University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-Pgi-Apuleius6634 Finl

Index This online index is a much fuller version than the index that was abbre - viated for print. Like the print index, the online index has a number of goals beyond the location of proper names. For some names and technical terms it serves as a glossary and provides notes; for geograph - ical items it provides references to specific maps. But it is primarily de - signed to facilitate browsing. Certain key terms (sadism/sadistic, salvation/salvific/savior, sticking one’s nose in) can be appreciated for the frequency of their occurrence and have not been subdivided. Certain plot realities have been highlighted (dogs, food, hand gestures, kisses, processions, roses, shackles and chains, slaves, swords); certain themes and motifs have been underlined (adultery, disguise, drama, escape, gold, hair, hearth and home, madness, suicide); some quirks of the translation have been isolated (anachronisms, Misericordia! ); minu - tiae of animals, plants, language have been cataloged (deer, dill, and der - ring-do). The lengthy entry on Lucius tries to make clear the multiplicities of his experience. By isolating the passages in which he ad - dresses himself, or speaks of “when he was Lucius,” I hope to make the difficult task of determining whether the man from Madauros is really the same as Lucius the narrator, or the same as Apuleius the author, a little bit easier. abduction, 3.28–29, 4.23–24, 4.26; Actium (port in Epirus; site of Augus - dream of, 4.27 tus’ naval victory over Antony and Abstinence (Sobrietas, a goddess), 5.30; Cleopatra; Map -

Gods, Planets, Astrology

Roman and Greek Mythology Names: Gods, Planets, Astrology By J. Aptaker Roman & Greek Mythology Names: Gods, Planets This page will give the Roman and Greek mythology names of gods after whom planets were named, and will explain how those planets came to be named after them. It will also give pictures of these gods, and tell their stories. By extension, these gods’ planets, in the minds of the ancients, influenced the personality traits of people born at various times of the year. Thus, the connection between gods, planets, and astrology. In the Beginning Was Chaos The ancients perceived that although most stars maintained a relatively fixed position, some of them seemed to move. Five such “wandering stars”--the word “planet” comes from a Greek word meaning “to wander or stray”--were obvious to the naked eye. These were Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. In fact, it is thought that both the seven- day week and the overall sacredness of the number seven within many mystical/religious traditions may have begun with the observation of seven heavenly bodies which moved: the five visible planets, the sun, and the moon. Each of these seven heavenly bodies is associated with a particular day of the week. According to Greek mythology, the first god was Chaos. While the word Chaos brings certain images of mayhem and disorderliness to the English-speaking mind, the Greek god Chaos was just a big, empty, black, Nothing. Chaos was Nothingness, the Void, or empty space. After Chaos came the goddess Earth, who was known to the Greeks as Ge (or Gaia), and to the Romans as Terra. -

Sevy 1 Monique Sevy Professor Julianne Sandlin AH 205 11035 8 March 2012 the Augustus of Primaporta: a Message of Imperial Divin

Sevy 1 Monique Sevy Professor Julianne Sandlin AH 205 11035 8 March 2012 The Augustus of Primaporta: A Message of Imperial Divinity The Augustus of Primaporta is a freestanding marble sculpture in the round. The sculpture is a larger than life 6’ 8” tall and is an example of early Roman imperial portrait sculpture. This sculpture is currently displayed in the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museums in Rome, Italy. This marble portrait of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, is a very naturalistic statue. Although the sculpture was carved in the early first century, at the time of the Roman empire, Augustus stands in a Classical Greek contrapposto pose. While the sculptor of this piece is unknown, we do know that he or she followed the canon of the High Classical Greek sculptor named Polykleitos in pose, idealization, and proportion (Stokstad, Cothren 174). The Augustus of Primaporta statue sends not only a message of the Emperor Augustus as an accomplished military leader, but also clearly suggests that the emperor is a divine being. The Augustus of Primaporta is a three-dimensional sculpture. The statue actually occupies space; therefore there is no need to use illusion to create suggested space. However, the statue does use space, both negative and positive, to influence the viewer. The negative space between Augustus’s calves forms an implied triangle, or arrow, directing the viewer’s gaze upward toward the center focal point of the piece, while the positive space of the emperor’s raised and pointed right arm forcefully pierces the space surrounding the piece. -

2017-2018 Annual Investment Report Retirement System Investment Commission Table of Contents Chair Report

South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission 2017-2018 Annual Investment Report South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission Annual Investment Report Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018 Capitol Center 1201 Main Street, Suite 1510 Columbia, SC 29201 Rebecca Gunnlaugsson, Ph.D. Chair for the period July 1, 2016 - June 30, 2018 Ronald Wilder, Ph.D. Chair for the period July 1, 2018 - Present 2017-2018 ANNUAL INVESTMENT REPORT RETIREMENT SYSTEM INVESTMENT COMMISSION TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAIR REPORT Chair Report ............................................................................................................................... 1 Consultant Letter ........................................................................................................................ 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................... 7 Commission ............................................................................................................................... 9 Policy Allocation ........................................................................................................................13 Manager Returns (Net of Fees) ..................................................................................................14 Securities Lending .....................................................................................................................18 Expenses ...................................................................................................................................19 -

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry Director: Nathan T. Elkins, Ph.D The Mausoleum of Constantina and Helena in Rome once held two sarcophagi, but the second has never been properly identified. Using the decoration in the mausoleum and recent archaeological studies, this thesis identifies the probable design of the second sarcophagus. This reconstruction is confirmed by a fragment in the Istanbul Museum, which belonged to the lost sarcophagus. This is contrary to the current misattribution of the fragment to the sarcophagus of Constantine. This is only the third positively identified imperial sarcophagus recovered in Constantinople. This identification corrects misconceptions about both the design of the mausoleum and the history of the fragment itself. Using this identification, this thesis will also posit that an altar was originally placed in the mausoleum, a discovery central in correcting misconceptions about the 4th century imperial liturgy. Finally, it will posit that the decorative scheme of the mausoleum was not random, but was carefully thought out in connection to the imperial funerary liturgy itself. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS _____________________________________________ Dr. Nathan T. Elkins, Art Department APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM ____________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director DATE: _____________________ SARCOPHAGI IN CONTEXT: IDENTIFYING THE MISSING SARCOPHAGUS OF HELENA IN THE MAUSOLEUM OF -

Early Mythology Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY EARLY MYTHOLOGY ANCESTRY 1 INTRODUCTION This book covers the earliest history of man and the mythology in some countries. The beginning from Adam and Eve and their descendants is from the Old Testament, but also by several authors and genealogy programs. The age of the persons in the lineages in Genesis is expressed in their “years”, which has little to do with the reality of our 365-day years. I have chosen one such program as a starting point for this book. Several others have been used, and as can be expected, there are a lot of conflicting information, from which I have had to choose as best I can. It is fairly well laid out so the specific information is suitable for print. In addition, the lineage information shown covers the biblical information, fairly close to the Genesis, and it also leads to both to mythical and historical persons in several countries. Where myth turns into history is up to the reader’s imagination. This book lists individuals from Adam and Eve to King Alfred the Great of England. Between these are some mythical figures on which the Greek (similar to Roman) mythology is based beginning with Zeus and the Nordic (Anglo-Saxon) mythology beginning with Odin (Woden). These persons, in their national mythologies, have different ancestors than the biblical ones. More about the Nordic mythology is covered in the “Swedish Royal Ancestry, Book 1”. Of additional interest is the similarity of the initial creation between the Greek and the Finnish mythology in its national Kalevala epos, from which a couple of samples are included here. -

Which Deity Is Calling You?

Which Deity is CAlling You? How to Use Palmistry to Find Your Patron God and Goddess Summer of Magic 2018 | Rachel Erazo How to Use Palmistry to Find Your Patron Deity When I first started energy work, let alone talking to spirits… I didn’t know what the hell I was. I came from a religiously-strict background where everything was decided for me, from the clothes I wore to how I spent my Monday, Thursday, Saturday, and Sunday. When I broke away from “the truth”, I was anti- established religion. I was happy with being spiritual – I knew there was something out there! – but I didn’t make an effort to find out. I didn't like believing I needed a name for myself I didn't want to believe in a higher power or being; they never saved me when I called for them I was afraid of creating a regular practice of anything, just in case it turned into a strict dogma At the same time, I missed having a label. It was important to me, especially with an overbearing family, to have something to call what I believe. SUMMER OF MAGIC 2018 | RACHEL ERAZO How to Use Palmistry to Find Your Patron Deity As I started working on my energy and changing my life, I realized I needed a steady foundation for what I was. I could be as eclectic as I wanted to be AND have a name. Once I sat down to figure out my personal beliefs by reading mythology, studying history, and experiencing different streams of thought through literature I realized something incredibly valuable: In order to be a successful, powerful psychic you need a basis of belief. -

Roman Images of Diana Bettina Bergmann Mount Holyoke College

! "! A Double Triple Play: Roman Images of Diana Bettina Bergmann Mount Holyoke College John Miller’s study of Augustan Apollo inspired me to return to Paul Zanker’s The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (1988), a book that demonstrated the immense potential of an interdisciplinary approach rather than exclusive focus on any one artistic mode. Nearly a quarter of a century later, this session continues to grapple with the challenges of interdisciplinarity and assessment of the Augustan era. Miller’s subtle analysis of poets’ intricate language invites a renewed consideration of the relationships among texts, sites, and images. The operations that he describes -- conflating, juxtaposing, allusion, correspondence, association – can be related directly to the analysis of topography and monuments as well. I also would like to extend his recommendation to “analyze variations in light of one another” and consider visual images of an elusive figure in his book, the divine twin Diana. The goddess appears, often as an afterthought, literally placed in parentheses after a mention of Apollo, until she assumes prominence in Miller’s insightful treatment of the saecular games (Chapter Five). As I will argue, however, in the visual environment of Augustan Rome, she would have been impossible to bracket out. While the goddess, fiercely independent, often appeared alone, in the second half of the first century B.C.E. she became a faithful companion of Apollo. Diva triformis The late republic and early empire saw an explosion of images of the divine sister, who, like Apollo, evolved into a dynamic, shape-shifting deity, slipping from one identity to another: Hecate, Trivia, Luna, Selene, even Juno Lucina. -

EARLY CHRISTIAN and BYZANTINE ART

Humanities 1B, Honors, Fall, 2015 Rostankowski EARLY CHRISTIAN and BYZANTINE ART Trajan 98-117 Antoninus Pius 138-161 Constantine 307-337 Hadrian 117-138 Marcus Aurelius 161-180 Justinian 527-565 Catacombs: Christian burial places, underground; hollowed out of the soft stone called tufa into rooms, with many small niches for burial. Loculus: catacomb burial niche Cubiculum: catacomb room or gallery. CONSTANTINE • Colossal seated sculpture (remaining head, appendages) • Arch of Constantine – used sculptural components from monuments of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius SCULPTURE • Good Shepherd – free standing • Christ enthroned, mid-4th century • Mithraic representations: Birth of Mithras, Life of Mithras from his altar, ascension of Mithras/Elijah’s ascent Sarcophagi: Mixed Styles • Sarcophagus with Angels (a la Nikes), 3rd century • Jonah Sarcophagus, early 4th century • Toils of Hercules sarcophagus, 4th century • Two Brothers sarcophagus, O.T. & N.T., 4th century • Madonna and the Magi Sarcophagus, early 5th century IVORY DIPTYCHS: Classical to non-classical • Nicomachi a& Symmachi – Bacchus priestess, Ceres priestess, late 4th century • Emperor Anastasius ca. 517 PAINTING - Catacombs • Catacombs of Saints Peter and Marcellinus, late 3rd century – 4th century • Jonah, Noah, Baptism of Christ, Raising of Lazarus, Adam & Eve • Mausoleum of the Julii, late 3rd century - Christ as Sol Invictus, mosaic. Iconoclasm • Christ, St. Catherine’s monastery, Mt. Sinai, Egypt, ca. 6th century • Virgin with Sts. Theodore and George, 6th century ARCHITECTURE Rome • Old St. Peter’s ca. 330 Basilica – a rectilinear building used by Roman government as a bureaucratic facility. Clerestory – raised roof above central aisle of a structure, usually with many windows, to allow light and air into a building. -

Roman Empire

Rome! Early Days • Rome (750 BCE) – Founded by Latins – Tiber River – Influences from other Mediterranean cultures • Etruscans • Greeks • Phoenicians Origin Myths • Adopt Greek Gods – Active Greek Roman • Aeneas Aphrodite............... Venus – Virgil’s Aeneid Apollo.....................Apollo • Romulus and Remus Ares........................ Mars Athena....................Minerva – Numitor deposed by Amulius Hades..................... Pluto Hera........................Juno – Rhea Silvia impregnated by Mars Hermes...................Mercury – Boys raised by wolves Poseidon.................Neptune – Revenge Zeus........................Jupiter – Rome Women in Rome • “Rape of the Sabines” • Influence in the home • Tombstone – “She was chaste, she was thrifty, she remained at home, she spun wool.” Women in Rome • “Rape of the Sabines” • Influence in the home • Marriage • Tombstone – “She was chaste, she was thrifty, she remained at home, she spun wool.” • Juvenal – Against Women (pg. 151) • Uses criticism of women to make a larger point about the state of Imperial Rome Republic 509-133 BCE • Government – Assembly of the Tribes – Roman Senate • Elected positions – Consuls – Quaestors and Praetors – Censors – Dictator Struggle of the Orders • Class division – Power struggle between plebeians and patricians – Civic and civil rights • 445 BCE - Intermarriage • 367 BCE – First plebeian elected consul • 300 BCE – can enter all levels of priesthood • 287 BCE – Laws of Popular Assembly applied to everyone This looks familiar • Conquer the people • Assert -

Total of 10 Paces Only May Be Xerox •

CENTRE FOR ~EWFOUNOI AND SiUDJES TOTAL OF 10 PACES ONLY MAY BE XEROX •. O (Without Author's ~rml~\lon) Reconsidering Ovid's Ides of March: A Commentary on Fasti 3.697-710 By © Julia M. E. Sinclair A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Classics Faculty of Arts Memorial University ofNewfoundland June 2004 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Bibliotheque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de !'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 0-494-02376-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 0-494-02376-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a Ia Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I' Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve Ia propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits meraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. -

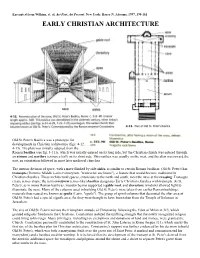

Early Christian Architecture

Excerpted from Wilkins, et. al, Art Past, Art Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997, 190-161 EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE Old St. Peter's Basilica was a prototype for developments in Christian architecture (figs. 4-12, 4-13). The plan was initially adapted from the Roman basilica (see fig. 3-111), which was usually entered on its long side, but the Christian church was entered through an atrium and narthex (entrance hall) on its short side. This narthex was usually on the west, and the altar was toward the east, an orientation followed in most later medieval churches. The interior division of space, with a nave flanked by side aisles, is similar to certain Roman basilicas. Old St. Peter's has transepts (from the Middle Latin transseptum, "transverse enclosure"), a feature that would become traditional in Christian churches. These architectural spaces, extensions to the north and south, meet the nave at the crossing. Transepts create across shape; the term cruciform (cross-like) basilica designates Early Christian churches with transepts. At St. Peter's, as in many Roman basilicas, wooden beams supported a gable roof, and clerestory windows allowed light to illuminate the nave. Many of the columns used in building Old St. Peter's were taken from earlier Roman buildings; materials thus reused are known as spolia (Latin, "spoils"). The group of spiral columns that decorated the altar area at Old St. Peter's had a special significance, for they were thought to have been taken from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The size of Old St. Peter's mirrors the triumphant attitude of Christianity following the Edict of Milan in 313, which granted religious freedom to the Christians.