7014414.PDF (8.788Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lakes: the Mirrors of the Earth BALANCING ECOSYSTEM INTEGRITY and HUMAN WELLBEING

Lakes: the mirrors of the earth BALANCING ECOSYSTEM INTEGRITY AND HUMAN WELLBEING Proceedings of 15th world lake conference Lakes: The Mirrors of the Earth BALANCING ECOSYSTEM INTEGRITY AND HUMAN WELLBEING Proceedings of 15TH WORLD LAKE CONFERENCE Copyright © 2014 by Umbria Scientific Meeting Association (USMA2007) All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-88-96504-04-8 (print) ISBN: 978-88-96504-07-9 (online) Lakes: The Mirrors of the Earth BALANCING ECOSYSTEM INTEGRITY AND HUMAN WELLBEING Volume 2: Proceedings of the 15th World Lake Conference Edited by Chiara BISCARINI, Arnaldo PIERLEONI, Luigi NASELLI-FLORES Editorial office: Valentina ABETE (coordinator), Dordaneh AMIN, Yasue HAGIHARA ,Antonello LAMANNA , Adriano ROSSI Published by Science4Press Consorzio S.C.I.R.E. E (Scientific Consortium for the Industrial Research and Engineering) www.consorzioscire.it Printed in Italy Science4Press International Scientific Committee Chair Masahisa NAKAMURA (Shiga University) Vice Chair Walter RAST (Texas State University) Members Nikolai ALADIN (Russian Academy of Science) Sandra AZEVEDO (Brazil Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) Riccardo DE BERNARDI (EvK2-CNR) Salif DIOP (Cheikh Anta Diop University) Fausto GUZZETTI (IRPI-CNR Perugia) Zhengyu HU (Chinese Academy of Sciences) Piero GUILIZZONI (ISE-CNR) Luigi NASELLI-FLORES (University of Palermo) Daniel OLAGO (University of Nairobi) Ajit PATTNAIK (Chilika Development Authority) Richard ROBARTS (World Water and Climate Foundation) Adelina SANTOS-BORJA (Laguna Lake Development Authority) Juan SKINNER (Lake -

INSET Within Bhutan, 1996-1998 and the INSET Framework Within Bhutan, 2000 – 2004/6

INSET within Bhutan, 1996-1998 and the INSET Framework within Bhutan, 2000 – 2004/6. by DJ Laird TW Maxwell University of New England, Australia Wangpo Tenzin CAPSS, Education Division, RGoB & Sangay Jamtsho National Institute of Education, Bhutan INSET Project Report _________________________________________________________ i Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – INSET PROJECT 1996-1998 .................................................................. 1 Reconceptualisation of INSET ............................................................................................. 1 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 7 BACKGROUND TO THE INSET PROJECT ........................................................................................ 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Project Brief.......................................................................................................................... 8 Rationale for Project Involvement ........................................................................................ 8 Project Questions .................................................................................................................. 9 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK .......................................................................................................... 11 Growth of School Systems in Developing Countries -

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

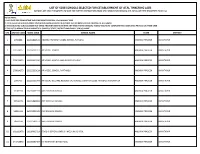

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

INTRODUCTION 1 1 Lepcha Is a Tibeto-Burman Language Spoken In

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 11 Lepcha is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Sikkim, Darjeeling district in West Bengal in India, in Ilm district in Nepal, and in a few villages of Samtsi district in south-western Bhutan. The tribal home- land of the Lepcha people is referred to as ne mayLe VÎa ne máyel lyáng ‘hidden paradise’ or ne mayLe malUX VÎa ne máyel málúk lyáng ‘land of eternal purity’. Most of the areas in which Lepcha is spoken today were once Sikkimese territory. The kingdom of Sikkim used to com- prise all of present-day Sikkim and most of Darjeeling district. Kalim- pong, now in Darjeeling district, used to be part of Bhutan, but was lost to the British and became ‘British Bhutan’ before being incorpo- rated into Darjeeling district. The Lepcha are believed to be the abo- riginal inhabitants of Sikkim. Today the Lepcha people constitute a minority of the population of modern Sikkim, which has been flooded by immigrants from Nepal. Although the Lepcha themselves estimate their number of speakers to be over 50,000, the total number is likely to be much smaller. Accord- ing to the 1991 Census of India, the most recent statistical profile for which the data have been disaggregated, the total number of mother tongue Lepcha speakers across the nation is 29,854. While their dis- tribution is largely in Sikkim and the northern districts of West Ben- gal, there are no reliable speaker numbers for these areas. In the Dar- jeeling district there are many Lepcha villages particularly in the area surrounding the small town of Kalimpong. -

The Land in Gorkhaland on the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India

The Land in Gorkhaland On the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India SARAH BESKY Department of Anthropology and Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, USA Abstract Darjeeling, a district in the Himalayan foothills of the Indian state of West Bengal, is a former colonial “hill station.” It is world famous both as a destination for mountain tour- ists and as the source of some of the world’s most expensive and sought-after tea. For deca- des, Darjeeling’s majority population of Indian-Nepalis, or Gorkhas, have struggled for sub- national autonomy over the district and for the establishment of a separate Indian state of “Gorkhaland” there. In this article, I draw on ethnographic fieldwork conducted amid the Gorkhaland agitation in Darjeeling’s tea plantations and bustling tourist town. In many ways, Darjeeling is what Val Plumwood calls a “shadow place.” Shadow places are sites of extraction, invisible to centers of political and economic power yet essential to the global cir- culation of capital. The existence of shadow places troubles the notion that belonging can be “singularized” to a particular location or landscape. Building on this idea, I examine the encounters of Gorkha tea plantation workers, students, and city dwellers with landslides, a crumbling colonial infrastructure, and urban wildlife. While many analyses of subnational movements in India characterize them as struggles for land, I argue that in sites of colonial and capitalist extraction like hill stations, these struggles with land are equally important. In Darjeeling, senses of place and belonging are “edge effects”:theunstable,emergentresults of encounters between materials, species, and economies. -

Minority Concentration District Project North Sikkim, Sikkim Sponsored By

Minority Concentration District Project North Sikkim, Sikkim Sponsored by the Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta R1, Baishnabghata Patuli Township Kolkata 700 094, INDIA. Tel.: (91) (33) 2462-7252, -5794, -5795 Fax: (91) (33) 24626183 E-mail: [email protected] Research Team Faculty: Prof. Partha Chatterjee, Dr. Pranab Kumar Das, Dr. Sohel Firdos, Dr. Saibal Kar, Dr. Surajit C. Mukhopadhyay, Prof. Sugata Marjit. Research Associate: Smt. Ruprekha Chowdhury. Research Assistants: Smt. Anindita Chakraborty, Shri Pallab Das, Shri Avik Sankar Moitra, Shri Ganesh Naskar and Shri Abhik Sarkar. Acknowledgment The research team at the CSSSC would like to thank Shri G. C. Manna, Deputy Director General, NSSO, Dr. Bandana Sen, Joint Director, NSSO, Shri S. T. Lepcha, Special Secretary, Shri P. K. Rai, Deputy Secretary, Social Justice, Empowerment and Welfare, Government of Sikkim, Shri T. N. Kazi, District Collector, Shri P. W. Lepcha, District Welfare Officer, Shri N. D. Gurung of the Department of Welfare of North Sikkim, and other department officials for their generous support and assistance in our work. 2 Content An Overview…………………………..….…………………...5 Significance of the Project……………………………………6 The Survey……...…………………………………………….8 Methodology…………………………………………………..9 Introducing Sikkim…………………………………………..10 North Sikkim………………………………………………….10 Demography………………………………………………….11 Selected Villages in Respective Blocks……………………..12 Findings……………………………………………………...13 1. Basic Amenities……………………………………..13 2. Education……………………………………………20 3. Occupation…………………………………………..30 4. Health………………………………………………..35 5. Infrastructure……………………………………….41 6. Awareness about Government Schemes……….….41 7. Other issues…………………………………………44 Recommendations…………………………………………...51 3 Appendices Table A1: General information………………………….….55 Table A2: Transport and Communication…………………55 Fig. A 1 Sources of Water………………………………..…..56 Fig. A2: Distance to Post-Office.……………………….……56 Fig. -

India’S Destiny

40317_u01.qxd 2/9/09 12:48 PM Page 1 one The Environment Thou art the ruler of the minds of all people, Thou Dispenser of India’s destiny. Thy name rouses the hearts Of the Punjab...Gujrat, and Maratha, Of Dravid, Orissa, and Bengal. It echoes in the hills of the Vindhyas and Himalayas, Mingles in the music of Jumna and Ganges, And is chanted by the waves of the Indian sea. from rabindranath tagore’s Jana Gana Mana (“The Mind of the Multitude of the People”), India’s national anthem india is the world’s most ancient civilization, yet one of its youngest nations. Much of the paradox found everywhere in India is a product of her inextricable antiquity and youth. Stability and dynamism, wisdom and folly, abstention and greed, patience and passion compete without end within the universe that is India. Everything is there, usually in magnified form. No ex- treme of lavish wealth or wretched poverty, no joy or misery, no beauty or horror is too wonderful, or too dreadful, for India. Nor is the passage to India ever an easy one for Western minds. Superficial similarities of language and outward appearances only compound confusion. For nothing is obviously true of India as a whole. Every generalization that follows could be disproved with evidence to the contrary from India itself. Nor is anything “Indian” ever quite as simple as it seems. Each reality is but a facet of India’s infinity of ex- perience, a thread drawn from the seamless sari of her history, a glimpse be- –s hind the many veils of her maya world of illusion. -

A Detailed Report on Implementation of Catchment Area Treatment Plan of Teesta Stage-V Hydro-Electric Power Project (510Mw) Sikkim

A DETAILED REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION OF CATCHMENT AREA TREATMEN PLAN OF TEESTA STAGE-V HYDRO-ELECTRIC POWER PROJECT (510MW) SIKKIM - 2007 FOREST, ENVIRONMENT & WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM GANGTOK A DETAILED REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION OF CATCHMENT AREA TREATMENT PLAN OF TEESTA STAGE-V HYDRO-ELECTRIC POWER PROJECT (510MW) SIKKIM FOREST, ENVIRONMENT & WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM GANGTOK BRIEF ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENT CONSERVATION OF TEESTA STAGE-V CATCHMENT. In the Eastern end of the mighty Himalayas flanked by Bhutan, Nepal and Tibet on its end lays a tiny enchanting state ‘Sikkim’. It nestles under the protective shadow of its guardian deity, the Mount Kanchendzonga. Sikkim has witnessed a tremendous development in the recent past year under the dynamic leadership of Honorable Chief Minister Dr.Pawan Chamling. Tourism and Power are the two thrust sectors which has prompted Sikkim further in the road of civilization. The establishment of National Hydro Project (NHPC) Stage-V at Dikchu itself speaks volume about an exemplary progress. Infact, an initiative to treat the land in North and East districts is yet another remarkable feather in its cap. The project Catchment Area Treatment (CAT) pertains to treat the lands by various means of action such as training of Jhoras, establishing nurseries and running a plantation drive. Catchment Area Treatment (CAT) was initially started in the year 2000-01 within a primary vision to control the landslides and to maintain an ecological equilibrium in the catchment areas with a gestation period of nine years. Forests, Environment & Wildlife Management Department, Government of Sikkim has been tasked with a responsibility of nodal agency to implement catchment area treatment programme by three circle of six divisions viz, Territorial, Social Forestry followed by Land Use & Environment Circle. -

The PLATEAU – North Sikkim

JAPANESE ALPINE NEWS 2013 ● HARISH KAPADIA THE PLATEAU Mountains of Sikkim – China Border This was my fifth visit to the mountains of Sikkim. As a young student I was part of the training course of the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in 1964. The mountains of west Sikkim, like Kabru, Rathong, Pandim and host of others were attractive to my young eyes. I returned in 1976. No sooner Sikkim became a state on India two us, Zerksis Boga and I obtained permits and roamed the valleys for more than a month in the northwest Sikkim, covering Zemu glacier, Lhonak valley Muguthang, Lugnak la, Sebu la and returned via the Lachung valley. I returned a few times to Darjeeling and Sikkim valleys visiting the Singalila ridge, lakes of lower Sikkim and surroundings of Gangtok and Kalimpong. If you stretch the area to the south, I made several visits to Darjeeling and nearby hills over the years. Moreover in Sikkim the approach to different valleys is so varied that it gives a feeling of trekking in different Himalayan zones. 1 High Himalayan Unknown Valleys, by Harish Kapadia, p.156. (Indus Books, New Delhi, 2001). Also Himalayan Journal, Vol.35, p.181 57 ● JAPANESE ALPINE NEWS 2013 In no other country on earth can one find such a variety of micro-climates within such a short distance as Sikkim, declared the eminent English botanist and explorer Joseph Hooker in his Himalayan Journals (1854), which documented his work collecting and classifying thousands of plants in the Himalaya in the mid-19th century. In the shadow of the Himalayas, by John Claude White, 1883 – 1908. -

The British Expedition to Sikkim of 1888: the Bhutanese Role

i i i i West Bohemian Historical Review VIII j 2018 j 2 The British Expedition to Sikkim of 1888: The Bhutanese Role Matteo Miele∗ In 1888, a British expedition in the southern Himalayas represented the first direct con- frontation between Tibet and a Western power. The expedition followed the encroach- ment and occupation, by Tibetan troops, of a portion of Sikkim territory, a country led by a Tibetan Buddhist monarchy that was however linked to Britain with the Treaty of Tumlong. This paper analyses the role of the Bhutanese during the 1888 Expedi- tion. Although the mediation put in place by Ugyen Wangchuck and his allies would not succeed because of the Tibetan refusal, the attempt remains important to under- stand the political and geopolitical space of Bhutan in the aftermath of the Battle of Changlimithang of 1885 and in the decades preceding the ascent to the throne of Ugyen Wangchuck. [Bhutan; Tibet; Sikkim; British Raj; United Kingdom; Ugyen Wangchuck; Thirteenth Dalai Lama] In1 1907, Ugyen Wangchuck2 was crowned king of Bhutan, first Druk Gyalpo.3 During the Younghusband Expedition of 1903–1904, the fu- ture sovereign had played the delicate role of mediator between ∗ Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, 46 Yoshida-shimoadachicho Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17F17306. The author is a JSPS International Research Fellow (Kokoro Research Center – Kyoto University). 2 O rgyan dbang phyug. In this paper it was preferred to adopt a phonetic transcrip- tion of Tibetan, Bhutanese and Sikkimese names. -

J J P B I English A188115 A188271 157 Girl's School 209 Dadabhai Nauroji Road Fort,Mumbai Pin Code :- 400001 Phone : 22612577 Additional Seatno

For HSC Board March Seating Plan/Centers CLICK HERE MAHARASHTRA STATE BOARD OF SECONDARY AND HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION, MUMBAI DIVISIONAL BOARD ,VASHI, NAVI MUMBAI 400 703. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SEATING ARRANGEMENT OF MARCH - 2014 S.S.C. EXAMINATION PAGE NO: 1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NAME OF THE CENTRE : -MUMBAI CST (FORT) CENTRE NO :- 2001 FROM :- A187165 TO A188271 REGISTER NO OF CANDIDATES :- 1107 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SR SCHOOL NAME OF THE PLACE NUMBER OF CANDIDATES NO IND NO TELEPHONE NO FROM TO TOTAL -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 3101004 SIR J J FORT BOYS HIGH SCHOOL A187165 A187364 200 209 DR DADABHAI NAUROJI ROAD FORT MAIN CENTRE MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22626155 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- 2 3101011 BHARDA NEW HIGH SCHOOL A187365 A187764 400 HAZARIMAL SOMANI MARG FORT MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22072349 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- 3 3101033 ST ANNIES HIGH SCHOOL A187765 A188114 350 MADAM KAMA ROAD FORT MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22020733 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- 4 3101005 SIRwww.Exam2014.in J J P B I ENGLISH A188115 A188271 157 GIRL'S SCHOOL 209 DADABHAI NAUROJI ROAD FORT,MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22612577 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- For HSC Board March Seating Plan/Centers CLICK HERE -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SEATING ARRANGEMENT OF MARCH - 2014