Songs of Ossian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry Director: Nathan T. Elkins, Ph.D The Mausoleum of Constantina and Helena in Rome once held two sarcophagi, but the second has never been properly identified. Using the decoration in the mausoleum and recent archaeological studies, this thesis identifies the probable design of the second sarcophagus. This reconstruction is confirmed by a fragment in the Istanbul Museum, which belonged to the lost sarcophagus. This is contrary to the current misattribution of the fragment to the sarcophagus of Constantine. This is only the third positively identified imperial sarcophagus recovered in Constantinople. This identification corrects misconceptions about both the design of the mausoleum and the history of the fragment itself. Using this identification, this thesis will also posit that an altar was originally placed in the mausoleum, a discovery central in correcting misconceptions about the 4th century imperial liturgy. Finally, it will posit that the decorative scheme of the mausoleum was not random, but was carefully thought out in connection to the imperial funerary liturgy itself. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS _____________________________________________ Dr. Nathan T. Elkins, Art Department APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM ____________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director DATE: _____________________ SARCOPHAGI IN CONTEXT: IDENTIFYING THE MISSING SARCOPHAGUS OF HELENA IN THE MAUSOLEUM OF -

EARLY CHRISTIAN and BYZANTINE ART

Humanities 1B, Honors, Fall, 2015 Rostankowski EARLY CHRISTIAN and BYZANTINE ART Trajan 98-117 Antoninus Pius 138-161 Constantine 307-337 Hadrian 117-138 Marcus Aurelius 161-180 Justinian 527-565 Catacombs: Christian burial places, underground; hollowed out of the soft stone called tufa into rooms, with many small niches for burial. Loculus: catacomb burial niche Cubiculum: catacomb room or gallery. CONSTANTINE • Colossal seated sculpture (remaining head, appendages) • Arch of Constantine – used sculptural components from monuments of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius SCULPTURE • Good Shepherd – free standing • Christ enthroned, mid-4th century • Mithraic representations: Birth of Mithras, Life of Mithras from his altar, ascension of Mithras/Elijah’s ascent Sarcophagi: Mixed Styles • Sarcophagus with Angels (a la Nikes), 3rd century • Jonah Sarcophagus, early 4th century • Toils of Hercules sarcophagus, 4th century • Two Brothers sarcophagus, O.T. & N.T., 4th century • Madonna and the Magi Sarcophagus, early 5th century IVORY DIPTYCHS: Classical to non-classical • Nicomachi a& Symmachi – Bacchus priestess, Ceres priestess, late 4th century • Emperor Anastasius ca. 517 PAINTING - Catacombs • Catacombs of Saints Peter and Marcellinus, late 3rd century – 4th century • Jonah, Noah, Baptism of Christ, Raising of Lazarus, Adam & Eve • Mausoleum of the Julii, late 3rd century - Christ as Sol Invictus, mosaic. Iconoclasm • Christ, St. Catherine’s monastery, Mt. Sinai, Egypt, ca. 6th century • Virgin with Sts. Theodore and George, 6th century ARCHITECTURE Rome • Old St. Peter’s ca. 330 Basilica – a rectilinear building used by Roman government as a bureaucratic facility. Clerestory – raised roof above central aisle of a structure, usually with many windows, to allow light and air into a building. -

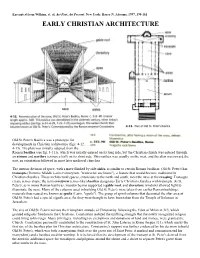

Early Christian Architecture

Excerpted from Wilkins, et. al, Art Past, Art Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997, 190-161 EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE Old St. Peter's Basilica was a prototype for developments in Christian architecture (figs. 4-12, 4-13). The plan was initially adapted from the Roman basilica (see fig. 3-111), which was usually entered on its long side, but the Christian church was entered through an atrium and narthex (entrance hall) on its short side. This narthex was usually on the west, and the altar was toward the east, an orientation followed in most later medieval churches. The interior division of space, with a nave flanked by side aisles, is similar to certain Roman basilicas. Old St. Peter's has transepts (from the Middle Latin transseptum, "transverse enclosure"), a feature that would become traditional in Christian churches. These architectural spaces, extensions to the north and south, meet the nave at the crossing. Transepts create across shape; the term cruciform (cross-like) basilica designates Early Christian churches with transepts. At St. Peter's, as in many Roman basilicas, wooden beams supported a gable roof, and clerestory windows allowed light to illuminate the nave. Many of the columns used in building Old St. Peter's were taken from earlier Roman buildings; materials thus reused are known as spolia (Latin, "spoils"). The group of spiral columns that decorated the altar area at Old St. Peter's had a special significance, for they were thought to have been taken from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The size of Old St. Peter's mirrors the triumphant attitude of Christianity following the Edict of Milan in 313, which granted religious freedom to the Christians. -

The Roman Empire Mr

The roman empire Mr. Cline History Marshall High School Marshall High School Mr. Cline Western Civilization I: Ancient Foundations Unit Four ED * The Legacy of the Roman Empire • Perhaps nothing has defined western civilization as much as having once been part of the Roman Empire • The construction of cities, buildings, monuments, and the roads that connected them throughout the empire brought a feeling of connectedness to people living thousands of miles apart. • Many great cities of Europe today began as Roman military camps, or trade centers • London • Vienna • Zurich • Paris • Orleans • Palermo • Cologne • Florence • Barcelona • Milan • York • Strasbourg • Budapest • Geneva English Spelling of Greek Word Translation Letter Iota Iesous Jesus Chi Christos Christ Theta Theou God's Ypsilon Uios Son Sigma Soter Savior * The Legacy of the Roman Empire • The inventions and innovations which were generated in the Roman Empire profoundly altered the lives of the ancient people and continue to be used in cultures around the world today. • indoor plumbing, • aqueducts, • and even fast-drying cement were either invented or improved upon by the Romans. • The calendar used in the West derives from the one created by Julius Caesar, and the names of the days of the week (in the romance languages) and months of the year also come from Rome. • Apartment complexes (known as `insula), public toilets, locks and keys, newspapers, even socks all were developed by the Romans as were shoes, a postal system (modeled after the Persians), cosmetics, the magnifying glass, and the concept of satire in literature. • During the time of the empire, significant developments were also advanced in the fields of medicine, law, religion, government, and warfare. -

The Traditio Legis: Anatomy of an Image

The Traditio Legis: Anatomy of an Image Robert Couzin Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 081 5 ISBN 978 1 78491 082 2 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and R Couzin 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Hollywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ ii Preface ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� v Part I� An introduction to the image Chapter 1: The invention of the traditio legis ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 2 1.1 Nomenclature ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Definition ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 2: The corpus -

Expanding the Christian Footprint: Church Building in the City and the Suburbium Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2017 Expanding the Christian Footprint: Church Building in the City and the Suburbium Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. 2017. "Expanding the Christian Footprint: Church Building in the City and the Suburbium." In I. Foletti and M. Gianandrea (eds.), The iF fth eC ntury in Rome: Art, Liturgy, Patronage, Rome, Viella: 65-97. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/105 For more information, please contact [email protected]. I libri di Viella Arte Studia Artium Mediaevalium Brunensia, 4 Editorial board: Klára Benešovská, Ivan Foletti (dir.), Herbert Kessler, Serena Romano, Elisabetta Scirocco Ivan Foletti Manuela Gianandrea The Fifth Century in Rome: Art, Liturgy, Patronage With articles by Sible de Blaauw, Olof Brandt, Zuzana Frantová and Dale Kinney viella Copyright © 2017 – Viella s.r.l. All rights reserved First published 2017 ISBN 978-88-6728-211-1 Published with the support of the Department of Art History, Masaryk University, Brno Edited by Adrien Palladino viella libreria editrice via delle Alpi 32 I-00198 ROMA tel. 06 84 17 75 8 fax 06 85 35 39 60 www.viella.it Table of contents Introduction 7 I. New Languages Old Patterns Ivan Foletti God From God. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

“HE IS THE IMAGE AND GLORY OF GOD”: POLEMICAL IMAGES OF CHRIST FROM THE TIME OF CONSTANTINE By MARY WRIGHT A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Mary Wright To my husband, Matthew, whose faith in me never faltered ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my parents, first and foremost, for instilling in me the interest of Christianity and its origins. I also wish to thank my husband who stood by me when life grew difficult, yet still he believed in me and pushed me to complete this work. Last, but not least, I wish to thank Dr. Ashley Jones and Dr. Mary Ann Eaverly, my mentors, for their patience and guidance. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 6 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 10 Overview ................................................................................................................. 18 2 ROLES THAT WERE ADAPTED BY CHRIST ....................................................... -

Meditative Qualities of the Pictorial Narratives in the Mural

i MEDITATIVE QUALITIES OF THE PICTORIAL NARRATIVES IN THE MURAL PAINTINGS OF ALBERTUS PICTOR: A STUDY OF THE JONAH AND THE WHALE PREFIGURATION AND CHRIST’S CRUCIFIXION By Meghan Lee Baker Livers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ii ©COPYRIGHT by Meghan Lee Baker Livers 2016 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First I would like to express thanks to my committee for the support and encouragement they provided: Dr. Regina Gee, my committee chair, Dr. Todd Larkin, Dr. Melissa Ragain, and Dr. Susanne Cowan. I offer my appreciating for the learning opportunities made available to me by my committee. Also, thank you to Dr. Pia Melin and Dr. Christina Sandquist-Öberg for taking time out of their busy schedules to visit with me and discuss Albertus Pictor while I was in Sweden. The completion of this project could not have been accomplished without the financial support from Montana State University’s Graduate School and MSU’s School of Art and Architecture. I am also grateful for the assistance offered to me by the Svenska Kyrkan and taking the time to open some of the churches during my visit. Thank you to my friend Maria Forslind and her family for acting as translators and guides while I was researching in Sweden. Additionally, thank you to my colleagues, Michele Corriel, Jesine Munson, and Kate Cottingham for offering advice and support through the process of writing. Finally, thank you to my supportive husband, who spent long hours helping me edit and supporting me through the research, the writing, and the defense. -

Early Christian and Byzantine

Joslyn Art Museum SURVEY OF WESTERN ART HISTORY I Early Christian and Byzantine Art ambulatory mystery cult syncretism niche / blind niche orant / orant figure lunette catacombs gallery typology / typological prefiguration choir schism minaret martyrium pendentive altar squinch crucifix screen walls apse transubstantiation codex triumphal arch folios triumphal cross icon gabled roof iconic transept iconoclast cruciform iconophile tesserae sign / symbol mosaic Greek cross relic deesis Arch of Constantine, Rome 313 AD Marble 1 Dura Europos synagogue in Syria c. 245 Tempera on plaster Moses Giving Water to the Tweleve Tribes of Israel Dura Europos synagogue c. 245 2 Christ as the Good Shepherd Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome Early Christian, 2nd-3rd century Fresco 3 4 Early Christian sarcophagus Santa maria Antiqua, Rome 4th century marble Reconstruction diagram and plan of Old Saint Peter’s basilica, Rome 333-390 5 Roman Forum Christus-Sol, from the Christian Mausoleum of the Julii under Saint Peter’s Mid 3rd century Vault mosaic St. Paul outside the Walls, Rome Begun 385 Restored after a fire in 1823 6 Interior of the martyrium of Santa Costanza, Rome Early Christian, c. 350 Ambulatory ceiling of Santa Costanza, Rome Early Christian, c. 350 Mosaic Galla Placidia, Ravenna, c. 425-426 7 Interior of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia showing niche with two apostles and the Saint Lawrence mosaic, Ravenna c. 425-426 Christ as the Good Shepherd, the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna c. 425-426 Mosaic Geometric border from the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna c. 425-426 mosaic 8 Exterior of San Vitale, Ravenna 540-547 Plan of San Vitale, Ravenna 540-547 Interior of San Vitale looking east toward the apse, Ravenna 540-547 9 Choir ceiling, San Vitale, Ravenna c. -

Santa Costanza Via Nomentana, 349 from Termini Station Take Bus 36 Pampanini 10 Stops to Nomentana/St

Santa Costanza Via Nomentana, 349 From Termini Station take Bus 36 Pampanini 10 stops to Nomentana/St. Agnese. 9 AM – 12PM (Mon – Sat) 4 PM – 6 PM (Tue - Sun) The Mausoleum of Santa Costanza is named for Constantine the Great's daughter Constantia (also known as Constantina or Costanza), but the latest scholarship suggests it was actually built for her sister Helena, who died in 360. Early accounts record that Constantine built a funerary hall here on the imperial estate at the request of Constantia - this is the long building now in ruins next to the mausoleum. The funerary hall was dedicated to the virgin martyr St. Agnes and resembled others built by Constantine in this period. The early accounts also report that Constantine built a baptistery on the site, in which both Constantia and Constantine's sister were baptized by Pope Sylvester (315). It was long assumed that the existing mausoleum is this baptistery, but excavations beneath its north end in 1992 revealed a triconch (clover-shaped) building that is a more likely candidate. After Constantia died in 354, her body was brought back from Bithynia to be buried on the imperial estate in Rome. It was long thought she was buried in the mausoleum, but new data indicates the building was probably still unfinished at that time. So she was probably buried either in the baptistery or in the apse of the funerary hall. The round mausoleum that survives today was probably built in the 360s, based on the combination of pagan and Christian elements in the mosaics. -

Santa Costanza Testo

ROMA - MAUSOLEUM OF SANTA COSTA N Z A BASILICA OF SANT’AGNESE The Basilica of Sant’Agnese was built between 337 and 351 at the will of the eldest daughter of Constantino, Constantina Augusta, in the ve ry years in which the empress lived in Rome, between the death of her first husband Annibaliano, King of Pontus, and the subsequent marriage with Constantino Gallo, Caesar of the East, which led her to settle in Antioch. On the land of Via Nomentana, where there was the tomb of the virg i n - m a r tyr Sant’Agnese - dead just when she was thirt e e n years old, a basilica in her honour was built at the will of Costantina, that was a fervent devotee of the saint. So it was erect- ed the largest ambu l a t o r y basilica, with the nave and two side aisles (98 meters long and 40 metres wide), of which unfor- t u n a t e ly only a few ruins remain today: they consist of the outer wall of the west side, whose apse was supported by high s u b s t ructures, necessary because of the slope of the land. The ex c avations have revealed the presence of the remains of some Christian martyrs under the floor of the basilica. Compared to the previous ambu l a t o ry basilicas, the plan of the Basilica of Sant’Agnese was considerably more detailed and more evo l ved: it was made of alternating bricks and tufa and, thanks to the rectangular windows, a widespread and strong lighting was provided inside the church. -

Palladio's Rome

Palladio’s Rome Vaughan Hart and Peter Hicks “Being aware of the great desire in everyone to acquire a thorough understanding of the antiquities in, and other worthy features of, so celebrated a city, I came up with the idea of compiling the present book, as succinctly as I could, from many completely reliable authors, both ancient and modern, who had written at length on the subject.” —Andrea Palladio, L’antichità (1554), fol.1. Abstract Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) published in 1554 two enormously popular guides to the churches and antiquities of Rome. This paper will examine the significance of these two works to Palladio’s understanding of ancient architecture, and to the meaning of his own work as an architect. The origins of the Rome guidebook tradition will be outlined, and Palladio’s attempt to modernise the standard medieval guides in the light of the contemporary pilgrim’s requirement for a more logical itinerary to the ‘eternal city.’ The paper will attempt to show that Palladio’s neglected guides are nothing less than central to our full appreciation of one of the most celebrated architects of all time. Introduction Our recent book, entitled Palladio’s Rome, brings together for the first time in translated form the publications on Rome of one of the most famous figures of the Italian Renaissance, whose influence was both immediate and long lasting.1 The architecture of Andrea Palladio (1508– 1580) is so well known that it seems surprising that his works on the monuments of ancient and medieval Rome should be relatively unfamiliar, and therefore be downplayed as sources for our understanding of his concerns.