PR Church Decorative Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rome: a Pilgrim’S Guide to the Eternal City James L

Rome: A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Eternal City James L. Papandrea, Ph.D. Checklist of Things to See at the Sites Capitoline Museums Building 1 Pieces of the Colossal Statue of Constantine Statue of Mars Bronze She-wolf with Twins Romulus and Remus Bernini’s Head of Medusa Statue of the Emperor Commodus dressed as Hercules Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Statue Statue of Hercules Foundation of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus In the Tunnel Grave Markers, Some with Christian Symbols Tabularium Balconies with View of the Forum Building 2 Hall of the Philosophers Hall of the Emperors National Museum @ Baths of Diocletian (Therme) Early Roman Empire Wall Paintings Roman Mosaic Floors Statue of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus (main floor atrium) Ancient Coins and Jewelry (in the basement) Vatican Museums Christian Sarcophagi (Early Christian Room) Painting of the Battle at the Milvian Bridge (Constantine Room) Painting of Pope Leo meeting Attila the Hun (Raphael Rooms) Raphael’s School of Athens (Raphael Rooms) The painting Fire in the Borgo, showing old St. Peter’s (Fire Room) Sistine Chapel San Clemente In the Current Church Seams in the schola cantorum Where it was Cut to Fit the Smaller Basilica The Bishop’s Chair is Made from the Tomb Marker of a Martyr Apse Mosaic with “Tree of Life” Cross In the Scavi Fourth Century Basilica with Ninth/Tenth Century Frescos Mithraeum Alleyway between Warehouse and Public Building/Roman House Santa Croce in Gerusalemme Find the Original Fourth Century Columns (look for the seams in the bases) Altar Tomb: St. Caesarius of Arles, Presider at the Council of Orange, 529 Titulus Crucis Brick, Found in 1492 In the St. -

Liturgy, Space, and Community in the Basilica Julii (Santa Maria in Trastevere)

DALE KINNEY Liturgy, Space, and Community in the Basilica Julii (Santa Maria in Trastevere) Abstract The Basilica Julii (also known as titulus Callisti and later as Santa Maria in Trastevere) provides a case study of the physical and social conditions in which early Christian liturgies ‘rewired’ their participants. This paper demon- strates that liturgical transformation was a two-way process, in which liturgy was the object as well as the agent of change. Three essential factors – the liturgy of the Eucharist, the space of the early Christian basilica, and the local Christian community – are described as they existed in Rome from the fourth through the ninth centuries. The essay then takes up the specific case of the Basilica Julii, showing how these three factors interacted in the con- crete conditions of a particular titular church. The basilica’s early Christian liturgical layout endured until the ninth century, when it was reconfigured by Pope Gregory IV (827-844) to bring the liturgical sub-spaces up-to- date. In Pope Gregory’s remodeling the original non-hierarchical layout was replaced by one in which celebrants were elevated above the congregation, women were segregated from men, and higher-ranking lay people were accorded places of honor distinct from those of lesser stature. These alterations brought the Basilica Julii in line with the requirements of the ninth-century papal stational liturgy. The stational liturgy was hierarchically orga- nized from the beginning, but distinctions became sharper in the course of the early Middle Ages in accordance with the expansion of papal authority and changes in lay society. -

21 CHAPTER I the Formation of the Missionary Gaspar's Youth The

!21 CHAPTER I The Formation of the Missionary Gaspar’s Youth The Servant of God was born on January 6, 1786 and was baptized in the parochial church of San Martino ai Monti on the following day. On that occasion, he was given the names of the Holy Magi since the solemnity of the Epiphany was being celebrated. I received this information from the Servant of God himself during our familiar conversations. The Servant of God’s parents were Antonio Del Bufalo and Annunziata Quartieroni. I likewise learned from conversation with the father of the Servant of God as well as from him that at first Antonio was engaged in work in the fields but later, when his income was running short, he applied as a cook in service to the most excellent Altieri house. The Del Bufalos were upright people and were endowed sufficiently for their own maintenance as well as that of the family. They had two sons: one was named Luigi who married the upright young lady Paolina Castellini and were the parents of a daughter whose name was Luigia. The other son, our Servant of God. Luigi and Gaspar’s sister-in-law, as well as his father and mother, are now deceased. As far as I know, the aforementioned parents were full of faith, piety and other virtues made know to me not only by the Servant of God, honoring his father and mother, but also by Monsignor [Antonio] Santelli who was the confessor of his mother and a close friend of the Del Bufalo family. -

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry Director: Nathan T. Elkins, Ph.D The Mausoleum of Constantina and Helena in Rome once held two sarcophagi, but the second has never been properly identified. Using the decoration in the mausoleum and recent archaeological studies, this thesis identifies the probable design of the second sarcophagus. This reconstruction is confirmed by a fragment in the Istanbul Museum, which belonged to the lost sarcophagus. This is contrary to the current misattribution of the fragment to the sarcophagus of Constantine. This is only the third positively identified imperial sarcophagus recovered in Constantinople. This identification corrects misconceptions about both the design of the mausoleum and the history of the fragment itself. Using this identification, this thesis will also posit that an altar was originally placed in the mausoleum, a discovery central in correcting misconceptions about the 4th century imperial liturgy. Finally, it will posit that the decorative scheme of the mausoleum was not random, but was carefully thought out in connection to the imperial funerary liturgy itself. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS _____________________________________________ Dr. Nathan T. Elkins, Art Department APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM ____________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director DATE: _____________________ SARCOPHAGI IN CONTEXT: IDENTIFYING THE MISSING SARCOPHAGUS OF HELENA IN THE MAUSOLEUM OF -

LIST of PLATES 1. Aula Palatina, Trier, External and Internal View

vii LIST OF PLATES 1. Aula Palatina, Trier, external and internal view. Photo: J. Hawkes. 2. Basilica Nova, Rome, present view and reconstruction. Photo: author; reconstruction: J. Hawkes. 3. Fragments of the monumental statue of Constantine, Rome. Photo: J. Hawkes. 4. Constantine Arch, Rome. Photo: author. 5. Septimius Severus Arch, Rome. Photo: from Wikimedia Commons. 6. Constantine Arch, re-used Hadrianic tondoes. Photo: author. 7. Map of Constantinian foundations. Photo: from LEHMANN, edited by the author. 8. Plan of St Peter’s Basilica and of Lateran Basilica. Photo: from BRANDENBURG. 9. Plan of Circus Basilicas. Photo: from BRANDENBURG. 10. Santa Costanza, Rome, plan and aerial view. Photo: plan from BRANDENBURG; aerial view: J. Hawkes. 11. Examples of Roman Mausolea. a) Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella, Rome. Photo: author. b) mausoleum of Diocletian, Split. Photo: J. Hawkes. c) Mausoleum of Hadrian, Rome. Photo: author. 12. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaics, cross and lozenges. Photo: author. 13. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaic, vintage scene. Photo: author. 14. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaics, Traditio Legis. Photo: author. 15. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaics, Traditio Pacis. Photo: author. 16. St Peter’s Basilica, Rome, reconstruction of apse mosaic. Photo: from Christiana Loca. 17. San Paolo fuori le mura, Rome, apse mosaic. Photo: from BRANDENBURG. 18. Lateran Basilica, Rome, apse mosaic. Photo: from Wikimedia Commons. 19. Santa Pudenziana, Rome, apse mosaic. Photo: author. 20. Reconstruction of the fastigium at the Lateran Basilica. Photo: from TEASDALE SMITH. 21. Santa Sabina, Rome. Photo: author. 22. Plan of titulus Pammachii (SS Giovanni e Paolo), Rome. Photo: from DI GIACOMO. -

EARLY CHRISTIAN and BYZANTINE ART

Humanities 1B, Honors, Fall, 2015 Rostankowski EARLY CHRISTIAN and BYZANTINE ART Trajan 98-117 Antoninus Pius 138-161 Constantine 307-337 Hadrian 117-138 Marcus Aurelius 161-180 Justinian 527-565 Catacombs: Christian burial places, underground; hollowed out of the soft stone called tufa into rooms, with many small niches for burial. Loculus: catacomb burial niche Cubiculum: catacomb room or gallery. CONSTANTINE • Colossal seated sculpture (remaining head, appendages) • Arch of Constantine – used sculptural components from monuments of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius SCULPTURE • Good Shepherd – free standing • Christ enthroned, mid-4th century • Mithraic representations: Birth of Mithras, Life of Mithras from his altar, ascension of Mithras/Elijah’s ascent Sarcophagi: Mixed Styles • Sarcophagus with Angels (a la Nikes), 3rd century • Jonah Sarcophagus, early 4th century • Toils of Hercules sarcophagus, 4th century • Two Brothers sarcophagus, O.T. & N.T., 4th century • Madonna and the Magi Sarcophagus, early 5th century IVORY DIPTYCHS: Classical to non-classical • Nicomachi a& Symmachi – Bacchus priestess, Ceres priestess, late 4th century • Emperor Anastasius ca. 517 PAINTING - Catacombs • Catacombs of Saints Peter and Marcellinus, late 3rd century – 4th century • Jonah, Noah, Baptism of Christ, Raising of Lazarus, Adam & Eve • Mausoleum of the Julii, late 3rd century - Christ as Sol Invictus, mosaic. Iconoclasm • Christ, St. Catherine’s monastery, Mt. Sinai, Egypt, ca. 6th century • Virgin with Sts. Theodore and George, 6th century ARCHITECTURE Rome • Old St. Peter’s ca. 330 Basilica – a rectilinear building used by Roman government as a bureaucratic facility. Clerestory – raised roof above central aisle of a structure, usually with many windows, to allow light and air into a building. -

Velkommen Til

Velkommen til Romatur 1.–7.april 2017 Gruppe A #lvsroma2017 #lundeneset I dette heftet finner du program, praktiske opplysninger, deltakerliste m.m. Endringer vil mest sannsynlig forekomme. Følg derfor alltid med på beskjedene som blir gitt i plenum. Navn: Innholdsliste Innholdsliste ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Velkommen til Romatur! .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Reglement for studietur 2017 .................................................................................................................................. 2 Husk å ta med ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 La være å pakke ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Program og logg ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Måltider og mat ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Innreise og helse ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Medieval Rome and Its Monuments

Dr. Max Grossman Art History 5390 UTEP/John Cabot University Summer II, 2014 Tiber Campus, room 1.3 CRN# 34255 [email protected] MW 9:00am-1:00pm Medieval Rome and its Monuments Dr. Grossman earned his B.A. in Art History and English at the University of California- Berkeley, and his M.A., M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Art History at Columbia University. After seven years of residence in Tuscany, he completed his dissertation on the civic architecture, urbanism and iconography of the Sienese Republic in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. He served on the faculty of the School of Art and Design at San Jose State University in 2006-2009, taught art history for Stanford University in 2007-2009, and joined the Department of Art at the University of Texas at El Paso as Assistant Professor of Art History in 2009. During summers he is Coordinator of the UTEP Department of Art in Rome program and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art History at John Cabot University. He has presented papers and chaired sessions at conferences throughout the United States, including at the annual meeting of the Renaissance Society of America, and in Europe, at the annual meetings of the European Architectural History Network. In April 2012 in Detroit he chaired a session at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians: “Medieval Structures in Early Modern Palaces;” and in the following June he chaired a session at the 2nd International Meeting of the European Architectural History Network in Brussels: “Architecture and Territoriality in Medieval Europe,” which was published in the conference proceedings. -

Translations of the Sacred City Between Jerusalem and Rome

136 De Blaauw Chapter 6 Translations of the Sacred City between Jerusalem and Rome Sible de Blaauw Several cities and individual churches in the Middle Ages were associated with the idea of representing or incorporating Jerusalem in one manner or another. This widely attested phenomenon occurred in a large range of variants, de- pending on the ‘type’ of Jerusalem represented and the way in which the rep- resentation was made concrete.1 In this contribution, I aim to discuss one of the earliest, and perhaps one of the most notable cases of ‘being’ Jerusalem outside Jerusalem. The church leaders of Rome may have had very specific rea- sons for appropriating the significance of the historical Jerusalem as the an- cient capital of the Roman Empire. Moreover, they may have utilized very specific instruments in order for this claim to materialize. It was rooted in the idea that Christian Rome had been founded directly from Jerusalem by the mission of the apostles Peter and Paul. Rome was, in the words of Jennifer O’Reilly: ‘the western extremity of their evangelizing mission from the biblical centre of the earth at Jerusalem and became the new centre from which their papal successors continued the apostolic mission to the ends of the earth’.2 The existence of the apostles’ tombs, reinforced by the recollections of numer- ous Christian martyrs, was the fundamental factor in making Rome into the new spiritual capital of the Christian world. This claim urged Christian Rome to establish new terms for its relationship with what qualified, perhaps, as ‘the ideological centre of the Christian empire’ in Jerusalem.3 It has been argued that the Roman Church did so by a literal transfer of the significance of earthly Jerusalem to Rome, and hence by making Jerusalem superfluous. -

The Spolia Churches of Rome

fabricius maria hansen ISBNisbn 978-87-7124-210-2 978-87-7124-210-2 A tour around the Rome of old maria fabricius hansen The church-builders of the Middle 1 The Lateran Baptistery Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano Ages treated the architecture of 2 Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura Via Nomentana 349 ancient Rome like a quarry full of pre- 3 San Clemente Piazza di San Clemente fabricated building materials. This 4 Santa Costanza Via Nomentana 349 THE 9 788771 242102 resulted in some very eclectically 5 San Giorgio in Velabro Via del Velabro 3 and ingeniously constructed churches. THE SPOLIA 6 San Lorenzo fuori le Mura Piazzale del Verano 3 Søndergaard In The Spolia Churches of Rome we SPOLIA 7 Santa Maria in Cosmedin Piazza Bocca della Verità Trine learn of the principles for the distri- 8 Santa Maria in Trastevere Piazza di Santa Maria in Trastevere Photo: bution of these antique architectural elements and the significance of CHURCHES 9 San Nicola in Carcere Via del Teatro di Marcello 35 About the author breaking down and building on the past. 10 Santa Sabina Piazza Pietro d’Illiria Maria Fabricius Hansen is Also presented here is a selection of 11 Santo Stefano Rotondo Via di Santo Stefano Rotondo 6 eleven particularly beautiful churches an art historian and associate CHURCHES featuring a wide variety of spolia. OF ROME professor at the University of 1 Sant’ Adriano Foro Romano This book contains maps and other Copenhagen. She has written 2 San Bartolomeo all’Isola Piazza di San Bartolomeo all’Isola practical information which make it books and articles on the 3 San Benedetto in Piscinula Piazza in Piscinula the ideal companion when seeking out legacy and presence of antiquity 4 Santa Bibiana Via Giolitti 150 the past in modern-day Rome. -

Early Christian Architecture

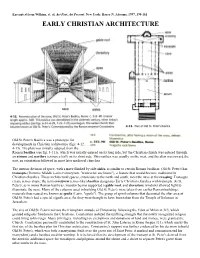

Excerpted from Wilkins, et. al, Art Past, Art Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997, 190-161 EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE Old St. Peter's Basilica was a prototype for developments in Christian architecture (figs. 4-12, 4-13). The plan was initially adapted from the Roman basilica (see fig. 3-111), which was usually entered on its long side, but the Christian church was entered through an atrium and narthex (entrance hall) on its short side. This narthex was usually on the west, and the altar was toward the east, an orientation followed in most later medieval churches. The interior division of space, with a nave flanked by side aisles, is similar to certain Roman basilicas. Old St. Peter's has transepts (from the Middle Latin transseptum, "transverse enclosure"), a feature that would become traditional in Christian churches. These architectural spaces, extensions to the north and south, meet the nave at the crossing. Transepts create across shape; the term cruciform (cross-like) basilica designates Early Christian churches with transepts. At St. Peter's, as in many Roman basilicas, wooden beams supported a gable roof, and clerestory windows allowed light to illuminate the nave. Many of the columns used in building Old St. Peter's were taken from earlier Roman buildings; materials thus reused are known as spolia (Latin, "spoils"). The group of spiral columns that decorated the altar area at Old St. Peter's had a special significance, for they were thought to have been taken from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The size of Old St. Peter's mirrors the triumphant attitude of Christianity following the Edict of Milan in 313, which granted religious freedom to the Christians. -

018-Santa Pudenziana

(018/14) Santa Pudenziana ! Main entrance of the church. Santa Pudenziana is a palaeo-Christian church dedicated to St Pudentiana, a legendary Roman martyr. It is also a converted 2nd century Roman bath-house, and one of the few ancient Roman buildings in Rome that has never been a ruin. It is located on the Viminale hill near Santa Maria Maggiore on today’s via Urbana, which corresponds to the old Vicus Patricius. It is now the national church of The Philippines, and is a minor basilica. History The church is one of the tituli, the first parish churches in Rome. It was known as the Titulus Pudentiana, named after the daughter of the Roman Senator St Pudens. It's mentioned in the Liber Pontificalis, and a tombstone from 384 refers to a man named Leopardus as lector de Pudentiana, this name refers to St Pudentiana. This latter form is first attested in the 4th century apse mosaic; earlier (018/14) documents and inscriptions use Pudentiana, who was a daughter of St Pudens and sister of St Praxedes (the nearby church of Santa Prassede is dedicated to her). Though the story of the sisters is somewhat uncertain, it is certain that there was a Christian named Pudens. The house was inherited by his son Novato, who built a bathhouse on the site. Pius I (141-155) later built an oratory in the bathouse, which was rebuilt in the fourth century. The first time this interpretation is mentioned in written sources is in a document from 745. The church is built over the house of St Pudens, which after the deaths of Peter and Paul was used as a 'house church'.