Newsletter No 18 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliografia Cartilor in Curs De Aparitie

BIBLIOTECA NAŢIONALĂ A ROMÂNIEI CENTRUL NAŢIONAL CIP BIBLIOGRAFIA CĂRŢILOR ÎN CURS DE APARIŢIE CIP Anul XVII, nr. 10 octombrie 2014 Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României Bucureşti 2014 Biblioteca Naţională a României Centrul Naţional ISBN-ISSN-CIP Bd. Unirii, nr. 22, sector 3 Bucureşti, cod 030833 Tel.: 021/311.26.35 Fax: 021/312.49.90 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.bibnat.ro ISSN = 2284 - 8401 ISSN-L = 1453 - 8008 Redactor responsabil: Nicoleta Corpaci Notă: Descrierile CIP sunt realizate exclusiv pe baza informaţiilor furnizate de către editori. Centrul Naţional CIP nu-şi asumă responsabilitatea pentru modificările ulterioare redactării descrierilor CIP şi a numărului de faţă. © 2014 Toate drepturile sunt rezervate Editurii Bibliotecii Naţionale a României. Nicio parte din această lucrare nu poate fi reprodusă sub nicio formă, fără acordul prealabil, în scris, al redacţiei. 4 BIBLIOGRAFIA CĂRŢILOR ÎN CURS DE APARIŢIE CUPRINS 0 GENERALITĂŢI...............................................................................................8 004 Calculatoare. Prelucrarea datelor...............................................................9 008 Civilizaţie. Cultură...................................................................................15 01 Bibliografii. Cataloage...............................................................................19 05 Reviste cu caracter general ........................................................................19 06 Organizaţii. Asociaţii. Congrese. Expoziţii ...............................................19 -

New Pilgrimage Destination in Romania-The Tomb of Father Arsenie Boca at Prislop Monastery

“Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University Knowledge Horizons - Economics Volume 7, No. 3, pp. 151–153 P-ISSN: 2069-0932, E-ISSN: 2066-1061 © 2015 Pro Universitaria www.orizonturi.ucdc.ro NEW PILGRIMAGE DESTINATION IN ROMANIA-THE TOMB OF FATHER ARSENIE BOCA AT PRISLOP MONASTERY Mihaela Simona APOSTOL1, Adriana Anca CRISTEA2 , Tatiana Corina DOSESCU3 1“Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University, Faculty of Political Science Communication and Public Relations, Bucharest, Romania, E-mail: [email protected] 2“Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University, Faculty of Tourism and Commercial Management, Bucharest, Romania, E-mail: [email protected] 3“Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University, Faculty of Tourism and Commercial Management, Bucharest, Romania, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The emergence of new pilgrimage destinations enriches the cultural heritage of a country and sets Key words: in motion the economic growth locally, regionally and nationally. One of the best known pilgrimage Religious destinations in Romania is the tomb of Father Arsenie Boca located in Prislop. The information communication, religious provided by the media shows us that the number of pilgrims who come to Prislop is annually tourism , pilgrimage , growing. The possible canonization of Father Arsenie Boca and implicitly the official recognition of marketing this pilgrimage destination will have multiple implications in terms of culture and religion, but JEL Codes: especially economically. The development of infrastructure to support the development of tourism flows in the area, involves the development of a medium and long term strategy regionally and L 82, L83, M 31, locally. Tourism development will have a significant economic and image impact on the area M 37 Z 12 Introduction increases as the distance between the known world The pilgrimage is considered a powerful pastoral and the unknown world is greater. -

Arsenie Boca

-ARSENIE BOCA- Este considerat de mulţi credincioşi drept „ultimul sfânt al românilor“. Duhovnicul Arsenie Boca şi-a dus viaţa printre fapte considerate miracole de cei care le-au văzut şi vorbe cu tâlc, balansându-se între renumele profetic şi durerile simţite în temniţele comuniste. „Într-o zi, oamenii i s-au plâns: «Părinte, nu mai avem nisip de construcţie, ce ne facem? Numa dacă s-ar abate râul ăsta din loc, am mai putea găsi ceva nisip...». Părintele s-a dus în deal, pe apă, la vreo douăzeci de metri, şi s-a lăsat în genunchi. A făcut rugăciunea câteva ore. Şi, vă jur!, asta am văzut-o cu ochii mei, spre seară, apa a intrat în pământ şi a ieşit puţin mai încolo, lăsând la suprafaţă un nisip fin, strălucitor ca argintul. Muncitorii s-au închinat cu toţii, speriaţi, nevenindu-le să-şi creadă ochilor. «Rugaţi-vă, postiţi şi veţi putea şi voi!», le- a spus tuturor.“ Astfel de istorii, precum cea spusă de muncitorii care lucraseră la refacerea mănăstirii din localitate, puteau fi auzite, la Prislop, pe 28 noiembrie 1989. Atunci, toţi cei prezenţi acolo, proveniţi din toate zonele ţării, înfriguraţi de la vremea de afară şi extenuaţi de lipsurile unui regim politic ce mai avea de supravieţuit mai puţin de o lună, participau la ceva mai mult decât o înmormântare. Senzaţia era că România a pierdut un sfânt, o persoană în relaţie directă cu divinul, un făcător de minuni. Din sicriu, trupul lui Arsenie Boca trăda perioadele lungi de interogatorii, anchete şi întemniţări, al căror subiect fusese încă din anii 1950. -

The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala As a Runaway from the Secret Police and As a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania

The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala as a Runaway from the Secret Police and as a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania Cristina Plamadeala A Thesis in The Department of Theological Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Theological Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2015 © Cristina Plamadeala, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Cristina Plamadeala Entitled: The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala as a Runaway from the Secret Police and as a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Theological Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: __________________________________Chair Chair’s name __________________________________Examiner Examiner’s name __________________________________Examiner Examiner’s name __________________________________Supervisor Supervisor’s name Approved by_______________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______2015 _______________________________________________________ Dean of Faculty ii ABSTRACT The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala as a Runaway from the Secret Police and as a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania Cristina Plamadeala The present work discusses the life of the Romanian theologian Antonie Plamadeala (1926-2005) in the1940s-1950s. More specifically, it tells the story of his refuge from Bessarabia to Romania, of his run from Romania’s secret police (Securitate) and of his years of incarceration as a political prisoner for alleged ties to the Legionary Movement, known for its Fascist, paramilitary and anti-Semitic activity and rhetoric. -

A Romanian Narrative

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series IVA. Central and Eastern European Philosophical Studies, Volume 48 Series VIII. Christian Philosophical Studies, Volume 7 General Editor George F. McLean Faith and Secularization: A Romanian Narrative Romanian Philosophical Studies, IX Christian Philosophical Studies, VII Edited by Wilhelm Dancă The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2014 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Faith and secularation : a Romanian narrative / edited by Wilhelm Danca. pages cm. -- (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series IVA, Central and Eastern European philosophical studies ; Volume 48) (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series VIII, Christian philosophical studies ; Volume 7) (Romanian philosophical studies ; 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Romania--Church history--20th century--Congresses. 2. Secularization-- Romania--Congresses. 3. Christianity and culture--Romania--Congresses. 4. Catholic Church--Romania--Congresses. 5. Biserica Ortodoxa Romania-- Congresses. 6. Orthodox Eastern Church--Relations--Catholic Church-- Congresses. 7. Catholic Church--Relations--Orthodox Eastern Church-- Congresses. I. Danca, Wilhelm, 1959-editor of compilation. BR926.3.F35 2014 2014015096 274.98'082--dc23 CIP ISBN 978-1-56518-292-9 (pbk.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Wilhelm Dancă (University of Bucharest) Part I. Disjunctions between Catholic Church and People within the Romanian Orthodox Context Chapter I: “Wellness” in Religion, a Way of Emptying Churches? 11 Wilhelm Tauwinkl (University of Bucharest) Chapter II: Contradictory Sign of What is Missing: 25 A Narrative of Romanian Postcommunist Religiosity Violeta Barbu (University of Bucharest) Chapter III: Coming Back to Religion. -

On the Pilgrimage Pattern Related to Dumitru Staniloae and Arsenie Boca

ON THE PILGRIMAGE PATTERN RELATED TO DUMITRU STANILOAE AND ARSENIE BOCA. PRISLOP MONASTERY (e-)SITE. DOES SCIENCE-RELIGION-PHYLOSOPHY-ART-MANAGEMENT RELATION MATTER? Nicolae Bulz Associate Professor – National Defence College, Romania Honorary Researcher – Institute of World Economy / NERI/ Romanian Academy Research Associate External - Center for Strategic Economic Studies, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia President of the Interdisciplinary Research Group / Romanian Academy structures Dedicated to: Dumitru Staniloae (1903 –1993) - a great Romanian theologian/Dogmatic, professor, writer, philosopher Arsenie Boca (1910–1989) - a founder of non-canonic Orthodox Church painting and one of the resistive- Priests-monks to the injustice in the communist period in Romania Abstract: This dedicated study comprises the (re)presentation of three levels related to extraordinary topos: (1) on Hateg County; (2) on Prislop Monastery, and the pilgrimage mostly at the Priest Arsenie Boca’s simple tomb; (3) on the dyadic entity {Priest-monk Arsenie Boca – Priest and professor/academician Dumitru Staniloae}. There are some radial consequences to these three levels related to extraordinary topos: (4) on a relation SCIENCE-RELIGION-ART ON SYSTEMIC THINKING – as it would be elicited through an other extraordinary pilgrimage case at the Church Draganescu (near Bucharest); (5) an affirmation on the dyadic entity {Priest-monk Arsenie Boca – Priest and professor/academician Dumitru Staniloae} and the Aristotelianism; (6) on the relation SCIENCE-RELIGION-PHYLOSOPHY-ART-MANAGEMENT ON SYSTEMIC THINKING / on an introductory comprehension on: "I" and "you" - the first and the second persons: scientist, theologician (toward illuminated priest), philosopher, artist, manager, human being in the widest sense / on an introductory analysis of an "I" and "you" matrix / on an invariant within the matrix-distance between "I" and "you"; (7) on the systemic dynamics related to Tourism / e-Tourism. -

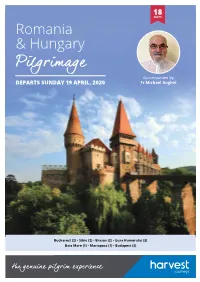

Pilgrimage Accompanied by DEPARTS SUNDAY 19 APRIL, 2020 Fr Michael Anghel

18 DAYS Romania & Hungary Pilgrimage Accompanied by DEPARTS SUNDAY 19 APRIL, 2020 Fr Michael Anghel Bucharest (2) • Sibiu (2) • Brasov (2) • Gura Humorului (3) Baia Mare (1) • Mariapocs (1) • Budapest (3) the genuine pilgrim experience Meal Code in the Middle Ages for its fortification our time here with a visit to Peles Castle, built B: Breakfast L: Lunch D: Dinner system considered then to be the largest in the late 19th century in the typical Bavarian in Transylvania. Admire the Large Square neo-Gothic style. After Mass in the Sacred DAY 1: SUNDAY 19 APRIL 2020 – DEPART with the city roofs of “eyes that follow you,” Heart Cathedral, we reboard our coach. FOR EUROPE the Little Square with the Bridge of Lies and the impressive 14th century Gothic style Optional: We journey north to Bran for an DAY 2: MONDAY 20 APRIL – ARRIVE Evangelical Church. Before checking in to our optional visit to the site known as ‘Dracula’s BUCHAREST (D) hotel we will celebrate Mass at the Catholic Castle’, one of the most picturesque in On arrival at Bucharest airport we will be Cathedral dedicated to the Holy Trinity. Romania, dating back to the 13th century and once the residence of the Royalty of the met and board our coach. We catch our Sibiu overnight first glimpses of this interesting city with a Kingdom of Romania. panoramic tour. Admire the wide boulevards, DAY 5: THURSDAY 23 APRIL – SILVASUL DE We return to Brasov in time for dinner. the glorious Belle Epoque buildings, the SUS & HUNEDOARA (BD) Brasov overnight Triumphal Arch, Roman Athenaeum, After breakfast this morning we travel by Revolution Square and University Square en coach to Silvasul de Sus to visit the Prislop DAY 8: SUNDAY 26 APRIL – BRASOV TO route to our hotel for check-in. -

Father André Scrima – a New Kind of Fool for Christ Marius

M!"#$% V!%#&'!($* !e complex and often puzzling personality of Father André Scrima was misapprehended for a long time. !is article discusses the reasons for such a misapprehension and o"ers some possible explanations for his paradoxical behaviour. An overview of the reception of Father Scrima’s life and works shows a dynamic at work that can only generate optimism. His participation in the Burning Bush group at the Antim monastery in Bucharest was one of the most important formative experiences, where a wide cultural and scienti#c perspective was fused with an in- depth religious experience. Father Scrima may be better understood if we consider him the #rst of a new kind of fools for Christ, a kind that is well-equipped to face the challenges of tomorrow. Keywords: André Scrima, Daniil Sandu Tudor, !e Burning Bush, foolishness for Christ, hesychasm He was a man that would experience the enthusiasm of a child when a new decimal of a universal constant was discovered. He used to tame an unbro- ken sacred text in a generous hermeneutics by o!ering it the "re of certain astrophysical theories and blending them with the phenomenology of the opening one’s heart in a hesychastic manner. Could this be the reason why the impressive erudition of Father André Scrima is still hard to accept and to understand in the Orthodox ecclesiastical environment? Our hypothesis that will be dealt with in the current paper is that all the things mentioned above are not enough to explain his misapprehension: most likely, Father André Scrima was the "rst person belonging to a new kind of fool for Christ. -

Principesa Ileana a României Şi Părintele Arsenie Boca Princess Ileana of Romania and Father Arsenie Boca

MUZEUL NA ŢIONA L Voi. XXVI 2014 PRINCIPESA ILEANA A ROMÂNIEI ŞI PĂRINTELE ARSENIE BOCA PRINCESS ILEANA OF ROMANIA AND FATHER ARSENIE BOCA Nicoleta Petcu· Abstract In the 1940s, Princess Ileana of Romania, Archduchess of Austria, met Father Arsenie Boca, the Abbot of the Brancoveanu Monastery from Sambata de Sus, who was considered by his parishioners a saint even prior to his death. The work presents information regarding the relationship of Princess Ileana, future abbess herself, with Father Arsenie Boca, whom she met either at the Brancoveanu Monastery from Sambata de Sus, on the occasion of the re consecration of Sfanta Tr eime Church (Holy Trinity Church) fromBrasov- Tocile, or as a result ofthe Princess's invitations to Bran Castle and to her home located in Baneasa Neighborhood in Bucharest. Some of the information presented in this work has never been published before - for example, Father Arsenie Boca's note fr om August 315\ 1946 in the journal of the Bran camp organized for the girl student refugees fromBes sarabia. Keywords: Princess Ileana of Romania, Father Arsenie Boca, Bran Castle, Brancoveanu Monastery from Sambata de Sus. Ideea acestei lucrări a apărut odată cu prilejul întâlnirii din 11 iulie 2009 pe care am avut-o în satul Hăţăgel, comuna Densuş, judeţul Hunedoara, cu Preasfinţitul părinte Daniil Stoenescu, episcop-locţiitor al Episcopiei Daciei Felix, ucenic al părintelui Arsenie Boca, care mi-a relatat că părintele Arsenie a fo st ca o lumină în viaţa principesei Ileana a României. În procesul-verbal de interogatoriu al Securităţii regimului comunist, din 11 octombrie 1955, profesorul Nichifor Crainic, care a suferit mulţi ani de puşcărie la Aiud, mărturisea că părintele Arsenie Boca "este un călugăr de o reală valoare spirituală, care s-a tăcut foarte cunoscut în părţile ardelene, prin viaţa lui personală riguros morală, prin predicile lui de o mare putere de influenţă asupra sufletelor şi printr-o pătrunzătoare artă de a lămuri stările de psihologie religioasă şi de a da • Muzeograf, Muzeul Naţional Bran. -

Arsenie Boca 1 Arsenie Boca

Arsenie Boca 1 Arsenie Boca AVERTISMENT: articolul nu a putut fi reprodus în întregime — va rezulta text plan. Posibilele cauze ale problemei sunt: (a) un defect al software-ului PDF-Writer (b) o marcare problematică a codului MediaWiki (c) un tabel prea lat Părintele Arsenie Boca la Mânăstirea Sâmbăta de SusAcest articol din seria Creștinism se referă la Creștinism ortodoxOrtodoxie.Sfânta TreimeDumnezeuIisus HristosSfântul DuhBibliaMărturisirea de credință (crezul)Simbolul niceno-constantinopolitanSimboluriCruceMonograma Lui Iisus HristosPeștele (simbol)Păstorul (simbol)Pomul viețiiVița de vie (simbol)SfințiIoan BotezătorulAndrei (apostol)Petru (apostol)Sfântul mucenic LaodichieArsenie cel MareEpifanie de SalaminaSfântul noul mucenic Arghiros TesaloniceanulSfântul noul mucenic Ioan ValahulBiografiiDumitru StăniloaeArsenie BocaArsenie PapaciocConstantin GaleriuIlie CleopaNicolae NeagaIlarion ArgatuChristos YannarasNicolae SteinhardtBiserica Ortodoxă RomânăPatriarhii Bisericii Ortodoxe RomâneMitropoliți româniSfinții militari ai Bisericii Ortodoxe RomâneCultură și artăScriitori creștini ortodocșiLăcașurile de cult ale Bisericii Ortodoxe RomâneArsenie Boca (n. 29 septembrie 1910, Vața de Sus, HunedoaraVața de Sus, România - d. 28 noiembrie 1989, Mănăstirea Sinaia, Județul PrahovaProhova), părinte ieromonah, teolog și artist plastic (muralist) român, a fost stareț la Mănăstirea Sâmbăta de SusMănăstirea Brâncoveanu de la Sâmbata de Sus și apoi la Mănăstirea Prislop, unde datorită personalității sale veneau mii și mii de credincioși, fapt pentru -

The Historical and Current State of Romanian-Russian Relations

DEFENCE, FOREIGN POLICY AND SECURITY THE HISTORICAL AND CURRENT STATE OF ROMANIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS TOMASZ PORĘBA • STANISŁAW GÓRKA • ARMAND GOSU • OCTAVIAN MANEA • CORINA REBEGEA • ZUZANNA CHORABIK www.europeanreform.org @europeanreform Established by Margaret Thatcher, New Direction is Europe’s leading free market political foundation & publisher with offices in Brussels, London, Rome & Warsaw. New Direction is registered in Belgium as a not-for-profit organisation and is partly funded by the European Parliament. REGISTERED OFFICE: Rue du Trône, 4, 1000 Brussels, Belgium. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Naweed Khan. www.europeanreform.org @europeanreform The European Parliament and New Direction assume no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this publication. Sole liability rests with the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL by Tomasz Poręba 7 1 RUSSIAN INFLUENCE IN ROMANIA Conversation with Stanisław Górka, PhD 8 2 ROMANIA IN A CHANGING GLOBAL CONTEXT: 20 RELATIONS WITH THE US AND RUSSIA by Armand Gosu & Octavian Manea 3 RUSSIAN INFLUENCE IN ROMANIA by Corina Rebegea 30 4 IS ROMANIA A ‘NATURAL’ ENEMY OF RUSSIA? by Zuzanna Chorabik 54 APPENDIX 62 New Direction - The Foundation for European Reform www.europeanreform.org @europeanreform EDITORIAL Tomasz Piotr Poręba Tomasz Poręba is a Member of the European Parliament and President of New Direction – The Foundation for European Reform. THE HISTORICAL AND ussia has been a significant neighbour and its attempts to undermine European unity through regional actor for Romania since the end of energy interests, political funding and media (dis) R the Communist regime in 1989. Russia has information. CURRENT STATE OF been perceived in Romania as a threat for much of its history. -

Positions Towards a Multiple Knowledge of God

POSITIONS TOWARDS A MULTIPLE KNOWLEDGE OF GOD: INTERPRETING THE RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE IN AN ORTHODOX CHURCH By Carmen Maria Manea Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisors: Prof. Vlad Naumescu Prof. Marianne Saghy CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2015 ABSTRACT Current debates on religious knowledge could be characterized, with the risk of essentializing their methods and outcomes, as divided between a classical path opened by Weber and Durkheim and a modern tendency to pull apart the chains of 19 and early 20th century scholarly traditions by contesting their methodological foundations and/or religious and ethical standpoints. The ethical, political and belief foundations of the “intellectualist” British anthropology of religion had a strong impact on the subsequent development of the social studies on religion and kept a breach between anthropology and theology. Only with the writings of Evans-Pritchard, Mary Douglas and the efforts of Victor and Edith Turner to bring Christian beliefs, experiences and emotions to the attention of anthropology beside phenomenological explanations, did anthropology make a significant step in getting closer to theological studies. These will all be contrasted with my own positionality in what concerns the knowledge about God and the subsequent reading of the experiences, religious practices and language used by the members of the Romanian monastery (Budapest) to show their own understanding of God as He is, as He manifests His presence or as He makes himself knowable to the believer. Thus, this work could be marked as an experiment, albeit all its faults, in an ethnography of spirituality and in self-reflexivity.