The Copyright of This Recording Is Vested in the BECTU History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

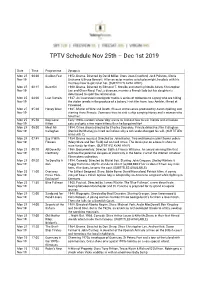

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

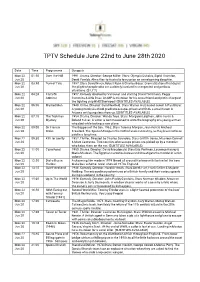

TPTV Schedule June 22Nd to June 28Th 2020

TPTV Schedule June 22nd to June 28th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 22 01:50 Over The Hill 1991. Drama. Director: George Miller. Stars: Olympia Dukakis, Sigrid Thornton, Jun 20 Derek Fowlds. Alma flies to Australia to surprise an unwelcoming daughter. Mon 22 03:50 Turn of Fate 1957. Stars David Niven, Robert Ryan & Charles Boyer. Dramatizations that depict Jun 20 the plight of people who are suddenly involved in unexpected and perilous situations. (S1, E7) Mon 22 04:20 Carry On 1957. Comedy directed by Val Guest and starring David Tomlinson, Peggy Jun 20 Admiral Cummins & Alfie Bass. An MP is mistaken for his naval friend and put in charge of the fighting ship HMS Sherwood! (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 22 06:00 Marked Men 1940. Crime. Director: Sam Newfield. Stars Warren Hull, Isabel Jewell & Paul Bryar. Jun 20 A young medical-school graduate escapes prison and finds a small haven in Arizona until gangsters show up. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 22 07:10 The Teckman 1954. Drama. Director: Wendy Toye. Stars: Margaret Leighton, John Justin & Jun 20 Mystery Roland Culver. A writer is commissioned to write the biography of a young airman who died while testing a new plane. Mon 22 09:00 Sir Francis The Beggars of the Sea. 1962. Stars Terence Morgan, Jean Kent & Michael Jun 20 Drake Crawford. The Spanish troops in the Netherlands ear mutiny, as they have not been paid in a long time. Mon 22 09:30 Kill Her Gently 1957. Thriller. Directed by Charles Saunders. Stars Griffith Jones, Maureen Connell Jun 20 & Marc Lawrence. -

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

Cold War PS MB 10/27/03 8:28 PM Page 146 House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) Excerpt from “One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism in the U.S.A.” Reprinted from Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts From Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, published in 1971 “[Question:] Why ne Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- shouldn’t I turn “O nism in the U.S.A.” was the first in a series of pam- Communist? [Answer:] phlets put out by the House Un-American Activities Commit- You know what the United tee (HUAC) to educate the American public about communism in the United States. In May 1938, U.S. represen- States is like today. If you tative Martin Dies (1900–1972) of Texas managed to get his fa- want it exactly the vorite House committee, HUAC, funded. It had been inactive opposite, you should turn since 1930. The HUAC was charged with investigation of sub- Communist. But before versive activities that posed a threat to the U.S. government. you do, remember you will lose your independence, With the HUAC revived, Dies claimed to have gath- ered knowledge that communists were in labor unions, gov- your property, and your ernment agencies, and African American groups. Without freedom of mind. You will ever knowing why they were charged, many individuals lost gain only a risky their jobs. In 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration membership in a Act, known as the Smith Act. The act made it illegal for an conspiracy which is individual to be a member of any organization that support- ruthless, godless, and ed a violent overthrow of the U.S. -

MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

#10 silent comedy, slapstick, music hall. CONTENTS 3 DVD news 4Lost STAN LAUREL footage resurfaces 5 Comedy classes with Britain’s greatest screen co- median, WILL HAY 15 Sennett’s comedienne MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian 19 Did STAN LAUREL & LUPINO LANE almost form a team? 20 Revelations and rarities : LAUREL & HARDY, RAYMOND GRIFFITH, WALTER FORDE & more make appearances at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY 25The final part of our examination of CHARLEY CHASE’s career with a look at his films from 1934-40 31 SCREENING NOTES/DVD reviews: Exploring British Comedies of the 1930s . MORE ‘ACCIDENTALLY CRITERION PRESERVED’ GEMS COLLECTION MAKES UK DEBUT Ben Model’s Undercrank productions continues to be a wonderful source of rare silent comedies. Ben has two new DVDs, one out now and another due WITH HAROLD for Autumn release. ‘FOUND AT MOSTLY LOST’, presents a selection of pre- LLOYD viously lost films identified at the ‘Mostly Lost’ event at the Library of Con- gress. Amongst the most interesting are Snub Pollard’s ‘15 MINUTES’ , The celebrated Criterion Collec- George Ovey in ‘JERRY’S PERFECT DAY’, Jimmie Adams in ‘GRIEF’, Monty tion BluRays have begun being Banks in ‘IN AND OUT’ and Hank Mann in ‘THE NICKEL SNATCHER’/ ‘FOUND released in the UK, starting AT MOSTLY LOST is available now; more information is at with Harold Lloyd’s ‘SPEEDY’. www.undercrankproductions.com Extra features include a com- mentary, plus documentaries The 4th volume of the ‘ACCIDENTALLY PRESERVED’ series, showcasing on Lloyd’s making of the film ‘orphaned’ films, many of which only survive in a single print, is due soon. -

Report on Civil Rights Congress As a Communist Front Organization

X Union Calendar No. 575 80th Congress, 1st Session House Report No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION INVESTIGATION OF UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES IN THE UNITED STATES COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ^ EIGHTIETH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Public Law 601 (Section 121, Subsection Q (2)) Printed for the use of the Committee on Un-American Activities SEPTEMBER 2, 1947 'VU November 17, 1947.— Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1947 ^4-,JH COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES J. PARNELL THOMAS, New Jersey, Chairman KARL E. MUNDT, South Dakota JOHN S. WOOD, Georgia JOHN Mcdowell, Pennsylvania JOHN E. RANKIN, Mississippi RICHARD M. NIXON, California J. HARDIN PETERSON, Florida RICHARD B. VAIL, Illinois HERBERT C. BONNER, North Carolina Robert E. Stripling, Chief Inrestigator Benjamin MAi^Dt^L. Director of Research Union Calendar No. 575 SOth Conokess ) HOUSE OF KEriiEfcJENTATIVES j Report 1st Session f I1 No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION November 17, 1917. —Committed to the Committee on the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. Thomas of New Jersey, from the Committee on Un-American Activities, submitted the following REPORT REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS 205 EAST FORTY-SECOND STREET, NEW YORK 17, N. T. Murray Hill 4-6640 February 15. 1947 HoNOR.\RY Co-chairmen Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Dr. Harry F. Ward Chairman of the board: Executive director: George Marshall Milton Kaufman Trea-surcr: Field director: Raymond C. -

Next Witness. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Berthold Brecht. the CHAIRMAN

Next witness. committee whether or not you are a citizen of the United States? Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Berthold Brecht. Mr. BRECHT. I am not a citizen of the United States; I have The CHAIRMAN. Mr. Becht, will you stand, please, and raise only my first papers. your right hand? Mr. STRIPLING. When did you acquire your first papers? Do you solemnly swear the testimony your are about to give is the Mr. BRECHT. In 1941 when I came to the country. truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God? Mr. STRIPLING. When did you arrive in the United States? Mr. BRECHT. I do. Mr. BRECHT. May I find out exactly? I arrived July 21 at San The CHAIRMAN. Sit down, please. Pedro. Mr. STRIPLING. July 21, 1941? TESTIMONY OF BERTHOLD BRECHT (ACCOMPANIED BY Mr. BRECHT. That is right. COUNSEL, MR. KENNY AND MR. CRUM) Mr. STRIPLING. At San Pedro, Calif.? Mr. Brecht. Yes. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Brecht, will you please state your full Mr. STRIPLING. You were born in Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany, name and present address for the record, please? Speak into the on February 10, 1888; is that correct? microphone. Mr. BRECHT. Yes. Mr. BRECHT. My name is Berthold Brecht. I am living at 34 Mr. STRIPLING. I am reading from the immigration records — West Seventy-third Street, New York. I was born in Augsburg, Mr. CRUM. I think, Mr. Stripling, it was 1898. Germany, February 10, 1898. Mr. BRECHT. 1898. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Brecht, the committee has a — Mr. STRIPLING. I beg your pardon. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: from the BELLY of the HUAC: the RED PROBES of HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philos

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE BELLY OF THE HUAC: THE RED PROBES OF HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Directed By: Dr. Maurine Beasley, Journalism The House Un-American Activities Committee, popularly known as the HUAC, conducted two investigations of the movie industry, in 1947 and again in 1951-1952. The goal was to determine the extent of communist infiltration in Hollywood and whether communist propaganda had made it into American movies. The spotlight that the HUAC shone on Tinsel Town led to the blacklisting of approximately 300 Hollywood professionals. This, along with the HUAC’s insistence that witnesses testifying under oath identify others that they knew to be communists, contributed to the Committee’s notoriety. Until now, historians have concentrated on offering accounts of the HUAC’s practice of naming names, its scrutiny of movies for propaganda, and its intervention in Hollywood union disputes. The HUAC’s sealed files were first opened to scholars in 2001. This study is the first to draw extensively on these newly available documents in an effort to reevaluate the HUAC’s Hollywood probes. This study assesses four areas in which the new evidence indicates significant, fresh findings. First, a detailed analysis of the Committee’s investigatory methods reveals that most of the HUAC’s information came from a careful, on-going analysis of the communist press, rather than techniques such as surveillance, wiretaps and other cloak and dagger activities. Second, the evidence shows the crucial role played by two brothers, both German communists living as refugees in America during World War II, in motivating the Committee to launch its first Hollywood probe. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

The Cultural Cold War the CIA and the World of Arts and Letters

The Cultural Cold War The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters FRANCES STONOR SAUNDERS by Frances Stonor Saunders Originally published in the United Kingdom under the title Who Paid the Piper? by Granta Publications, 1999 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2000 Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press oper- ates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in in- novative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450 West 41st Street, 6th floor. New York, NY 10036 www.thenewpres.com Printed in the United States of America ‘What fate or fortune led Thee down into this place, ere thy last day? Who is it that thy steps hath piloted?’ ‘Above there in the clear world on my way,’ I answered him, ‘lost in a vale of gloom, Before my age was full, I went astray.’ Dante’s Inferno, Canto XV I know that’s a secret, for it’s whispered everywhere. William Congreve, Love for Love Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................... v Introduction ....................................................................1 1 Exquisite Corpse ...........................................................5 2 Destiny’s Elect .............................................................20 3 Marxists at -

Now in It's 30 Year 25Th

Now in it’s 30th Year 25th - 27th October 2019 Welcome to the third progress report for the thirtieth festival. We are pleased add another two guests have confirmed that can attend to complete the line-up for the festival. It just keeps getting better. How are you going to fit it all in? Writer/Director/Special Dez Skinn, Effects and Make-up Publisher— back by Design supremo popular request to Sergio Stivaletti finish the stories he started last year. Help us celebrate the past thirty years by sharing your memories of festivals past. Send us your photographs and tell us what you remember. We hope to include some of these in the festival programme book. Guests The following guests have confirmed that they can attend (subject to work commitments). Lawrence Deirdre Giannetto Janina Gordon Clark Costello De Rossi Faye Dana Pauline Norman J. Gillespie Peart Warren 1 A message from the 3 Festival’s Chairman 2010 As we approach Festival number 30 - one of the best 2011 things we can look forward to is getting to see a lot of faces who have been around for at least 20 or more years, who, like me, are beginning to show that it isn’t just films that age. 2012 It has been a hard task to find new guests but we managed it again this year – in fact we have some real quality guests in both the acting profession and the 2013 behind-the-screen work. When I, Tony, Harry and Dave Trengove started this event we were thinking it might continue for about 5 2014 years - not 30! So I would like to say that the success of the event, has been firmly in the hands of those mentioned and several other persons (some unfortunately no longer with us). -

James Bond's Films

James Bond’s Films Picture : all-free-download.com October 5th, 2012 is the Global James Bond Day, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the first James Bond film: Dr. No (ISAN 0000-0000-FD39-0000-2-0000-0000-V), released in UK on October 5th, 1962. James Bond, code name 007, is a fictional character created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short story collections. Since 1962, 25 theatrical films have been produced around the character of James Bond. Sean Connery has been the first James Bond. He also played this role in other 6 films. Waiting for the next James Bond film, Skyfall, directed by Sam Mendes and starring Daniel Craig, and that will be released in October 2012, ISAN-IA joins the celebration for the Global James Bond Day by publishing a list of the past films dedicated to the most popular secret agent with the related identifying ISANs. Happy Birthday, Mr. Bond! Actor as Year Original Title Director ISAN James Bond 1962 Dr. No Terence Young Sean Connery 0000-0000-FD39-0000-2-0000-0000-V 1963 From Russia with Love Terence Young Sean Connery 0000-0000-D3B0-0000-6-0000-0000-J 1964 Goldfinger Guy Hamilton Sean Connery 0000-0000-39C7-0000-P-0000-0000-0 1965 Thunderball Terence Young Sean Connery 0000-0000-D3B1-0000-B-0000-0000-4 1967 You Only Live Twice Lewis Gilbert Sean Connery 0000-0000-7BDF-0000-L-0000-0000-B More titles ISAN International Agency Follows us on 1 A rue du Beulet CH- 1203 Geneva - Switzerland Website : www.isan.org - Tel.: +41 22 545 10 00 - email: [email protected] James Bond’s Films Actor as Year Original Title Director ISAN James Bond Ken Hughes, John Huston, Joseph 1967 Casino Royale McGrath, Robert David Niven 0000-0000-1C49-0000-4-0000-0000-P Parrish, Val Guest, Richard Talmadge On Her Majesty's Secret 1969 Service Peter R.