; Captain Samuel G. Kelly, U.S.N., Pearl Harbor, TH; Dr. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Listings Arizona

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY SUBMISSION LISTINGS ARIZONA Grace Lutheran Church, Maricopa, Arizona, 93000835 FINDING AID Prepared by National Park Service - Intermountain Region Museum Services Program Tucson, Arizona August 2017 National Register of Historic Places – Multiple Property Submission Listings –Arizona 2 National Register of Historic Places – Multiple Property Submission Listings – Arizona Scope and Content Note: The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. - From the National Register of Historic Places site: http://www.nps.gov/nr/about.htm The Multiple Property Submission (MPS) listings records are unique in that they capture historic properties that are related by theme, general geographic area, and/or period of time. The MPS is the current terminology for submissions of this kind; past iterations include Thematic Resource (TR) and Multiple Resource Area (MRA). Historic properties nominated under the MPS rubric will contain individualized nomination forms and will be linked by a Cover Sheet for the overall group. Historic properties nominated under the TR and MRA rubric are nominated -

AVAILABLE from Arizona State Capitol Museum. Teacher

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 853 SO 029 147 TITLE Arizona State Capitol Museum. Teacher Resource Guide. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 71p. AVAILABLE FROM Arizona State Department of Library, Archives, and Public Records--Museum Division, 1700 W. Washington, Phoenix, AZ 85007. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Secondary Education; Field Trips; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; *Local History; *Museums; Social Studies; *State History IDENTIFIERS *Arizona (Phoenix); State Capitals ABSTRACT Information about Arizona's history, government, and state capitol is organized into two sections. The first section presents atimeline of Arizona history from the prehistoric era to 1992. Brief descriptions of the state's entrance into the Union and the city of Phoenix as theselection for the State Capitol are discussed. Details are given about the actualsite of the State Capitol and the building itself. The second section analyzes the government of Arizona by giving an explanation of the executive branch, a list of Arizona state governors, and descriptions of the functions of its legislative and judicial branches of government. Both sections include illustrations or maps and reproducible student quizzes with answer sheets. Student activity worksheets and a bibliography are provided. Although designed to accompany student field trips to the Arizona State Capitol Museum, the resource guide and activities -

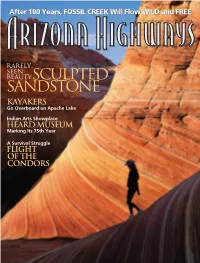

Sculpted Sandstone Kayakers Go Overboard on Apache Lake

After 100 Years, FOSSIL CREEK Will Flow WILD and FREE arizonahighways.com JUNE 2004 rarely seen Beauty Sculpted Sandstone Kayakers Go Overboard on Apache Lake Indian Arts Showplace Heard Museum Marking Its 75th Year A Survival Struggle Flight of the Condors {also inside} JUNE 2004 46 DESTINATION Walnut Canyon The Sinagua Indians had good reason to build their 22 COVER/PORTFOLIO 36 TRAVEL homes along the cliffs of Walnut Canyon. Nature’s Handiwork Chaos in a Tandem Kayak 42 BACK ROAD ADVENTURE in Sandstone Two wigglesome paddlers take a water-camping Drive through the stark beauty of Monument Valley class on Apache Lake and have a boatload of on the Navajo Indian Reservation. The odd shapes of multicolored petrified dunes called trouble getting the hang of capsize recovery. Coyote Buttes grace Arizona’s border with Utah. 48 HIKE OF THE MONTH The route up Strawberry Crater near Flagstaff ENVIRONMENT travels an area once violent Paria Canyon- 6 with volcanic activity. Vermilion Cliffs Fossil Creek Going Wild Again Wilderness By the end of December, this scenic stream in Coyote Monument 2 LETTERS & E-MAIL Buttes Valley central-Arizona will revert to a natural state as two Grand Canyon electric power plants are closed after nearly a 3 TAKING THE National Park OFF-RAMP Strawberry Crater hundred years of operation. Walnut Canyon National Monument 40 HUMOR Fossil MUSEUMS Creek 16 PHOENIX Heard Museum Marks 41 ALONG THE WAY Apache A nostalgic drive across Maricopa Lake Wells 75th Anniversary America is hard to beat— TUCSON Phoenix’s noted institution for Indian arts and culture except by arriving home continues to tie native creativity and traditions to in Arizona. -

Journal of Arizona History Index, F

Index to the Journal of Arizona History, F Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 NOTE: the index includes two citation formats. The format for Volumes 1-5 is: volume (issue): page number(s) The format for Volumes 6 -54 is: volume: page number(s) F Faber, Jerdie (Indian school teacher) 6:131 Fabila, Alfonso, cited 8:131 “The Fabulous Sierra Bonita,” by Earle R. Forrest 6:132-146 “The Face of Early Phoenix,” compiled by A. Tracy Row 13:109-122 Faces of the Borderlands, reviewed 18:234-35 Facts About the Papago Indian Reservation and the Papago People, reviewed 13:295-97 Fagan, Mike, of Harshaw 6:33 Fagen, Ken, photo of 50:218 Fagerberg, Dixon, Jr., book by, reviewed 24:207-8 Fagerberg, John E. 39:163 Fages, Pedro 13:124, 126-29; 44:50, 51, 71 n. 28 biography of 9:223-44 cited 7:62 diary of 9:225-44 diary of, listed 27:145 1 Index to the Journal of Arizona History, F Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 Fahlen, F. T. 14:55-56 Fahlman, Betsy, book by, reviewed 44:95-96; 51:381-83 book reviewed by 42:239-41; 47:316-17; 51:185-86 books reviewed by 49:293-94 Fain, Granville (Dan) 19:261-62, 264, 271 Fain, Norman W. 19:264, 266; 43:364, 366 Fair, Captain (at Santa Cruz in 1849) 28:108 Fair, James G. 34:139-40 Fair Laughs the Morn, by Genevieve Gray, reviewed 36:105 Fair Price Commission 46:158 Fair, (senator of Nevada) IV(1)37 Fair Truckle (horse) 47:17 Fairbank, Arizona 7:9; 8:164, 166, 168; 37:7, 24 n.