The Other Frankfurt School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thejudaic Element in the Teachings of the Frankfurt School

The Judaic Element in the Teachings of the Frankfurt School BY JUDITH MARCUS AND ZOLTAN TAR INTRODUCTION j In dealing with the question of the Judaic element in the teachings of the Frankfurt School, one does well to proceed as the Hebrew script does, that is, from right to left.* First, there should be a highly compressed account ofwhat on or publication of the Frankfurt School was about, and, second, an explanation ofwhat is meant by the teachings of the Frankfurt School, that is, the theoretical content of the School. Finally, we take up the main business at hand, that is, the examination of the Judaic element in the work of three Frankfurt School theorists: Max Horkheimer, Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno and Erich Fromm. Even in the case ofsuch a relatively modest and at times descriptive task as personal use only. Citati this has to be, a social scientist and historian of ideas is bound to refer to the rums. Nutzung nur für persönliche Zwecke. methodology applied. The approach will follow several lines of investigation, tten permission of the copyright holder. most notably that of the sociology of knowledge, i.e., the "existential determination of ideas" approach. If Hegel is right in saying that "to comprehend what is, is the task of philosophy [and] whatever happens, every individual is a child of his time; and philosophy is [but] its own time comprehended in thought",' then this is particularly true of the thinkers of the Frankfurt School. We might add to Hegel's dictum that each social philosophy is and remains limited and/or influenced by the historical conditions, and, subjectively, by the physical and mental constitution of its originator. -

Key Texts and Contributions to a Critical Theory of Society

1 Introduction: Key Texts and Contributions to a Critical Theory of Society Beverley Best, Werner Bonefeld and Chris O’Kane The designation of the Frankfurt School as a known by sympathisers as ‘Café Marx’. It ‘critical theory’ originated in the United was the first Marxist research institute States. It goes back to two articles, one writ- attached to a German University. ten by Max Horkheimer and the other by Since the 1950s, ‘Frankfurt School’ criti- Herbert Marcuse, that were both published in cal theory has become an established, inter- Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (later Studies nationally recognised ‘brand name’ in the in Philosophy and Social Science) in 1937.1 social and human sciences, which derives The Zeitschrift, published from 1932 to from its institutional association in the 1920s 1941, was the publishing organ of the and again since 1951 with the Institute Institute for Social Research. It gave coher- for Social Research in Frankfurt, (West) ence to what in fact was an internally diverse Germany. From this institutional perspec- and often disagreeing group of heterodox tive, it is the association with the Institute Marxists that hailed from a wide disciplinary that provides the basis for what is considered spectrum, including social psychology critical theory and who is considered to be a (Fromm, Marcuse, Horkheimer), political critical theorist. This Handbook works with economy and state formation (Pollock and and against its branded identification, concre- Neumann), law and constitutional theory tising as well as refuting it. (Kirchheimer, Neumann), political science We retain the moniker ‘Frankfurt School’ (Gurland, Neumann), philosophy and sociol- in the title to distinguish the character of its ogy (Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse), culture critical theory from other seemingly non- (Löwenthal, Adorno), musicology (Adorno), traditional approaches to society, including aesthetics (Adorno, Löwenthal, Marcuse) the positivist traditions of Marxist thought, and social technology (Gurland, Marcuse). -

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, and the FRANKFURT SCHOOL by Ryan

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sociology – Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson Through a systematic analysis of the works of Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Erich Fromm using historical methods, I document how early critical theory can conceptually and theoretically inform sociological examinations of human-nature relations. Currently, the first-generation Frankfurt School’s work is largely absent from and criticized in environmental sociology. I address this gap in the literature through a series of articles. One line of analysis establishes how the theories of Horkheimer, Adorno, and Marcuse are applicable to central topics and debates in environmental sociology. A second line of analysis examines how the Frankfurt School’s explanatory and normative theories of human- animal relations can inform sociological animal studies. The third line examines the place of nature in Fromm’s social psychology and sociology, focusing on his personality theory’s notion of “biophilia.” Dedicated to 바다. See you soon. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my dissertation committee immense gratitude for offering persistent intellectual and emotional support. Linda Kalof overflows with kindness and her gentle presence continually put my mind at ease. It was an honor to be the mentee of a distinguished scholar foundational to the formation of animal studies. Tom Dietz is the most cheerful person I have ever met and, as the first environmental sociologist to integrate ideas from critical theory with a bottomless knowledge of the environmental social sciences, his insights have been invaluable. -

Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School: Introduction

wendy brown Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School: Introduction Feminism is a revolt against decaying capitalism. —Marcuse There is a quaintness to Herbert Marcuse’s manifesto on behalf of “feminist socialism,” here reprinted for the first time since its appearance thirty years ago in Women’s Studies. It is not only an open- hearted and hopeful little effort at theoretically codifying the expansive revolutionary promise of the second wave of the Women’s Movement, a promise that would soon be dashed from within and without. Marcuse’s political and philosophical assumptions were also vulnerable to emerg- ing postfoundational critiques of the humanist subject, progressive his- toriography, and their entailments: essentialized identities, totalizing identities, undeconstructed binary oppositions, faith in emancipation, and revolution. Openhearted, hopeful, vulnerable, imaginative, revolution- ary: precisely the qualities Marcuse thought feminism brought to the unyielding and ultimately unemancipatory rationality of a masculinist radical politics, on the one hand, and a dreamless liberal egalitarianism, on the other. This unemancipatory rationality was the terrain that the Frankfurt School worked from every direction, as it upturned the myth of Volume 17, Number 1 doi 10.1215/10407391-2005-001 © 2006 by Brown University and d i f f e r e n c e s : A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/differences/article-pdf/17/1/1/405311/diff17-01_02BrownFpp.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School Enlightenment reason, integrated psychoanalysis into political philosophy, pressed Nietzsche and Weber into Marx, attacked positivism as an ideology of capitalism, theorized the revolutionary potential of high art, plumbed the authoritarian ethos and structure of the nuclear family, mapped cultural and social effects of capital, thought and rethought dialectical materialism, and took philosophies of aesthetics, reason, and history to places they had never gone before. -

Online Finding

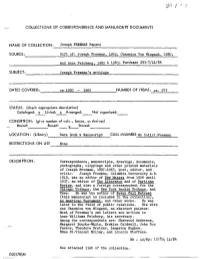

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

Cultural Marxism and Cultural Studies Douglas Kellner

Cultural Marxism and Cultural Studies Douglas Kellner (http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/) Many different versions of cultural studies have emerged in the past decades. While during its dramatic period of global expansion in the 1980s and 1990s, cultural studies was often identified with the approach to culture and society developed by the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in Birmingham, England, their sociological, materialist, and political approaches to culture had predecessors in a number of currents of cultural Marxism. Many 20th century Marxian theorists ranging from Georg Lukacs, Antonio Gramsci, Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, and T.W. Adorno to Fredric Jameson and Terry Eagleton employed the Marxian theory to analyze cultural forms in relation to their production, their imbrications with society and history, and their impact and influences on audiences and social life. Traditions of cultural Marxism are thus important to the trajectory of cultural studies and to understanding its various types and forms in the present age. The Rise of Cultural Marxism Marx and Engels rarely wrote in much detail on the cultural phenomena that they tended to mention in passing. Marx’s notebooks have some references to the novels of Eugene Sue and popular media, the English and foreign press, and in his 1857-1858 “outline of political economy,” he refers to Homer’s work as expressing the infancy of the human species, as if cultural texts were importantly related to social and historical development. The economic base of society for Marx and Engels consisted of the forces and relations of production in which culture and ideology are constructed to help secure the dominance of ruling social groups. -

Otto Kirchheimer and Carl Schmitt After 1945.” Redescriptions: Political Thought, Conceptual History and Feminist Theory 24(1): 4–26

REDESCRIPTIONS Buchstein, Hubertus. 2021. “The Godfather of Left-Schmittianism? Political Thought, Conceptual History and Feminist Theory Otto Kirchheimer and Carl Schmitt after 1945.” Redescriptions: Political Thought, Conceptual History and Feminist Theory 24(1): 4–26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33134/rds.320 RESEARCH The Godfather of Left-Schmittianism? Otto Kirchheimer and Carl Schmitt after 1945 Hubertus Buchstein Greifswald University, DE [email protected] In the vast secondary literature on Carl Schmitt as well as on the Frankfurt School, the political and legal thinker Otto Kirchheimer is described as a forerunner of contemporary Left-Schmittianism. This view is sometimes expanded in the litera- ture to the personal relationship between Schmitt and Kirchheimer after 1945 as well. A closer look at Kirchheimer’s late work, at his unpublished correspondence with Schmitt, and at additional unpublished sources contradicts such an interpre- tation. In fact, Kirchheimer strongly attacked Schmittianism in German debates on constitutional theory after 1945. This article finally uncovers the extent to which Schmitt tried to instrumentalize his former doctoral student to pursue his political rehabilitation in the Federal Republic via the United States. Kirchheimer, however, took a firm stand against this attempt. In his defense of modern parliamentary democracy, Kirchheimer definitely sided with the political left of his times; but he did so without any flirtation with Schmittianism. Keywords: Otto Kirchheimer; Carl Schmitt; Left-Schmittianism; antisemitism; West German political and legal thought I. Introduction: Against Some Legends The work of Carl Schmitt (1888–1985) has become a point of reference for a growing number of contemporary political theorists on the left. -

The Copyright of This Recording Is Vested in the BECTU History Project

Elizabeth Furse Tape 1 Side A This recording was transcribed by funds from the AHRC-funded ‘History of Women in British Film and Television project, 1933-1989’, led by Dr Melanie Bell (Principal Investigator, University of Leeds) and Dr Vicky Ball (Co-Investigator, De Montfort University). (2015). COPYRIGHT: No use may be made of any interview material without the permission of the BECTU History Project (http://www.historyproject.org.uk/). Copyright of interview material is vested in the BECTU History Project (formerly the ACTT History Project) and the right to publish some excerpts may not be allowed. CITATION: Women’s Work in British Film and Television, Elizabeth Furse, http://bufvc.ac.uk/bectu/oral-histories/bectu-oh [date accessed] By accessing this transcript, I confirm that I am a student or staff member at a UK Higher Education Institution or member of the BUFVC and agree that this material will be used solely for educational, research, scholarly and non-commercial purposes only. I understand that the transcript may be reproduced in part for these purposes under the Fair Dealing provisions of the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act. For the purposes of the Act, the use is subject to the following: The work must be used solely to illustrate a point The use must not be for commercial purposes The use must be fair dealing (meaning that only a limited part of work that is necessary for the research project can be used) The use must be accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement. Guidelines for citation and proper acknowledgement must be followed (see above). -

Vol. X. No.1 CONTENTS No Rights for Lynchers...• . . • 6

VoL. X. No.1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2, 19:34 No Rights for Lynchers. • . • 6 The New Republic vs. the Farmers •••••• 22 Roosevelt Tries Silver. 6 Books . .. .. • . • . • 24 Christmas Sell·Out ••••.......••..•.•••• , 7 An Open Letter by Granville Hicks ; Fascism in America, ••..• by John Strachey 8 Reviews by Bill Dunne, Stanley Burn shaw, Scott Nearing, Jack Conroy. The Reichstag Trial •• by Leonard L Mins 12 Doves in the Bull Ring .. by John Dos Passos 13 ·John Reed Club Art Exhibition ......... ' by Louis Lozowick 27 Is Pacifism Counter-Revolutionary ••••••• by J, B. Matthews 14 The Theatre •.•••... by William Gardener 28 The Big Hold~Up •••••••••••••••••••.•• 15 The Screen ••••••••••••• by Nathan Adler 28 Who Owns Congress •• by Marguerite Young 16 Music .................. by Ashley Pettis 29 Tom Mooney Walks at Midnight ••.••.•• Cover •••••• , ••••••• by William Gropper by Michael Gold 19 Other Drawinp by Art Young, Adolph The Farmen Form a United Front •••••• Dehn, Louis Ferstadt, Phil Bard, Mardi by Josephine Herbst 20 Gasner, Jacob Burck, Simeon Braguin. ......1'11 VOL, X, No.2 CONTENTS 1934 The Second Five~ Year Plan ........... , • 8 Books •••.•.••.••.•••••••••••••••••.••• 25 Writing and War ........ Henri Barbusse 10 A Letter to the Author of a First Book, by Michael Gold; Of the World Poisons for People ••••••••• Arthur Kallet 12 Revolution, by Granville Hicks; The Union Buttons in Philly ••••• Daniel Allen 14 Will Durant of Criticism, by Philip Rahv; Upton Sinclair's EPIC Dream, "Zafra Libre I" ••.••••..•• Harry Gannes 15 by William P. Mangold. A New Deal in Trusts .••• David Ramsey 17 End and Beginning .• Maxwell Bodenheim 27 Music • , • , •••••••••••••••. Ashley Pettis 28 The House on 16th Street ............. -

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

Cold War PS MB 10/27/03 8:28 PM Page 146 House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) Excerpt from “One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism in the U.S.A.” Reprinted from Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts From Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, published in 1971 “[Question:] Why ne Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- shouldn’t I turn “O nism in the U.S.A.” was the first in a series of pam- Communist? [Answer:] phlets put out by the House Un-American Activities Commit- You know what the United tee (HUAC) to educate the American public about communism in the United States. In May 1938, U.S. represen- States is like today. If you tative Martin Dies (1900–1972) of Texas managed to get his fa- want it exactly the vorite House committee, HUAC, funded. It had been inactive opposite, you should turn since 1930. The HUAC was charged with investigation of sub- Communist. But before versive activities that posed a threat to the U.S. government. you do, remember you will lose your independence, With the HUAC revived, Dies claimed to have gath- ered knowledge that communists were in labor unions, gov- your property, and your ernment agencies, and African American groups. Without freedom of mind. You will ever knowing why they were charged, many individuals lost gain only a risky their jobs. In 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration membership in a Act, known as the Smith Act. The act made it illegal for an conspiracy which is individual to be a member of any organization that support- ruthless, godless, and ed a violent overthrow of the U.S. -

Report on Civil Rights Congress As a Communist Front Organization

X Union Calendar No. 575 80th Congress, 1st Session House Report No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION INVESTIGATION OF UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES IN THE UNITED STATES COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ^ EIGHTIETH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Public Law 601 (Section 121, Subsection Q (2)) Printed for the use of the Committee on Un-American Activities SEPTEMBER 2, 1947 'VU November 17, 1947.— Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1947 ^4-,JH COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES J. PARNELL THOMAS, New Jersey, Chairman KARL E. MUNDT, South Dakota JOHN S. WOOD, Georgia JOHN Mcdowell, Pennsylvania JOHN E. RANKIN, Mississippi RICHARD M. NIXON, California J. HARDIN PETERSON, Florida RICHARD B. VAIL, Illinois HERBERT C. BONNER, North Carolina Robert E. Stripling, Chief Inrestigator Benjamin MAi^Dt^L. Director of Research Union Calendar No. 575 SOth Conokess ) HOUSE OF KEriiEfcJENTATIVES j Report 1st Session f I1 No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION November 17, 1917. —Committed to the Committee on the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. Thomas of New Jersey, from the Committee on Un-American Activities, submitted the following REPORT REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS 205 EAST FORTY-SECOND STREET, NEW YORK 17, N. T. Murray Hill 4-6640 February 15. 1947 HoNOR.\RY Co-chairmen Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Dr. Harry F. Ward Chairman of the board: Executive director: George Marshall Milton Kaufman Trea-surcr: Field director: Raymond C. -

Next Witness. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Berthold Brecht. the CHAIRMAN

Next witness. committee whether or not you are a citizen of the United States? Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Berthold Brecht. Mr. BRECHT. I am not a citizen of the United States; I have The CHAIRMAN. Mr. Becht, will you stand, please, and raise only my first papers. your right hand? Mr. STRIPLING. When did you acquire your first papers? Do you solemnly swear the testimony your are about to give is the Mr. BRECHT. In 1941 when I came to the country. truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God? Mr. STRIPLING. When did you arrive in the United States? Mr. BRECHT. I do. Mr. BRECHT. May I find out exactly? I arrived July 21 at San The CHAIRMAN. Sit down, please. Pedro. Mr. STRIPLING. July 21, 1941? TESTIMONY OF BERTHOLD BRECHT (ACCOMPANIED BY Mr. BRECHT. That is right. COUNSEL, MR. KENNY AND MR. CRUM) Mr. STRIPLING. At San Pedro, Calif.? Mr. Brecht. Yes. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Brecht, will you please state your full Mr. STRIPLING. You were born in Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany, name and present address for the record, please? Speak into the on February 10, 1888; is that correct? microphone. Mr. BRECHT. Yes. Mr. BRECHT. My name is Berthold Brecht. I am living at 34 Mr. STRIPLING. I am reading from the immigration records — West Seventy-third Street, New York. I was born in Augsburg, Mr. CRUM. I think, Mr. Stripling, it was 1898. Germany, February 10, 1898. Mr. BRECHT. 1898. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Brecht, the committee has a — Mr. STRIPLING. I beg your pardon.