COMMUNITY PROFILE Draft (December 2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oahu Processing Centers Kauai Processing Centers

State of Hawaii Processing Centers Office Hours: 7:45 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Oahu Processing Centers Kauai Processing Centers Kapolei Processing Center (250) Kauai Processing Center East 601 Kamokila Boulevard, Room 117 Former Lihue Courthouse Building Kapolei, HI 96707 3059 Umi Street, Room A110 Phone: 692-8384 Fax: 692-7783 Lihue, HI 96766 Phone: 808-274-3371 Koolau Processing Center (306) & Fax: 808-335-8446 (390) Waikalua (306) Maui County Processing Centers 45-260 Waikalua Road Kaneohe, HI 96744 Maui Public Assistance (777) Phone: 233-3621 Fax: 233-3620 State Building 54 High St. #125 Luluku (390) Wailuku, HI 96793 45-513 Luluku Road Phone: 808-984-8300 Kaneohe, HI 96744 Fax: 808-984-8333 Phone: 233-5325 Fax: 233-5358 Molokai Unit (852) KPT Processing Center (160) 55 Makaena Pl. Rm. 1 1485 Linapuni Street, Suite 122 Kaunakakai, HI 96748 Honolulu, HI 96819 Phone: 808-553-1715 Phone: 832-3800 Fax: 832-3392 Fax: 808-553-1720 OR&L Processing Center (170) Mailing Address: 333 North King Street, Room 200 PO Box 70, Honolulu, HI 96817 Kaunakakai, HI 96748 Phone: 586-8047 Fax: 586-8138 Lanai Sub-Unit (853) Pohulani Processing Center (370) 730 Lanai Avenue 677 Queen Street, Suite 400B Lanai City, HI 96763 Honolulu, HI 96813 Phone: 808-565-7102 Phone: 587-5283 Fax: 587-5297 Fax: 808-565-6460 Wahiawa Processing Center (290) Mailing Address: 929 Center Street PO Box 631374 Wahiawa, HI 96786 Lanai City, HI 96763 Phone: 622-6315 Fax: 622-6484 Waianae Processing Center (270) 86-120 Farrington Highway, Suite A103 Waianae, HI 96792 Phone: 697-7881 Fax: 697-7184 Waipahu Processing Center (190) 94-275 Mokuola Street, Room 303A Waipahu, HI 96797 Phone: 675-0052 Fax: 675-0038 03/2018 State of Hawaii Processing Centers Office Hours: 7:45 a.m. -

Hale Ho′Ola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy

Hale Hoola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy June 2013 Hale Hoola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy Prepared by: Gerald A. Doeksen, Director Email: [email protected] and Cheryl St. Clair, Associate Director Email: [email protected] National Center for Rural Health Works Oklahoma State University Phone: 405-744-6083 R. Scott Daniels, Performance Improvement/Flex Coordinator Email: [email protected] Phone: 808-961-9460 and Gregg Kishaba, Rural Health Coordinator Email: [email protected] Phone: 808-586-5446 Hawaii State Department of Health State Office of Primary Care & Rural Health Deborah Birkmire-Peters, Program Director Pacific Basin Telehealth Resource Center John A. Burns School of Medicine University of Hawaii at Manoa Email: [email protected] Phone: 808-692-1090 June 2013 Hale Hoola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy Table of Contents I. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 II. Overview of Process ......................................................................................................... 2 III. Participants, Facilitators, and Medical Service Area ........................................................ 3 IV. About Hale Hoola Hamakua ............................................................................................ 7 V. Community Input Summary ............................................................................................ -

Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2015

STATEWIDE COMPREHENSIVE OUTDOOR RECREATION PLAN 2015 Department of Land & Natural Resources ii Hawai‘i Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2015 Update PREFACE The Hawai‘i State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2015 Update is prepared in conformance with a basic requirement to qualify for continuous receipt of federal grants for outdoor recreation projects under the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act, Public Law 88-758, as amended. Through this program, the State of Hawai‘i and its four counties have received more than $38 million in federal grants since inception of the program in 1964. The Department of Land and Natural Resources has the authority to represent and act for the State in dealing with the Secretary of the Interior for purposes of the LWCF Act of 1965, as amended, and has taken the lead in preparing this SCORP document with the participation of other state, federal, and county agencies, and members of the public. The SCORP represents a balanced program of acquiring, developing, conserving, using, and managing Hawai‘i’s recreation resources. This document employs Hawaiian words in lieu of English in those instances where the Hawaiian words are the predominant vernacular or when there is no English substitute. Upon a Hawaiian word’s first appearance in this plan, an explanation is provided. Every effort was made to correctly spell Hawaiian words and place names. As such, two diacritical marks, ‘okina (a glottal stop) and kahakō (macron) are used throughout this plan. The primary references for Hawaiian place names in this plan are the book Place Names of Hawai‘i (Pukui, 1974) and the Hawai‘i Board on Geographic Names (State of Hawai‘i Office of Planning, 2014). -

Inventory and Initial Screening Report

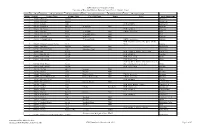

COUNTY OF HAWAII MASS TRANSIT AGENCY BUS STOP LOCATION STUDY INVENTORY AND INITIAL SCREENING REPORT Prepared by: SSFM International, Inc. 501 Sumner Street, Suite 620 Honolulu, HI 96817 Prepared for: County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency 630 E. Lanikaula Street Hilo, HI 96720 June 2010 Bus Stop Location Project for County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency Inventory and Initial Screening Report Introduction County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency Bus Stop Location Project Inventory and Initial Screening Report I. Introduction The County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency (MTA) currently operates on a flagstop basis. With increased usage and traffic, MTA is moving into a designated bus stop program. SSFM International, Inc. (SSFM) was contracted to identify locations for bus stops islandwide and to determine if locations warrant an official bus stop listed in the Hawaii County Code. Official bus stops will need to be Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant. This Inventory and Initial Screening Report constitutes the deliverable for Task One of the work program for this study. Based on field work conducted and meetings held with bus drivers, SSFM developed a complete inventory of bus stops islandwide. The inventory, consisting of approximately 575 stops, was then divided into priority and non-priority stops for the remainder of the work tasks in this study. Priority stops, totaling approximately 100 stops, were recommended based on surrounding land use, frequency, and local knowledge. The list of priority stops is shown in (Appendix 1). These stops handle the bulk of the ridership and are in close vicinity to schools, resorts, medical facilities, and urban centers. -

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island Status Key: 1 = Not Hawaiian; 2 = Not Reviewed; 3 = More Research Needed; 4 = HBGN Corrected; 5 = Already Correct in GNIS; 6 = Name Change Status Feat ID Feature Name Feature Class Corrected Name Source Notes USGS Quad Name 1 365008 1940 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 1 365009 1949 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 3 358404 Aa Falls Falls PNH: not listed Kukuihaele 5 358406 ʻAʻahuwela Summit ‘A‘ahuwela PNH Puaakala 3 358412 Aale Stream Stream PNH: not listed Piihonua 4 358413 Aamakao Civil ‘A‘amakāō PNH HBGN: associative Hawi 4 358414 Aamakao Gulch Valley ‘A‘amakāō Gulch PNH Hawi 5 358415 ʻĀʻāmanu Civil ‘Ā‘āmanu PNH Kukaiau 5 358416 ʻĀʻāmanu Gulch Valley ‘Ā‘āmanu Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Kukaiau PNH: Ahalanui, not listed, Laepao‘o; Oneloa, 3 358430 Ahalanui Laepaoo Oneloa Civil Maui Kapoho 4 358433 Ahinahena Summit ‘Āhinahina PNH Puuanahulu 5 1905282 ʻĀhinahina Point Cape ‘Āhinahina Point PNH Honaunau 3 365044 Ahiu Valley PNH: not listed; HBGN: ‘Āhiu in HD Kau Desert 3 358434 Ahoa Stream Stream PNH: not listed Papaaloa 3 365063 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Pahala 3 1905283 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Milolii PNH: not listed; HBGN: Āholehōlua if it is the 3 1905284 ʻĀhole Holua Locale slide, Āholeholua if not the slide Milolii 3 358436 Āhole Stream Stream PNH: Āhole, Maui Papaaloa 4 358438 Ahu Noa Summit Ahumoa PNH Hawi 4 358442 Ahualoa Civil Āhualoa PNH Honokaa 4 358443 Ahualoa Gulch Valley Āhualoa Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Honokaa -

SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, Died Feb. 8, 1993. He

SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, died Feb. 8, 1993. He was born in Luna, La Union, Philippines, and was formerly employed as a tailor at Andrade’s and Ross Sutherland. Survived by wife, Lourdes S.; daughters, Mrs. Domi (Rose) Timbresa and Mrs. Robert (Carmen) McDonald; six grandchildren; sister, Teresa of the Philippines; nieces and nephews. Friends may call from 6 to 9 p.m. Friday at Borthwick Mortaury; service 7 p.m. Mass 9:45 a.m. at St. Patrick Catholic Church. Burial at Diamond Head Memorial Park. Aloha attire. [Honolulu Advertiser 16 February 1993] SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, died Feb. 8, 1993. He was born in Luna, La Union, Philippines, and was formerly employed as a tailor at Andrade’s and Ross Sutherland. Friends may call from 6 to 9 p.m. Friday at Borthwick Mortuary; service 7 p.m. Mass 9:45 a.m. Saturday at St. Patrick Catholic Church. Burial at Diamond Head Memorial Park. Aloha attire. A recent obituary was incomplete. [Honolulu Advertiser 17 February 1993] Saballus, Doriel L., of Honolulu died last Thursday in St. Francis Hospital. Saballus, 46, was born in Berkeley, Calif. She is survived by husband Klaus; daughter Stephanie; parents Leo and Charlene Dwyer; and sister Leslie Dwyer. Services: 3 p.m. Saturday at Borthwick Mortuary. Calla after 2:30 p.m. Casual attire. No flowers. Memorial donations suggested to St. Francis Hospice. [Honolulu Star-Bulletin 7 January 1993] SABALLUS, DORIEL LEA, 46, of Honolulu, died Dec. 31, 1992. She was born in Berkeley, Calif. Survived by husband, Klaus; daughter, Stephanie; parents, Leo and Charlene Dwyer; sister, Leslie Dwyer; a nephew; au aunt. -

General Plan for the County of Hawai'i

COUNTY OF HAWAI‘I GENERAL PLAN February 2005 Pursuant Ord. No. 05-025 (Amended December 2006 by Ord. No. 06-153, May 2007 by Ord. No. 07-070, December 2009 by Ord. No. 09-150 and 09-161, June 2012 by Ord. No. 12-089, and June 2014 by Ord. No. 14-087) Supp. 1 (Ord. No. 06-153) CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1. Purpose Of The General Plan . 1-1 1.2. History Of The Plan . 1-1 1.3. General Plan Program . 1-3 1.4. The Current General Plan Comprehensive Review Program. 1-4 1.5. County Profile. 1-7 1.6. Statement Of Assumptions. 1-11 1.7. Employment And Population Projections . 1-12 1.7.1. Series A . 1-13 1.7.2. Series B . 1-14 1.7.3. Series C . 1-15 1.8. Population Distribution . 1-17 2: ECONOMIC 2.1. Introduction And Analysis. 2-1 2.2. Goals . .. 2-12 2.3. Policies . .. 2-13 2.4. Districts. 2-15 2.4.1. Puna . 2-15 2.4.2. South Hilo . 2-17 2.4.3. North Hilo. 2-19 2.4.4. Hamakua . 2-20 2.4.5. North Kohala . 2-22 2.4.6. South Kohala . 2-23 2.4.7. North Kona . 2-25 2.4.8. South Kona. 2-28 2.4.9. Ka'u. 2-29 3: ENERGY 3.1. Introduction And Analysis. 3-1 3.2. Goals . 3-8 3.3. Policies . 3-9 3.4. Standards . 3-9 4: ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 4.1. Introduction And Analysis. -

NKAWS Report Final Draft

Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Section 1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................3 Section 2 Types of Agriculture ............................................................................................5 2.1 Definition of Agriculture .........................................................................5 2.2 Crop Type ..............................................................................................10 2.3 Scale of Agriculture ...............................................................................12 2.31 Large Scale Agriculture .............................................................12 2.32 Mid-Size Agriculture .................................................................12 2.33 Small/Micro Agriculture ............................................................13 2.34 Agricultural Processing ..............................................................13 Section 3 Resources ...........................................................................................................15 3.1 Historical Systems .................................................................................15 3.2 Current Ditch System Intakes ................................................................17 3.3 Springs ...................................................................................................18 3.4 -

Waimanu Valley Oral History Report

WAIMANU VALLEY ORAL HISTORY REPORT prepared by . Kim Des Rochers for the Natural Area Reserve System Department of Land and Natural Resources, State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii and Sea Grant Extension Service, University of Hawaii at Manoa Honolulu, Hawaii August 1990 UNI H I-SEAGRANT -OT -89-02 WAIMANU VALLEY ORAL HISTORY REPORT prepared by Kim Des Rochers for the Natural Area Reserve System Department of Land and Natural Resources, State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii and Sea Grant Extension Service, University of Hawaii at Manoa Honolulu, Hawaii August 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................ 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND BACKGROUND .............................................. 2 METHODOLOGy ......................................................................................5 EARLY HISTORY OF WAIMANU VALLEy ..................................................... 7 BIBLIOGRAPHy ...................................................................................... 11 Biographical Summary for Eugene Burke .................................................... 1 6 Oral History Interviews with Eugene Burke ................................................. 17 Biographical Summary for Wilfred Mock Chew ........................................... 43 Oral History Interviews with Wilfred Mock Chew ........................................ 44 Biographical Summary for Lily Chong ........................................................ 79 Oral History Interview with Lily Chong ..................................................... -

Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30,1955

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 395 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 HAWAII UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 395 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 HAWAII By E. G. Bailey Washington, D. C., 1956 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 HAWAII By E. G. Bailey EXPLANATION This Index lists the streamflow and reservoir stations In Hawaii for which records have been or are to be published In reports of the Geological Survey for periods prior to September 30, 1955. The stations are listed In the downstream order. Starting at the headwater of each stream all stations are listed In a downstream direction. Tributary streams are Indicated by Indention and are Inserted between main-stem stations In the order In which they enter the main stream. To indicate the rank of any tributary on which a record is available and the stream to which it is immediately tributary, each indention in the listing of stations represents one rank. A stream name only is inserted where necessary for the purpose of showing the proper rank or order of tributaries. Station names are given in their most recently published forms. Parentheses around part of a station name indicate that the enclosed word or words were used in an earlier published name of the station or in a name under which records were published by some agency other than the Geological Survey. -

General Plan for the County of Hawai'i

COUNTY OF HAWAI‘I GENERAL PLAN February 2005 Pursuant Ord. No. 05-025 (Amended December 2006 by Ord. No. 06-153, May 2007 by Ord. No. 07-070, December 2009 by Ord. No. 09-150 and 09-161, and June 2012 by Ord. No. 12-089) Supp. 1 (Ord. No. 06-153) CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1. Purpose Of The General Plan . 1-1 1.2. History Of The Plan . 1-1 1.3. General Plan Program . 1-3 1.4. The Current General Plan Comprehensive Review Program. 1-4 1.5. County Profile. 1-7 1.6. Statement Of Assumptions. 1-11 1.7. Employment And Population Projections . 1-12 1.7.1. Series A . 1-13 1.7.2. Series B . 1-14 1.7.3. Series C . 1-15 1.8. Population Distribution . 1-17 2: ECONOMIC 2.1. Introduction And Analysis. 2-1 2.2. Goals . .. 2-12 2.3. Policies . .. 2-13 2.4. Districts. 2-15 2.4.1. Puna . 2-15 2.4.2. South Hilo . 2-17 2.4.3. North Hilo. 2-19 2.4.4. Hamakua . 2-20 2.4.5. North Kohala . 2-22 2.4.6. South Kohala . 2-23 2.4.7. North Kona . 2-25 2.4.8. South Kona. 2-28 2.4.9. Ka'u. 2-29 3: ENERGY 3.1. Introduction And Analysis. 3-1 3.2. Goals . 3-8 3.3. Policies . 3-9 3.4. Standards . 3-9 4: ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 4.1. Introduction And Analysis. 4-1 4.2. Goals . -

New Laws Benefit Working Families HONOLULU—Thanks to Union Political Action, Working Families Made Big Gains in This Year’S Legislative Session

OF May 2002 VOICETHE ILWU page 1 Volume 42 • No. 4 The VOICE of the ILWU—Published monthly except April by Hawaii Local 142, International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union May 2002 ADDRESS LABEL ADDRESS Union political action success New laws benefit working families HONOLULU—Thanks to union political action, working families made big gains in this year’s legislative session. Four significant pieces of new legislation sought by the ILWU were passed by state lawmakers. The Hawaii RX (SB 2520) and RX Expansion Program (HB 2834) will make prescription drugs more affordable for retirees and union members. Health Insurance Regulation (HB 1761) should help control the rapidly increasing cost of medical insurance, which affects wages and benefits on the job. A ban on discrimination based on genetic information (SB 2180) protects our members from unfair treatment by insurance companies and employers. nother very important recycling bill will help protect our A piece of legislation environment by reducing solid ILWU Local Executive Board Meeting Schedule: sought by the ILWU, which waste. •September 12-13, 2002 would protect workers when a In all, this year’s Legislative 10:00 a.m., Harry Kamoku Hall (Hawaii Division Hilo company is sold, narrowly failed session was very productive Office, 100 W. Lanikaula Street) passage by a single vote. The and beneficial for Hawaii’s Employment Security Bill (SB working families. See below for •December 12-13, 2002 2118) would have required a more information on these new Time and location for the December LEB meeting will new owner of a company to programs.