Caste Versus Class: Social Mobility in India, 1860- 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

Caste Versus Class: Social Mobility in India, 1860- 2012

Caste versus Class: Social Mobility in India, 1860- 2012 Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis Zach Landes, UCLA, Anderson School1 September, 2012 Using surname distributions, we compare long run social mobility rates for elite and underclass groups in India 1860-2012, with those of other societies such as Sweden and the USA. It is not clear whether recent social mobility rates in India should be higher or lower than in the West. The caste system notoriously embedded privilege in elite castes. But since Independence a quota of places in higher education, and in government jobs, have been reserved for the former lower castes. These quotas are now as great as 50% of such positions. Social mobility rates in India, however, prove to be extremely low, and not any higher now than under the Raj. Despite extensive social engineering India seems to be an unusually immobile society. We hypothesize that this immobility stems from continued strong marital endogamy in India. Introduction India is an interesting society in which to study rates of social mobility. On the one hand it entered the modern era with the legacy of the Hindu caste system, which found echoes also in Muslim society, which limited intermarriage, and even social intercourse, between those of different castes. This system of exclusion was so powerful that different castes and sub-castes, even within small geographic areas, have distinct DNA profiles. 2 There is the underfunded and poorly functioning primary and secondary public education system, which those of means have largely abandoned in favor of private schooling. Further many of the poor are located in rural areas for which educational provision is particularly poor, and private 1 With thanks to Lincoln Atkinson for his great help in digitizing the 2.2 million names of the Kolkata voters roll of 2010. -

On-The-Job Training

Health Response to Gender-Based Violence Competency Based Training Package for Blended Learning and On-the-Job-Training Facilitators’ Guide Government of Nepal Ministry of Health National Health Training Center 2016 Contributors List Mr. Achyut Lamichhane Former Director, National Health Training Center Mr. Anup Poudel International Organization for Migration Dr. Arun Raj Kunwar Kanti Children’s Hospital Ms. Beki Prasai United Nations Children’s Fund Ms. Bhawana Shrestha Dhulikhel Hospital Dr. Bimal Prasad Dhakal United Nations Population Fund Ms. Bindu Pokharel Gautam Suaahara, Save Ms. Chandra Rai Jhpiego Nepal Department of Forensic Medicine, Institute of Dr. Harihar Wasti Medicine Mr. Hem Raj Pandey Family Health Division Dr. Iswor Upadhyay National Health Training Center Ms. Jona Bhattarai Jhpiego Ms. Kamala Dahal Department of Women and Children SSP Krishna Prasad Gautam Nepal Police Dr. Kusum Thapa Jhpiego Mr. Madhusudan Amatya National Health Training Center Ms. Marte Solberg United Nations Population Fund Ms. Mina Bhandari Sunsari Hospital Dr. Mita Rana Tribhuwan University and Teaching Hospital Mr. Mukunda Sharam Population Division Ms. Myra Betron Jhpiego Mr. Parba Sapkota Population Division Dr. Rakshya Joshi Obstetrician and Gynecologist Nepal Health Sector Support Program/Ministry of Ms. Rekha Rana Health and Population Department of Forensic Medicine, Institute of Dr. Rijen Shrestha Medicine Mr. Robert J Lamburne UK Department for International Development Ms. Sabita Bhandari Lawyer Ms. Sandhya Limbu Jhpiego Dr. Saroja Pandey Paroparkar Maternity and Women’s Hospital Ms. Shakuntala Prajapati Management Division Ms. Suku Lama Paroparkar Maternity and Women’s Hospital Dr. Shilu Aryal Family Health Division Dr. Shilu Adhikari United Nations Population Fund National Health, Education, Information and Mr. -

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

July-September 2016, Volume 18 No. 1

DIALOGUE QUARTERLY Volume-18 No. 1 July-September, 2016 Subscription Rates : For Individuals (in India) Single issue Rs. 30.00 Annual Rs. 100.00 For 3 years Rs. 250.00 For Institutions: Single Issue Rs. 60.00 in India, Abroad US $ 15 Annual Rs. 200.00 in India, Abroad US $ 50 For 3 years Rs. 500.00 in India, Abroad US $ 125 All cheques and Bank Drafts (Account Payee) are to be made in the name of “ASTHA BHARATI”, Delhi. Advertisement Rates : Outside back-cover Rs. 25, 000.00 Per issue Inside Covers Rs. 20, 000.00 ,, Inner page coloured Rs. 15, 000.00 ,, Inner full page Rs. 10, 000.00 ,, DIALOGUE QUARTERLY Editorial Advisory Board Mrinal Miri Jayanta Madhab Editor B.B. Kumar Consulting Editor J.N. Roy ASTHA BHARATI DELHI The views expressed by the contributors do not necessarily represent the view-point of the journal. © Astha Bharati, New Delhi Printed and Published by Dr. Lata Singh, IAS (Retd.) Secretary, Astha Bharati Registered Office: 27/201 East End Apartments, Mayur Vihar, Phase-I Extension, Delhi-110096. Working Office: 23/203 East End Apartments, Mayur Vihar, Phase-I Extension, Delhi-110096 Phone : 91-11-22712454 e-mail : [email protected] web-site : www. asthabharati.org Printed at : Nagri Printers, Naveen Shahdara, Delhi-32 Contents Editorial Perspective 7 Intellectual mercenaries, the Post-Independence Avataras of the Hindu Munshis 1. North-East Scan Assam Floods: Another Perspective 11 Patricia Mukhim Manipur: Maintaining Sanity in the Times of Chaos 14 Pradip Phanjoubam 2. Pre-Paninian India Linguistic Awareness from Rig Veda to Mahabharata 17 Dr. -

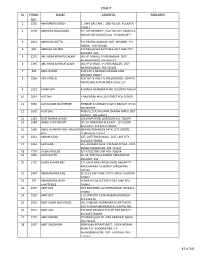

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447 -

'Netaji's Life Was More Important Than the Legends and Myths' Page 1 of 4

The Telegraph Page 1 of 4 Issue Date: Sunday , July 10 , 2011 ‘Netaji’s life was more important than the legends and myths’ Miami-based economist turned film-maker Suman Ghosh — who has also made a documentary on Amartya Sen — was in conversation with Sugata Bose, Netaji’s grandnephew, about the historian’s His Majesty’s Opponent — Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle Against Empire on the morning of the launch of the Penguin book. Metro sat in on the Netaji adda. Excerpts… Suman Ghosh: You are a direct descendent of Subhas Chandra Bose and your father (Sisir Kumar Bose) was involved in the freedom struggle with him. Did you worry about objectivity in treating a subject that was so close to you? Sugata Bose: I made a conscious decision to write this book as a historian. Not as a Sugata Bose speaks with (right) family member. My father always used to tell me that Netaji believed that his country and Suman Ghosh at Netaji Bhavan. family were coterminous. So if I’m a member of the Bose family by an accident of birth so Picture by Bishwarup Dutta are all of the people of India. In some ways, if there is a problem of objectivity it would apply to most people and scholars of the subcontinent. But I felt I had acquired the necessary critical distance from my subject to embark on this project when I did. Ghosh: Netaji has always been shrouded in myths and mysteries. He has primarily been characterised as a revolutionary and a warrior. -

Town Survey Report Forbesganj, Series-4, Bihar

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES-4 BIHAR Part-X B TOWN SURVEY REPORT FORBESGANJ Draft by: Edited by: Supervised by ~. P. N. SINHA S. C. SAXENA V.K.BHARGAVA Assistant Director Deputy Director Deputy Director of Census Operations, Bihar of Census Operations, Bihar of Census Operations, Bihar CONTENTS Page Foreword ... (v) Preface (vii) Chapter I Introduction 1-5 Chapter II History of growth of the town 7-8 Chapter III Amenities and services-History of growth and present position 9-17 Chapter IV Economic life of the town 19-42 Chapter V Ethnic and selected socio-demographic characteristics of the population 43-63 Chapter VI Migration and settlement of families 64-75 Chapter VII Neighbourhood pattern 76-86 Chapter VIII Family life in the town 87-93 Chapter IX Housing and materia I culture 95-102 Chapter X Organisation of power and prestige 103-106 Chapter XI Leisure and recreation, social participation, social awareness, religion and crime. 107-112 Chapter XII Linkage and Continua 113-126 Chapter XIII Conclusion 127-128 Map & Charts Showing Urban Land use Showing Pre-urban area Showing Public utility services FORBESGANJ TOWN URBAN LAND USE (NOT TO SCALE) N i BOUNDARY> TOWN WNlD ROAD Rs ,., RAILWAY .. BUSINESS A~EA re-.-el I!.!..!.!I ADMINISTAATIVE AREA ~ RESIDENTIAL AREA • EDUCATIONAL AREA ~ INDUSTRIAL AREA D AGRICULTURAL AREA D UNCLASSIFIED AREA I REGISTRY OFFICE VETERINARY 2 POST OfFICE POLICE STATION 1 HOSPITAL 6 INSPECTION BUNGALOW ~ GRAVE YARD FORBESGANJ TOWN PERI· URBAN AREA Furlongs 8 4 (0 1 Miles t:::t;:!:~~~=::::::l Km, I o 1 Kms. / \ \ ,.1 __ ._ ........ -

Biography and Homoeopathy in Bengal

Biography and Homoeopathy in Bengal: Colonial Lives of a European Heterodoxy1 Short Title: Biography and Homoeopathy in Bengal Centre for Research in Arts Social Science and Humanities, University of Cambridge, UK Email: [email protected] Despite being recognised as a significant literary mode in understanding the advent of modern self, biographies as a genre have received relatively less attention from South Asian historians. Likewise, histories of science and healing in British India have largely ignored the colonial trajectories of those sectarian, dissenting, supposedly pseudo-sciences and medical heterodoxies that flourished in Europe since the late eighteenth century. This article addresses these gaps in the historiography to identify biographies as a principal mode through which an incipient, ‘heterodox’ western science like homoeopathy could consolidate and sustain itself in Bengal. In recovering the cultural history of a category that the state archives render largely invisible, this article contends biographies as more than a mere repository of individual lives, and to be a veritable site of power. In bringing histories of print and publishing, histories of medicine and histories of life writing practices together, it pursues two broad themes: First, it analyses the sociocultural strategies and networks by which scientific doctrines and concepts are translated across cultural borders. It explores the relation between medical commerce, print capital and therapeutic knowledge, to illustrate that acculturation of medical science necessarily drew upon and reinforced local constellations of class, kinship and religion. Second, it simultaneously reflects upon the expanding genre of homoeopathic biographies published since the mid nineteenth century: on their features, relevance and functions, examining in particular, the contemporary status of biography vis-à-vis ‘history’ in writing objective pasts.