SIKKIM a Short Political History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INSET Within Bhutan, 1996-1998 and the INSET Framework Within Bhutan, 2000 – 2004/6

INSET within Bhutan, 1996-1998 and the INSET Framework within Bhutan, 2000 – 2004/6. by DJ Laird TW Maxwell University of New England, Australia Wangpo Tenzin CAPSS, Education Division, RGoB & Sangay Jamtsho National Institute of Education, Bhutan INSET Project Report _________________________________________________________ i Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – INSET PROJECT 1996-1998 .................................................................. 1 Reconceptualisation of INSET ............................................................................................. 1 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 7 BACKGROUND TO THE INSET PROJECT ........................................................................................ 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Project Brief.......................................................................................................................... 8 Rationale for Project Involvement ........................................................................................ 8 Project Questions .................................................................................................................. 9 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK .......................................................................................................... 11 Growth of School Systems in Developing Countries -

The Bhutan MONTHLY R E P O R T E R

The Bhutan MONTHLY R E P O R T E R Volume IV No 38, December 2007 www.bhutannewsservice.com Pages 4, Rs 4 Jubilee of Nehru’s visit Agreement has reached between Bhutan and India authorities to jointly celebrate Bhutan, 2004. use of weapons and explo- Pragathisel Sanskriti Pariwar, Bhutan News Service the golden jubilee of Jawaharlal The government mouth sives. Srijana Sanskriti Pariwar and Kathmandu, September Nehru’s first visit to Bhutan piece Kuensel quoted the court The court said, two Class Saipatri Sanskriti Pariwar which next year. officials saying that using a re- XII students, had connected are formed to strengthen the India’s first Prime Minister vis- The Samtse district court ligious façade called the Srijana with the Bhutanese in exile to communist ideology in the ited Bhutan in September 1958 has given its verdict in favor Sanskrit Sangathan, the group attend briefing sessions on country. that paved the beginning of a of sending 30 southern had held several meetings to Political and Ideology Train- Police claimed they recov- new relationship between Bhutanese to jail for five to discuss Maoist ideology and to ing conducted by the cadres ered detonators and other ma- these countries. The visit nine years on charges of in- collect money and food grain of the CPB. The government terials used for making impro- opened up the Bhutan to out- volving in seditious activities. for the Communist Party of also claimed that the Nepal vised explosive devices, mem- side world, ended its century The court after five Bhutan. People who attended Maoist and Communist Party bership forms of the Party and long isolation and delved the months long proceedings the meetings were made to fill of Nepal, Bhutan Peoples’ All Bhutan Revolutionary Stu- path to economic development. -

7014414.PDF (8.788Mb)

70-1 4 ,UlU BELFIGLIO, Valentine John, 1934- THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF INDIA WITH BHUTAN, . SIKKIM AND NEPAL BETWEEN 1947-1967: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE STUDY OF BIG POWER-SMALL POWER RELATIONS. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1970 Political Science, international law and relations University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © VALENTINE JOHN BELFIGLIO 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF INDIA WITH BHUTAN, SIKKIM AND NEPAL BETWEEN 1947-196?: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE STUDY OF BIG POWER-SMALL POWER RELATIONS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ,1^ VALENTINE J. BELFIGLIO Norman, Oklahoma 1970 THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF INDIA WITH BHUTAN, SIKKIM AND NEPAL BETWEEN 1947-196?: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE STUDY OF BIG POWER-SMALL POWER RELATIONS APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PREFACE The following International Relations study is an effort to provide a new classification tool for the examination of big power-small power relationships. The purpose of the study is to provide definitive categories which may be used in the examination of relationships between nations of varying political power. The rela tionships of India with Bhutan, Sikkim, and Nepal were selected for these reasons. Three different types of relationships each of a distinct and unique nature are evident. Indian- Sikkimese relations provide a situation in which the large power (India) controls the defenses, foreign rela tions and internal affairs of the small power. Indian- Bhutanese relations demonstrates a situation in which the larger power controls the foreign relations of the smaller power, but management over internal affairs and defenses remains in the hands of the smaller nation. -

PART-I SUMMARY of REVIEW REPORT of AAR2017 the Royal

PART-I SUMMARY OF REVIEW REPORT OF AAR2017 The Royal Audit Authority had submitted the Annual Audit Report 2017 to the 11th Session of the Second Parliament in June 2018. The Review Report had total significant unresolved irregularities of Nu.4,309.765 million consisting of Nu.238.484 million against budgetary agencies; Nu.168.629million against Non- Budgetary Agencies and Nu.3,974.652millions against Hydro Power Projects as of June 2018. The RAA had conducted numerous follow-ups at various levels in line with Chapter 6 Section 119 to 123 of the Audit Act of Bhutan 2018 and subsequently, irregularities amounting to Nu.29.057 million (12.184%)for Budgetary Agencies, Nu.14.046 million (8.330%) for Non-budgetary Agencies and Nu.23.141 (0.582 %)for Hydro Power Projects were resolved as on 30/09/2018 as shown in Table below. TABLE showing agency wise irregularitie resolved and balances as on30/09/2018 Sl. Agencies Unresolved Irregularitie Balance Percentage No. irregularities s resolved irregularities of reported in as on as on irregularities June 2018 30/09/201 30/09/2018 resolved as (Nu.in 8 (Nu.in (Nu.in Million) on Million) Million) 30/09/2018 1 Ministries 115.212 14.312 100.900 12.422 2 Dzongkhags 38.137 2.606 35.531 6.833 3 Gewogs 12.382 1.483 10.899 11.977 4 Autonomous 72.753 10.656 62.097 14.647 Agencies Total Budgetary 238.484 29.057 209.427 12.184 Agencies-A5 Corporations (1to 4) 148.096 13.633 134.463 9.206 6 Non 20.533 0.413 20.120 2.011 Govermental Organization s Total Non- 168.629 14.046 154.583 8.330 Budgetary7 Hydropower 3,974.652 23.141 3,951.511 0.582 Projects Total Hydropower 3,974.652 23.141 3,951.511 0.582 Projects-CGrand Total(8) 4,381.765 66.244 4,315.521 1.512 (A+B+C) As transpired from table above, out of the total unresolved irregularities of Nu.4,381.765million remaining unresolved as of June 2018, irregularties amounting toNu.66.244 million (1.51%)were resolved leaving a balance of Nu.4,315.521 (98.49%)million as on 30/09/2018. -

State of Research and Institutional Linkages

STATE OF RESEARCH AND INSTITUTIONAL LINKAGES Royal University of Bhutan 2018-2019 Royal University of Bhutan, Office of the Vice Chancellor, Lower Motithang, Thimphu, Bhutan, P.O. Box. 708 Tel: +975 2 336454 Fax: +975 2 336453 www.rub.edu.bt Printed at Bhutan Printing Solutions (www.prints.bt) STATE OF RESEARCH AND INSTITUTIONAL LINKAGES Royal University of Bhutan 2018-2019 Department of Research and External Relations Office of the Vice Chancellor Royal University of Bhutan Lower Motithang P.O. Box. 708 Thimphu: Bhutan Copyright © 2020 Department of Research and External Relations (DRER), Royal University of Bhutan. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted, or disseminated, in any form, or by any means with due acknowledgement. State of Research and Institutional Linkages 2018-2019 Preface This annual report of the financial year 2018-2019 is the 1st year document of the 12th Five Year Plan (12FYP 2018-2023). Two consecutive annual reports of the “State of Research and Institutional Linkages of the Royal University of Bhutan” were published during the 4th and 5th year of the 11th Five Year Plan 2013-2018. This report is expected to serve as the baseline in evaluating research, innovation and external collaborations services rendered by the Royal University of Bhutan (RUB) at the end of the 12FYP period. The structure of the report is therefore aligned to the specific objectives of the RUB Strategic Plan (2018-2030) wherein the Department of Research and External Relations (DRER) has entered into the Annual Performance Agreement (APA) by establishing clarity and consensus of annual priorities in making the department accountable and providing a fair evaluation of the services during the reporting year. -

EMBASSY of INDIA, THIMPHU (Education Section) Registration No Name Bhutanese Citizenship ID Card No. 20200003 Mr.Siddharth Pradh

EMBASSY OF INDIA, THIMPHU (Education Section) Registration Name Bhutanese Citizenship No ID Card No. 20200003 Mr.Siddharth Pradhan 11803002975 20200004 Ms.Tenzin Lhaden 11410008890 20200005 Ms.Pema yangzom 11505003030 20200008 Ms.Kinley Zangmo 11407000628 20200011 Mr.KARMA LEKSHAY WANGPO 10304000053 20200013 Ms.PemaTshomo 12007003074 20200014 Mr.KARMA SAMTEN DORJI 11407000600 20200019 Ms.Karma Dema 10202000438 20200024 Ms.Sangay Choden 10709005302 20200029 Mr.Karma wangchuk 10101004120 20200030 Ms.Dechen Pemo 11513006222 20200031 Ms.Jigme Wangmo 11512005448 20200033 Ms.Anisha Ghalley 11303000188 20200034 Ms.Kinley Choden 10904002963 20200035 Mr.Tshering zam 10202000439 20200037 Ms.Kezang Choden 11514001637 20200038 Ms.DIPIKA POKWAL 11804000702 20200039 Ms.Sonam Tshomo 10807001153 20200040 Ms.Kinley Om 10202000437 20200041 Ms.Sonam chokey 11705000500 20200042 Mr.Yeshi Tshering 11101000872 20200043 Ms.Legzin Wangmo 11405000748 20200044 Ms.Priyarna Gurung 11110000073 20200045 Ms.Pritam Ghalley 11204002078 20200046 Ms.Kamala Devi Rizal 11310000604 20200047 Mr.Reshi Prasad Pokhrel 11109001849 20200048 Mr.NIKITA RAI 11211001762 20200049 Mr.Sonam Tobgay 10807002319 20200050 Mr.Dhan Kumar Adhikari 20200005102 20200051 Mr.Ngawang Dorji 10808001072 20200052 Ms.Yangchen Dema 11106003859 20200053 Mrs.Tshewang Lhamo 11303003231 20200054 Ms.Gaygye Nima Tamang 10201000093 20200055 Mr.Kinley Rabgay 11704003371 20200056 Mr.Shajan Gurung 11201000367 20200057 Mr.Chimi Tenzin Wangchuk 11107001527 20200058 Mrs.Choney Zangmo 11312001321 20200059 Mrs.Sonam -

SL No. Name CID E-Mail 1 Singye Dorji 11512002019

First Cohort 23rd August 2021 SL No. Name CID e-mail 1 Singye Dorji 11512002019 [email protected] 2 Dorji Choda 12007001136 [email protected] 3 Chimi Dorji 10905002385 [email protected] 4 Pema Tshewang 11312002609 [email protected] 5 Changala 11704002459 [email protected] 6 Karma tharchen 11703001499 [email protected] 7 Tshering Chophel 10101005413 [email protected] 8 Mumta suberi 11805002849 [email protected] 9 Sonam Dendup 1904000569 [email protected] 10 Pema Tshewang 1.13123E+11 [email protected] 11 Anjana Suberi 11805000922 [email protected] 12 kelzang dawa 10714002479 [email protected] 13 Dorji Om 11909000058 [email protected] 14 kinzang wangchuk 10702000772 [email protected] 15 Nar Bdr Dhital 11311000384 [email protected] 16 sonam Rabten 11810001293 [email protected] 17 Kinga Tshering 10802001933 [email protected] 18 Cheki Dorji 10905003045 [email protected] 19 Karma Gyeltshen 10809000149 [email protected] 20 Nima Dorji 11506001259 [email protected] 21 Rinzin Dema 11005003189 22 Pema Dorji 11107003862 [email protected] 23 Tshering Choden 11508002443 [email protected] 24 Sonam Dorji 11102006714 sdconst2021@gmail 25 Thinley choden 11410005125 [email protected] 26 Indira Maya Ghalley 11215000945 [email protected] 27 kinley Tshering 11915000245 [email protected] 28 ugyen wangmo 10805000839 [email protected] 29 Tenzin Phuentsho 11807000957 [email protected] 30 Pema Dechen -

Newsletter 37 (Summer 2007)

THE BHUTAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Number 37 President: Lord Wilson of Tillyorn, KT GCMG FRSE Summer 2007 Monday 17th September, 2007 The 15th Annual Dinner of the Bhutan Society Recent Events in Bhutan 26th October, 2007 An informal talk by Michael Rutland Application form enclosed. Please also see p. 2 Michael Rutland, our Hon. Secretary and Bhutan s Lyonpo Hon. Consul to the UK, will give his very popular annual roundup of events that have taken place in Bhutan over the past 12 months. This year has been Dawa particularly interesting and challenging with emerging political system causing some confusion, and the Tsering painfully slow appearance of political parties... The talk will be illustrated with slides and the intention is to provide plenty of opportunity for the 1935-2007 audience to ask questions about any aspects of modern Bhutan which interest them. Michael, who lives in Bhutan for much of each year, is particularly well placed to discuss the changes and Dasho developments taking place in the country, perhaps spiced with the odd bit of gossip! Lhendup Monday 17th September, 2007 6:30pm for 7:00pm Dorji The Oriental Club Stratford Place, London W1C 1ES Drinks available before the lecture 1935-2007 PLEASE NOTE: Oriental Club rules require gentlemen to wear jacket and tie, and do not allow the wearing of jeans! For obituaries see page 5 The Society s website is at www.bhutansociety.org and carries information about the Society, news and events, an archive of Newsletters and a selection of interesting Bhutan-related links. The Bhutan Society of the UK: Unit 23, 19-21 Crawford Street, London W1H 1PJ E-mail: [email protected] For membership enquiries please see the Society s website, or contact the Membership Secretary, Mrs. -

Indiens Unabhängigkeit Und Ihre Auswirkungen Auf Sikkim, Nepal

Sonderteil"50 Jahre Unabhängigkeit" Indiens Unabhängigkeitund ihre Auswirkungen auf Sikkim, Nepalund Bhutan von Karl-Heinz Krämer Die HimalayastaatenNepal, Sikkim und Bhutan gehörtenzu den Randbereichendes britischen Kolo- nialeinflusses.Markant ist. daß Nepal,das am frühestenin die britischenHandelsambitionen einbezo- gen wurde, weil man sich über Kathmandueinen Zugangzu Innerasienzu erschließenhoffte, bis zu- letzt formell seine Unabhängigkeitbewahren konnte. Sikkim wurde Mitte des 19. Jahrhundertszu ei- nem britischen Protektorat und verlor zeitweise weitgehend seine politische Eigenständigkeit.Etwas bessergestellt war Bhutan, das zu Beginndes 20. Jahrhundertsbritischen Protektoratsstatus erhielt, als mit britischer Billigungeine Monarchie das traditionelleStaatssystem des Landes abgelöst hatte. Nach der indischen Unabhängigkeit im an der Südflanke des hohen Himalaya tere Entwicklung war daräber hin4us gs- Jahre L947 waren alle drei Himalaya- konnten sie sichjedoch einem mehr oder prägt von indischen Sicherheitsinteressen staaten bemäht, ihre Souveränität und weniger süarken Einfluß lndiens, über und internen politischen Tendenzen der Unabhängigkeit zu bewahren bav. wie- dessen Territorium allein ein Seezugang drei Staaten. derherzustellen. Angesichts ihrer Lage möglich war, nicht entziehen. Die wei- Interessant ist, daß die Himalayastaa- ten unabhängig von ihrem jeweils vor- gegebenen kulturellen Hintergrund alle- samt Parallelen aufiveisen, und zwar sowohl hinsichtlich ihrer politischen und gasellschaftlichen Strukturen als auch rn bezug auf die Entwicklung von Demo- kratie und ziviler Gesellschaft. Daber zeigen sie sich heute auf unterschiedli- chen Stufen dieser Entwicklung. Nepal, Sikkim und Bhutan liegen in Bereich der BegegnungszoneSüd- und nsildk im Zentralasiens. Ihre Gesellschaften und Kulturen sind daher gemischt. Im hufc der Jahrhunderte sind Völker sowohl vom tibetischen Hochland als auch aut den indischen Ebenen zugewandert. Mr- litärische Expansion und andauerode Migration trugen zu einer weiteren Ver- größerung dieser Vielfalt bei. -

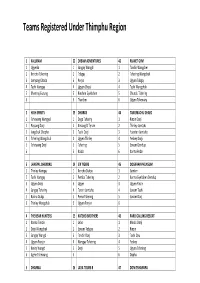

Teams Registered Under Thimphu Region

Teams Registered Under Thimphu Region 1 KALURAM 22 DREAM ADVENTURES 43 PLANET GYM 1 Ugyenla 1 Sangay Wangdi 1 Tandin Wangchen 2 Kencho Tshering 2 Tobgay 2 Tshering Wangchuk 3 Jamyang Choda 3 Penjor 3 Ugyen Tobgay 4 Tashi Namgay 4 Ugyen Choda 4 Tashi Wangchuk 5 Khemraj Gurung 5 Rinchen Gyeltshen 5 Chundu Tshering 6 6 Tharchen 6 Ugyen Tshewang 2 HIGH SPIRITS 23 DHOROS 44 TANGMACHU CHARO 1 Tshewang Namgyal 1 Dago Tshering 1 Rinzin Dorji 2 Passang Dorji 2 Kinzang D Tenzin 2 Thinley Jamtsho 3 Jangchuk Chophel 3 Tashi Dorji 3 Yoenten Jamtsho 4 Tshering Wangchuk 4 Ugyen Thinley 4 Yeshey Dorji 5 Tshewang Dorji 5 Tshering 5 Sonam Dendup 6 6 Kaido 6 Karma Peden 3 LHAGYAL DHENDRU 24 SIX TIGERS 45 DOGKHAR PHUNSUM 1 Thinley Namgay 1 Kencho Dukpa 1 Samten 2 Tashi Namgay 2 Pemba Tshering 2 Karma Gyeltshen Dendup 3 Ugyen Dorji 3 Ugyen 3 Ugyen Rinzin 4 Sangay Tshering 4 Tenzin Jamtsho 4 Sonam Tashi 5 Bokhu Dukpa 5 Pema Tshering 5 Sonam Dorji 6 Thinley Wangchuk 6 Ugyen Penjor 6 4 THE BEAR HUNTERS 25 KATSHO BROTHERS 46 PARO GALLING RESORT 1 Karma Tenzin 1 Lebo 1 Mindu Dorji 2 Dorji Wangchuk 2 Sonam Tobgay 2 Rinzin 3 Sangay Wangdi 3 Tandin Dorji 3 Tashi Daw 4 Ugyen Penjor 4 Namgay Tsheirng 4 Yeshey 5 Kinley Wangdi 5 Dorji 5 Ugyen Tsheirng 6 Jigme Tshewang 6 6 Dophu 5 DHARMA 26 LAYA TOURS B 47 DOM TSHANGPA 1 Karma 1 Dasho Lhendup Dorji 1 Chompa 2 Dawa Dukpa 2 Namgay Dorji 2 Tshering Tashi 3 Tshering Nidup 3 Ratu 3 Tshering Chophel 4 Ugyen Penjor 4 Sangay Khandu 4 Chador Namgey 5 Kaka 5 Sonam Tobgay 5 Mani Dorji 6 Dawa 6 Chador Wangdi 6 Ugyen 6 YANGCHEL GATSHEL 27 AA -YANG 48 THIMPHU UNITED 1 Thinley Wangdi 1 Jigme Dukpa 1 Karma Thinley 2 Tandin Dorji 2 Jigme Nidup 2 Kanjur 3 Gyem Tshering 3 Ata Yeshi 3 Sangay Dawa 4 Dophu 4 Pema Wangda 4 Phub Tshering 5 Tandin Wangchuk 5 Wangchuk 5 Kuenley Tenzin 6 6 Karma Dendup 6 Tsentop Sanagy 7 LUNGTA DE NGA 28 WANGTHANG 49 CHOKRA THAY 1 Sangay Phuntsho 1 Dorji Namgyal 1 Tshewang Thinley 2 Pema Dorji 2 Passang Tshering 2 Kunzang Namgyel 3 Jigme Dorji 3 Sonam Zangpo 3 Sherub Phuntsho 4 Singay Karmo 4 Capt. -

List of Construction Firms, Consultancy Firms, Architects Contributed for COVID-19

List of Construction firms, Consultancy firms, Architects contributed for COVID-19 Sl # CDB No Name Of Firm Name CID No Sex Dzongkhag Class Contribution Amount 1 1296 GYELTSHEN Construction Gyeltshen 10101005471 M Bumthang M 3,000.00 2 1432 SANGAY THINLEY Construction Sangay Thinley 10101001301 M Bumthang M 2,000.00 3 1950 NOLA Construction Nola 10101005441 M Bumthang S 7,777.00 4 2223 KARMA Construction Karma Jangchub 10102000686 M Bumthang S 555.00 5 2379 TSHERING Construction Private Limited Tshering Tobgay 10101001728 M Bumthang L 5,005.00 6 2403 UDEE Construction Ugyen Dorji 10101003886 M Bumthang M 2,000.00 7 3483 PHUNTSHOK GAKHIL Construction Tashi Dorji 10101005410 M Bumthang S 5,000.00 8 3902 YEARANG Construction Karma 12004003939 M Bumthang S 1,000.00 9 4087 DRUK PHUNTSHO KUENJUNG Construction Rinzin Namgyel 12008001828 M Bumthang S 1,234.00 10 4155 PHUNRABGYAL Construction Tenzin Choda 10101000578 M Bumthang L 7,777.00 11 4197 SONAM T. Construction Sonam Tshering 10101003878 M Bumthang M 2,000.00 12 4392 LAKSHOGANG Construction Sonam Wangchuk 10606001319 M Bumthang S 1,050.00 13 4654 DORJI YADRAK Construction Dorji Tshering 10101002509 M Bumthang S 700.00 14 4762 UGYEN CHAMKHAR Construction Ugyen Dorji 10101000046 M Bumthang S 3,015.00 15 5199 DEAZHE Construction Ugyen Lhendup 12006000985 M Bumthang S 1,000.00 16 5444 GYESELING Construction Pema Zangmo 10104001408 F Bumthang S 1,300.00 17 5823 PELING Construction Palden Singay 10109000987 M Bumthang S 1,500.00 18 5867 PEL JUANG Construction Thinley Dorji 10102002972 M Bumthang S 1,555.00 19 6533 U. -

Merit List of Registered Candidates for In-Country Rgob Scholarships To

Merit List of Registered Candidates for In-Country RGoB Scholarships to RTC for 2019 B.A. Sociology and Political Science (Min. 50% in English and 50% each in three best subjects including Dzongkha) Tie Breaker Application Merit Rank Merit Sex STUDIESMEDIA SCIENCE ENVIRONMENT DRIGLAM CHOEDJUK SUMTAG AGRICULTURE BUSINESS MATHEMATICS BIOLOGY STUDIESCOMPUTER PHYSICS CHEMISTRY DZONGKHA RIZHUNG DZONGKHA ENGLISH MATHS ECONOMICS GEOGRAPHY HISTORY LITERATURE IN ENGLISH ACCOUNTS COMMERCE NYENGAG Total Ranking Point % Average Number Index Number School Name CID Stream DZONGKHA Total Ranking Point + Dzongkha Total Marks Prem Tinsulanonda International 1 941_1902S00049 Sherab Dolma F 11405001037 SCIENCE 82 82 100 95 95 95 385.00 96.25 100 485 549.0 School UGYEN ACADEMY HIGHER 2 941_1902S01525 012180260070 Tshering Wangmo F 10501001499 SCIENCE 95 93 72 78 98 343.00 85.75 72 415 436.0 SECONDARY SCHOOL 3 941_1902S00331 012180060040 DAMPHU CENTRAL SCHOOL Sangay Nidup M 12001000816 SCIENCE 94 81 73 74 98 339.00 84.75 73 412 420.0 UGYEN ACADEMY HIGHER 4 941_1902S00759 012180260027 Dechen Namgay M 11411003111 SCIENCE 80 89 88 79 82 338.00 84.50 79 417 418.0 SECONDARY SCHOOL 5 941_1902S00989 012180070030 DRUKGYEL CENTRAL SCHOOL Tashi Phuntsho M 10805002512 SCIENCE 87 91 78 71 98 338.00 84.50 78 416 425.0 JIGME SHERUBLING CENTRAL 6 941_1902S00176 012180110032 Sonam Rinzin M 11602000450 SCIENCE 96 89 78 73 90 337.00 84.25 78 415 426.0 SCHOOL UGYEN ACADEMY HIGHER 7 941_1902S01971 012180260073 Dhan Raj Rai M 11302001375 SCIENCE 97 86 70 71 99 337.00 84.25 70