Mona Lisa Is Always Happy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Alter Schützt Vor Torschluss Nicht

Bestimmungen: Unerlaubte Aufführungen, unerlaubtes Abschreiben, Vervielfältigen, Verleihen der Rollen müssen als Verstoß gegen das Urheberrecht verfolgt werden. Alle Rechte, auch die Übersetzung, Rundfunk Verfilmung, und Fernsehübertragung sind vorbehalten. Das Recht der Aufführung erteilt ausschließlich der Verlag. Info-Box 0540 Bestell-Nummer: 0540 Komödie: 2 Akte cke.de - Bühnenbilder: 1 Alter schützt vor Torschluss Spielzeit: 90 Min. nicht Rollen: 6 Je öller je döller Frauen: 4 Männer: 2 Rollensatz: 7 Hefte Komödie in 3 Akten Preis Rollensatz 125,00€ Aufführungsgebühr pro von Aufführung: 10% der Einnahmen Indra Janorschke und Dario Weberg mindestens jedoch 85,00€ theaterverlag-theaterstü - www.nrw-hobby.de 6 Rollen für 4 Frauen und 2 Männer 1 Bühnenbild Als der ehemalige und inzwischen abgebrannte Schlagerstar Edwin eine alte Villa seiner verstorbenen Tante Ottilie erbt, scheint sich seine finanzielle Situation endlich zu bessern. Und auch wenn seine Enkelinnen Mona und Lisa begeistert von dem alten und leicht unheimlichen Haus sind, steht fest: Edwin muss verkaufen und von dem Geld www.theaterstücke-online.de - - de seine Schulden bezahlen. Als jedoch sein verhasster Bruder Eugen plötzlich auftaucht und behauptet, ebenfalls Erbe der Villa zu sein, zerbrechen seine Träume jäh. Und dabei bleibt es nicht. Nach und nach tauchen weitere Erben auf. Als sich die Obdachlose Renate weigert, dem Verkauf des Hauses zuzustimmen, bleibt den Rentnern nur noch eine Lösung: sie müssen eine Wohngemeinschaft in der Villa gründen, um ihre eigenen Wohnungen, die sie schon lange nicht mehr finanzieren können, zu kündigen. Und dann treibt auch noch ein Einbrecher sein Unwesen in der Stadt und die alte Augusta schleppt erstaunlich viel Geld mit sich herum… - - www.mein-theaterverlag. -

Eurovision Song Comtest Complete 88 89

1980s !1 Eurovision Song Contest 1988 Björn Nordlund !1 Björn Nordlund 10 juni 2018 1988 Ne Partez pas sans moi Eurovision, sida !1 Björn Nordlund 10 juni 2018 1988 Suddenly it happens For you all whom read all the pages my number one song each year not exactly celebrate grand success. So all of a sudden it happens my favorite song ended up as number one, and lets face it… WOW, who knew anything about Celine Dion back in 1988? The Swiss entry, ”Ne partez pas sans moi” stole the crown this year at the end of the voting, thanks to Yugoslavias jury for some reason agreed with the French singer Gerard Lenorman that his entry was of the same class as ”My way” (”Comme d´habitude”). And I can imagine that the UK singer Scott Fitzgerald was a bit surprised over the outcome. In ans case, not only Celine Dion started her way to success this year, also Lara Fabian entered, but for Luxembourg. So how did my list compare to the final result this year. We had some really good entries but 1988 must be seen as a middle year even if songs like ”Pu og peir”, ”Nauravat Silmät muistetaan”, ”La chica que yo quiro” and ”Ka du se hva jeg sa”. Sweden sent our number one musical star Mr Tommy Körberg who went from the stages of the London musical scene to Eurovision (his second try) and for Swedish media it was all in the bag, Eurovision from Sweden 1989.. It turned out to be very wrong and the Swedish delegation blamed Tommys bad cold and voice problems. -

REFLECTIONS 148X210 UNTOPABLE.Indd 1 20.03.15 10:21 54 Refl Ections 54 Refl Ections 55 Refl Ections 55 Refl Ections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS MERCI CHÉRIE – MERCI, JURY! AUSGABE 2015 | ➝ Es war der 5. März 1966 beim Grand und belgischen Hitparade und Platz 14 in Prix d’Eurovision in Luxemburg als schier den Niederlanden. Im Juni 1966 erreichte Unglaubliches geschah: Die vielbeachte- das Lied – diesmal in Englisch von Vince te dritte Teilnahme von Udo Jürgens – Hill interpretiert – Platz 36 der britischen nachdem er 1964 mit „Warum nur war- Single-Charts. um?“ den sechsten Platz und 1965 mit Im Laufe der Jahre folgten unzähli- SONG CONTEST CLUBS SONG CONTEST 2015 „Sag‘ ihr, ich lass sie grüßen“ den vierten ge Coverversionen in verschiedensten Platz belegte – bescherte Österreich end- Sprachen und als Instrumentalfassungen. Wien gibt sich die Ehre lich den langersehnten Sieg. In einem Hier bestechen – allen voran die aktuelle Teilnehmerfeld von 18 Ländern startete Interpretation der grandiosen Helene Fi- der Kärntner mit Nummer 9 und konnte scher – die Versionen von Adoro, Gunnar ÖSTERREICHISCHEN schließlich 31 Jurypunkte auf sich verei- Wiklund, Ricky King und vom Orchester AUSSERDEM nen. Ein klarer Sieg vor Schweden und Paul Mauriat. Teilnehmer des Song Contest 2015 – Rückblick Grand Prix 1967 in Wien Norwegen, die sich am Podest wiederfan- Hier sieht man das aus Brasilien stam- – Vorentscheidung in Österreich – Das Jahr der Wurst – Österreich und den. mende Plattencover von „Merci Cherie“, DAS MAGAZIN DES der ESC – u.v.m. Die Single erreichte Platz 2 der heimi- das zu den absoluten Raritäten jeder Plat- schen Single-Charts, Platz 2 der deutschen tensammlung zählt. DIE LETZTE SEITE ections | Refl AUSGABE 2015 2 Refl ections 2 Refl ections 3 Refl ections 3 Refl ections INHALT VORWORT PRÄSIDENT 4 DAS JAHR DER WURST 18 GRAND PRIX D'EUROVISION 60 HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN 80 „Building bridges“ – Ein Lied Pop, Politik, Paris. -

Universidade Do Estado Do Rio De Janeiro Centro De Educação E Humanidades Faculdade De Comunicação Social

Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Centro de Educação e Humanidades Faculdade de Comunicação Social Vanessa de Freitas Silva #museumselfie: sociabilidades mediadas por imagens conectadas no Instagram Rio de Janeiro 2018 Vanessa de Freitas Silva #museumselfie: sociabilidades mediadas por imagens conectadas no Instagram Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre, ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação, da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Área de Concentração: Comunicação Social. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fernando do Nascimento Gonçalves Rio de Janeiro 2018 CATALOGAÇÃO NA FONTE UERJ / REDE SIRIUS / BIBLIOTECA CEH/A S586 Silva, Vanessa de Freitas. #museumselfie: sociabilidades mediadas por imagens conectadas no Instagram / Vanessa de Freitas Silva. – 2018. 160 f. Orientador: Fernando do Nascimento Gonçalves Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Faculdade de Comunicação Social. 1. Comunicação Social – Teses. 2. Fotografia – Teses. 3. Museu – Teses. 4. Redes Sociais on-line – Teses. I. Gonçalves, Fernando do Nascimento. II. Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Faculdade de Comunicação Social. III. Título. es CDU 316.6 Autorizo, apenas para fins acadêmicos e científicos, a reprodução total ou parcial desta dissertação, desde que citada a fonte. ___________________________________ _______________ Assinatura Data Vanessa de Freitas Silva #museumselfie: sociabilidades mediadas por imagens conectadas no Instagram Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre, ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação, da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Área de Concentração: Comunicação Social. Aprovada em 28 de fevereiro de 2018 Banca examinadora: ____________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Fernando do Nascimento Gonçalves (Orientador) PPGCOM – UERJ ____________________________________________________ Profª. Drª. -

Listeréalisateurs

A Crossing the bridge : the sound of Istanbul (id.) 7-12 De lʼautre côté (Auf der anderen Seite) 14-14 DANIEL VON AARBURG voir sous VON New York, I love you (id.) 10-14 DOUGLAS AARNIOKOSKI Sibel, mon amour - head-on (Gegen die Wand) 16-16 Highlander : endgame (id.) 14-14 Soul kitchen (id.) 12-14 PAUL AARON MOUSTAPHA AKKAD Maxie 14 Le lion du désert (Lion of the desert) 16 DODO ABASHIDZE FEO ALADAG La légende de la forteresse de Souram Lʼétrangère (Die Fremde) 12-14 (Ambavi Suramis tsikhitsa - Legenda o Suramskoi kreposti) 12 MIGUEL ALBALADEJO SAMIR ABDALLAH Cachorro 16-16 Écrivains des frontières - Un voyage en Palestine(s) 16-16 ALAN ALDA MOSHEN ABDOLVAHAB Les quatre saisons (The four seasons) 16 Mainline (Khoon Bazi) 16-16 Sweet liberty (id.) 10 ERNEST ABDYJAPOROV PHIL ALDEN ROBINSON voir sous ROBINSON Pure coolness - Pure froideur (Boz salkyn) 16-16 ROBERT ALDRICH Saratan (id.) 10-14 Deux filles au tapis (The California Dolls - ... All the marbles) 14 DOMINIQUE ABEL TOMÁS GUTIÉRREZ ALEA voir sous GUTIÉRREZ La fée 7-10 Rumba 7-14 PATRICK ALESSANDRIN 15 août 12-16 TONY ABOYANTZ Banlieue 13 - Ultimatum 14-14 Le gendarme et les gendarmettes 10 Mauvais esprit 12-14 JIM ABRAHAMS DANIEL ALFREDSON Hot shots ! (id.) 10 Millenium 2 - La fille qui rêvait dʼun bidon dʼessence Hot shots ! 2 (Hot shots ! Part deux) 12 et dʼune allumette (Flickan som lekte med elden) 16-16 Le prince de Sicile (Jane Austenʼs mafia ! - Mafia) 12-16 Millenium 3 - La reine dans le palais des courants dʼair (Luftslottet som sprangdes) 16-16 Top secret ! (id.) 12 Y a-t-il quelquʼun pour tuer ma femme ? (Ruthless people) 14 TOMAS ALFREDSON Y a-t-il un pilote dans lʼavion ? (Airplane ! - Flying high) 12 La taupe (Tinker tailor soldier spy) 14-14 FABIENNE ABRAMOVICH JAMES ALGAR Liens de sang 7-14 Fantasia 2000 (id. -

Proquest Dissertations

VEUILLEZ NOTER QUE CETTE THÈSE EST INCOMPLÈTE PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS THESIS IS INCOMPLETE - le résumé est manquant - abstract is missing THÈSE DÉPOSÉE À L'ÉCOLE DES ÉTUDES SUPÉRIEURES ET DE LA RECHERCHE DANS LE CADRE DE LA MAÎTRISE ES ARTS EN SOCIOLOGIE (g) WILLIAM De GASTON Sous la direction du professeur ROBERTO MIGUELEZ UNIVERSITÉ D'OTTAWA AVRIL 1999 UMI Number: EC56052 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dépendent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complète manuscript and there are missing pages, thèse will be noted. AIso, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC56052 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC AH rights reserved. This microform édition is protected against unauthorized copying underTitle 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 AnnArbor, Ml 48106-1346 LA SOCIOLOGIE DU SOURIRE Un sourire ne coûte rien, mais il crée beaucoup: il ne dure qu'un instant, et le souvenir en persiste parfois toute une vie. Dale Carnegie Comment se faire des amis. A Edem, Mon frère. A Roberto Miguelez, Mon maître, reconnaissance et respect SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPITRE I - CADRE THÉORIQUE ET MÉTHODOLOGIQUE .. 7 1. Ethnométhodologie 7 2. Phénoménologie 14 3. Théorie de la communication 18 CHAPITRE II - ÉTUDE SOCIOLOGIQUE DU SOURIRE 25 1. Socialisation du sourire et les contextes culturels 26 2. -

Allemagne 13

25e Eurovisie Songfestival 1980 Finale - Le samedi 19 avril 1980 à La Haye - Présenté par : Marlous Fluitsma Du bist musik (Tu es musique) 1 - Autriche par Blue Danube 64 points / 8e Auteur/Compositeur : Klaus-Peter Sattler Petr'oil 2 - Turquie par Ajda Pekkan 23 points / 15e Auteur : Şanar Yurdatapan / Compositeur : Atilla Özdemiroglu Ωτοστοπ - Autostop - (Auto-stop) 3 - Grèce par Anna Vissy & Epikouri 30 points / 13e Auteur : Rony Sofou / Compositeur : Jick Nakassian Le papa pingouin 4 - Luxembourg par Sophie & Magali 56 points / 9e Auteurs : Pierre Delanoë, Jean-Paul Cara / Compositeurs : Ralph Siegel, Bernd Meinunger (Bitakat hob - (Message d'amour - ﺐﺣ ﺔﻗﺎﻂﺑ 5 - Maroc par Samira Bensaïd 7 points / 18e Auteur : Malou Rouane / Compositeur : Abdel Ati Amenna Non so che darei (Que ne donnerais-je pas) 6 - Italie par Alan Sorrenti 87 points / 6e Auteur/Compositeur : Alan Sorrenti Tænker altid på dig (Je penserais toujours à toi) 7 - Danemark par Bamses Venner 25 points / 14e Auteur : Flemming Bamse Jørgensen / Compositeur : Bjarne Gren Jensen Just nu (C'est maintenant) 8 - Suède par Tomas Ledin 47 points / 10e Auteur/Compositeur : Tomas Ledin Cinéma 9 - Suisse par Paola 104 points / 4e Auteurs : Peter Reber, Véronique Müller / Compositeur : Peter Reber Huilumies (Le flûtiste) 10 - Finlande par Vesa Matti Loiri 6 points / 19e Auteur : Vexi Salmi / Compositeur : Aarno Raninen Samiid ædnan (Terre lappone) 11 - Norvège par Sverre Kjelsberg & Mattis Hætta 15 points / 16e Auteur : Ragnar Olsen / Compositeur : Sverre Kjelsberg Theater (Théatre) -

Dunkleundschwerezeitenstehe

DunkleDunkle UndUnd SchwereSchwere ZeitenZeiten StehenStehen Bevor.Bevor. PRESSEINFORMATION Harry Potter Publishing Rights © J.K. Rowling WARNER BROS. PICTURES präsentiert eine HEYDAY FILMS-Produktion einen Film von MIKE NEWELL (Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire) DANIEL RADCLIFFE RUPERT GRINT EMMA WATSON Mit ROBBIE COLTRANE RALPH FIENNES MICHAEL GAMBON BRENDAN GLEESON JASON ISAACS GARY OLDMAN ALAN RICKMAN MAGGIE SMITH TIMOTHY SPALL Regie MIKE NEWELL Produzent DAVID HEYMAN nach dem Roman von J.K. ROWLING Drehbuch STEVE KLOVES Executive Producers DAVID BARRON und TANYA SEGHATCHIAN Kamera ROGER PRATT, B.S.C. Produktionsdesign STUART CRAIG Schnitt MICK AUDSLEY Co-Produzent PETER MacDONALD Kostümdesign JANY TEMIME Musik PATRICK DOYLE Deutscher Kinostart: 17. November 2005 im Verleih von Warner Bros. Pictures Germany a division of Warner Bros. Entertainment GmbH www.harrypotter.de 6 inhalt | harry potter und der feuerkelch harry potter und der feuerkelch | über die produktion/inhalt 7 Große Halle füllen – alle warten atemlos auf die Wahl ihrer Champions. verschreckt an Dumbledore. Doch selbst der ehrwürdige Direktor muss Barty Crouch (ROGER LLOYD PACK) vom Zaubereiministerium und Pro- zugeben, dass er mit seinem Latein am Ende ist. fessor Dumbledore leiten die Zeremonie bei Kerzenlicht, und die Span- Während Harry und die übrigen Champions sich mit der letzten Aufgabe nung steigt, als der verzauberte Feuerkelch je einen Schüler der Schulen und den eigenwilligen Hecken des unheimlichen Labyrinths herumschla- für den Wettkampf auswählt. In -

Fee-Alexandra Haase BEAUTY and ESTHETICS MEANINGS of AN

Fee-Alexandra Haase BEAUTY AND ESTHETICS MEANINGS OF AN IDEA AND CONCEPT OF THE SENSES. An Introduction to an Esthetic Communication Concept Facing the Perspectives Of Its Theory, History, and Cultural Traditions of the Beautiful. 1 The Definition of Beauty is That Definition is none - Of Heaven, easing Analysis, Since Heaven and He are one. Emily Dickinson - The Definition of Beauty is 2 – CONTENTS – 1. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................4 2. THE THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE: THE BODY OF ESTHETICS CATEGORIES AND ELEMENTS FOR MEANINGS OF ESTHETICS IN THEORIES AND RESEARCH OR ‚HOW TO GET AN APPROACH TO ESTHETICS?’ ......................................................................5 2.1. Elements of Esthetics....................................................................................................9 2.2. The Senses or ‚How do Esthetic Phenomena Come To Us?’ .......................................11 2.3. The Perception or ‚How Do We Notice Esthetic Phenomena?’....................................26 2.4. Categories of Reception or ‚How Do We React On Esthetic Phenomena?’..................33 2.5. Esthetic Values or ‘How Do We Judge On Esthetic Phenomena?’ ...............................41 3. THE PERSPECTIVE OF APPLICATION: OBJECTS OF ESTHETICS FORMAL CATEGORIES FOR MEANINGS OF THE BEAUTIFUL. APPLIED ESTHETICS OR ‘HOW DO WE USE ESTHETICS’?........................................54 3.1. Applied Esthetics........................................................................................................60 -

“Multiplen Intelligenzen”?

Reihe „Pädagogik und Fachdidaktik für Lehrerlnnen“ Herausgegeben vom Institut für „Unterricht und Schulentwicklung“ der Fakultät für Interdisziplinäre Forschung und Fortbildung der Universität Klagenfurt Mag. Maximilian Leonhardmair Howard Gardners Konzept der multiplen Intelligenzen und seine Anwendung in dem Klassenlektüreprojekt „Gioconda Smile“ by Aldous Huxley PFL Englisch Klagenfurt, 2011 Betreuung: Dr. Christine Lechner Die Universitätslehrgänge „Pädagogik und Fachdidaktik für Lehrer/-innen― (PFL) sind interdisziplinäre Lehrerfortbildungsprograrnme des Instituts für Interdisziplinäre Forschung und Fortbildung―. Die Durchführung der Lehrgänge erfolgt mit Unterstützung des BMUKK. 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung (Mein Forschungsanliegen - Hintergrund der Themenstellung/ Lehrsituation) Abstract / Kurzfassung Howard Gardners Konzept der multiplen Intelligenzen und seine Anwendung in dem Klassenlektüreprojekt „Gioconda Smile“ by Aldous Huxley 3 1. Was bedeutet das Konzept der „multiplen Intelligenzen“? 7 1.1 Der Begriff Intelligenz 7 1.2 Kriterien zur Identifikation von Intelligenzen 9 2. Die Darstellung der Intelligenzen nach Howard Gardner 13 2.1 Sprachlich-linguistische Intelligenz 13 2.2 Logisch-mathematische Intelligenz 14 2.3 Musikalisch-rhythmische Intelligenz 15 2.4 Bildlich-räumliche Intelligenz 15 2.5 Körperlich-kinästhetische Intelligenz 16 2.6 Interpersonale Intelligenz 17 2.7 Intrapersonale Intelligenz 17 2.8 Naturalistische Intelligenz 18 3. Schülerbefragung: Wo liegen meine Stärken? 19 3.1 Auswertung der Befragung der acht Intelligenzen 19 3.2 Detailauswertung von Abschnitt 5: Interpersonale Intelligenz 21 3.3 Übersicht über die Reihung aller acht Intelligenzen 22 4. Projekt „Gioconda Smile“ 23 4.1. Talking about and answering a list of questions 23 4.2 Creating and solving crossword puzzles 24 4.3 Mind-map der Charaktere und ihrer Beziehungen 24 4.4 Places and settings mit Kurzkommentar 24 4.5 Rekonstruierung des Gesamttextes 24 4.6 Lesen von Textsequenzen mit verteilten Rollen 25 4.7 Musikalische Hörverständnisaufgabe mit Einsetzübungen 25 5. -

The Nul-Pointers Biographies

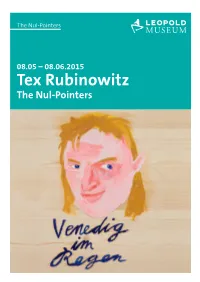

The Nul-Pointers 08.05 – 08.06.2015 Tex Rubinowitz The Nul-Pointers FUD LECLERC (1924–2012) DE SPELBREKERS representing Belgium with »Ton Nom« in Luxembourg, 1962 representing the Netherlands with »Katinka« in Luxembourg, 1962 Fud Leclerc was once the pianist of the famous chanteuse The Dutch duo Theo Rekkers (1923–2012) and Huug Kok (1918– Juliette Greco and competed in the contest four times. His last 2011) met during World War II in a forced labour camp in Germa- appearance in 1962 saw him go out with the dubious honour ny. After the War they started their singing career that brought of having become the first »nul-pointer« ever (the entries from them to the Eurovision in 1962. Unfortunately this was the first Spain, the Netherlands and Austria would follow him the very year in which the term »nul pointer« appeared. Nevertheless, same evening). After travelling around the world he returned to »Katinka« proved a success within the Netherlands. After years Belgium and began a new career as a building contractor. of releasing further singles to declining interest, they decided in the mid-1970s to move into music management. VICTOR BALAGUER (1921–1984) representing Spain with »Llámame« in Luxembourg, 1962 ANNIE PALMEN (1926–2000) The namesake of a 19th century Catalan folk hero, Victor was representing the Netherlands with »Een speeldos« in London, 1963 known as an adaptable singer who moved between popular mu- Annie was already a successful singer when she presented her sic and zarzuela, singing in Spanish as well as Catalan. Follow- song »Een Speeldos« in London, one of four songs which failed ing his Eurovision appearance, Balaguer returned to performing to score that year. -

The Glasgow Diaries Hal Cassidy

The GlasgOw Diaries Hal Cassidy Capitalism's admirers tend to equate calls for reform with looming socialism. But most reformers, seeking a fair shake for workers in this downsizing era, simply ask if capitalism is to be our slave or master Confidential report condems £6bn waterway scheme as deep slash across the nation's fabric Plan for English 'Panama Canal' to be scrutinized Why Cherie is The Big Earner happy in the Let him teach others how to sell background Chirac 'backs Major' in Is the Stone a fight over working hit or a myth? hours Guard of honour for the final mile Card sellers show little charity Shoppers go gullibly into sales frenzy Yesterdays shops threw their doors open to millions of bargain hunters. But should we believe those 'once only' offers? Major Tom Burns: give refs a voice floats on Cadete 'goal' the last straw stock market high Rangers shares CLINTON, THE LOVE-CHILD soar after AND THE MISSING HOOKER win over Celtic Double nightmare that looms over Bill's big day HE JUST LURVED SCOTLAND BUT CAN YOU SEE HIM LIVING HERE? A Jackson farce that masked the cold truth THE TRENDIEST WALL IN TOWN Trainspotting is this craze Attack of the 60ft among English kids for woman having trains run over them THE RUNAWAY GENE GENIE Dolly the sheep raises the possibilities of cloning children, growing new limbs and tuning the human species to higher levels of intelligence Crathie members fear restoration row could lead to Queen using Balmoral chapel Organs' threat to royal worship Exclusive: research shows telephone charges bear no relation to actual costs Calling for change SCOTTISH CHAPEL HOLDS CLUE TO CENTURIES-OLD MYSTERY, SAY INVESTIGATORS Turin Shroud? It must Go-ahead for rival lottery be Jacques the Mason that's faster on the draw All-green homes for people ..